THE FAMILIAR

MADE STRANGE

AM E R I CA N I CO N S A N D A RT I FAC TS

A FTE R TH E T RA N S N AT I O N A L TU R N

E D I T E D B Y B R O O K E l . B L O W E R

A N D M A R K P H I L I P B R A D L E Y

124 NICK CULLATHER

revised trade rules, the New International Economic Order (NIEO), which would ban tariff protecions and subsidies and allow naional regulation of multinational corporations. The NIEO would allow the planned industri alization of the Third Wold, but the United States and Europe responded . with a strategy to shrink the state and deregulate Third Wold markets. .S. government spending fueled high-tech industries and modern agricultue, but any attempt by Kenya or Bolivia to follow the same policy was, accord ing to Pesident Ronald Reagan, ''cheating."34 The Wold Bank enforced the new development orthodoxy, known as neoliberalism.

The lamour of the jet-seting economist faded too. In 1966, Rampars magazine eposed Michigan State's economic mission to Saigon as a front for the CIA. 35 The quest for ited growth came under attack by environ mentaliss, and by the 1970s, economists erected ther ambiions toward the moe modest goals of sustainable development. Today international aid focuses on emergency elief, rather than on building industries in poor nations. In the 1980s, a new type of international development celebrity emerged, personiied irst by concert promoter Bob Geldof, and later by U2's lead singer, entepre neur, and acivist, Bono. In making mself the face of humanitarian elief to Mrica,Bono culivated an image of his working-class Dublin roots while at the same ime pushing a pro-business neoliberal agenda for the poorest naions. 36

The modernization schemes that appear in recent Hollywood movies also come with a neoliberl moral. Salmon Fishing in the emen (2011) is a buddy movie pairing a siff British isheries expert with an eccenric sheikh. Their impractical project, to build a ish hatchery in the midle of the desert, is propelled by oil money and W hitehall's need for a feel-good story, "some thing about the Middle East that doesn't involve eplosions." The loss of 1960s optimism is cleaest, however, in he Girl in the Cqfe (2005), a remake of hat Touch of Mink without the mink. Bill Nighy in the Cary Grant role is a sallow civil servant in a top ministerial position earned by a lifetime of cringing. He meets a barista, Kelly MacDonald, who seems equally timid at irst, but when he rashly invites her to the G-8 summit in Reykjavik she inds her inner spunk. Disgusted by the penny-pinching maneuvers of the wealthy nations, she shames them into adopting the Millennium Development Goals. On the surface, MacDonald esembles Doris Day, the working-class con science of the afluent North. In her neoliberal vision, she sees development as a handout the affluent wold can, out of a sense of charity, choose to give. Day had a far moe ambitious vision, for a world whee all peoples had the esources to raise their own standards of living. They were already there, waiting to be tapped.

C H A PTE R 10

The Imigration Reform Act of

1965

}ESSE HOFFVNG-GRSKOF

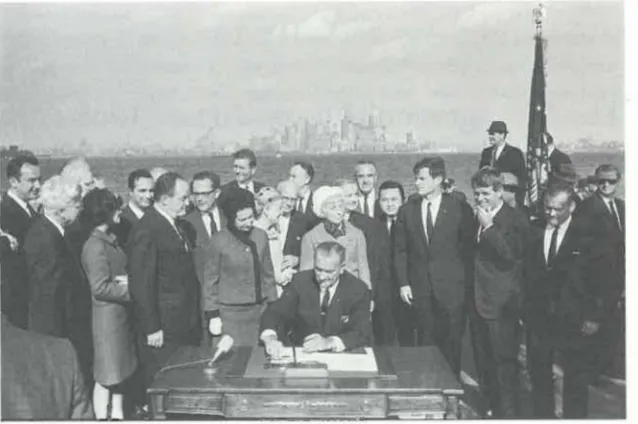

On October 3, 1965, Pesident Lyndon Johnson gaheed eporters and photogaphers to he foot of the Statue of Libert. Thee he sined a ecenly passed law "to Amend the Immigaion and Naionality Act," moe commonly known as he Immigraion Reform Act of 1965. Johnson told the cowd that he counted the eforms among the most important policies enacted by his asraion. The act inally emoved, he said, the shadow of discriminaion that had long haunted "America's ates." Historians have tended to agee. The document Johnson sined almost immediately became an iconic text. It coninues, moe than ifty es later, to occupy a cenal place in nearly eery account of late twenieth-century United States histor. 1

126 JESSE HOFFNUNG·GARSKOF

FIGURE 19. President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration Reform Act, October 3, 1965. LBJ Ubrary photo by Yoichi Okamoto.

inunigrants were racially and culturally preferable to others. The 1965 act ended the quota system, putting in its place a cap of 170,000 inunigrant visas for the Eastern Hemisphee and establishing peferences for appicants with family already living in the United States and for those with special training or skills. Presuming that they were admissible and satisied the established preferences, inuigrants from all countries in the hemisphee were teated equally, on a irst-come, irst-served basis, up to a maimum of 20,000 for each countr. The act also newly imposed a limit of 120,000, and new Labor Department certiication equirements, on Western Hemisphere immigra tion, which had never been subject to limits under the old quota system. 2

The classic account of these reforms has three key elements. First, it por trays the act, as Johnson himself described it, as the end of the era of ii graion restriction and a victory for liberal attitUdes toward immigration and race. As one college textbook puts it, "Taken together, the civil rights revolu tion and inunigration reform marked the triumph of a pluralist conception of Americanism."3 Second, the classic account presents the act as the beginning point, spark, or trigger of a new era of mass immigration to the United States. In 1970 (two years after the act was fully implemented), persons born abroad constituted only 4.6 percent of the U.S. populaion (9.6 mllion people). By 2010 the foeign-born population had risen to 12.9 percent (about 40 mil lion people). Third, the classic view of the act suggests that the end of the

THE IMMIGRATION REFORM ACT OF 1965 127

quota system signiicantly changed the source of immigration to the United States. As one high school textbook puts it, "The act triggered a new wave of inunigration to the United States from Asian and Latin American naions which has alteed the cultural x in the United States."4 Again, the igures are dramaic. In 1960, thee-fourths of the foeign-born populaion in the United States had been born in Europe. By 1990, 62 percent of the foreign born population had been born in Asia or Latin America, and in 2010 this igue had risen to 81 percent.5

128 JESSE HOFF N U N G·GARSKOF

2,000

1,800

1,200

200

Etc:t ot 1 iJ Itnmi;rat[tm Act

1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

FIGURE 20. U.S. immigrant admissions and adjustments On thousands), 1955-2000. These fig ures show that immigration grew fairly consistently from the 1950s through 1990, with only a few minor spikes produced by refugee crises. The most significant legislative act driving the late-century migrant boom was the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which adjusted millions of undocumented residents to the status of lawful permanent residents. Reforms passed in 1990 sig nificantly raised worldwide limits on immigrant visas. Source: Yearbooks of Immigration Statistics (INS, UCIS) 1955-2000.

and popular media eproduce this framing (without the caveats) through the ubiquitous phrase "post-1965 immigration."

