Relationships between

organizational support, customer

orientation, and work outcomes

A study of frontline bank employees

Ugur Yavas

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee, USA, and

Emin Babakus

The University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, USA

Abstract

Purpose– This paper seeks to examine the nature of relationships between six organizational support mechanisms, a personal resource, and selected psychological and behavioral work outcomes. A related objective of the study is to uncover whether these relationships exhibit similar patterns between employees with different characteristics.

Design/methodology/approach– Data for the study were collected from the employees of a large bank in New Zealand. Usable responses were obtained from 530 employees.

Findings– Results show that supervisory support is most closely associated with psychological work outcomes. On the other hand, job performance is more susceptible to influences of service technology and empowerment. Also customer orientation, as a personal resource, impacts job performance.

Research limitations/implications– Using multiple-informants (e.g. measuring frontline employees’ job performance on the basis of their supervisors’ or customers’ assessments) would help minimize common-method variance. To cross-validate our results, replication studies among other samples of frontline employees in banking as well as other service settings are in order.

Practical implications– To fuel greater affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction among frontline employees and to reduce their turnover intentions, management must take proactive actions for the frontline employees to receive support and encouragement from their supervisors. Instituting a structured mentoring program and providing training programs to supervisors in support skills can also pay dividends.

Originality/value– The study shows that an undifferentiated approach is warranted in managing employees. Similar strategies would be equally effective in inducing favorable and reducing negative affective and performance outcomes among employees with different demographic characteristics.

KeywordsBanking, Employees, Customer orientation, Business support services, New Zealand

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

Regulatory, structural and technological factors have significantly changed the

banking environment throughout the world (Anguret al., 1999). In a milieu becoming

increasingly competitive, bank executives realize that creating and maintaining a loyal

customer base is a key to their survival and success (see Yavas et al., 1997).

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0265-2323.htm

IJBM

28,3

222

Received October 2009 Accepted December 2009

International Journal of Bank Marketing

Vol. 28 No. 3, 2010 pp. 222-238

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited 0265-2323

Accordingly, they design multi-pronged strategies to deliver quality service to customers and enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty. Such executives also recognize that no strategy aimed at satisfaction and retention of external customers can be considered complete unless it includes programs for reaching and winning over internal customers (Schneider and White, 2004). Viewed particularly important in this context are the frontline employees who, because of their boundary-spanning roles, play a crucial role in service delivery and building relationships with customers (Babakuset al., 2003). Being direct participants in implementing the marketing concept

(Brownet al., 2002), frontline employees’ attitudes and behaviors towards customers

determine customers’ perceived service quality, satisfaction and emotional

commitment to an organization (Henning-Thurau, 2004; Yoonet al., 2001). Frontline

employees also have the capability, more so than other employees in an organization, for returning aggrieved customers to a state of satisfaction after a service failure occurs (Yavaset al., 2004).

Not surprisingly, bank executives view retention of motivated, satisfied and committed frontline employees as important to business success as customer satisfaction and retention (see Yavaset al., 1997). A question that begs an answer is: what support mechanisms and resources induce positive and reduce negative work outcomes among frontline bank employees? In this study, we seek an answer to this decidedly critical question. Specifically, we investigate the nature of relationships between several organizational support factors and a personal resource, and selected psychological and behavioral work outcomes. A related objective of our study is to uncover whether these relationships exhibit similar patterns between employees with different characteristics. We use frontline bank employees in New Zealand as our study setting.

A study addressing these issues is relevant and significant for several reasons. First, while some studies in the past have examined the relationships between organizational support and work outcomes among frontline employees in other service sectors (Bakkeret al., 2004; Demeroutiet al., 2001) and other countries (e.g. Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004), there is a paucity of research addressing this topic in the context of banking in general and New Zealand in particular. Second, previous studies have been limited in terms of the number of resources and/or outcomes they include in their conceptualization and scope. In this study, we use a comprehensive list of seven antecedent (six organizational support resources and a personal resource) and four work outcome (three psychological outcomes and a behavioral outcome) variables and investigate their interrelationships. Third, the findings from the study can provide bank executives in New Zealand with valuable insights in ways of enhancing positive and reducing negative work outcomes of their frontline

employees. Furthermore, an understanding of the role of background

characteristics is vital to managers in determining if, for instance, an undifferentiated or a differentiated (e.g. gender-specific) approach is warranted in

managing frontline employees (Alexandrovet al., 2007).

In the next section we present the relevant literature. This is followed by discussions of the method and results of our empirical study. We conclude with implications of the results and suggestions for future research.

A study of

frontline bank

employees

Relevant literature Organizational support

Inspired by the works of Bakkeret al.(2004), Halbesleben and Buckley (2004), and

Lytle et al. (1998), we define organizational support as a set of enduring policies,

practices, procedures and tools that:

. diminish the demands of the job; and/or

. assist employees in achieving their work goals and stimulate their personal

growth/development.

