Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:31

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Faculty Ownership of the Assurance of Learning

Process: Determinants of Faculty Engagement and

Continuing Challenges

Michael J. Garrison & Richard J. Rexeisen

To cite this article: Michael J. Garrison & Richard J. Rexeisen (2014) Faculty Ownership of the Assurance of Learning Process: Determinants of Faculty Engagement

and Continuing Challenges, Journal of Education for Business, 89:2, 84-89, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.761171

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.761171

Published online: 17 Jan 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 98

View related articles

View Crossmark data

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.761171

Faculty Ownership of the Assurance of Learning

Process: Determinants of Faculty Engagement

and Continuing Challenges

Michael J. Garrison and Richard J. Rexeisen

University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA

Although this article provides further evidence of serious impediments to faculty ownership of assurance of learning, including inadequate and misaligned resources, the results indicate that faculty can be energized to become actively engaged in the assurance of learning (AOL) process, particularly when they believe that AOL results are useful and help students prepare for future business challenges. The authors suggest strategies for building a more engaged faculty as well as highlighting ongoing challenges in that process.

Keywords: AACSB, assurance of learning, faculty engagement

In 2003, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) adopted a new approach to the as-sessment of student learning requiring accredited schools to demonstrate that students are developing the skills and com-petencies that their curriculum is designed to deliver, and that the representations made to critical stakeholders about learning outcomes are accurate. To meet the continuous im-provement and accountability objectives of the assurance of learning (AOL) standards, business schools are required to develop mission-driven learning goals and objectives for all of their degree programs, create processes to directly assess whether students in those programs are meeting those goals, and adjust degree program curricula if student weaknesses are revealed. Rather than rely on surveys of alumni and em-ployers (indirect measures), business schools must directly assess student knowledge and skills.

Faculty ownership of the AOL process is both expected and required. Because AOL is part of a healthy curriculum management process, and faculty have traditionally assumed academic control of the curriculum, AACSB deemed faculty engagement in the assessment process critical to assurance of learning. Language in the standards, and consistent inter-pretive statements at AACSB workshops and AOL seminars, reinforces this new reality. Within this context faculty must define the “school’s learning goals,” “decide where the goals

Correspondence should be addressed to Richard J. Rexeisen, University of St. Thomas, Department of Marketing, Mail # MCH 316, 2115 Summit Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55105, USA. E-mail: rjrexeisen@stthomas.edu

are addressed within degree curricula,” “establish monitoring mechanisms to ensure that the proper learning experiences occur,” and “operationalize the learning goals by specifying or developing the measurements that assess learning achieve-ment on the learning goals” (AACSB, 2013, p. 62).

From the beginning of the implementation of the AOL standards, problems with faculty engagement have been noted by schools and reported in the literature. Martell’s (2007) survey of business school deans in 2004 and 2006 revealed a slow, gradual development of AOL systems as institutions adjusted to the new requirements. A third of the deans in both 2004 and 2006 worried about faculty resistance to assurance of learning. The lack of faculty knowledge about AOL was a concern, although the percentage of deans wor-ried about this declined from 62% in 2004 to 47% in 2006. Finally, the time required for assessment activities, a factor related to effective faculty engagement, became the domi-nant concern of deans, with 68% of respondents citing this as a worry in 2006, up from 54% in 2004.

One factor contributing to both faculty resistance and the time required for AOL is the common utilization of instru-ments administered in courses to assess student learning. Course-embedded measures are cited by Martell (2007) as the dominant form of direct measure employed by business schools. These measures often impose an additional require-ment on some but not all faculty, who may then resent the interference with their courses and the burden of implemen-tation.

Faculty resistance continued to be an area of focus in studies examining AOL implementation. Pringle and Michel

FACULTY OWNERSHIP OF THE ASSURANCE OF LEARNING PROCESS 85

(2007) conducted a survey of assessment coordinators identi-fied by deans of AACSB-accredited business schools in 2006 and reported that forty-three percent of schools experienced at least some faculty resistance to assessment. As expected, they found two key variables affecting the level of that re-sistance, which were characterized as inconvenience (time, added complexity, lack of knowledge) and fear of improper use of assessment data.