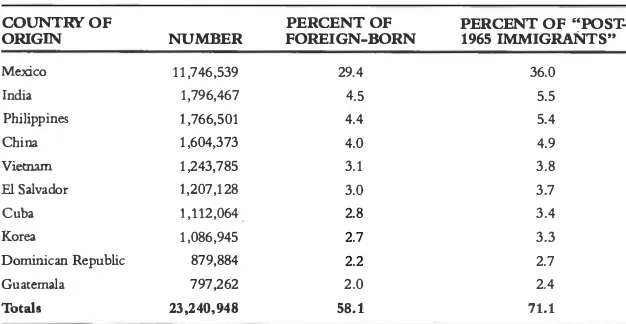

Beyond these historical inaccuracies, the idea that 1965 is the most impor tant signpost for understanding late-century immigration places a very nar row, and largely misleading, naionlist frame around a set of processes that were inheendy transnational. This essay pesents an alternative, transnational framing of late-century immigration based on a brief analysis of each of the ten largest immigraion lows into the United States in the period. Together these ten cases account for about 58.1 percent of all immigrants and about 71 percent of Latin American, Caribbean, and Asian immigrants (that is, a large majority of those newcomers most fequendy referred to as post-1965 immigrants) in the period (see table 1). I use the word "transnaional" not to emphasize the cultural, poliical, kinship, and economic ies that many immi grants build across naional boundaries. I mean rather to suggest that histo rians should seek to understand and epesent immigraion as a consequence

THE IMMIGRATION R EFORM ACT OF 1965 129

of relationships between the United States and particular other parts of the world, and as a constituent part of some of those relaionships. This trans national model ovelaps signiicandy with the idea, eloquendy proposed by scholars including George Sanchez and Nina Glick Schiller since the 1990s, that imperialism is the crucial missing piece in most accounts of .S. immigration. Put succincdy, most of the societies that most proliically sent immigrants to the United States after mid-century not only had deep and intimate ties with the United States; they wee primary targets or principal adversaries of .S. imperial power as it was efashioned during the lobal conflict with the Soviet Union and China that lasted roughly from 1945 to 1991 (the Cold War). 9

To see how this approach can evise our thinking about the 1965 act, let us start with the Philippines. The Philippines sent 3,100 immigrants to the United States in the last year before the passage of the 1965 act. W ithin two ears of the act's full implementation, that number rose to 31,000. This would seem to make the Philippines a fairly convincing case of "post-1965" immigraion. But specialists in this aea have long argued that it is actually better seen as a case of "post-1898" immigraion, highlihting the long-term consequences of .S. power in the Philippines for understanding immigra tion seams. There is something to this, and not just for the case of the Philippines. Beginning in 1898, the United States occupied and governed, for varying lengths of time, the Philippines, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Nicaragua, while making several military interventions in Meico and Honduras and brokering the independence of Panama from Colombia.

able 1

Top ten sending counries

n 2010.OTY OF PERCET OF

OIGN UBER FOEIGN-BORN

Meico 11,746,539 29.4

India 1,796,467 4.5

Philippines 1,766,501 4.4

China 1,604,373 4.0

Viem 1,243,785 3.1

l Salvador 1,207,128 3.0

Cuba 1,112,064 2.8

Korea 1,086,945 2.7

Dominican Republic 879,884 2.2

Guatemala 797,262 2.0

Totls 23,240,948 58.1

PERCET OF "POST-1965 IMIGANTS"

36.0 5.5 5.4 4.9 3.8 3.7 3.4 3.3 2.7 2.4 71.1

130 JESSE HOFFNUNG·GARSKOF

In the same period, the United States took permanent possession of Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Hawaii, American Samoa, and other outlying island territories. Like their British and Fench counterparts in Asia and Africa, U.S. companies and colonial oficials organized large-scale migra- . tion from place to place within this growing empire (Filipinos to Hawaii, Puerto Ricans to the Canal Zone, Haitians to Cuba). By the 1920s, patterns of colonial recruitment also brought colon.fsubjects to the mainland, espe-. cially Puerto Ricans and Filipinosespe-. Mexican workers, though not formally

colonized, moved from areas of expaning U.S. influence in Meico to agri cultural and mining enclaves in the U.S. Southwest that closely resembled colonial work camps. This tradition of labor recruitment from territories that lay within the orbit of U.S. imperial power grew eponentially during and immediately after World War II. The Bracero Program and other con tract labor schemes brought in more than 4 million workers from Meico, 420,000 from Puerto Rico, and 100,000 from the Briish-controlled Carib bean, helping to establish pioneer comunities, �ecruinent networks, and economic and cultural systems based on the outmigration of family or com munity members in each of these areas. 10

But it was during the Cold War that most of the countries and territories that had experienced U.S. occupation after 1898 became large-scle immigrant sending societies. The Philippines is a cse in point. Filipinos, living under U.S. colonial goverment, had been ecruited as laboers and shipped to Hawaii and California in the 1910s and 1920s. But the 1934 bill that promised eventual independence to the Phlippines eclassiied Filipinos as "inadmissible aliens;' a status ready applied to other persons from Asia and the Pacific islands. The 1952 Immigration and Naturlizaion Act (passed at the height of the Korean War) removed the clause making Asians inadmissible but estricted immigra ion from the Philippines to a quota of 100 per year. However, as policy makers in Washington souht to exert inceasing power in the Pacific under the new rubric of the Cold War, they maintained thee permanent mlitary bases and a major civilian pesence in the Philippines. The United States also distributed military and development aid to the Philippine government in an effort to secue the alliance and preserve the privileged posiion enjoyed by U.S. business inteess thee. This led to a significant migration stream from the Philippines outside of the quota system. For instance, the United States continued, after independence, to ecruit Filipinos diecly from the former colony into the U.S. Na. Moe than 27,000 Filipino naionals served in the navy between the beginning of the Korean War and the end of the Vienam War. About two-thirds wee ecruited befoe the end of the naional origins quota system. These veterans eventually qualified for naturalizaion and began to bring their