Such support may be physical, psychological or social in nature and may be located at the organizational and task levels, in interpersonal/social relations and the organization of work. Organizational support can be in the forms of performance feedback, skill variety, autonomy, job security, training, salary, supervisory support, empowerment, team climate, rewards, career opportunities, servant leadership and

service technology support (Babakuset al., 2003; Bakker, Demerouti, Taris, Schaufeli

and Schreurs, 2003; Baker, Demerouti, de Boer and Schaufeli 2003; Ben-Zur and Yagil, 2005; Demeroutiet al., 2001; Lewig and Dollard, 2003; Lytleet al., 1998; Maslach, 2005; Wilk and Moynihan, 2005). In our study, we focus on six organizational resources that are widely recognized as being crucial to organizational success and outcomes. They are supervisory support, training, servant leadership, rewards, empowerment and service technology support (Babakuset al., 2003; Demeroutiet al., 2001; Lytleet al., 1998).

Supervisory support (Bell et al., 2004; Babin and Boles, 1996) refers to the

willingness of the supervisors to go to bat for their subordinates. It manifests itself in the encouragement and concern supervisors provide to their subordinates. According to the reciprocity rule as employees receive greater support from their supervisors, their sense of obligation to reciprocate with greater effort increases.

Training programs sponsored by an organization can improve employees’ task-related and behavioral skills, enhance their capability to deal with varying customer needs, personalities and circumstances effectively. Employees who receive training become more capable and motivated, and provide higher levels of service. In contrast, employees who do not possess the requisite job and interpersonal skills fail to provide satisfactory service and cannot deal with customer demands and complaints effectively (Boshoff and Allen, 2000). Training not only helps develop skills and creative thinking necessary to serve customers effectively, but also sends a strong signal to frontline employees regarding top management’s commitment to service

quality (Babakus et al., 2003). Servant leadership (Lytle et al., 1998) reflects the

managerial service behaviors, which conspicuously direct and shape the service climate in an organization through example rather than simply dictating service policies.

Rewards characterize inducements employees receive from their organization, including compensation, esteem, status and social identity. Particularly monetary rewards count a lot in frontline service jobs, which are generally low paying positions

(Babakus et al., 2003; Forrester, 2000). Having appropriate reward policies in place

induces frontline employees to deliver high quality services to customers and to deal with customer complaints effectively (see Lytleet al., 1998). On the other hand, lack of rewards creates an unpleasant environment and diminishes employees’ work efforts and/or may cause them to withdraw from the job.

IJBM

28,3

Empowerment refers to the freedom and ability to make decisions and commitments (Forrester, 2000). It entails a set of managerial activities and practices, which provide employees with power, authority and control, and involves transmission of power to those who are less powerful in an organization (Ergeneli

et al., 2007). Empowerment enhances employees’ problem solving capability and helps them to reach their full potential. Empowered employees have the responsibility and

authority to act quickly without a long chain of command (see Babakuset al., 2003).

Service technology support encompasses provision of sophisticated and integrated tools to employees (Lytleet al., 1998). Such support enables frontline employees to be free from routine tasks and gives them more time to deal with customers. Technology can elevate the competitive advantage of a service organization by enhancing employees’ capacity to offer superior service to their customers.

Customer orientation as a personal resource

Customer orientation, which has been studied both at the organizational and individual

worker levels, is one of marketing’s most celebrated concepts (see Deshpandeet al.,

1993; Donavanet al., 2004; Henning-Thurau, 2004; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Narver

and Slater, 1990). At the organizational level, customer orientation is an integral

component of a market orientation (Deshpandeet al., 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990),

which provides a unifying focus for the activities of an organization and serves as a vehicle for the implementation of the time-honored marketing concept as a business philosophy (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). A firm’s customer orientation is not only a potent path to business success, but also results in desirable employee outcomes (Henning-Thurau, 2004; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993).

At the individual level, customer orientation describes a personal resource of an employee and is defined as “an employee’s tendency or predisposition to meet

customer needs in an on-the-job context” (Brown et al., 2002, p. 111). Customer

orientation, as a personal resource, may serve as an antidote to the detrimental effects of job demands and can lead to delivery of superior customer service, especially when combined with organizational support. Among others, customer-oriented employees exhibit strong concern for others’ needs, optimism and cheerfulness. They also show low levels of nervousness and frustration during service encounters. Customer orientation makes employees more capable of “serving with a smile”, with less “emotional labor” or “acting” (see Grandey, 2003).

Perhaps more importantly, customer orientation positively influences an employee’s

job satisfaction and commitment (Donavanet al., 2004). In this study, we draw on the

conceptualization of customer orientation at the individual worker level (Brownet al., 2002) and treat it as a personal resource.

Work outcomes

In various contextual settings, research in marketing and management has focused on a number of work outcomes ranging from affective organizational commitment to turnover intentions to job performance (e.g. Donavanet al., 2004; Ogaard, 2006; Yavas

et al., 2008). As discussed by Rhoadset al.(1994) and Singhet al.(1996), these outcomes can be dichotomized into psychological (e.g. job satisfaction, tension) and behavioral outcomes (e.g. turnover, job performance). Psychological outcomes reflect employees’ psychological approach or avoidance attitudes toward their jobs while behavioral outcomes reflect employees’ performance results. In our study, we focus on three

A study of

frontline bank

employees

psychological (affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover

intentions) and a behavioral outcome ( job performance). Under Rhoadset al.’s (1994)

and Singhet al.’s (1996) taxonomy, turnover intentions represent the avoidance aspect of psychological outcomes. Turnover intentions, in turn, are recognized as precursors

to actual turnover (e.g. Allen et al., 2003; Jackofsky, 1984), which is a behavioral

outcome (Rhoadset al., 1994).