Pringle and Michel (2007) noted that the increasing amount of time necessary for assessment, a key factor in faculty resistance, was compounded by multiple reporting requirements imposed by AACSB, regional accrediting bod-ies, and others. Rather than mere inconvenience, faculty may feel overloaded with activities that make their teaching more difficult. They also posit, however, that if faculty believe that assessment leads to meaningful improvements in student learning, faculty will view the process as more favorable and be more actively involved in it. To the extent that assess-ment is undertaken primarily for compliance purposes, this imperils faculty buy-in.

Brocker (2007) examined faculty engagement in the AOL process through the lens of Ajzen’s (1988) Theory of Planned Behavior. As a consequence, her focus was primarily on de-termining the degree to which subjective norms and attitu-dinal variables predict intentions and then subsequently can be used to predict and understand behavior. Her sample in-cluded a mix of faculty with teaching and/or administrative duties. Similar to Pringle and Michel (2007), Brocker found the primary barriers to participation in assessment activities to be “lack of time, lack of reward, and fear of punishment” (p. 133).

Kelley, Tong, and Choi (2010) conducted a survey of AACSB deans examining the extent of faculty involvement in assessment and the level of faculty resistance. Deans sur-veyed continued to report a moderate level of resistance with time, lack of knowledge, and fear of improper use of the AOL findings being cited as the primary faculty concerns. The authors concluded that because most schools mandated participation in AOL activities, one would expect greater faculty resistance than was reported by the deans surveyed.

Rexeisen and Garrison (2013) conducted a study of how the closing-the-loop (CTL) process is being implemented in AACSB schools of business. The survey found that schools currently face very serious challenges to systematically im-plementing curricular interventions in response to AOL data, including the time necessary to develop, initiate and then re-evaluate the effectiveness of CTL actions. Even so, 71% of the respondents cited challenges related to faculty ownership of the AOL process as their primary future challenge.

The present study extends previous research by focusing on identifying those factors that differentiate levels of faculty engagement and it sheds light on how business schools can energize faculty to become actively engaged in the AOL process. It is also the first study to exclusively survey faculty (rather than deans, administrators or some combination of

faculty and administrators) to determine faculty perceptions of the factors that enhance or ensure faculty ownership of the process, as well as the continuing challenges to such active faculty engagement.

METHODOLOGY

A systematic random sample of 100 U.S. AACSB-accredited business schools were selected for this study, representing approximately 20% of all AACSB-accredited schools in the United States. Data were collected in two phases. The Dean of each school was contacted to ask permission for the study and then asked to identify a nonadministrative faculty person who understands the AOL process (key informant) in their program. Two follow-up reminders were sent resulting in a usable response rate of 36%.

In the second phase of the study key informants were contacted concerning the assurance of learning activities in their school. Two email reminders were automatically sent to subjects followed by a telephone request that resulted in 31 schools completing the survey.

The survey instrument comprised 40 questions designed to measure the level and importance of faculty involvement in the various stages of the AOL process. Questions also focused on current AOL practices, attitudes, and perceived future challenges. Data were collected during spring semester of 2012.

RESULTS

The study represents a cross-section of both public (67.7%) and private schools. Full-time faculty size ranged from 10 to 120 with a mean of 54. Average number of years that schools report having an active AOL program ranged from 4 to 20 with a mean of 7.8 years.

To understand the current state of faculty ownership, we measured faculty engagement in and energy for the AOL process. Faculty engagement is defined in our study by the key informant’s estimate of the percentage of faculty who are actively engaged in the AOL process in their school. Energy levels are measured using an interval scale where the key informant estimates faculty’s energy on a scale ranging from very high to very low. Faculty engagement is evenly distributed within the sample with a range of 9–100%, a mean of 50%, and standard deviation of 31.65%. Faculty energy levels ranged from very high to very low with a mean of 2.8 on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (high energy) to 5 (very little energy).

