Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Study of Undergraduate Student Intent to

Minor in Business: A Test of the Theory of Planned

Behavior

Datha Damron-Martinez , Adrien Presley & Lin Zhang

To cite this article: Datha Damron-Martinez , Adrien Presley & Lin Zhang (2013) A Study of Undergraduate Student Intent to Minor in Business: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behavior, Journal of Education for Business, 88:2, 109-116, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.657262

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.657262

Published online: 04 Dec 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 129

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.657262

A Study of Undergraduate Student Intent to Minor in

Business: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behavior

Datha Damron-Martinez, Adrien Presley, and Lin Zhang

Truman State University, Kirksville, Missouri, USAUndergraduate students are becoming aware of the edge that a business degree presents in the job hunt, yet many cannot justify the additional resources spent in obtaining a second major. A minor in business circumvents this constraint. The authors build on previous research into the motivations of students to choose a business minor by using Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior as a theoretical basis for indentifying the factors that might influence their intention to minor in an area of business. A survey administered to 617 nonbusiness undergraduate students, and subsequent analysis, supported Ajzen’s theory that attitude, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms all were significant predictors of intention.

Keywords: business minor, business student choice, theory of planned behavior

To meet the needs of students in today’s competitive envi-ronment, colleges and universities schools are seeking ways to increase the marketability of undergraduate students. By increasing exposure to a variety of academic courses and experiences, students can build a broader resume, enabling them to obtain positions within and outside of their major area of study. A common approach to achieve this exposure is through the completion of a minor program of study (As-sociation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, 2010; Gloeckler, 2007); some institutions, recognizing the impor-tance of providing such an opportunity for students, have recently added minor areas of study (Grau & Akin, 2011; Pierson & Troppe, 2010). While this opportunity is often en-couraged by academic advisors, not all students choose to participate; academicians search for a better understanding as to why. Questions exist as to the antecedents of student choice to choose a minor program of study.

This research was undertaken with a number of outcomes in mind. First, and primarily, we sought to achieve a better understanding of the motivations of undergraduate students in choosing a business minor. Second, it is believed that this understanding will assist in the recruitment of students by business programs. Third, students increasingly realize the need for additional education beyond their primary under-graduate degree preparation for success in today’s market

Correspondence should be addressed to Datha Damron-Martinez, Tru-man State University, School of Business, Violette Hall 2456, 100 E. Normal Street, Kirksville, MO 63501-4221, USA. E-mail: martinez@truman.edu

(Gloeckler, 2007); here we explore and contribute to the the-ory as well as to the veracity of this supposition.

The results of a study performed to analyze the factors which impact the attitude toward and likelihood of nonbusi-ness students pursue a businonbusi-ness minor program are presented. While other investigations have looked at undergraduate stu-dents and the choice of academic majors, factors related to the choice of a minor have been largely ignored. The re-search described uses the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), a widely accepted model from social psychology as its theoretical foundation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Research on Student Choice of Academic Major or Minor

Several studies have examined factors influencing student choice of academic majors in general and business disci-plines specifically. A review of the literature, however, failed to identify any previous research looking specifically at the student decision to minor in business.

Keillor, Bush, and Bush (1995) found that institutions facing decreased enrollment must consider the components of attraction to any area of study. Course offerings, profes-sor credibility, practical relevance of the particular courses and major, and the perceived quality of the institution and the program were significant factors. Keillor et al. contend that through the identification of the key criteria in major

110 D. DAMRON-MARTINEZ ET AL.

selection, institutions can use this information to communi-cate information to their target audience. Lowe and Simons (1996) also considered factors influencing student choice of business majors. They found that career options are fore-most for marketing majors whereas accounting, finance, and management majors rank future earnings as the most impor-tant influence with career options second, supporting pre-vious research (Cebula & Lopes, 1982; Fiorito & Dauffen-bach, 1982). Gnoth and Juric (1996) and, later, West, Newell, and Titus (2001) concurred. Kim, Markham, and Cangelosi’s (2002) also supported earlier findings; further inquiry in this study discovered the internal motivation of students to choose majors in which the type of work was of interest and matched their abilities. Strasser, Ozgur, and Schroeder (2002) agreed to some extent in their research but found that management was the only area where interest was correlated to decision. Malgwi, Howe, and Burnaby (2005) agreed.

