Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:05

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Who Leads and Who Lags? A Comparison of

Cheating Attitudes and Behaviors Among

Leadership and Business Students

Aditya Simha , Josh P. Armstrong & Joseph F. Albert

To cite this article: Aditya Simha , Josh P. Armstrong & Joseph F. Albert (2012) Who Leads and Who Lags? A Comparison of Cheating Attitudes and Behaviors Among

Leadership and Business Students, Journal of Education for Business, 87:6, 316-324, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.625998

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.625998

Published online: 30 Aug 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 240

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.625998

Who Leads and Who Lags? A Comparison

of Cheating Attitudes and Behaviors Among

Leadership and Business Students

Aditya Simha, Josh P. Armstrong, and Joseph F. Albert

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington, USAAcademic dishonesty and cheating has become endemic, and has also been studied in great depth by researchers. The authors examine the differences between undergraduate business students (n=136) and leadership students (n=89) in terms of their attitudes toward academic dishonesty as well as their cheating behaviors. They found that business students overall had much more lax attitudes toward cheating than did leadership students, and they also found that business students seemingly appear to cheat more than do leadership students. The authors finally provide some suggestions and implications of their findings.

Keywords: academic dishonesty, business students, cheating behaviors, leadership students

Three things are men most likely to be cheated in, a horse, a wig, and a wife. —Benjamin Franklin (n.d.)

The introductory quotation by Benjamin Franklin may need some updating for the present time and world, and to be suitable in an educational context, the updated quotation may well read, “Three things are students more likely to cheat on, homework, tests, and exams.” This updated quotation will fit right in, as there is a lot of evidence to show that present rates and incidences of cheating and academic dishonesty are extremely high (Firmin, Burger, & Blosser, 2009; Iyer & Eastman, 2006; Simha & Cullen, 2011).

A burgeoning body of evidence suggests that cheating and dishonesty is at an all-time high in academic contexts, and seems to firmly increasing in frequency; academic dishonesty too appears to be increasing all over the world, although in varying ranges (Firmin et al., 2009; Iyer & Eastman 2006; Simha & Cullen, 2011). These ranges have been as low as 13% to as high as 95%, with typical ranges being more or less about 55–60% (Kidwell, Wozniak, & Laurel, 2003; McCabe, Butterfield, & Trevino, 2006; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Nonis & Swift, 1998; Park, 2003).

Correspondence should be addressed to Aditya Simha, Gonzaga Uni-versity, Department of Organizational Leadership, 502 E. Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

Some of the more notorious cheating cases have been covered vividly by news and media outlets—a very recent case involved Japanese students who were accused of having consulted online forums with the help of mobile phones, al-though the competitive university entrance exams were being held (Fackler, 2011). Another notorious case involved Duke University—about 10% of the graduating class in 2008 was caught cheating on a final exam (Conlin, 2007; Simkin & McLeod, 2010). Cheating does not seem to be restricted by national boundaries, either, as Japanese students (Diekhoff, LaBeff, Shinohara, & Yusukawa, 1999), Taiwanese students (Chang, 1995; Lin & Wen, 2007; Shen, 1995), U.S. stu-dents (McCabe, 2009; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; McCabe et al., 2006; Nonis & Swift, 1998), Iranian students (Mir-shekary & Lawrence, 2009; Yahyanejad, 2000), Russian stu-dents (Lupton, Chapman, & Weiss, 2002), Slovakian stustu-dents (Grimes, 2004), and students from Botswana and Swaziland (Gbadamosi, 2004), have all been documented as having en-gaged in cheating behaviors.

Cheating has been particularly associated with business school and business students (Klein, Levenburg, McKendall, & Mothersell, 2007; Levy & Rakovski, 2006; McCabe & Trevino, 1995; Premeaux, 2005), and the general consensus among scholars has been that business students cheat more than other groups of students. McCabe and Trevino found that students intending to enter business fields as well as busi-ness students were more likely than other groups of students to engage in cheating and other forms of academic dishon-esty McCabe et al. (2006) also found that both graduate and

COMPARISON OF CHEATING ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS 317 undergraduate students engaged in academic dishonesty or

cheating behaviors.