THE IMMIGRATIO N REFORM ACT OF 1965 131

families to the United States. U.S. servicemen and civilians of non-Filipino ancestry who married Filipinos while staioned in the Philippines did the same. Between 1955 and 1965, more than 24,000 Filipino immigrants enteed the United States as imediate family members of .S. citizens. Over this decade, the United States also brought 11,000 Filipino nurses to U.S. hospitals s exchange workers and trainees.U

Through military recruitment, development aid, and exchange programs the U.S. government hoped to expand the class of Enlish-speaking, U.S. oriented Filipino elites that had first emerged under U.S. administration. These programs also created a "culture of migration," both a pioneer com munity of settlers in the United States and a set of "narratives about the promise of immigration to the United States" circulated by media, recruiters, and by the U.S. government, as well as by immigrants theselves.12 Thus when Congress eliminated the quota system, large numbers of Filipinos already wanted to come to the United States, and many thousands had the means to make use of the two preference categories (despite the fact that Congress hoped these peferences would limit new immigration from Asia): professional and family ties to the United States. W hat is signiicant about the 1965 act is not that it sparked immigration from the Philippines, but rather that it expanded the opportunities available to a network of migrants that had already begun to form as the Cold War reshaped the long colonial rela tionship with the United States.13 Adding a caveat to the classic account, that the 1965 act unintentionally inceased immigration from Asia through family peferences, does not comunicate the transnational dynamic that made this unintended consequence possible.

132 J E S S E HOFFNUNG·GARSKOF

end of this experience of "exclusion" in the late twentieth century was not only a growing numbers of immigrants, but also a shift in racial ideology and racial practices. Chinese people, long sinled out as uniquely unsuited for American ciizenship, came to be understood as uniquely assimilative and economically successful. But 1965 was not the turning point for this change. In fact the shift began in the 1940s, as China became an inceasinly important strategic site in both the conflict

ih

Japan and the emerging global competition with the Soviet Union. The United States repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. The United States also set up exchange programs for Chinese university students and intellectuals, in the hopes of building ties with the Naionalist movement and epanding .S. inluence in the region.14 In 1946 (with moe than 100,000 .S. troops stationed in China) Congress made the Chinese wives of .S. ciizens and legally admit ted Chinese immigrants eligible to immigrate, without regard to quotas. Almost 17,000 Chinese imigrants came as spouses of .S. citizens in the decade before the 1965 act went into effect. 15Then in 1949, the "loss" of mainland China produced a migratory crisis similar to later experiences in Havana, Saigon, and Tehran. The .S. consulate in Hong Kong received a sudden influx of 100,000 applications for admis sion. Unable to apply for immigrant status because of the quota system, these refugees availed themselves of the existing structure for gaining entry to the United States. They presented themselves as .S. citizens or close relatives of .S. citizens, though the consul believed that many of these relaionships wee falsiied. The victory of the Communist Party in mainland China also stranded a cohort of Chinese exchange students with Nationalist political leanings. In response, the .S. government used refugee policy to admit the stranded students and a total of about 25,000 highly skilled Chinese workers outside he quota system between 1953 and 1965. The Jusice Deparment also began a "confession" program for Chinese who were in the country based on false documentation, regularizing 30,000 people as legal immigrants in the 1950s. This allowed Chinese American families to create legitimate documentation of their actual family relationships in place of the elaborate system of false paper family ties. 16

These factors explain why the family preferences, included in 1965 with the epressed intent to exclude Chinese immigrants, actually facilitated a massive increase in Chinese immigraion. As in the Filipino case, in 1965 a large pool of Chinese families had ecendy emigrated to the United States and were therefoe poised to make use of measues· allowing for reuniica tion with close family overseas. Another group was ecently regularized, free from the strictues of "paper" family relationships, and uniquely poised to

THE IMMIGRATIO N R EFORM ACT OF 1965 133

begin a new process of reuniicaion with their actual family members liv ing overseas. W hen the 1965 act, conrary to epectation, did dramaically incease Chinese immigration, there was litde public outcr. The Cold War efugee program and sympathetic coverage of Chinese family reunification had already begun to shift popular seniment tward a view of Chinese immigrants as highly educated people with legitimate families, as allies of the West, and fully capable of rapid assimilaion into the .S. middle class: a model minorit. 17

The Cold War lso helps eplain the very rapid rise of Koean immigra ion near the end of the centur. Although Koea had not been a traditional target of .S. imperial power previous to mid-century, .S. involvement in the Korean War· (an effort to contain Soviet and Chinese inluence in Asia) led to an era of close military and economic cooperation between the South Korean dictatorship and the .S. government, and to attempts to integrate key sectors of the Koean population into the orbit of the United States through educaional exchanges, cultural exchange, and spreading consumer capitalism. Because South Koea was never "lost," there was no efugee crisis like the one that emerged in Hong Kong in 1949. Yet Koean immigrants, like Chinese, experienced a radical reconiguring of the racial exclusions they had long faced in the context of new ways of dividing the wold into friend and enemy during the Cold War. Media accounts of Koreans began to con strue them as racially acceptable allies, vicims to be rescued from Commu nist aggression. Perhaps nowhee was the emerging idea that Koreans were racially suited to becoming Americans more visible than in the rapid rise in adoption of Koean babies by white citizens of the United States (beginning in the aftermath of the war and growing to constitute nearly 60 percent of all oerseas adoptions by the mid 1970s). Adopted babies, however, did not make use of family uniicaion prefeences, so this did not lead to a broader growth in Koean immigraion. The Korean spouses of .S. service person nel staioned in South Korea, on the other hand, became links in family-based chain migrations as the new law made it possible to bring paents and sib lings of citizens, and immediate relatives of immigrants, to the United States. Meanwhile, South Koea developed a class system in which foeign educa tion in English became one of the most important ways to secure pefeen tial employment. Eventuall, student exchange and professional peferences became an avenue for immigration, as many Koreans shifted their status from exchange visitor to immigrant. 18