Affective organizational commitment refers to an attitude in the form of an attachment between an individual and his/her organization. It is reflected in the relative strength of an individual’s psychological identification and involvement with the organization (Mowdayet al., 1979). Job satisfaction reflects a positive affective state resulting from an employee’s overall assessment (i.e. not any specific aspect(s)) of

his/her job (Babin and Boles, 1998; Singh et al., 1996). Performance refers to an

employee’s assessment of his/her performance relative to his/her peers on job-related

behaviors and results (Babin and Boles, 1998; Singh et al., 1996). Finally, turnover

intentions reflect employees’ thoughts about quitting the organization they work for (Singhet al., 1996).

Past research, albeit not simultaneously using all the independent and dependent variables we include here, demonstrates that organizational support and work outcomes are related. Research, for instance, reveals that supervisory support leads employees to exert more effort in the workplace (Brown and Peterson, 1994; Den Hartog and Verburg, 2002; Schneider and Bowen, 1993), enhances employees’ positive attitudes toward their work and reduces their turnover intentions (Babin and Boles, 1996; Bellet al., 2004; Ito and Brotheridge, 2005). Training programs in task-related and behavioral skills enhance employees’ affective commitment to their organization (Tsui

et al., 1997) and reduce their turnover intentions (Cheng and Brown, 1998). Empowered employees exhibit lower turnover intentions (Bowen and Lawler, 1992). Likewise, an organization’s reward structure has a significant impact on employee loyalty and commitment (Lawler, 2000). Rewards reduce employees’ turnover intentions as well (Podsakoffet al., 2006).

Prior research also reveals that the variables within our dependent variable set may also be interrelated. For instance a meta-analysis ( Jaramilloet al., 2005) shows that there is a significant relationship between organizational commitment and job performance. Job satisfaction as well demonstrates a significant relationship with job performance (Babakuset al., 2003). Both job satisfaction and affective organizational

commitment depict negative relationships with turnover intentions (Alexandrovet al.,

2007). While the research is not monotonic in support, the weight of the evidence also suggests that job performance and turnover intentions are related ( Jackofsky, 1984).

Method Sample

To achieve the purposes of the study, data were collected from boundary-spanning employees of a large bank in New Zealand who spent their time dealing directly with customers for transactions and/or responding to customer queries, problems and complaints. Specifically, 724 questionnaires were distributed to employees working in 50 branches of the bank via the bank’s intranet. The manager of each bank wrote a memo to the employees and requested their cooperation. Employees were given assurance of confidentiality and allowed to respond to the survey anonymously during work hours. The responses were transferred into a data file at the corporate office

IJBM

28,3

under the supervision of a member of the research team. By the cutoff date for data collection, 530 usable surveys were received for a response rate of 73.2 percent. The number of responses across the bank branches ranged from five to 27 with an average of 10.6 responses per branch.

Over three-quarters of the respondents (76.2 percent) were female. In total, 58 percent had secondary education and 31.4 percent had college/university education or more. Respondents were spread across all age groups with 20.7 percent between the ages of 18 and 24, 25.8 percent between the ages of 25 and 34, 22.6 percent between the ages of 35 and 44, 18.7 percent between the ages of 45 and 54 and 12.2 percent 55 years and older. A comparison of the sample profile to the company records indicated that the sample was representative of the population of frontline employees.

Measurement

Dependent variables.Affective organizational commitment was operationalized via six

items from Mowdayet al.(1979). Six items each adapted from Babin and Boles (1998)

were used to measure job satisfaction and performance. Turnover intentions, was

measured with four items adapted from Singhet al. (1996) and Boshoff and Allen

(2000). Responses to each of these items were elicited on five-point scales ranging from

5 ¼strongly agree to 1 ¼strongly disagree. Statements were scored in such a way

that higher scores indicated higher levels of affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job performance and turnover intentions.

Independent variables. Three items from Bellet al. (2004) were used to measure supervisory support. A four-item scale was used to measure training (Rogget al., 2001). Servant leadership (six items) and empowerment (two items) were measured with

items adapted from Lytleet al. (1998). Service technology support (four items) and

rewards (three items) were measured using items adapted from Lytleet al.(1998) and

Johnson (1996).

Customer orientation was measured via 13 items from Donavan et al. (2004).

Responses to each of these items were also obtained on five-point scales ranging from

5 ¼strongly agree to 1 ¼strongly disagree. Again because of the scoring system

used, higher scores indicated higher levels of supervisory support, training, servant leadership, rewards, empowerment, service-technology support and customer orientation. Age and education were measured using five-point scales with higher scores indicating older age and higher education. During the analysis stage, these variables were reduced to a binary (0/1) form (see the Appendix). Gender was recorded

as 1 ¼female and 0 ¼male.

In designing the questionnaire, items comprising the perceptual dependent and independent variables were separated in an effort to reduce single-source method bias (Podsakoffet al., 2003). As shown previously, the internal consistency reliabilities of

the measures with the exception of the rewards measure (a¼ 0.62) exceeded the

recommended minimum threshold value of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). Prior to administering in the field, the questionnaire was pre-tested with a pilot sample of 25 employees and no changes in the wording of the questions were deemed necessary.