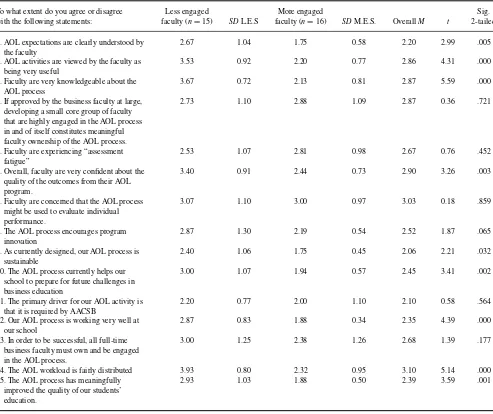

Faculty engagement in the AOL process helped to ex-plain a wide range of attitudes and behaviors (Table 1). More engaged faculty report a better understanding of AOL expectations and are overall more knowledgeable of the AOL process when compared to less engaged faculty. More

TABLE 1

Differences Between Schools That Are More Engaged as Opposed to Less Engaged

To what extent do you agree or disagree Less engaged More engaged Sig. with the following statements: faculty (n=15) SDL.E.S faculty (n=16) SDM.E.S. OverallM t 2-tailed 1. AOL expectations are clearly understood by

the faculty

2.67 1.04 1.75 0.58 2.20 2.99 .005 2. AOL activities are viewed by the faculty as

being very useful

3.53 0.92 2.20 0.77 2.86 4.31 .000 3. Faculty are very knowledgeable about the

AOL process

3.67 0.72 2.13 0.81 2.87 5.59 .000 4. If approved by the business faculty at large,

developing a small core group of faculty that are highly engaged in the AOL process in and of itself constitutes meaningful faculty ownership of the AOL process.

2.73 1.10 2.88 1.09 2.87 0.36 .721

5. Faculty are experiencing “assessment fatigue”

2.53 1.07 2.81 0.98 2.67 0.76 .452 6. Overall, faculty are very confident about the

quality of the outcomes from their AOL program.

3.40 0.91 2.44 0.73 2.90 3.26 .003

7. Faculty are concerned that the AOL process might be used to evaluate individual performance.

3.07 1.10 3.00 0.97 3.03 0.18 .859

8. The AOL process encourages program innovation

2.87 1.30 2.19 0.54 2.52 1.87 .065 9. As currently designed, our AOL process is

sustainable

2.40 1.06 1.75 0.45 2.06 2.21 .032 10. The AOL process currently helps our

school to prepare for future challenges in business education

3.00 1.07 1.94 0.57 2.45 3.41 .002

11. The primary driver for our AOL activity is that it is required by AACSB

2.20 0.77 2.00 1.10 2.10 0.58 .564 12. Our AOL process is working very well at

our school

2.87 0.83 1.88 0.34 2.35 4.39 .000 13. In order to be successful, all full-time

business faculty must own and be engaged in the AOL process.

3.00 1.25 2.38 1.26 2.68 1.39 .177

14. The AOL workload is fairly distributed 3.93 0.80 2.32 0.95 3.10 5.14 .000 15. The AOL process has meaningfully

improved the quality of our students’ education.

2.93 1.03 1.88 0.50 2.39 3.59 .001

Note: The responses were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). AOL=assurance of learning; less engaged=<50% reporting faculty are engaged; more engaged=>50%.

engaged faculty view AOL as more useful and are signif-icantly more confident about the quality of the outcomes from their AOL programs. By contrast less engaged faculties tend to view the AOL workload as unfairly distributed and are less inclined to view the process as sustainable or making a meaningful contribution to the quality of their students’ education. Less engaged faculty also lack confidence about whether the AOL process is helping their school to prepare for future challenges in business education.