Business students have been compared with students from many other disciplines; however, it transpires that no one has ever done a research study comparing business students with leadership students. Leadership as an undergraduate degree is a unique one in that the curriculum consists of a variety of cocurricular leadership opportunities (e.g., retreats, intern-ships, mentoring), besides courses that outline the theoretical facets of leadership in different contexts.

Leadership itself is considered a fairly new academic field, and there has been a lot of debate about it (Barker, 1997); however there is no denying that the field has become im-mensely popular during the last decade or so (Barker, 2001). Therefore, it makes sense to compare business students with leadership students, as students from both categories will very conceivably end up essaying leadership roles in the future.

Comparing business with leadership students is an impor-tant step because the results of this comparison will add to the literature on academic dishonesty and also give some insight on whether tomorrow’s leaders are expected to be ethical. After all, if the students in training to be leaders demonstrate that they cheat often, and have lax attitudes toward cheating and academic dishonesty, then it is only to be expected that as leaders they will prove less than ideal. Several research studies have shown that cheating behaviors in school and college contexts often predict similar dishonest behaviors in the workplace (Lawson, 2004; Nonis & Swift, 1998, 2001; Shipley, 2009; Smyth, Davis, & Kroncke, 2009; Swift & Nonis, 1998), and therefore it begs the question of whether leadership students differ from business students in terms of cheating attitudes and behaviors.

The purpose of this study is to essentially study the following two questions: (a) How do business students’ attitudes toward cheating and academic dishonesty differ from leadership students’ attitudes toward cheating and aca-demic dishonesty? and (b) How do business students’ be-haviors of cheating and academic dishonesty differ from leadership students’ behaviors toward cheating and academic dishonesty?

Answers to the previous questions may help us determine whether leadership students (who are all striving to be to-morrow’s leaders) are leaders or laggards in comparison with business students, in terms attitudes and behaviors related to cheating and academic dishonesty.

In the next portion of this article we provide a brief yet broad overview of the literature on academic dishonesty and cheating. Following the literature review, in the next section we detail the methodology that we rely on to compare busi-ness and leadership students. In the fourth section we present our results, and in the fifth section we present our conclu-sions and discussion, as well as some caveats and directions for further research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

As mentioned previously, academic dishonesty and cheating rates seem to be extremely high in present times and have in fact been described as “rampant” (Simkin & McLeod, 2010, p. 441). To elaborate on that claim, Klein et al. (2007) re-ported that even though the ranges of cheating rates vary from 9% to 95%, the mean is about 70.4%. That fact is alarming; however, one aspect to keep in mind is that definitions of cheating seem to vary from study to study and most studies appear to be cross-sectional and therefore do not do a very good job of tracking cheating behavior longitudinally.

For the most part, student cheating appears to have been given so many different varying definitions, because of the unsuitability of using rational economic modeling to help explain student cheating. Standard economic modeling con-siders that the rational agent weighs the costs and benefits of a criminal action (Becker, 1968; Burrus, McGoldrick, & Schuhmann, 2007). However, this sort of modeling is not suitable to model student cheating behaviors, as there are several differences between student cheating and other crim-inal behaviors. One major difference is that whereas crimcrim-inal behavior typically has outcomes very detrimental to the vic-tims of that crime, the same cannot be said about student cheating victims—similarly, another difference is that pro-fessors can affect the cost of crime in ways that the police cannot (Burrus et al., 2007; Simha & Cullen, 2011). Another aspect of student cheating that is very different from that of criminal behavior is that the person facilitating the cheat-ing gets pleasure by docheat-ing so; such an outcome is unlikely in a nonacademic cheating case (Bunn, Caudill, & Gropper, 1992; Premeaux, 2005; Simha & Cullen, 2011).