Results

Canonical correlation analysis was employed to examine the relationships between the independent and the dependent variables described in the preceding section. This technique is particularly useful in situations where, as is the case here, there are

A study of

frontline bank

employees

multiple dependent variables and correlations exist between and within variable sets

(Hair et al., 1998). The simplest way to view canonical analysis is as a kind of

double-barreled principle components analysis. Given a correlation matrix representing the between and within correlations of two sets of variables, the analysis derives successive pairs of linear functions of independent and dependent variable sets. The functions are maximally correlated between the variable sets while mutually uncorrelated within the sets. The first pair of canonical functions extracts the maximum variance possible, the second pair extracts the maximum variance not accounted for by the first pair and successive canonical functions are extracted in the same fashion.

In canonical correlation analysis, the maximum number of canonical functions that can be extracted from the independent and the dependent variable sets equals the number of variables in the smaller set. Since the smaller set in the present study (i.e. the dependent set) consists of four variables, a maximum of four canonical functions can be extracted. As in principal components analysis, the objective of canonical analysis is to summarize the complex multivariate relationship between the two sets of variables in a smaller number of canonical variates (linear composites or combinations) without too much loss of information. Considering the criteria (i.e. statistical significance of the function and the magnitude of the canonical correlations depicting the bivariate correlations between the independent and the dependent linear composites)

recommended by Hair et al. (1998), in this study two canonical functions were

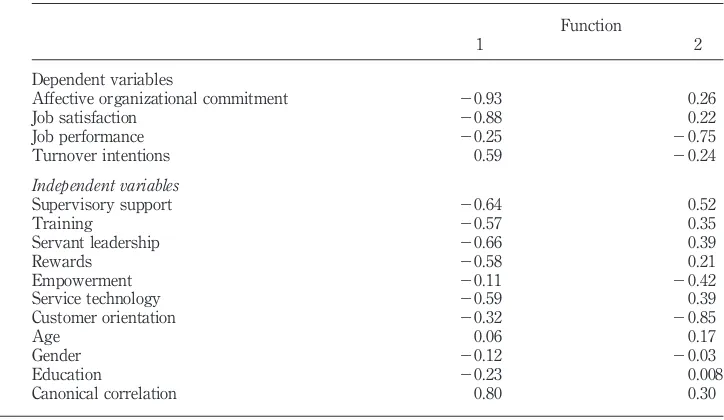

retained. Both functions were significant (Function 1: F¼ 16.48, p,0:0001 and

Function 2: F¼ 2.41, p,0:001). As shown in Table I, the canonical correlations

between the dependent and independent variates of the first and the second functions were 0.80 and 0.30 respectively.

In interpreting the underlying structures of the independent and the dependent variable composites, canonical loadings can be used. Also referred to as structure

Function

1 2

Dependent variables

Affective organizational commitment 20.93 0.26

Job satisfaction 20.88 0.22

Job performance 20.25 20.75

Turnover intentions 0.59 20.24

Independent variables

Supervisory support 20.64 0.52

Training 20.57 0.35

Servant leadership 20.66 0.39

Rewards 20.58 0.21

Empowerment 20.11 20.42

Service technology 20.59 0.39

Customer orientation 20.32 20.85

Age 0.06 0.17

Gender 20.12 20.03

Education 20.23 0.008

Canonical correlation 0.80 0.30

Table I.

Canonical loadings

IJBM

28,3

correlations, loadings measure the simple linear correlations between an original observed variable in the independent (or dependent) set and the set’s canonical variate. As can be seen from the loadings presented in Table I, the first dependent variate was characterized by affective organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. On the other hand, job performance was at the root of the dependent variate of the second function. An inspection of the loadings of the independent variables revealed that gender and education were more closely associated with the first independent variate. The second independent variate, on the other hand, depicted closer association with age. Customer orientation and empowerment also had high loadings on this variate.

Having determined the underlying structures of the variates, in the next phase of analysis, an attempt was made to obtain insights into which independent variables had the most influence in relation to the dependent variable composites (i.e. variates). The standardized canonical coefficients, which are analogous to standardized beta coefficients in multiple regression, and the weights we calculated based on these coefficients revealed some interesting results. As shown in Table II, supervisory support had the most impact on the first dependent variate (i.e. affective outcomes). A close scrutiny of the results revealed that the second dependent variate (i.e. job performance) was most susceptible to influences of customer orientation followed by service technology and empowerment. Overall, the background characteristics did not have much impact on the dependent variates and collectively accounted for 10 percent of the weight in each case. Furthermore, their relative impacts on the dependent variates were comparable.