Simons, Lowe, and Stout (2003) performed a compre-hensive literature of factors influencing choice of accounting as a major and found earnings were a lead factor. In their empirical study, Pritchard, Potter, and Saccucci (2004) es-tablished that areas of study in business, such as accounting, are often perceived as too quantitative for students who then choose another major. Also, accounting students typically take their introductory courses sooner than other business majors and, therefore, may choose a major earlier in their academic career than other students. This literature suggests that prospective business students need to be made aware of expectations and outcomes or opportunities available to them early in their academic career. Zhang (2007) looked specif-ically at the choice of information systems (IS) as a major; the research discovered IS majors cite referent influence in the form of social pressure as a deciding factor as well, and families and professors were identified as the salient referent groups.

Conversely, Leppel, Williams, and Waldauer (2001) looked exclusively at the impact of parents’ occupation and socioeconomic status on the students’ major choice and found that this may be the primary antecedent in a students’

major choice. Female students were more influenced by the fathers’ occupation and socioeconomic status, yet the oppo-site was true for male students in choosing a major.

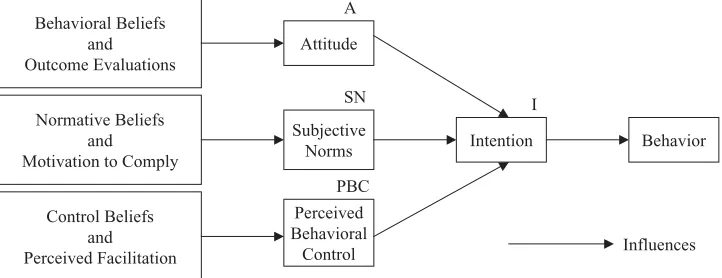

Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB is a widely studied model from social psychology, concerned with the determinants of consciously intended be-haviors (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). According to the TPB (see Figure 1), a person’s performance of a specified behavior is determined by that person’s behavioral intention to perform the behavior. This behavioral intention is, in turn, determined by three factors concerning the behavior in question: attitude toward the behavior (A), which refers to the degree to which the person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior in question; subjective norm (SN), which refers to the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior; and perceived behavioral control (PBC), de-fined as the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior. As a general rule, the more favorable the attitude and subjective norm with respect to a behavior, and the greater the perceived behavioral control, the stronger an individual’s intention to perform the behavior under consideration.

Each of these factors is further determined by a pair of secondary factors. Attitude is a function of products of be-havioral beliefs (the likelihood or extent to which an action will result in a particular outcome) and outcome evaluations (positive or negative evaluation of the desirability of the out-come). Subjective norms are determined by a person’s per-ceived expectation of specific referent individuals or groups multiplied by his or her motivation to comply with these ex-pectations. Perceived behavioral control depends on control belief (a perception of the availability of skills, resources, and opportunities) multiplied by perceived facilitation (an assess-ment of the importance of those resources to the achieveassess-ment of outcomes).

The TPB has been used in a wide range of behavioral science disciplines and empirically in a variety of situations to predict and understand behavior. In studies related to our

Behavioral Beliefs

FIGURE 1 The theory of planned behavior.

research, Cohen and Hanno (1993) utilized the TPB to study U.S. students’ choice of accounting as an academic major. All three factors, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived control, were significant and highly correlated to intention. Tan and Laswad (2006) extended and updated the Cohen and Hanno’s research applied to students in New Zealand. Overall, the results of both research projects reinforced the need for positive marketing of the accounting major in and out of the academic setting to dispel possible negative notions or perceptions about accounting as a major.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