All this resultant inconsistency has resulted in a lot of variability in definitions of academic dishonesty and cheat-ing, and also has led to the definition being ambiguous and not clearly understood by students or faculty members (Bar-nett & Dalton, 1981; Burrus et al., 2007; Graham, Monday, O’Brien, & Steffen, 1994; Simha & Cullen, 2011; Wright & Kelly, 1974). These multiple definitions vary from encom-passing a few to multiple forms of academic deviance (Chap-man, Davis, Toy, & Wright, 2004; Hayes & Introna, 2005; Kisamore, Stone, & Jawahar, 2007; Pavela, 1997; Sierra & Hyman, 2008).

However, Cizek (2003) provides a rather holistic defini-tion of cheating,

[Cheating is] any action that violates the established rules governing the administration of a test or the completion of an assignment; any behavior that gives one student an unfair advantage over other students on a test or assignment; or any action that decreases the accuracy of the intended inferences arising from a student’s performance on a test or assignment. (pp. 3–4)

This definition seems to encompass all of the other definitions into it, and so for the purpose of this article is a suitable definition to rely on.

Academic dishonesty is a construct that seems to have a connection and association with three kinds of factors—demographic factors, personality factors, and situa-tional factors. Several demographic factors have been linked with student involvement in academic dishonesty—these factors include gender (Davis, Grover, Becker, & McGre-gor, 1992; Hetherington & Feldman, 1964; Kelly & Wor-rell, 1978; Kisamore et al., 2007; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Nonis & Swift, 2001; Simon et al., 2004; Smyth & Davis, 2004). For the most part, it appears that women are more ethical than men, or at least more willing and likely to report cheating, although McCabe (2001) mentioned that this gen-der difference is less evident in traditionally male-dominated disciplines such as business and accounting.

Age is another demographic variable that seems to have an impact on cheating behaviors in an inversely proportional way, such that younger students seem to be more likely to engage in academic misconduct than older students (Kelly & Worrell, 1978; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Nonis & Swift, 2001; Smyth & Davis, 2004). However, age is not as conclu-sive a variable as is gender (Crown & Spiller, 1998). Other demographic variables of interest are ACT scores (Kelly & Worrell, 1978), and intelligence (Hartshorn & May, 1928; Hetherington & Feldman, 1964; Kisamore et al., 2007).

Some of the personality factors that have an impact or association with cheating are constructs that are measured on the Personality Research Forum (Kelly & Worrell, 1987; Kisamore et al., 2007). Also, cheaters tend to be impulsive, risk taking, attention-seeking, low in responsibility, and tend to be externals on the locus of control measure (Kisamore et al.). Some of the situational factors that appear to have an association with cheating include class size (Nowell & Laufer, 1997), where students appear to cheat more in large classes; seating (Houston, 1986); and academic integrity cul-tures (McCabe, 2005).

METHOD

This study was designed using a student self-report survey questionnaire. Student self-reports are surprisingly accurate for assessing cheating (Cizek, 1999; Finn & Frone, 2004; Lin & Wen, 2007). As a result, we decided to utilize a student self-report as our mode of collecting data. A survey of lead-ership and business students was administered. Our student sample was collected from four different universities for our findings to have a somewhat robust external validity. Students were assured of anonymity and had the option of taking the survey in class or from home through an online version of the same survey. The questions on this survey were obtained and adapted from questions used by earlier studies (Chang, 1995;

De Lambert, Ellen, & Taylor, 2003; Lin & Wen; McCabe, 2009; Pincus & Schmelkin, 2003; Sims, 1993). We used these questions from prior studies in our study to provide our survey with robust validity.

We distributed and sent out 312 surveys or survey links and obtained 225 completed and useable ones, which gave us a response rate of 72.1%. The questionnaire mapped attitudes and frequency of behaviors as they pertained to cheating and academic dishonesty. The survey included two scales—one of which consisted of 18 questions that measured attitudes toward cheating, and the other consisted of 19 questions that measured the frequency of cheating and dishonest behaviors. Both scales were highly reliable (Cronbach’sα=.916 and .963, respectively), and both scales were also valid, as the scale items were chosen and adapted from previous studies (Chang, 1995; De Lambert et al.; Lin & Wen, 2007; McCabe, 2009; Pincus & Schmelkin, 2003; Sims, 1993).