Faculty informants generally agree that faculty are expe-riencing assessment fatigue and that the primary driver for their AOL activities is that it is required by AACSB. The sample was split over the issue of whether a small, highly dedicated core group of faculty can in and of itself constitute a meaningful faculty ownership of the AOL process

(ques-tions 4 and 13, Table 1), with 39% of the sample agreeing with the proposition, 32% unsure, and 29% disagreeing.

To further our understanding of the properties of faculty ownership, we conducted an exploratory analysis using a stepwise regression to identify those variables that may help to explain both faculty engagement and faculty energy for the AOL process. With regard to faculty engagement, three significant models emerged using the fifteen statements listed in Table 1 as the independent variables. Multicollinearity tol-erance ranges for all models are within acceptable toltol-erance ranges (O’Brien, 2007) with model one ranging between .498 and .987, model two between .472 and .949, and model three between .408 and .942. As illustrated in Table 2, knowl-edge of the AOL process accounted for 57.5% of the overall adjusted variance in the models. The addition of workload

FACULTY OWNERSHIP OF THE ASSURANCE OF LEARNING PROCESS 87

TABLE 2

Stepwise Regression Entering 15 Core Belief Statements and Predicting Percentage of Faculty

Engaged

Model r R2 AdjustedR2

SEof the

estimate Fchange Sig.Fchange

1 .768a .589 .575 20.665 40.190 .000 2 .807b .651 .626 19.391 4.799 .037 3 .847c .718 .685 17.783 6.105 .020

aPredictors: (constant), knowledgeable.

bPredictors: (constant), knowledgeable, work fairly distributed. cPredictors: (constant), knowledgeable, work fairly Distributed, faculty must own assurance of learning.

distribution and a grounding belief that faculty should own the AOL process resulted in a model that accounted for 68.5% of the adjusted variance. It is interesting to observe that fac-ulty engagement is not correlated with the number of years that a school reports having an active AOL program (r=

–.046).

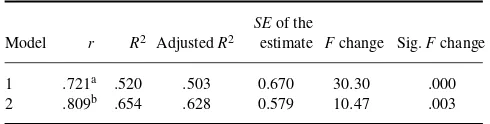

In a parallel exploratory analysis we assessed which of the 15 core attitude measures would predict the level of en-ergy faculty have for the AOL process (Table 3). Again, multicollinearity tolerance ranges for all models are within acceptable tolerance ranges with model one ranging between .563 and .995 and model two ranging between .544 and .970. The belief that “AOL is useful” accounted for 50.3% of the adjusted variance in faculty energy followed by “AOL helps to prepare our business school for the future” in model two accounting for an additional 12.5% of the variance.

Approximately half of the schools (54.8%) in our study reported that they had some form of a faculty development plan focused on AOL. Only 25.8% of the schools, however, reported that they used any form of incentive or reward to engage faculty in the AOL process. Of those schools that did reward involvement in the AOL process, grants, course releases, and recognition were cited most frequently as the means for incentivizing faculty engagement.

Respondents were also asked to identify the major chal-lenges to engaging faculty and the actions that the school had

TABLE 3

Stepwise Regression Entering 15 Core Belief Statements and Predicting Level of Faculty Energy for

AOL Activities

Model r R2 AdjustedR2

SEof the

estimate Fchange Sig.Fchange 1 .721a .520 .503 0.670 30.30 .000 2 .809b .654 .628 0.579 10.47 .003

aPredictors: (constant), assurance of learning (AOL) useful. bPredictors: (constant), AOL useful, helps prepare for future.

taken that had a meaningful and enduring impact on engag-ing faculty in the AOL process. Table 4 summarizes the top five answers to the question asking respondents to identify what they saw as the biggest challenge to engaging faculty in the AOL process. The number one response was “inade-quate or misaligned resources.” Resource-related comments often took the form of “there is a lack of clear and consis-tent message concerning how faculty should prioritize their attention,” “faculty have too many other commitments,” or “there are insufficient economic rewards for being engaged in the process.”