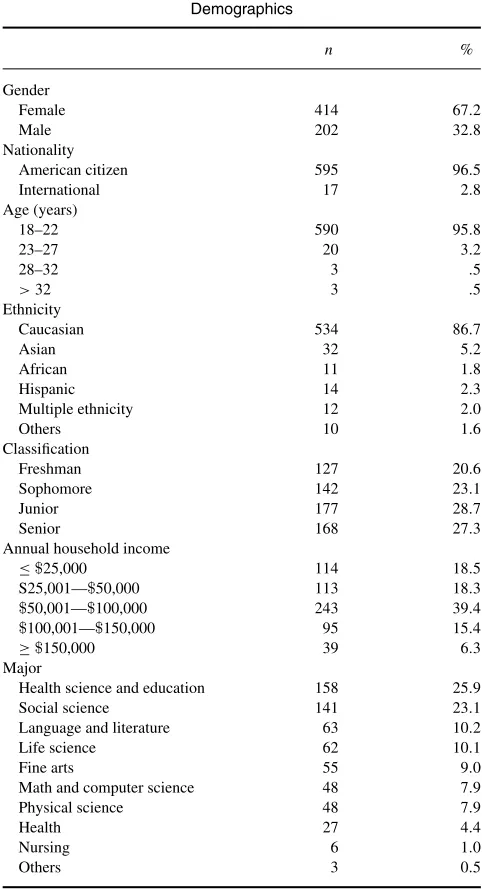

The target population selected was nonbusiness students at a single Midwest university recruited through an invitation email sent to 4,379 nonbusiness majors. Two reminder emails were sent one and two weeks later to increase participa-tion rate; participaparticipa-tion was voluntary and anonymous. Stu-dents accessed an online survey instrument, activated for two weeks, through a link provided in the email. After eliminating unusable questionnaires, 617 usable responses were gathered for a 14.1% usable response rate. Table 1 presents selected demographic attributes for the participants.

Instrument

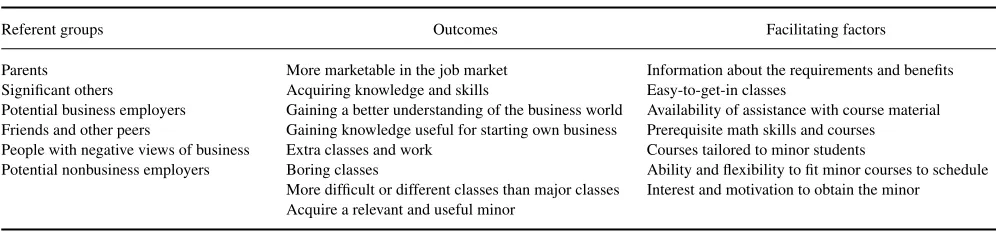

The items for the online survey were developed through a series of elicitation interviews conducted with a represen-tative sample of the target population. The interviews were conducted in three upper level courses to determine relevant (a) student referent groups to measure subjective norms, (b) relevant outcomes to measure attitude, and (c) relevant re-sources and opportunities to measure perceived behavioral control. Open-ended questions, asked to facilitate responses, were the following: What factors will positively/negatively influence your decision to obtain a business minor? Who would approve/disapprove of your decision to obtain a busi-ness minor? What factors would prevent you from/assist you in pursuing a business minor? Is there anything else that comes to mind when you think of a business minor?

The responses were classified and grouped according to similarities leading to the identification of the factors deemed most relevant for each of the elements of the TPB. Those fac-tors mentioned most often were chosen for incorporation into the full survey instrument. The final list of factors consisted of six referent groups, eight outcomes, and seven facilitating factors as shown in Table 2.

The referent groups were used to develop specific ques-tions to evaluate the elements of the TPB. The quesques-tions for the survey were developed using guidelines found in the literature (Ajzen, 1991; Mathieson, 1991) and a previously validated survey instrument described by Riemenschneider and McKinney (2001). The questions were formatted in a 7-point semantic differential scale (endpoints included

TABLE 1

American citizen 595 96.5

International 17 2.8

Age (years)

Caucasian 534 86.7

Asian 32 5.2

African 11 1.8

Hispanic 14 2.3

Multiple ethnicity 12 2.0

Others 10 1.6

Classification

Freshman 127 20.6

Sophomore 142 23.1

Junior 177 28.7

Health science and education 158 25.9

Social science 141 23.1

Language and literature 63 10.2

Life science 62 10.1

Fine arts 55 9.0

Math and computer science 48 7.9

Physical science 48 7.9

Health 27 4.4

Nursing 6 1.0

Others 3 0.5

strongly disagree/strongly agree, not at all/very much,

extremely negative/extremely positive, extremely unlikely/ extremely likely, and extremely unimportant/extremely im-portant, depending on the question). In addition, survey items designed to directly measure subjective norms, attitude, per-ceived behavioral control, and intention were developed. Ex-ample questions are shown in Table 3.