The survey itself took about 15 min for a participant to complete, and essentially captured the following informa-tion: Demographic information about the respondent, an-swers to 18 questions about participants’ attitudes toward cheating and academic dishonesty (attitudes were measured by utilizing the responses of 0 (not cheating), 1 (trivial cheat-ing), or 2 (cheating); and answers to 19 questions about par-ticipants’ behaviors of cheating and academic dishonesty. Frequency of behaviors were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Our completed and usable questionnaires represented a 72.1% response rate, with 89 leadership students and 136 business students completing the questionnaires. The student respondents were split, 44.8% men and 55.2% women; the mean GPA was 3.36 on a 4.00 scale, and the average age was 20.3. We usedt tests to test the two groups of students in terms of their attitudes to cheating and frequency of cheating behaviors. Our results are presented in the following section.

RESULTS

Attitudes Toward Cheating

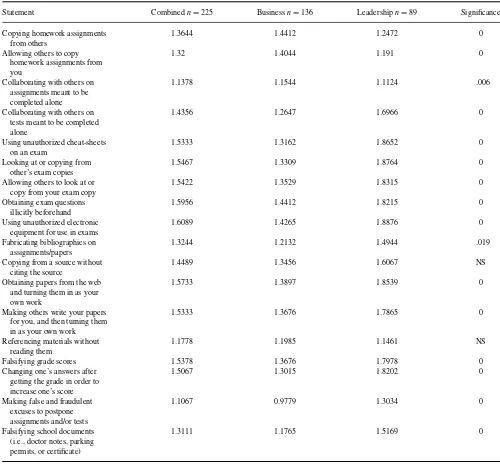

A score of 2 represents serious cheating, a score of 1 repre-sents trivial cheating, and a score of 0 reprerepre-sents not cheat-ing. The two most egregious cheating behaviors, according to students, were using unauthorized electronic equipment for use in exams ( ¯x =1.6089, s=0.585), and obtaining exam questions illicitly beforehand ( ¯x=1.5956, s=0.5755). The two least egregious cheating behaviors, according to stu-dents, were making false and fraudulent excuses to postpone assignments and/or tests ( ¯x = 1.1067, s= 0.67), and ref-erencing materials without reading them ( ¯x =1.1778, s= 0.60).

The responses from business versus leadership students were examined; we found significant differences with respect

COMPARISON OF CHEATING ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS 319 TABLE 1

Student Attitudes to Cheating

Statement Combinedn=225 Businessn=136 Leadershipn=89 Significance Copying homework assignments

from others

1.3644 1.4412 1.2472 0

Allowing others to copy homework assignments from you

1.32 1.4044 1.191 0

Collaborating with others on assignments meant to be completed alone

1.1378 1.1544 1.1124 .006

Collaborating with others on tests meant to be completed alone

1.4356 1.2647 1.6966 0

Using unauthorized cheat-sheets on an exam

1.5333 1.3162 1.8652 0

Looking at or copying from other’s exam copies

1.5467 1.3309 1.8764 0

Allowing others to look at or copy from your exam copy

1.5422 1.3529 1.8315 0

Obtaining exam questions illicitly beforehand

1.5956 1.4412 1.8215 0

Using unauthorized electronic equipment for use in exams

1.6089 1.4265 1.8876 0

Fabricating bibliographies on assignments/papers

1.3244 1.2132 1.4944 .019

Copying from a source without citing the source

1.4489 1.3456 1.6067 NS

Obtaining papers from the web and turning them in as your own work

1.5733 1.3897 1.8539 0

Making others write your papers for you, and then turning them in as your own work

1.5333 1.3676 1.7865 0

Referencing materials without reading them

1.1778 1.1985 1.1461 NS

Falsifying grade scores 1.5378 1.3676 1.7978 0

Changing one’s answers after getting the grade in order to increase one’s score

1.5067 1.3015 1.8202 0

Making false and fraudulent excuses to postpone assignments and/or tests

1.1067 0.9779 1.3034 0

Falsifying school documents (i.e., doctor notes, parking permits, or certificate)