134 JESSE HOFFNUN G-GARSKOF

inteests in Cuba in the 1830s. The U.S. military occupied the island in 1898 and again in 1906. By the 1950s a major low of tourists, cultural profes sionals, and business visitors moved in both direcions between Cuba and the United States, and a steadily growing steam of immigrants moved to the United States from Cuba. South Vietnam was more like South Korea, the site of a new effort by U.S. irms and government representatives to integrate local elites into a sphee of U.S. influence afte

;

-o

rld War II, and especially during the Vietnam War. Vietnamese immigration to the United States was a minor part of this new relationship, showing only modest growth even after the 1965 reforms. The victories of Cuba's Twenty-Sith of July move ment in 1959 and of the North-Vietnamese army in 1975 produced migrant waves from both countries that, especially at irst, skewed toward precisely the urban elites who had been most closely linked with U.S. irms and ofi cials. In both cases, the U.S. foreign policy interests as well as humanitarian impulses led to a speedy recognition of the efugee status of these migrants. Under U.S. law, "refugee;' a legal concept that emerged to refer to stateless people after Wold War II, became a blanket term eferring to all immigrants from Cuba, Indochina, the Soviet Union, and (in smaller numbers) other enemy states during the Cold War and its immediate aftermath. Immigrants from these selected countries did not have to demonstrate speciic instances of oppression or persecution; merely desiring to leave a Communist polity was grounds for humanitarian relief. Legislation passed in 1966, 1977, and 1980 allowed millions of asylum seekers and refugees from these countries to adjust their status to that of immigrant, independent of the numerical limits, preference systems, and even some of the admissibility requirements imposed by the 1965 act (see igure 20). These were Cold War immigrants, but deinitely not post-1965 immigrants.19Like Cuba and the Philippines, the Dominican Republic had a "post-1898" relationship with the United States, which had militarily occupied the epublic from 1916 to 1924. But only small numbers of relatively well-off Dominicans raveled to the United States befoe 1961, when Santo Domingo experienced its own Cold War refugee crisis. In the wake of the assassination of dictator Rafael Trujillo, thousands of Dominicans sought U.S. visas, the only pracical way to leave the countr. This created an immediate backlog in the processing of applications. Trujillo's death came close on the heels of the "loss" of Cuba and only weeks after the Bay of Pigs debacle. It was thus very uncomfortable for the Kennedy administration when; in 1962, frustrated visa seekers joined protests and riots outside the consulate. The U.S. govern ment responded by building two new modern consulates and sending in a "planeload" of visa oficers to the Dominican Republic (as well as the Peace

TH E IMMIGRATIO N REFORM ACT OF 1965 135

Corps). Immigraion shot up from a few hundred a year to nearly 10,000 a year by 1963, and to more than 16,000 in 1965, when U.S. Marines invaded the Dominican Republic to prevent a victory by center-left forces in an emerging civil war. Mter the United States helped install a new right-wing authoritarian regime, the State Department remained acutely concerned that any interruption in the flow of visas could beed resentment of the United States. Yet because the regime in Santo Domingo s a U.S. ally, U.S. immi gration oficials did not teat migrants leeing the Dominican Republic in these years as efugees unless they could prove spec

i

ic experiences of per secution. Dominican migration, though encouraged by .S. foreign policy, faced increasing restriction under immigration policy after the reforms of 1965. As a esult many Dominican immigrants settled in the United States through the use of family euniication exemptions, by overstaying tourist visas, or through the dangerous open-boat voyages to Puerto Rico. 20136 JESSE HOFFNUN G-GARSKOF

the period, the United States denied the vast majority of peiions for asylum by Salvadorans and Guatemalans. The oficial foreign policy of the Reagan and Bush administraions denied or excused state violence and genocide in Central America, and immigration policy followed suit. The irst wave of. about 300,000 Guatemalan and Salvadoran asylum seekers was unable to regularize to the status of legal immigrant unil the early 2000s. Meanwhile, growing numbers of Central Americans used mig;ation to the United States Qargely by means of entry without inspection over the Meican border) as a strategy for coping with economic hardship, during both the wars and the economic adjustments that followed.22

Cold War migration thus provides a �ompelling framework for explaining the "trigger" in eight of the ten leading migration lows of the late twentieth century. It does not work paricularly well, however, for the cases of Mexico and India. As we have seen, Meican immigration roughly its the model of a "post-1898" immigration. But it is really a case ll to itself. The epansion of U.S. inluence and capitl investment (1876-1930s) eshaped the Mei can economy around the export of primary products into the U.S. market. This created a migrant workforce that moved seasonally and cycliclly into pockets of industrial agriculture and mining on both sides of the border. This low increased dramatically in the 1920s, at the moment of new restrictions on European immigration, only to be cut short by a massive repatriation campaign during the Geat Depression. 23

The movement of migrants across the U.S.-Meico border began to grow again with the creaion of the Bracero Program in 1942. Until it s phased out in 1968, the program provided legal status, if not siniicant labor rights, to about 450,000 Meicans each year. Most wee male workers who crossed the border at their own expense and without inspecion by U.S. authorities. Most worked in the booming agricultural industries of the Souhwest. Most even tually eturned to Mexico in a pattern known as circular migraion. Migra tion became a crucial part of the cultul and economic systems of sending communities in Meico and of eceiving communities in the United States. Employers in these industries continued recruiting Meican workers without interruption after the cancellation of the Bracero Program. As a esult about 27 million Meicans enteed the United States without inspecion between 1965 and 1986. This s about the same number, each year, as· had enteed without inspecion annually during the Bracero Program. But U.S. immi gration officials no longer rounded up those who entered without visas and

delivered them to employers as guest workers. Now immigraion oficials treated them as "deportable aliens." Appehensios of deportable aliens thee fore rose steadily in the 1970s, spurring media and political igues to decry an

TH E IMMIGRATIO N REFORM ACT OF 1965 137

immigration crisis and spurring the implementation of inceasingly estrictive and punitive border enforcement measures. This made it more dificult to move back and forth to Meico seasonall, and led to a growing long-term undocumented populaion, alongside the 1.3 million legal immigrants who entered from Meico between 1955 and 1980. In 1980, the Census bureau counted 2.2 million persons born in Meico living in th�United States, about 15.6 percent of the foein-born.24