RESULTS

TPB Model

Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients of the three first level constructs (the independent variables) in the model for all respondents. All three constructs were significantly

cor-related with intention to pursue a minor (p≤.01).

112 D. DAMRON-MARTINEZ ET AL.

TABLE 2 Factors for Survey

Referent groups Outcomes Facilitating factors

Parents Significant others

Potential business employers Friends and other peers

People with negative views of business Potential nonbusiness employers

More marketable in the job market Acquiring knowledge and skills

Gaining a better understanding of the business world Gaining knowledge useful for starting own business Extra classes and work

Boring classes

More difficult or different classes than major classes Acquire a relevant and useful minor

Information about the requirements and benefits Easy-to-get-in classes

Availability of assistance with course material Prerequisite math skills and courses Courses tailored to minor students

Ability and flexibility to fit minor courses to schedule Interest and motivation to obtain the minor

According to the model of planned behavior, we also have three models describing the relationships between factors predicting attitude toward taking business minor, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control, respectively:

Attitude=αa+βa(behavior belief×outcome evaluation)

+ε

Subjective norm=αs+βs (normative belief×motivation

to comply)+ε

Perceived behavioral control=αp+βp(perceived facilitators

×control beliefs)+ε

Tables 5–8 present the regression model results for at-titude toward taking business minor. All estimated

regres-sion models are significant and consistent with theory predictions.

Individual Items

Relative importance of individual items was also investi-gated. The likelihood of experiencing positive outcomes were acknowledged by students: gaining a better understanding

of the business world (M =5.65 [higher more favorable],

SD=1.21), gaining knowledge useful for starting own

busi-ness (M=5.36,SD=1.03), acquiring knowledge and skills

that can be used in everyday life (M =5.00,SD =1.32),

becoming more marketable in the job market (M = 4.88,

SD=1.47), and acquire a relevant and useful minor (M =

TABLE 3 Example Survey Questions

Subjective norms: determined by a person’snormative beliefs(perceived expectation of specific referent individuals or groups) and his or hermotivation to complywith these expectations

•Direct measure (3 items): Most people whose opinions I value would of my obtaining a business minor. Strongly disapprove↔Strongly approve

•Normative belief (6 items): My parents would look favorably on my obtaining a business minor. Strongly disagree↔Strongly agree

•Motivation to comply (6 items): How much do you care whether your parents approved or disapproved of your choice of pursuing a business minor? Not at all↔Very much

Attitude: a function ofoutcome evaluations(positive or negative evaluation of the desirability of the outcome) andbehavioral beliefs(the likelihood or extent to which an action will result in a particular outcome).

•Direct measure (5 items): Obtaining a business minor is Bad↔Good

•Outcome evaluation (7 items): Making myself more marketable in the job market is Extremely negative↔Extremely positive

•Behavioral belief (7 items): If I obtain a business minor, it is that I would make myself more marketable in the job market. Extremely unlikely↔Extremely likely

Perceived behavioral controlis a function ofcontrol beliefs(a perception of the availability of skills, resources, and opportunities) andperceived facilitation(an assessment of the importance of those resources to the achievement of outcomes).

•Direct measure (4 items): For me to obtain a business minor would be. . . Extremely difficult↔Extremely easy

•Control belief (9 items): With regards to my decision to obtain a business minor, having information about the requirements and benefits of a business minor is. . .

Extremely unimportant↔Extremely important

•Perceived facilitation (9 items): It that I would have information about the requirements and benefits of a business minor. Extremely unlikely↔Extremely likely

Intention

•Direct measure (3 items): I plan to obtain a business minor. Extremely unlikely↔Extremely likely

4.66,SD=1.55). For the likelihood of experiencing nega-tive outcomes, the following results were seen: extra classes

and work (M=5.36,SD=1.63), boring classes (M=4.89,

SD=1.21), and more difficult or different classes than major

classes (M=4.29,SD=1.62).