Discussion

Several inferences surface from our results. First, our findings demonstrate that earlier findings based on studies conducted in other service sectors and countries can be extended to banking and New Zealand. Second, our results show that different forms of

Function

n1 relative weights n2 relative weights

Dependent variables

Affective organizational commitment 20.58 0.38 0.49 0.24

Job satisfaction 20.53 0.35 0.33 0.16

Job performance 20.30 0.20 21.17 0.57

Turnover intentions 20.11 0.07 0.07 0.03

Independent variables

Supervisory support 20.77 0.42 0.27 0.11

Training 20.14 0.08 0.07 0.03

Servant leadership 0.04 0.02 0.02 0.01

Rewards 20.03 0.01 20.25 0.10

Empowerment 20.16 0.09 20.47 0.19

Service technology 20.22 0.12 0.48 0.20

Customer orientation 20.29 0.16 20.61 0.25

Age 0.11 0.06 0.10 0.04

Gender 0.02 0.01 0.06 0.02

Education 0.06 0.03 0.12 0.05

organizational support are associated with different work outcomes. For instance, the results suggest that supervisory support is most closely associated with affective work outcomes. On the other hand, job performance is more likely to be impacted by service technology and empowerment. Third, our results also confirm that work outcomes can be dichotomized into psychological (organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions) and behavioral outcome ( job performance) categories as discussed

by Rhoadset al.(1994) and Singhet al.(1996). Fourth, however, these work outcomes

do not seem to show any variations across employee characteristics.

Finally, an intriguing result of our study is the impact of customer orientation (a personal resource) on job performance more so than psychological outcomes. Some plausible explanations can be offered for this finding. Customer orientation encompasses an internal drive to engage in such customer-satisfying behaviors as finding and promptly delivering solutions to customer problems, being well-prepared and organized during customer interactions, approaching customers with natural ease and confidence, treating customers with both kindness and politeness, maintaining a consistent level of emotionality during customer interactions and a natural propensity to enjoy work (see Cran, 1994; Donavanet al., 2004; Gwinneret al., 2005; Surprenant and Solomon, 1987). Also agreeableness, a basic personality trait, which reflects cooperation and service to others, is at the root of customer orientation (Brownet al.,

2002; Licataet al., 2003). Customer-oriented frontline employees perform well in the

workplace as they are predisposed to enjoying the work of serving customers (Brown

et al., 2002; Donavanet al., 2004).

In addition, it may be surmised that, customer orientation may actually serve as an antidote to job demands and play an instrumental role in increasing job resources. For instance, when a frontline employee lacks adequate information and procedures to accomplish a required task, customer orientation may serve as internal compass and provide clear, well-defined guidelines to reduce uncertainties and ambiguities inherent in that task ( Joneset al., 2003). Also, customer orientation may alleviate the negative effects of conflicts in a job environment as it enables employees to control a threatening

situation with calm and emotional stability (Donavan et al., 2004; Surprenant and

Solomon, 1987; Winstead, 2000). Furthermore, customer orientation may lead employees to find more effective and creative ways of serving customers, which may actually reduce work overload. Similarly, customer orientation may encourage employees to seek more resources from management to better serve customers. All of these factors may explain the strong impact of customer orientation on job performance.

Managerial implications

Perhaps the most important managerial implication emerging from this study is that an undifferentiated approach would pay dividends in managing employees. In other words, similar strategies would be equally effective in inducing favorable and reducing negative affective and performance outcomes among employees with different demographic characteristics. Results of the study suggest that to fuel greater affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction among frontline employees and to reduce their turnover intentions, management must take proactive actions for the frontline employees to receive support and encouragement from their supervisors. In this context, actions such as instituting a structured mentoring program and providing training programs to supervisors in support skills, for instance, can pay dividends.

IJBM

28,3

Support given to subordinates should not be limited to emotional support but should also include informational support. When employees’ beliefs in their supervisors’ reliability, dependability, competence and willingness to help subordinates increases as a result of mentoring programs, then, among others, subordinates’ job satisfaction would improve and their withdrawal tendencies from their jobs would diminish.

Likewise, to improve employee performance, employees must be empowered. In empowering employees, giving them more power and authority should not be the only goal. In addition, employees’ psychological empowerment should be enhanced. Psychological empowerment reflects whether or not employees perceive themselves as

being empowered. As Ergeneliet al. (2007) discuss, if employees do not behave as

expected when power and control are transferred to them, this may be due to lack of awareness of the fact that they are empowered. Also given the study results, employees must be provided with requisite service technologies to further enhance their performance.

Finally, the linkage between customer orientation and job performance leads to an interesting managerial implication. Customer orientation entails such personality traits as enjoying serving others, being caring and calm, and showing emotional stability in stressful situations. All of these traits are particularly fitting for frontline service jobs. Given that a good fit between a person’s abilities and personality and the requirements

of a job leads to better job outcomes (see Donavanet al., 2004), management should

recruit and select frontline employees who possess customer orientation qualities. This would necessitate incorporating predictors of customer orientation into the service worker selection process. Also management should consider making customer orientation an explicit component of periodic employee evaluations to align its broader policies to nourish and nurture employees’ customer orientation over the long run.

It should be remembered that as discussed in Schneider and White’s (2004) the

“customer-linkage” model and more specifically in Heskett et al.’s (1994) the

“service-profit chain” model, any managerial actions to improve employees’ affective and performance job outcomes would lead not only to better customer outcomes (e.g. customer loyalty, customer satisfaction) but also stimulate such desirable organizational outcomes as profits and growth.