The sustainability of the AOL process and the need for fur-ther evidence that the AOL process improves the education experience of students tied for the second most frequently cited AOL challenge. This was followed closely by “there is a lack of knowledge or expertise with the AOL process.” Some respondents commented that the lack of knowledge and expertise is exacerbated by having to continuously introduce new faculty to the ongoing AOL process, primarily as a con-sequence of having to rotate new faculty into AOL committee responsibilities. The concern for sustainability appears to be a bridge concept linking resource allocation, expertise and proof of meaningful effectiveness.

The relatively minor reference to fear in our study is note-worthy in that previous studies report more concern in this arena, particularly in regard to how the AOL information is going to be used to evaluate faculty or constrain individual faculty teaching methods.

In terms of the responses relating to actions taken by schools that had a meaningful impact on faculty engage-ment, developing academic structures that support faculty engagement—assessment centers and assessment directors, for example—was cited by a number of schools. Similarly, schools mentioned processes that effectively engage faculty, including annual assessment workshops and annual assess-ment weeks. Regularly sharing AOL results at faculty meet-ings and through other communication mechanisms (e.g., newsletters) was also noted. It is noteworthy however that one-in-five (22%) report that none of their actions has had a meaningful impact on faculty engagement.

TABLE 4

Biggest Challenge to Engaging Faculty in the AOL Process

Observed challenge n % Inadequate and/or misaligned resources 16 51.6 Sustainability of the AOL process 7 22.6 Need proof that AOL improves education of students 7 22.6 Lack of knowledge and application skills 6 19.4

Fear 2 9.5

Note: Respondents in some instances listed more than one major chal-lenge. AOL=assurance of learning.

DISCUSSION

We began our study with the suspicion that faculty owner-ship of the AOL process must be viewed from the perspective of both engagement and faculty energy. We expected some overlap between the constructs and we found that engage-ment and energy are correlated (r=.60). However, as the exploratory stepwise regression (Tables 2 and 3) suggests, faculty energy for the AOL process and their engagement in the process are accounted for by different factors. Faculty en-gagement is driven by inputs (resources such as knowledge, expertise, allocation of workload and perceived responsibil-ity for AOL), whereas faculty energy for the process is driven by perceived outputs (evidence that the process improves stu-dent learning and that it helps the school to prepare for future challenges in business education). We find this outcome both logical and intuitively appealing. The relevant administrative questions therefore become, to what extent are we supporting the AOL process with adequate resources and what evidence are we collecting and disseminating that the AOL process is improving the educational experience of our students. Be-cause the purpose of the latter is to help energize faculty with regard to the process we encourage multiple forms of direct and indirect measurement followed by the purposeful dissemination of information.

The results on energy and level of faculty involvement, and the responses to the open-ended questions in the survey, clearly indicate that many schools are continuing to strug-gle with faculty ownership of the AOL process. The number one challenge continues to be related to faculty time, in-centives and commitment. Motivating and engaging faculty where faculty are experiencing assessment fatigue, where there are few direct rewards, and in the face of powerful institutional and market disincentives, is a difficult chal-lenge. To the extent that AOL processes can be structured in such a way as to more efficiently utilize faculty resources in the process, faculty fatigue may be minimized. For ex-ample, it may be the case that institutions devote so much time and attention to measuring and assessing that there is little energy or time remaining for closing the loop and follow-up.

However, it may be that a certain level of faculty resis-tance based on overload and lack of adequate incentives is inevitable, and that schools need to focus on other drivers of faculty engagement, including intrinsic incentives. The survey results suggest that faculty must have a baseline knowledge concerning AOL expectations and assessment methodologies. But more importantly, faculty must be con-vinced that AOL will result in meaningful improvement in student learning. Faculty are concerned about the value of the educational experience, and they are energized and motivated to participate in that process if it is useful and prepares students for the future. How to demonstrate the effectiveness of AOL is not entirely clear, but continuous sharing of AOL results, particularly closing the loop actions,

and celebrating successes should be part of this process of persuasion.