The survey data also suggest that students consider the

benefits of acquiring knowledge and skills (M =6.20,SD

=1.24), becoming more marketable in the job market (M=

6.06,SD=1.45), acquiring a relevant and useful minor (M=

5.79,SD=1.63), and gaining knowledge useful for starting

own business (M=5.21,SD=1.21), as most the favorable

outcomes of acquiring a business minor. Data also indicated that taking boring classes was the biggest concern of students

(M=2.82,SD=1.06), followed by taking more difficult or

different classes than major classes (M=3.61,SD=1.07),

and extra classes and work (M=3.99,SD=1.37).

Interest and motivation to obtain the minor, and ability and flexibility to fit minor course to schedule were considered as the top factors affecting (either positively or negatively)

students’ choice (Ms=6.02 [SD =1.61] and 5.86 [SD=

1.49]) while prerequisite math skills and courses, and courses tailored to minor students were considered the least likely

to affect their decision (Ms= 4.79 [SD =1.51] and 5.17

[SD=1.71], respectively). However, students perceived that

interest and motivation to obtain the minor and the ability

and flexibility to fit minor courses to schedule (Ms=3.30

[SD =1.61] and 3.34 [SD=1.52], respectively) were the

factors that would least likely occur as inhibiting factors. When taking other’s opinions into consideration, students tend to most value future business and nonbusiness

em-ployer’s view (Ms=4.63 [SD=1.65] and 4.03 [SD=1.39],

respectively) while opinions of people with negative views of business, and friends and other peers were least important

(Ms=2.50 [SD=1.63] and 3.05 [SD=1.61], respectively).

At the same time, they thought future business employers

and parents were mostly likely to favor their decision (Ms=

5.39 [SD=1.63] and 4.97 [SD=1.25], respectively).

Group Differences

Analysis was also conducted to see if there were differences in opinions among various groups of respondents. With re-spect to behavioral beliefs, female students were more likely

to believe that they can acquire knowledge and skills,F=

4.927,p=.027; gain a better understanding of the business

world,F=4.697,p=.031; would experience extra classes

and work,F=5.672,p=.018; and would have to take more

difficult or different classes than their major classes, F =

4.711, p=.030, than were male students. Female students

were more likely to identify the importance of the outcome

evaluations of being more marketable in the job,F=10.051,

p =.002; acquiring knowledge and skills,F =4.113,p=

.043; and acquiring a relevant and useful minor,F=8.441,p

=.004, than were male students. Female students also were

more likely to comply with the opinions of their parents,F=

TABLE 4

Subjective norm .121∗

∗p<.01.

TABLE 5

Model Construct for Attitude Toward Business Minor

Coefficient SE t p

Model Construct for Subjective Norms of Business Minor

Model Construct for Perceived Behavior Control of Business Minor

Perceived control 0.193 0.031 .000

Note. n=616,R2=.385.

114 D. DAMRON-MARTINEZ ET AL.

17.003,p<.000; potential business employers,F=16.082,

p<.000; and nonbusiness employers,F=9.129,p=.003.

Female students valued the importance of most facilita-tors more than male students. Specifically, they stated the importance of having information about the requirements

and benefits of a business minor,F=9.098,p=.003;

hav-ing classes that are easy to get into,F=8.774,p=.003; the

availability of assistance with course material,F=14.161,

p<.000; having prerequisite math skills and courses,F=

11.090,p =.001; and the availability of course especially

tailored to minors, F =7.302, p =.007. Female students

were less likely to perceive that they would have

easy-to-get-into classes,F=4.277,p=.039, and ability and flexibility

to fit minor courses to schedule,F=5.761,p=.017, than

were male students.

In general, female students were more likely to believe that taking a business minor would benefit them, and believed those benefits would be important for them. They were more likely to be influenced by their parents and potential employ-ers when making decisions about business minor, and were more concerned about whether facilitating factors would be available, were less optimistic in the availability of courses specially tailored to a minor, and ability and flexibility to work required courses into their schedule.