1.3111 1.1765 1.5169 0

to 16 of 18 attitudes. The only two attitudes that did not seem to have any difference between the two groups were those pertaining to copying from a source without citing the source and referencing materials without reading them. For most other attitudes, it appeared that business students had a much more relaxed attitude toward what constitutes cheating than did leadership students. However, for a few attitudes, it transpired that business students had much more serious attitudes than did leadership students (for example, allowing others to copy homework assignments from you, copying homework assignments from others, and collaborating with others on tests meant to be completed alone). But then on the whole, for most of the other attitudes, our findings are

consistent with the findings of both Klein et al. (2007) as well as Roig and Ballew (1994). Table 1 provides the different findings with respect to attitudes toward cheating.

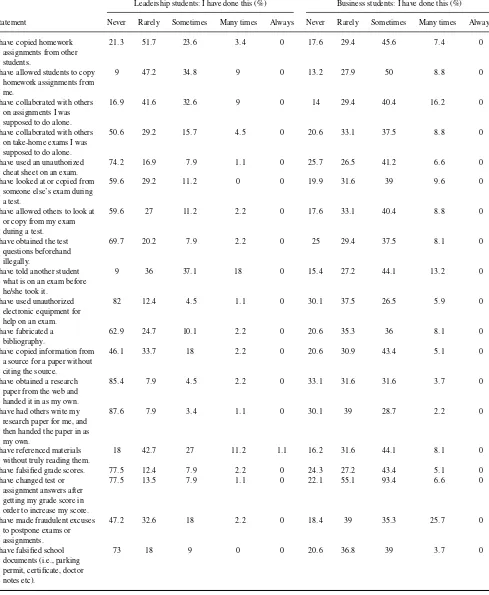

Frequency of Cheating

The scale we used here to capture the frequency of cheating behaviors was through a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Table 2 provides the different frequencies of choices selected by our respondents while answering questions pertaining to cheating behaviors.

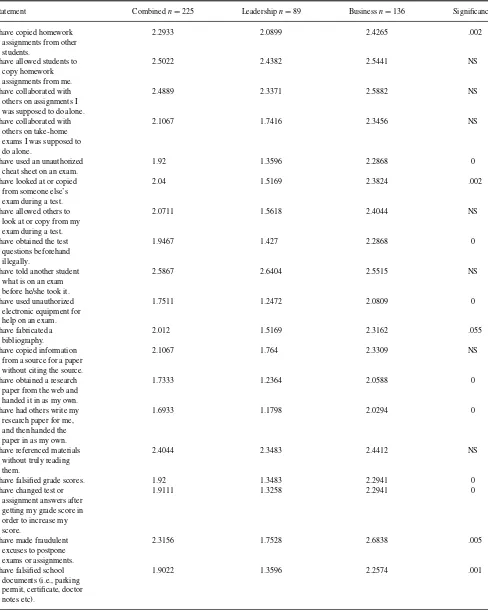

The two cheating behaviors that Table 3 seemed to have been mostly engaged in were telling another student what was

TABLE 2

Student Cheating Behavior Frequencies

Leadership students: I have done this (%) Business students: I have done this (%) Statement Never Rarely Sometimes Many times Always Never Rarely Sometimes Many times Always I have copied homework

assignments from other students.

21.3 51.7 23.6 3.4 0 17.6 29.4 45.6 7.4 0

I have allowed students to copy homework assignments from me.

9 47.2 34.8 9 0 13.2 27.9 50 8.8 0

I have collaborated with others on assignments I was supposed to do alone.

16.9 41.6 32.6 9 0 14 29.4 40.4 16.2 0

I have collaborated with others on take-home exams I was supposed to do alone.

50.6 29.2 15.7 4.5 0 20.6 33.1 37.5 8.8 0

I have used an unauthorized cheat sheet on an exam.

74.2 16.9 7.9 1.1 0 25.7 26.5 41.2 6.6 0

I have looked at or copied from someone else’s exam during a test.

59.6 29.2 11.2 0 0 19.9 31.6 39 9.6 0

I have allowed others to look at or copy from my exam during a test.