138 JESSE HOFFNUNG-GARSKOF

average of half a million people crossed legally from Meico into the United States each day to transport goods, to work, shop, visit family, get health cae, or attend school. W ithout this context, it is dificult to fully understand the much smaller number of unauthorized crossings in the period.25

The legal context for Mexican migrants inside the United States lso changed dramatically after 1986, with the passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act. Though the Reagan administrationpesented IRCA as an effort to resolve a perceived crisis of unauthorized entry, the reforms actually facilitated the boom in both legal and illegal immigration in the 1990s and beyond. W hile imposing employer sanctions, and adding to the mounting security apparatus at the border, IR CA included an amnesty provision that allowed the legalization of 3 million people, 2.3 million of them Mexican. Once protected by legal residency, this population began to move out of a very high concentration of work in agricult4re toward urban labor in service, construction, and manufacturing sectors, and out of California and Texas into other states. Newly regularized residents made use of family uniicaion provisions to help relaives move to the United States legall. They also pro vided the social netWork and resources for the major wave of unauthorized imigrants that entered in the wake of GATT and NAFTA. The post-1986 wave, legal and unauthorized, brought large numbers of women and children into Meican migrant communities that were peviously overwhelingly male. By 2000, Mexican immigrants of varying legal status counted for three out of every ten foreign-born persons in the United States and formed part of the low-wage workforce in nearly every corner of the United States.26 During the 1990s, similar restructuring programs, W TO membership, and trade agreements took the place of Cold War conflicts in governing relations between the United States and Central America, the Caribbean, and parts of South America. A hemispheric trade and producion system built on the elimination of social spending and the close integration of economies with drastically different income levels and wage scales became· the key transna tional context for post-Cold War immigration from the region.

The case of Indian immigraion also points stronly to lobal economic restructuring as a framework for understanding post-Cold War immigraion patterns from Asia. Indian immigration s not linked signicandy to U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War. It arose rather out of the patterns of igraion established under British colonial rule and in response to the new conditions generated by decolonization. India, newly independent, began to send mllions of emigrants abroad to the

K

and former British colonies in the 1950s. The 1965 act opened the United States to a portion of this growing diaspora. Uike Chinese, South Korean, and Filipino immigrants after 1965,TH E IMMIGRATIO N REFORM ACT OF 1965 139

Indian imigrants had few eising ties to the United States. W hile those other groups depended heavily on family uniication peferences, or refugee and exchange programs, in combination with professional preferences, Indians were unique in ceating a pioneer generation of immigrants almost exclusively throuh the preference system for highly skilled workers. Indian migrants thus became the model for the eforms Congress imposed in 1990� This law raised the total oldwide cap on immigrant visas while shifing peferences to be less favorable to family reuniication and more favorable to employment based immigration. The law also paved the way for the dramatic epansion of the guest worker program for nonagricultural workers.

Employers in the United States successfully advocated for these changes as Korea, India, Taiwan, and, most notably, China ceated new development models based (like Mexico's) on exports to Western markets, while dramati cally expanding their university systems and the supply of highly trained pro fessionals. In such a context, corporations with an increasinly lobal each, as well as U.S. universities and hospitals (long accustomed to incorporating Filipino nurses, Korean students, and Indian doctors and engineers) were as eager to integrate the growing number of Asian professionals and managers into a lexible high-skill global workforce, and to dip into the global market for contingent middle-income and low-wage workers, as they were to relo cate factories to Mexico or call centers to India. This drove a rapid increase in the number of temporary, nonimmigrant visas (including temporary work ers, intercompany transfers, students, and exchange visitors). Nonimmigrant work or exchange visas outnumbered immigrant visas by the end of the 1990s. U.S. employers drew increasingly on migrants with contingent legal status and migrants entering without inspection to exert pressure on the middle and lower rungs of the U.S. labor market. The complex process of lobal restructuring, what has often been called "lobalization,'' including signiicant changes in the nature of employment in the United States, is thus the key context for understanding the dramatic boom in migrations of both high- and low-skilled workers to the United States after 1990.27

140 JESSE HOFFNUNG-GARSKOF

as soon as the act was passed, the baseline for the classic division of U.S. imigraion history into pre-1965 and post-1965 periods. Immigration laws,.

including many provisions established by the 1965 eforms, are undoubt edly crucial to understanding immigrant flows. Yet building our neline of immigration history around the 1965 act narrowly frames the issue of late century immigraion around he quesion of whom Congess decided to admit. It eturns us to the idea of the UnitedStates as a uniquely welcoming "naion of immigrants" while hiding from view ransnational and imperial relationships and the lobal contexts that ae essential for understanding why and how late-century migrant streams actualy took shape. This narrow view einforces a noion, too common in our public debates, that the desie of the wold's people to come to the United States is self-evident, not in need of explanaion. It facilitates the idea that contemporary immigration is meely a collecion of millions of discrete decisions by individual immigrants to "seek a better life" by becoming "American." And, in an ironic twist, it fuels the arguments of the most recent crop of ani-immigrant politicians who charge, for instance, that "thanks to Teddy Kennedy's 1965 immigration law, we no longer favor skilled workers from developed nations, but instead favor unskilled immigrants from the Third World."28

A brief analysis of the top ten immigrant flows in the United States since the 1960s suggests that the idea of 1965 as the primary turning point in late-century immigration history gets the story wrong. I suggest that a division into "Cold War" and "post-Cold War" immigration, with some special attention to the unique and singularly important case of Mexico, is a much better way to organize our understanding of late-century migra tions. The idea is not merely to reframe immigration history around foreign policy or global sructural change, but rather to point to the interplay among imigration policy, foreign policy, and asyminetrical international exchange as an eplanation for the timing and shape of new immigrant lows. The story begins not with the opening of the Golden Door to the hazily undif feentiated peoples of the Third World, but with the ways that the United States, building on its history of imperial enterprise, exerted power abroad and extracted disproportionate beneits in the context of the Cold ar and its aftermath. The story starts not with the arrival of new immigrants on U.S. shores, but with the mechanisms by which people in some parts of the world, with speciic histories of interaction with the United States, began to imagine moving to the United States. And the story does not proceed as a simple process of doing away with racial exclusions, but examines the s that elements of U.S. foreign, industrial, commercial, and immigraion policy worked together, or sometimes at odds, to encourage, celebrate, discipline, or