When looking at class standing, lower level students (freshmen and sophomores [FS]) were more likely to believe that a business minor would be a relevant and useful minor

than were upper level juniors and seniors (JS),F=4.034,p=

.045. Meanwhile, lowerclassmen were more likely to think that by acquiring a business minor, they would be required to take classes which were more difficult or different than

courses of their major,F =4.707,p =.030. FS had more

interests and motivation to gain knowledge useful for

start-ing their own business,F=9.961,p=.002, and acquiring a

relevant and useful minor,F=–1.151,p=.002, than did JS.

They were also less concerned about taking extra classes and

work,F=14.405,p<.000, and boring classes,F=2.056,

p =.152. This finding is intuitive, as JS are further into a

chosen area of study, and potentially less willing to deviate from an established plan toward graduation.

There was no significant difference between classes in their likelihood to comply with other people’s opinions. FS also showed perceiving a higher value in the availability of more information about the requirements and benefits of a

business minor,F=5.773,p=.017, and the availability of

assistance with course material,F=4.637,p=.032, than did

JS. Finally, FS had more interests and motivations to obtain

the minor than JS,F=11.703,p=.001, again probably due

to where they are positioned in courses completed toward a graduation plan.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Theoretical Implications

The results of this research evidence that TPB can improve our understanding of the factors that determine a student’s

intention to minor in business. The three predictor variables, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, each amplified the prediction of student intention to minor in business. As expected from previous research on student choice of major area of study, the results are consistent with predictions that students’ behavior belief combined with the outcome evaluation influences their attitudes toward the in-tention to pursue a business minor. Many factors are mea-sured by a student in considering the benefits and concerns of pursuit of a minor in business; the TPB model captures this as well as the individual likelihood of a negative out-come. Additionally, this research increases the robustness in characterizing the range of student considerations in this de-cision to the work of other researchers studying choice of major (Galotti, 1999; Lowe & Simons, 1997; Malgwi et al., 2005; Pritchard et al., 2004). The results are consistent with the previous TPB predictions that students’ perceived facili-tators and control beliefs influence their perceived behavior control. Finally, the result of the present study supported that students’ subjective norm was significantly influenced by normative beliefs and motivation to comply. Especially in a traditional college-age group, it was expected that a stu-dent would seek out opinions of respected referent groups when making a decision of this magnitude. In conclusion, the model for the TPB is a robust fit to determine intention in student decision-making about a business minor choice.

Practical Implications

The findings of this research support many positive prac-tical implications for academicians developing curriculum, recruitment practitioners within the higher education setting, and academicians involved in the development, promotion, and outcomes of minor areas of study in business. As the research showed that female students tended to identify the benefit of increased marketability in the job market, material developed and aimed toward them should remind this seg-ment of this point. Material developed and aimed toward men should be more informative in nature, explicitly emphasizing the benefits of obtaining a minor in business. Material dis-cussing the business minor aimed toward women should also emphasize the similarity of courses between other majors and courses in business, and emphasize the ease of completion of a minor, reducing perceived risk for the female segment; ei-ther a value-added approach or a cost-benefit approach would be beneficial.

Material promoting positive outcomes of obtaining a busi-ness minor should be sent to parents and future employers, as these influencers could offer positive reinforcement for students, especially women, considering a business minor. When promoting the study of a business minor, practitioners should highlight the benefits of gaining a better understand-ing of the business world through attainment of a business minor for all students, emphasizing evidence of the increased marketability of a student in his or her chosen area of study. As the fear of boring classes was the biggest concern of the sample, followed by the concern of course difficulty

and dissimilarity to major courses currently enrolled in, em-phasis should be placed on exciting courses and offerings within the school of business. Information should be given about participation in service learning and other hands-on ap-proaches utilized within the business program. A school of business should offer nonbusiness students opportunities to attend business lectures and to interact with business faculty to better align the students’ perception with reality. Model programs of study could be developed with advisors in other major areas to ensure that students considering a business minor perceive the courses are readily available, seats within classes are easy to obtain, and a realistic projection of a graduation date can be established.