A previous study (Rexeisen & Garrison, 2013) reported that there are difficulties in implementing CTL systems. For example, it is taking on average over four years to evaluate the impact of a CTL action. Schools need to understand that closing the loop is not only the final, critical stage in the AOL process, but that doing it effectively may have a positive impact on faculty ownership. With regard to the long feedback loop in the CTL process we encourage exploration of strategies to accelerate the assessment process, including piloting of CTL interventions.

It is interesting to observe that one of the factors differen-tiating schools that are energized from those that are not is whether the faculty believe that the AOL process is helping to prepare their school for future challenges. In other words, not only that students are learning better but also that the differences are meaningful and the AOL process is helping schools to identify and respond to future educational chal-lenges. In this vein we applaud AACSB’s reconsideration of the merits of indirect measures of AOL outcomes as we think it may contribute to helping schools assess future needs and therefore feel more confident in the overall AOL process. Our findings also lend support to AACSB’s most recent changes that will tighten the integration of AOL within curriculum management as a means of encouraging innovative curric-ular enhancements that are responsive to evolving market dynamics (AACSB, 2012).

Another challenge that schools have identified is the sus-tainability of AOL systems. Sussus-tainability requires adequate resources dedicated to assessment to assure continuity of the effort over time. Discussion of AOL results on a reg-ular basis, holding intensive training workshops, and an-nual assessment retreats are other methods schools use to enhance faculty engagement and develop a culture of con-tinuous improvement. Our results suggest that a sustainable AOL process must be (a) clear and easy to understand, (b) well organized with effective processes, (c) provide evidence that resources are properly aligned to direct the time and attention of faculty to appropriate AOL activities, and (d) continually demonstrate the value of the process to improv-ing student education so as to energize faculty in the long run.

Finally, we encourage further conversation within AACSB and the literature concerning the definition of faculty ownership. Is it, for example, necessary to have all faculty members engaged in the process or can a strong nucleus of dedicated faculty advance collegial interests if housed within a supportive and reasonably informed general faculty? If we more thoroughly engage employers in the AOL process can we address faculty concerns and demonstrate the value of assessing student learning (and showcase students) to this important constituency? We also encourage more research into and discussion about how business schools can more quickly assess the impact of proposed curricular changes.

FACULTY OWNERSHIP OF THE ASSURANCE OF LEARNING PROCESS 89

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1988).Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago, IL: Dorsey Press.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2012).

Exposure draft standards. International eligibility procedures and ac-creditation standards for business acac-creditation. Retrieved from https:// higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AACSB/AACSB%20BRC%20 Exposure%20Draft%20Standards%20-%2014%20September%202012. pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJH5D4I4FWRALBOUA&Expires=134 8409757&Signature=TgxZW%2FIpscdR5VbW%2BdSCs4HfwNs%3D Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2013).

International eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for busi-ness accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/accreditation/ business/standards/2013/2013-business-standards.pdf

Brocker, J. L. (2007).Involving faculty in assessment activities associated with AACSB assurance of learning standards. (Unpublished doctoral dis-sertation). University of Denver, Denver, CO.

Kelly, C., Tong, P., & Choi, B.-J. (2010). A review of assessment of student learning programs at AACSB schools: A dean’s perspective.Journal of Education for Business,85, 299–306.

Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools making the grade.Journal of Education for Business,82, 189–195.

O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors.Quality and Quantity,41, 673–690.

Pringle, C., & Michel, M. (2007). Assessment practices in AACSB accred-ited business schools.Journal of Education for Business,82, 202–211. Rexeisen, R. J., & Garrison, M. (2013). Closing-the-loop in assurance of

learning programs: Current practices and future challenges.Journal of Education for Business,88, 280–285.