C H A P T E R 1 1

President Jimy Carter's

Inaugurl Address

MK PHIIP BDLEY

"The American eam endures," Pesident Jimmy Carter told he American people in his inaugual address on January 20, 1977. "We must have faith in our country-and in one another . . . . Let our ecent mistakes bring a esurgent commiment to the basic principles of our naion, for we know

f

we despise our own overnment we hae no fute." Dawing on the words of the Hebrew prophet Micah, Carter asked Americans o renew "our search for humility, mercy and jusice."1 Carter's seventeen minute address, short by inaugual standards, was deliveed in a "homileic style and moralisic tone" that appeared to offer "a therapeutic moment of tanquiiy" for the naion after the taumatic faled war in Vietnam upended comfortable Cold War veriies and after the Watergate scandal, evelaions about Pesident Richad Nixon's abuses of eecuive poer and then ignoble esinaion, unleashed a crisis of conidence in the American state. 2 With the formal inaugural ceremony completed, Carter further signaled his break from the Nixonian imperial pesidency by jumping out of his bulleproof limousine and lking with wife Rosalynn and nine-year-old daughter Amy the mile and a half from Capitol Hill to the White House, the irst pesident ever to do so. " People walking along the paade route;' Carter recorded in his diar, "when they saw that we wee ng, bean to cheer and to weep."3192 NOTES TO PAG E S 1 1 4 - 1 2 0

of Power and the Road to �r in Vietnam (Berkeley: Un iversity of C aliforn i a Pess, 2005), 1 65-79.

17. LBJ-Bun d y telcon , September 8, 1964, in Mich ael Beschloss, ed ., Reaching for

Gloy: Lyndon Johnsons Secret hite House Tapes, 196-1965 (New York: Simon &

Schuster, 2001), 35-36; LBJ-Russell telcon , M arch 6, 1965, ibid ., 21}-13.

9.

hat Touch of

Mink1. Delbert M an n , d ir., hat Touch of Mink, Un ivers al, 1962.

2. Terry Melcher, "The Doris Dy I now'' Good Housekeping, October 1963,91.

3. Bosley Crowther, "M aestro of Sophistic ated Come d y'' New York Times

Magazine, November 18, 1962, 18-130. '

4. "Tun n el of Love at the Metro'' Times of India, M arch S, 1959, 5.

5. Molly H askell, Holding My n in No Man's Land: �men and Men and Film and Feminiss (New York: Oford Uniersity Pess, 1997), 21.

6. John Upd ike, "Suie Ce amcheese Spe aks'' New Yoker, Febru ary 23, 1976, 1 1 1 . Centuy America (New York: H arper Peen ni al, 1992), 474-86.

12. This is n ot in clud in g a n umber of filin s in which d evelopmen t is an explicit "Negro Reserve Oicer Wed s Rusk's D aughter," Lodi News-Sentinel, September 22, 1967, 1 ; "Mixed M arri age Ple ases Sec. Rusk'' Chicago Dfender, September 30,

1967, 31.

16. "Guess hos Coming to Dinner'' Ebony, J an u ary 3, 1968, 562. 17. "Phil an thropoid No. 1''Time,Jui.e 10, 1957, 65.

18. "Doctors of Developmen t," Time, Jun e 26, 1964, 86.

19. John . Kenned y, "Speci al Mess age to Con gess on Foreign Aid '' M arch 22,

1961.

N OTES TO PAG E S 120- 126 193

20. N ation al Security Coun cil, "Un ited St ates Objecves an d Progr ams for N aion al Security'' NSC-68, April 7, 1950, http:/ /goo.gl/KPRtQ.

21. Mich ael E. L ath am, The Right Kind of Revolution (Ith ac a, Y: Corn ell Uni john son / archies. hom/ speeches. hom/ 651 003. asp.

2. United St ates, Amending the Immgration and Nationaliy Act, and for Other ur poses (W ashin gton , DC: Governmen t Prin in g Ofice, 1965), htp:/ /w.leisn eis. com/ con gcomp/ getd oc ?SERIAL-SET- ID= 12662-5+S. rp. 7 48; Un ited St ates, Immi gration and Nationaliy Act, Con feren ce Report on Immigr aion an d N ation ality Act (W ashin gton , DC: Govern men t Prin in g Ofice, 1952), htp:/ /w.leisn exis.com/ con gcomp/getd oc?SER IAL-SET-ID=1 1577+H.rp.2096.

194 NOTES TO PAG ES 1 2 7 - 132

American Academy f Political and Social Science 367 (September 1, 1966): 137-49, doi:10.2307/1034851; Mae M. Ngai, "Oscar Handlin and Imigration Policy

Reform in the 1950s and 1960s," Journal of American Ethnic Histoy 32, no. 3 (Spring

2013) : 62-67. .

4. Edward L. Ayers et al., American Anthem: Reconstruction to the Present (Orlando,

FL: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 2009), R15.

5. Campbell ]. Gibson and Kay Jung, Historical Census Statistis on the Foreign

Bon Population f the United States: 1 850-2000, Population Division Working Paper (Washington, D.C. : U.S. Census Bureau, February 2006), http:/ /ww.census.gov/

population/ww I documention/ twps0081 I twps0081.hml; Elizabeth M. Grieco

et l., he Fore ign-Bon Population in the United States: 2010, American Community Survey Reports (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, May 2012).

6. Mae M. Ngai, Imfossible Subjecs: fllegal Aliens and the Making f Modn Ameica

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004); Erika Lee, At America� Gates:

Chinese Immgration during the Exclusion Era, 1 882-1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

7. See the useful smmary of conversations about this in "Thee Decades of

Mass Immigraion: The Lega�y of the 1965 Iriunigraion Act;' Center for Immigration

Studies, htp:/ /ww.cis.org/1 965ImmigraionAct-Massimmigration.

8. For efugees and immediate relatives see reports and yearbooks of the Immi gration and Naturalization and Immigration and Customs Enforcement Services

(INS Statistical earbooks). For estimates of undocumented immigraion see Douglas

S. Massey and Kaen A. Pen, "Unintended Consequences of US Immigration

Policy: Explaining the Post-1965 Surge from Latin America," Population and Develop

ment Review 38, no. 1 (March 2012): 1-29, doi:10. 1 1 1 1/j.1728-4457.2012.00470.x.