Information provided to students should stress perspec-tives of future employers. Schools of business should also develop a campaign directed at potential employers who hire across majors and distribute this literature through a com-mon avenue, such as a university’s Career Center. This tact is taken to serve as an avenue of influence towards a student de-bating the choice of obtaining a business minor; an employer can emphasize the benefits of this experience and knowledge to students during career fairs and interviews. This can serve as not just a marketing tool to increase interest and enroll-ment in a business minor for existing students, but also as a marketing tool for freshman recruitment. Although intu-itive, information about business minors should be tailored toward underclassmen, regardless of chosen major, as this is the most receptive segment with the flexibility still available in their academic advising plan.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Several areas where the research could be extended were identified. Whereas in this study we focused on attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as an-tecedents to intention, exploration of the question, “Does the student intending to pursue a minor in business actually ob-tain that minor?” would be helpful. This would add cerob-tainty to this study as well as increase the validity and robust-ness of future work. Performing this study would contribute significantly to the TPB literature, assisting practitioners in determining what methods of marketing business minors are actually successful.

As posited in the research by Ajzen and Driver (1992) the role of involvement is an area ripe for study in TPB; this appears especially so in the higher education setting. Actual involvement may be measured through self-assessment, or a proxy such as GPA or cocurricula activities could be utilized. Building on additional research by Ajzen, Czasch, and Flood (2009) the call remains clear to further study the relationship between the construct conscientiousness and its effect on intentions and actual performed behavior, easily measured in a student population.

Utilizing the research of Carnevale, Stohl, and Melton (2011), additional research could include the study of the economic value of a minor in business. As many art and hu-manities majors are employed in sales, marketing, and other business-related occupations as cited in this study, could a minor in business increase the annual income and marketabil-ity of these nonbusiness majors even marginally? A focus by schools of business on business minors could serve to address the problem of decline of enrollments within the area of busi-ness. Building on this initiative, as suggested in the Carnevale et al. (2011) research, institutions of higher education should match incoming majors (supply of labor) with demand in the market. Research should investigate whether the addition of a business minor to the toolbox of non-business graduates would increase these students’ employability.

As discussed by Relyea, Cocchiara, and Studdard (2008), with students’ perceptions of risk and value, it may be a dif-ficult and complicated process to motivate students to minor in business. The literature does not support the idea that non-business students have embraced the concept of increasing marketability through attainment of a business minor. Addi-tionally, as “risk is determined by the individual’s perception based upon quantity of time, availability of information, and control over the situation” (Relyea et al., p. 356) universi-ties must determine what can be done to ameliorate these three components of risk—from financial assistance should a minor increase a students matriculation period, to easy ac-cess to business courses, to information reducing the negative perception of business course work by nonbusiness majors.

Limitations

Among the limitations of the research, a lower external va-lidity of findings may exist as the sample was taken from one institution with a fairly homogeneous population. The re-search was conducted within the population of a liberal arts university that might differ from characteristic of non–liberal arts university students (Salisbury, Umbach, Paulsen, & Pas-carella, 2009). While statistics show that the average U.S. student studying business is White (76%) and male (55%), the predominant characteristics of students at the school un-der study are White and female, possibly skewing the data.

Cohen and Hanno (1993) ensured that a measure was in place in their research to account for students who had already made a decision to major prior to participating in the research, whereas this research only excluded current students majoring in business, not those who might have made the decision to obtain a minor, but not yet officially declared. This is a limitation as students were being asked to recall a previously held belief.

Finally, the economic times and job market existing when the research was conducted might have served to encour-age or discourencour-age students to consider minor in business or, at the least, could send conflicting messages of the impor-tance of the study of business. In a different market, student

116 D. DAMRON-MARTINEZ ET AL.

response could vary. Conversely, in the recent spate of ethical breaches within the business arena, students holding strong moral and ethical attitudes might be off put by news in the media and, therefore, hold negative impressions about the area of business in general.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., Czasch, C., & Flood, M. G. (2009). From intentions to behavior: Implementation intention, commitment, and conscientiousness.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,39, 1356–1372.

Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24, 207– 224.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980).Understanding attitudes and predicting behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2010, June 19). The demand for business degrees continues, creating a positive outlook for business schools.eNewsline: Management Education News from AACSB International. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/ publications/enewsline/archives/2010/vol9-issue4-business-degree-demand.pdf

Carnevale, A. P., Stohl, J., & Melton, M. (2011). What’s it worth? The economic value of college majors. Washington, DC: Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University.

Cebula, R. J., & Lopes, J. (1982). Determinants of student choice of un-dergraduate major field. American Educational Research Journal,19, 303–312.

Cohen, J. & Hanno, D. M. (1993). An analysis of underlying constructs affecting the choice of accounting as a major.Issues in Accounting Edu-cation,8, 219–238.

Fiorito, J., & Dauffenbach, R. C. (1982). Market and nonmarket influences on curriculum choice by college students.Industrial and Labor Relations Review,36, 88–101.

Galotti, K. M. (1999). Making a ‘major’ real-life decision: College students choosing an academic major.Journal of Educational Psychology,91, 379–387.

Gloeckler, G. (2007, March 9). The major attraction of a business minor.

BusinessWeek Online, 11.

Gnoth, J., & Juric, B. (1996). Students’ motivation to study introductory marketing.Educational Psychology,16, 389–405.

Grau, L., & Akin, R. (2011) Experiential Learning for nonbusiness students: Student engagement using a marketing trade show.Marketing Education Review,21, 69–78.

Keillor, B. D., Bush, R. P., & Bush, A. J. (1995). Marketing-based strategies for recruiting business in the next century.Marketing Education Review,

5(3), 69–79.

Kim, D. F., Markham, S., & Cangelosi, J. D. (2002). Why students pursue the business degree: A comparison of business majors across universities.

Journal of Education for Business,78, 28–32.

Leppel, K., Williams, M. L., & Waldnauer, C. (2001). The impact of parental occupation and socioeconomic status on choice of college major.Journal of Family and Economic Issues,22, 373–394.

Lowe, D. R., & Simons, K. (1997). Factors influencing a choice of busi-ness majors – some additional evidence: a research note.Accounting Education,6, 39–45.

Malgwi, C. A., Howe, M. A., & Burnaby, P. A. (2005). Influences on students’ choice of college major.Journal of Education for Business,80, 275–282.

Mathieson, K. (1991). Predicting user intentions: comparing the technol-ogy acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior.Information Systems Research,2, 173–191.

Pierson, M., & Troppe, M. (2010) Curriculum to career.Peer Review,12(4), 12–14.

Pritchard, R. E., Potter, G. C., & Saccucci, M. S. (2004). The selection of a business major: Elements influencing student choice and implications for outcomes assessment.Journal of Education for Business,79, 152– 156.

Relyea, C., Cocchiara, F. K., & Studdard, N. L. (2008). The effect of per-ceived value in the decision to participate in study abroad programs.

Journal of Teaching in International Business,19, 346–361.

Riemenschneider, C., & McKinney, V. (2001). Assessing belief differences in small business adopters and non-adopters of web-based e-commerce.

The Journal of Computer Information Systems,42, 101–107.

Salisbury, M. H., Umbach, P. D., Paulsen, M. B., & Pascarella, E. T. (2008). Going global: Understanding the choice process of the intent to study abroad.Research in Higher Education,50, 119–143.

Simons, K. A., Lowe, D. R., & Stout, D. E. (2003). Comprehensive literature review: Factors influencing choice of accounting as a major.Journal of the Academy of Business Education,5, 97–110.

Strasser, S. E., Ozgur, C., & Schroeder, D. L. (2002). Selecting a business college major: an analysis of criteria and choice using the analytical hierarchy process. Mid-American Journal of Business, 17, 47–56.

Tan L. M., & Laswad, F. (2006). Students’ beliefs, attitudes and intentions to major in accounting.Accounting Education: an International Journal,

15, 167–187.

West, J., Newell, S., & Titus, P. (2001). Comparing marketing and non-business students’ choice of academic field of study.Marketing Education Review,11, 75–82.

Zhang, W. (2007). Why IS: Understanding undergraduate students’ inten-tions to choose an information systems major.Journal of Information Systems Education,18, 447–458.