Limitations and future research directions

Although this study contributes to our knowledge base, viable prospects for further research remain. First, the constructs in this study were developed by responses from the same participants. This may potentially provide biased estimates of model parameters. To avoid the problem in future studies, multiple sources should be used in data collection and, for instance, job performance should be measured via responses from supervisors and/or customers. Second, in this study we used frontline employees of a single company in a single country in a single industry and at a single point in time. This may have led to sampling artifacts and ignored the potential temporal dynamics of the relationships. Therefore, generalizations beyond the specific context of this research must be guarded. Replications in New Zealand and elsewhere among frontline employees in banking as well as other service settings are in order for conclusive generalizations. Likewise, longitudinal designs would help determine the causal relationships among the study variables. Third, our focus in this study was on the individual frontline employee as the unit of analysis and we did not differentiate between employees of small vs. large branches. Possible psychological climate and

A study of

frontline bank

employees

management style variances emanating from the size of a branch may have confounded the results. Hence, investigation of the impact of branch size on the relationships studied here is a worthy topic for future research.

References

Alexandrov, A., Babakus, E. and Yavas, U. (2007), “The effects of perceived management concern for frontline employees and customers on turnover intentions: moderating role of employment status”,Journal of Service Research, Vol. 9 No. 4, pp. 356-71.

Allen, D.G., Shore, L.M. and Griffeth, R.W. (2003), “The role of perceived organizational support and supportive human resource practices in the turnover process”, Journal of Management, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 99-118.

Angur, M.G., Nataraajan, R. and Jahera, J.S. (1999), “Service quality in the banking industry: an assessment in a developing economy”,International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 116-23.

Babakus, E., Yavas, U., Karatepe, O. and Avci, T. (2003), “The effect of management commitment to service quality on employees’ affective and performance outcomes”,Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 272-86.

Babin, B.J. and Boles, J.S. (1996), “The effects of perceived co-worker involvement and supervisor support on service provider role stress, performance and job satisfaction”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 72 No. 1, pp. 57-75.

Babin, B.J. and Boles, J.S. (1998), “Employee behavior in a service environment: a model and test of potential differences between men and women”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62 No. 2, pp. 77-91.

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E. and Verbeke, W. (2004), “Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 83-104.

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., de Boer, E. and Schaufeli, W.B. (2003), “Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 62 No. 2, pp. 341-56.

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T.W., Schaufeli, W.B. and Schreurs, P.J.G. (2003), “A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations”,International Journal of Stress Management, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 16-38. Bell, S.J., Menguc, B. and Stefani, S.L. (2004), “When customers disappoint: a model of relational

internal marketing and customer complaints”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 112-26.

Ben-Zur, H. and Yagil, D. (2005), “The relationship between empowerment, aggressive behaviors of customers, coping, and burnout”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 81-99.

Boshoff, C. and Allen, J. (2000), “The ınfluence of selected antecedents on frontline staff’s perceptions of service recovery performance”,International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 63-90.

Bowen, D.E. and Lawler, E.E. (1992), “The empowerment of service workers: what, why, how, and when”,Sloan Management Review, Vol. 33, Spring, pp. 31-9.

Brown, S.P. and Peterson, R.A. (1994), “The effect of effort on sales performance and job satisfaction”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58 No. 2, pp. 70-80.

IJBM

28,3

Brown, T.J., Mowen, J.C., Donavan, T. and Licata, J.W. (2002), “The customer orientation of service workers: personality trait determinants and effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings”,Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 39, February, pp. 110-9. Cheng, A. and Brown, A. (1998), “HRM strategies and labor turnover in the hotel industry:

a comparative study of Australia and Singapore”,The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 136-54.

Cran, D.J. (1994), “Towards validation of the service orientation construct”,The Services Industry Journal, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 34-44.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Nachreiner, F. and Schaufeli, W.B. (2001), “The job demands-resources model of burnout”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86 No. 3, pp. 499-512.

Den Hartog, D.N. and Verburg, R.M. (2002), “Service excellence from the employees’ point of view: the first line supervisors”,Managing Service Quality, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 159-64. Deshpande, R., Farley, J.U. and Webster, F.E. Jr (1993), “Corporate culture, customer orientation,

and innovativeness in Japanese firms: a quadrad analysis”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57, pp. 23-37.

Donavan, D.T., Brown, T.J. and Mowen, J.C. (2004), “Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors”,

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 128-46.

Ergeneli, A., Ari, G.S. and Metin, S. (2007), “Psychological empowerment and its relationship to trust in immediate managers”,Journal of Business Research, Vol. 60 No. 1, pp. 41-9. Forrester, R. (2000), “Empowerment: rejuvenating a potent idea”, Academy of Management

Executive, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 67-80.

Grandey, A.A. (2003), “When ‘the show must go on’: surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 46 No. 1, pp. 86-96.

Gwinner, K., Bitner, J., Brown, S.W. and Kumar, A. (2005), “Service customization through employee adaptiveness”,Journal of Service Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 131-48.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. and Black, W.C. (1998),Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Halbesleben, J.R.B. and Buckley, M.R. (2004), “Burnout in organizational life”, Journal of Management, Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 859-79.

Henning-Thurau, T. (2004), “Customer orientation of service employees: its impact on customer satisfaction, commitment, and retention”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 460-78.

Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E. and Schlesinger, L.A. (1994), “Putting the service-profit chain to work”,Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72, March-April, pp. 164-74. Ito, J.K. and Brotheridge, C.M. (2005), “Does supporting employees’ career adaptability lead to commitment, turnover, or both?”,Human Resource Management, Vol. 44 No. 1, pp. 5-19. Jackofsky, E.F. (1984), “Turnover and job performance: an integrated process model”,Academy

of Management Review, Vol. 9, January, pp. 74-83.

Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J.P. and Marshall, G.M. (2005), “A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and salesperson job performance: 25 years of research”,

Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58, June, pp. 705-14.

Jaworski, B.J. and Kohli, A.K. (1993), “Market orientation: antecedents and consequences”,

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 57, July, pp. 53-70.

A study of

frontline bank

employees

Johnson, J.W. (1996), “Linking employee perceptions of service climate to customer satisfaction”,

Personnel Psychology, Vol. 49 No. 4, pp. 831-51.

Jones, E., Busch, P. and Dacin, P. (2003), “Firm market orientation and salesperson customer orientation: interpersonal and intrapersonal influences on customer service and retention in business-to-business buyer-seller relationships”,Journal of Business Research, Vol. 56 No. 4, pp. 323-40.

Kohli, A.K. and Jaworski, B.J. (1990), “Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, April, pp. 1-18.

Lawler, E.E. (2000),Rewarding Excellence, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Lewig, K.A. and Dollard, M.F. (2003), “Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in call center workers”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 366-92.

Licata, J.W., Mowen, J.C., Harris, E.G. and Brown, T.J. (2003), “On the trait antecedents and outcomes of service worker job resourcefulness: a hierarchical model approach”,Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 256-71.

Lytle, R.S., Hom, P.W. and Mokwa, M.P. (1998), “SERV*OR: a managerial measure of organizational service-orientation”,Journal of Retailing, Vol. 74 No. 4, pp. 455-89. Maslach, C. (2005), “Understanding burnout: work and family issues”, in Halpern, D.F. (Ed.),

From Work-family Balance to Work-family Interaction: Changing the Metaphor, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 99-114.

Mowday, R.T., Steers, R.M. and Porter, L.W. (1979), “The measurement of organizational commitment”,Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 224-47.

Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. (1990), “The effects of a market orientation on business profitability”,

Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, October, pp. 20-35.

Nunnally, J.C. (1978),Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Ogaard, T. (2006), “Do organizational practices matter for hotel industry employees’ jobs: a study of organizational practice archetypal configurations and job outcomes”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 647-61.

Podsakoff, P.M., Bommer, W.H., Podsakoff, N.P. and MacKenzie, S.B. (2006), “Relationships between leader reward and punishment behavior and subordinate attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors: a meta-analytic review of existing and new research”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 99 No. 2, pp. 113-42.

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2003), “Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies”,

Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 879-903.

Rhoads, G.K., Singh, J. and Goodel, P.G. (1994), “The multiple dimensions of role ambiguity and their impact on psychological and behavioral outcomes of industrial salespeople”,Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 1-24.

Rogg, K.L., Schmidt, D.B., Shull, C. and Schmitt, N. (2001), “Human resource practices, organizational climate, and customer satisfaction”,Journal of Management, Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 431-49.

Schaufeli, W.B. and Bakker, A.B. (2004), “Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 293-315.

Schneider, B. and Bowen, D.E. (1993), “The service organization: human resources management is crucial”,Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 39-52.

IJBM

28,3

Schneider, B. and White, S.S. (2004),Service Quality: Research Perspectives, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Singh, J., Goolsby, J.R. and Rhoads, G.K. (1996), “Behavioral and psychological consequences of boundary spanning burnout for customer service representatives”,Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 31, November, pp. 558-69.

Singh, J., Verbeke, W. and Rhoads, G.K. (1996), “Do organizational practices matter in role stress processes? A study of direct and moderating effects of marketing-oriented boundary spanners”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 No. 3, pp. 69-86.

Surprenant, C.F. and Solomon, M.R. (1987), “Predictability and personalization in the service encounter”,Journal of Marketing, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 86-96.

Tsui, A.S., Pearce, J., Porter, L.W. and Tripoli, A.M. (1997), “Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: does investment in employee pay off?”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40 No. 5, pp. 1089-121.

Wilk, S.L. and Moynihan, L.M. (2005), “Display rule ‘regulators’: the relationship between supervisors and worker emotional exhaustion”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 90 No. 5, pp. 917-27.

Winstead, K.F. (2000), “Service behaviors that lead to satisfied customers”,European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 34 Nos 3/4, pp. 399-417.

Yavas, U., Babakus, E. and Karatepe, O.M. (2008), “Attitudinal and behavioral consequences of work-family conflict and family-work conflict: does gender matter?”,International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 7-31.

Yavas, U., Bilgin, Z. and Shemwell, D.J. (1997), “Service quality in the banking sector in an emerging economy: a consumer survey”,International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 6, pp. 217-23.

Yavas, U., Karatepe, O.M., Babakus, E. and Avci, T. (2004), “Customer complaints and organizational responses: a study of hotel guests in Northern Cyprus”, Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing, Vol. 11 Nos 2/3, pp. 31-46.

Yoon, M., Beatty, S. and Suh, J. (2001), “The effect of work climate on critical employee and customer outcomes: an employee-level analysis”,International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 12 No. 5, pp. 500-21.

Further reading

Kickul, J. and Posig, M. (2001), “Supervisory emotional support: an explanation of reverse buffering effects”,Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 328-44.

Parasuraman, A. (1987), “Customer-oriented corporate cultures are crucial to services marketing success”,Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 39-46.