9. George ]. Sanchez, "Race, Naion, and Cultue in Recent Immigraion Studies,"

Journal f American Ethnic Hstory 18,no. 4 Guly 1 , 1999): 66-84,doi:10.2307 /27502471 ;

Nina Glick Schiller, ".S. Immigrans and the Global Narraive," Amerian Anthro

pologist 99, no. 2 (1997): 404--8, doi:10. 1525/aa. 1997.99.2.404; Nina Glick Schil ler, "Tansnaional Social Fields and Imperialism: Bringing a Theory of Power to

Transnaional Studies," Anthropological heoy 5, no. 4 (December 1 , 2005): 439-61,

doi: l 0. 1 177/1463499605059231.

10. Dorothy B. Fujita-Rony, "1898, .S. Militarism, and the Formation of Asian

America;' Asian American Poliy Review 19 (2010): 67-71; Paul A. Kramer, " Power

and Connecion: Imperial Histories of the Uited States in the World," American

Historical Review 1 16, no. 5 December 201 1): 1348-91.

11. United States Navy, Bueau of Naval Personnel, Filipinos in the United States

Navy, October 1 976, http:/ /ww.histo.navy.mil/library/online/llipinos.htm;

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Empire f Care: Nursing and Migration in Filpino American

Histoy (Durham, NC: Duke Uiversity Press, 2003) ; INS, Statistical Yearbooks.

12. Choy, Empire of Care, 4.

13. See also Yen Le Espiritu, Home Bound: Filipino American Lives across Cultures,

Communities, and Countries Berkeley: University of California Pess, 2003).

14. Madeline Y Hsu, "The Disappearance of America's Cold War Chinese Refu

gees, 1 948-1966,"Joual of Amerian Ethnic Histoy 31, no. 4 (2012): 12-33.

1 5. Susan Zeiger, Entangling Alliances: Foreign iir Brides and American Soldiers in

the Twentieth Centuy (New York: U Press, 2010).

N OTES TO PAG ES 1 3 2 - 139 195

16. Mae M. Ngai, "Legacies of Exclusion: Illegal Chinese Iigration during

the Cold War Years," Jounal of American Ethnic History 18, no. 1 (October 1 , 1998):

3-35; Hsu, "Disappearance."

17. Ngai, "Legacies of Exclusion"; Martha Gardner, he Qualities f a Citizen:

omen, Immgration, and Citizenship, 187- 1965 (Princeton,

J:

Princeton University Press, 2009).18. Pyong Gap Min, "The Immigration of Koeans to the United States: A

Review of 45 Year (1965-2009) Trends," Development and Society 40, no. 2 (Decem

ber 201 1): 1 95-223.

19. Louis A. Perez Jr. , On Becoming Cuban: Identi, Nationalit, and Culture (Cha pel Hill: University of North Carolina Pess, 2008); Silvia Pedraza, "Cuba's Refu gees: Manifold Migraions," in Origins and Destinies: Immgation, Race, and Ethnicity in America, ed. Silvia Pedraza and Ruben G. Rumbaut (Cengage Learning, 1996), 26

�

-79; Nhi . Lieu, he American Dream in Vietnamese (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 201 1). For statistics on refugees after 1980 see annual ORR Reports to Congess, http:/ /w.acf.hhs.gov/progras/orr/esource/annual-orr-reports to-congress.20. Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof,A Tale ofTwo Cities: Santo Domingo and New York ter

1950 (Princeton,

J:

Princeton Uversity Press, 2008).21. Geg Grandin, he ast Colonial Massacre: Latin Ameria in the Cold or (Chicago:

Universiy of Chicao Pess, 2004).

22. Susan Bibler Coutin, "Falling Outside: Excavaing the History of Cen

tral American Asylum Seekers," Law & Social Inquiy 36, no. 3 (2011): 569-96,

doi:10. 1 1 1 1 /j. 1 747-4469.201 1 . 01243.x; Maria Cristina Garcia, Seeking Ruge: Cen

tral American Migration to Mexico, the United States, and Canada Berkeley: University of California Pess, 2006).

23. See, for instance, George ]. Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnici,

Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 190-1945 (New York: Oford University

Pess, 1995).

24. Massey and Pen, "Unintended Consequences." Statistics ae an from

Immigration and Naturalization Service Annual Staisical Reports.

25. Stephen Casles and Mark ]. Miller,

e

Age f Mgration: Innational PopuationMoemens in the Moden World (Bstoke, K: Palgrave Maln, 2009); Chris topher Wilson, "Working Together: Economic Ties between the United States and

Meico," Wilson Center, Meico Insitute, htp:/ /w.wlsoncenter.org/publicaion/

woring-together-economic-ies-beteen-the-uited-states-and-meico.

26. Jorge Durand, Douglas S. Massey, and Emilio A. Parrado, "The New Era

of Meican Migraion to the United States," Journal f American Histoy 86, no. 2

(September 1 , 1 999): 5 1 8-36, doi:10.2307/2567043.

27. M. C. Madhavan, "Indian Eigrants: Numbers, Characteristics, and Eco

nomic Impact," Population and Develpment Review 1 1 , no. 3 (September 1, 1 985):

457-81 , doi:10.2307/1973248; Sharla Rudrappa, " Cyber-Coolies and Techno Braceros: Race and Commodification of Indian Information Technology Guest

Workers in the United States," Universiy f San Francisco Law Review 44 (2009/2010):

353; Philip Kretsedemas, "The Liits of Control: Neo-Liberal Policy Priorities and

the US Non-Immigrant Flow," Intenational Migration 50 (2012) : e1e18,doi: 10. 1 1 1 1 /

196 NOTES TO PAG ES 1 4 0 - 1 44

28. John . Kennedy, A Nation f Immgrans (New York: Harper & Row, 1964), i, htp:/ /hdl.handle.net/2027 /mdp.39015035331761; Ngai, "Oscar Hanlin";Ann Coulter, "America Plays Pasy n Immigration Drama," ilkes-Barre Times Leader, April 16, 2006.

11.

Pesident Jimmy carter's Inaugural Address

I would e o k Marilyn Young, Caol Anderson, Barbara ys, Sarah Snyder, and Booe Blower for helpful commens on earlier drafts of s essa.

1 . Inaugural Addess

J

immy Carter, January 20, 1977, htp:/ /w.jimmycarterlibr. gov I documents/ speeches/inaugadd. phtml.

2. James Wooten, "A Moralistic Speech," New York Times, January 21, 1977, 1 ; James Reston, "A Revival Meeing;' New York Times, January 21, 1977, 1 8; Hedrick

Smith, "A Call to the American Spirit," New York Times, January 21, 1977, 1. 3. Jimmy Carter, hite House Diay (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), 10. See lso "Crowd Delighted as Carters Shun Limousine and Walk Home,"

New York Times, January 21, ) 977, 1.

4. Barbara Keys, "Kissinger, Congress and the Origins of Human Rights

Diplo-macy;' Diplomatic History 34, no. 5 (November 2010): 823-51 .

5 . Jimmy Carter, Keping Faith (New York: Bantam Books, 1982), 145. 6. American Public pinion on Human Righs, May 1977. Rerieved August 6, 2013, from the iPOLL Databank, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecicut, http:/ /w.ropercenter.uconn.edu.ezprox.librar. wisc.edu/ data_access/ipoll/ipoll.html.

7. Anthony Lewis, "A Craving for Rights," w York Times, January 3 1 , 1977, 1 6 ; Carter, Keeping Faith, 1 43; Ronald S�eel, "Where the Old Left Meets the New Left: Motherhood, Apple Pie, and Human Rights," New Republic, June

4, 1 977, 1 4.

8. Barbara J. Keys, Reclaiming American Virtue: he Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s (Cambridge, A: Harvard University Pess, 2014), 1. Along with Keys, perspecives on the Carter-era turn to human rights that emphasize the domestic emerge in Sandy Vogelsang, American Dream, Global Nightmare: he Dilemma of U.S. Human Rights Politis (New York: W W Norton, 1980); Gaddis Smith, Moral ity, Reason, and Power: American Diplomacy in the Carter ears (New York: Hill & Wang, 1986); Joshua Muravchik, Uncertain Crusade: jimmy Carter and the Dilemmas of Human Rights Poliy (Lanham, D: Hamilton Press, 1986); David . Forsythe, "Human Rights n U.S. Foeign Policy: Retrospect and Prospect," Political Sdence Quarterly 105, no. 3 (Autumn 1990) : 435-54; Burton I. Kaufman, he Presideny of james Earl Carter (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993); Scott Kaufman, Plans Unraveled: The Foreign Policy of the Carter Administration (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2008), 27-46; and Julian E. Zelizer,jimmy Carter (New York: Times Books, 2010), 61-62.

9. Joe Aragon o Hamilton Jordan, White House memorandum, July 7, 1978,

in Naional Security Archive Electronic Brieing Book No. 391, http:/ /w.gwu. edu/-nsarchiv /NSAEBB/NSAEBB391 I.

10. Elizabeth Dew, "A Reporter at Large: Human Rights," New Yorker, July 18, 1977, 36-61. It is evealing that the index to Jules Whitcover's meticulous 684-page

N OT E S TO PAG ES 1 44 - 1 4 5 197

account of the 1976 pesidenial campaign, Marathon: The Pursuit f the residen, 1972-197 6 (Nw York: Ving, 1977) has no enry for "human rights." In one sign of how little popular attenion was paid to human rights before 1977 n the United States, i POLL contains only one survey quesion on human rights between 1960 and 1976 in its database, in which respondens epessed considerable reservaions about how srongly the United States should put pessue on other countries about hn

rights; see Harris/CCFR Surve

y

of American Public Opinion and .S. Foeign Policy 1974, December 1974. By conrast, fort-one quesions about hn rihts ae in the database for 1977 to 1980, with the numbers of quesions on the issue growing eponentially in subsequent decades. Rerieved August 6, 2013, from the iPOLL Databank, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Con necicut, htp://w. ropercenter. uconn.edu.ezprox.librar. wisc.edu/ data_access/ ipolllipoll.html.1 1. Transcript, "Debate beteen Jimmy Crter and President Gerald Ford on Foein and Defense Issues," October 6, 1976, http:/ /millercenter.org/pesident/ spe:ches/ detail/5538.

12. Jimmy Carter, Addess at Commencement Eercises at he University of Nore Dame, May 22, 1977, htp:/ /w.presidenc.ucsb.edu/wslindex.php?pid= 7552.

13. The siniicance of the human rights moment of the 1940s has receied if fering eatmens in Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the >rla:'Ameria 3 VSion for Human Righs (Cambridge, A: Hrd University Pess, 2005), and Samuel Moyn, he Ast Utopia: Human Righs in Histoy (Cambridge, A: Harvard Unversity Pess, 201 1), chap. 2. I eploe its compleiies in he United States and the Twentieth-Centuy Global Human Righs Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Pess, 2016), chaps. 1-4.

14. Samuel Moyn, "From Aniwar Poliics to Ani-Tortue Poliics," n Aw and War, ed. Doulas Lawrence and Sarah Ausin (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Pess, forthcoming); eys, Reclaiming American Virtue, 58.

15. Jeri Laber, he Courage f Stranges: Coming f Age with the Human Rghs Move ment (New York: Public Mfairs, 2002), 7 4.

16. On the global eplosion of human righs k in the 1970s see he Break through: Human Righs in the 1970s, ed. Jan Eckel and Samuel Moyn (Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014); Moyn, Ast Utopia, chap. 4; James Green, * Cannot Remain Silent: pposition to the Brazilian Militay Dictatoship in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Pess, 2010); Stern ]. Stern, "Witnessing and Aakening Chile: Testimonial Truth and Strugle, 1973-1977 ," and "Digging In:

Counteroficial Chile, 1979-82," in his Battling for Hearts and Minds: Memoy Strugles in Pinochet3 Chile, 197 3-1988 (Durham, NC: Duke University Pess, 2006), 81-136, 196-230; Sarah B. Snyder, Human Rights Activism and the End f the Cold ar: A Trans national Histoy f the Hesinki Network (Cambride: Cambridge University Press, 201 1); Ea Gilligan, Dending Human Rghs in Russia: Segei Kovalyo, Dissident and Human Rights Commssion, 1969-2003 (New York: Routledge, 2004); Benjamin Nathans, "The Dictatorship of Reason: Aleksandr Volpin and the Idea of Rights under 'Developed Socialism,"' Slavic Review 66, no. 4 (Winter 2007): 630-63, and s