Posig, M. and Kickul, J. (2003), “Extending our understanding of burnout: test of an integrated model in non-service occupations”,Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 3-19.

Schneider, B., White, S.S. and Paul, M.C. (1998), “Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: test of a causal model”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83 No. 2, pp. 150-63.

Thoits, P.A. (1995), “Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next?”,

Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 53-79.

A study of

frontline bank

employees

Appendix. Study variables

Dependent variables

Affective organizational commitment(adapted from Mowdayet al., 1979) (a¼ 0.89): (1) I talk up this bank to my friends as a great organization to work for. (2) I find that my values and the bank’s values are very similar. (3) I am proud to tell others that I work for this bank.

(4) This bank inspires the very best in me in the way of job performance. (5) I really care about the future of this bank.

(6) This bank earned my complete loyalty.

Job satisfaction(adapted from Babin and Boles, 1998) (a¼0.91): (1) My job is very pleasant.

(2) I am highly satisfied with my job. (3) I am very enthusiastic about my work. (4) I find real enjoyment in my work. (5) I definitely dislike my job. (6) My job is very worthwhile.

Job performance(adapted from Babin and Boles, 1998) (a¼0.76): (1) I am a top performer.

(2) I get along with customers better than others. (3) My performance is in the top 10 percent.

(4) I consistently deliver better quality service than others. (5) I have been rated consistently as a star performer. (6) I go out of my way to help customers.

Turnover intentions(adapted from Singhet al., 1996; Boshoff and Allen, 2000) (a¼0.82): (1) I will probably be looking for another job soon.

(2) I often think about quitting.

(3) I will quit this job sometime in the next year.

(4) It would not take too much to make me resign from this bank.

Independent variables

Supervisory support(adapted from Bellet al., 2004) (a¼0.86):

(1) My boss is very concerned about the welfare of those under him/her. (2) My boss is willing to listen to work-related problems.

(3) My boss can be relied on when things get difficult at work.

Training(adapted from Rogget al., 2001) (a¼0.82): (1) At this bank, sufficient time is allocated for training. (2) At this bank, sufficient money is allocated for training. (3) At this bank, training programs are consistently evaluated.

(4) At this bank, training programs focus on how to improve service quality.

Servant leadership(adapted from Lytleet al., 1998) (a¼0.90):

(1) Management constantly communicates the importance of service quality

IJBM

28,3

(2) Management regularly spends time “in the field” or “on the floor” with customers and frontline employees.

(3) Management is constantly measuring service quality.

(4) Managers give personal input and leadership into creating quality service.

(5) Management provides resources, not just “lip service, to enhance our ability to provide excellence service.

(6) Management shows they care about service by constantly giving of themselves.

Rewards(adapted from Lytleet al., 1998; Johnson, 1996) (a¼0.62): (1) We have financial incentives for service excellence.

(2) I receive visible recognition when I excel in serving customers. (3) My promotion depends on the quality of service I deliver.

Empowerment(adapted from Lytleet al., 1998):

(1) I often make important customer decisions without seeking management approval. (2) I have the freedom and authority to act independently in order to provide service

excellence.

Service technology/support(adapted from Lytleet al., 1998; Johnson, 1996) (a¼0.83): (1) We have “state of the art” technology to enhance our service quality.

(2) Sufficient money is allocated for technology to support my efforts to deliver better service.

(3) I have the necessary technology support to serve my customers better.

(4) Management works hard to make our systems and processes more customer-friendly.

Customer orientation(adapted from Donavanet al., 2004) (a¼ 0.86): (1) I enjoy nurturing my customers.

(2) I take pleasure in making every customer feel like he/she is the only customer. (3) Every customer problem is important to me.

(4) I thrive on giving individual attention to each customer. (5) I naturally read the customer to identify his/her needs. (6) I generally know what customers want before they ask. (7) I enjoy anticipating the needs of customers.

(8) I am inclined to read the customer’s body language to determine how much interaction to give.

(9) I enjoy delivering the intended service on time.

(10) I find a great deal of satisfaction in completing tasks precisely for customers. (11) I enjoy having the confidence to provide good service.

(12) I enjoy remembering my customers’ names. (13) I enjoy getting to know my customers personally.

Age

1¼18-34, 0¼35 and older.

Gender

1¼female, 0¼male.

A study of

frontline bank

employees

Education

1¼less than college, 0¼college or more.

Responses to statements comprising each multi-item variable were elicited on five-point scales ranging from 5¼Strongly agree to 1¼Strongly disagree.

About the authors

Ugur Yavas is Professor of Marketing and Advisory Board Faculty Fellow at East Tennessee State University. Besides theInternational Journal of Bank Marketing,he has contributed to such journals as theJournal of Marketing Research,Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Service Research, Journal of Business Research,Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, International Journal of Research in Marketing,European Journal of Marketing, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Journal of Services Marketing,Journal of

Consumer Marketing, Journal of World Business, Management Decision, and Long Range

Planning.

Emin Babakus is First Tennessee Professor and Professor of Marketing at the University of Memphis. He has contributed to such journals as theJournal of Marketing Research,Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of Service Research,Journal of Retailing,Journal of Services Marketing,Decision Sciences,Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, International Journal of Service Industry Management, andJournal of Advertising Research. Emin Babakus is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: [email protected]