59.6 27 11.2 2.2 0 17.6 33.1 40.4 8.8 0

I have obtained the test questions beforehand illegally.

69.7 20.2 7.9 2.2 0 25 29.4 37.5 8.1 0

I have told another student what is on an exam before he/she took it.

9 36 37.1 18 0 15.4 27.2 44.1 13.2 0

I have used unauthorized electronic equipment for help on an exam.

82 12.4 4.5 1.1 0 30.1 37.5 26.5 5.9 0

I have fabricated a bibliography.

62.9 24.7 10.1 2.2 0 20.6 35.3 36 8.1 0

I have copied information from a source for a paper without citing the source.

46.1 33.7 18 2.2 0 20.6 30.9 43.4 5.1 0

I have obtained a research paper from the web and handed it in as my own.

85.4 7.9 4.5 2.2 0 33.1 31.6 31.6 3.7 0

I have had others write my research paper for me, and then handed the paper in as my own.

87.6 7.9 3.4 1.1 0 30.1 39 28.7 2.2 0

I have referenced materials without truly reading them.

18 42.7 27 11.2 1.1 16.2 31.6 44.1 8.1 0

I have falsified grade scores. 77.5 12.4 7.9 2.2 0 24.3 27.2 43.4 5.1 0

I have changed test or assignment answers after getting my grade score in order to increase my score.

77.5 13.5 7.9 1.1 0 22.1 55.1 93.4 6.6 0

I have made fraudulent excuses to postpone exams or assignments.

47.2 32.6 18 2.2 0 18.4 39 35.3 25.7 0

I have falsified school documents (i.e., parking permit, certificate, doctor notes etc).

73 18 9 0 0 20.6 36.8 39 3.7 0

Note.For leadership students,n=89. For business students,n=136.

COMPARISON OF CHEATING ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS 321 TABLE 3

Student Cheating Behaviors

Statement Combinedn=225 Leadershipn=89 Businessn=136 Significance I have copied homework

assignments from other students.

2.2933 2.0899 2.4265 .002

I have allowed students to copy homework assignments from me.

2.5022 2.4382 2.5441 NS

I have collaborated with others on assignments I was supposed to do alone.

2.4889 2.3371 2.5882 NS

I have collaborated with others on take-home exams I was supposed to do alone.

2.1067 1.7416 2.3456 NS

I have used an unauthorized cheat sheet on an exam.

1.92 1.3596 2.2868 0

I have looked at or copied from someone else’s exam during a test.

2.04 1.5169 2.3824 .002

I have allowed others to look at or copy from my exam during a test.

2.0711 1.5618 2.4044 NS

I have obtained the test questions beforehand illegally.

1.9467 1.427 2.2868 0

I have told another student what is on an exam before he/she took it.

2.5867 2.6404 2.5515 NS

I have used unauthorized electronic equipment for help on an exam.

1.7511 1.2472 2.0809 0

I have fabricated a bibliography.

2.012 1.5169 2.3162 .055

I have copied information from a source for a paper without citing the source.

2.1067 1.764 2.3309 NS

I have obtained a research paper from the web and handed it in as my own.

1.7333 1.2364 2.0588 0

I have had others write my research paper for me, and then handed the paper in as my own.

1.6933 1.1798 2.0294 0

I have referenced materials without truly reading them.

2.4044 2.3483 2.4412 NS

I have falsified grade scores. 1.92 1.3483 2.2941 0

I have changed test or assignment answers after getting my grade score in order to increase my score.

1.9111 1.3258 2.2941 0

I have made fraudulent excuses to postpone exams or assignments.

2.3156 1.7528 2.6838 .005

I have falsified school documents (i.e., parking permit, certificate, doctor notes etc).

1.9022 1.3596 2.2574 .001

on an exam before he or she took it ( ¯x =2.5867, s=0.89) and allowing students to copy homework assignments ( ¯x= 2.50, s=0.81). The two cheating behaviors that seemed to have been the ones least engaged in were “having had others write my research paper for me, and then handed the paper in as my own” ( ¯x=1.69, s=0.83), and “obtaining a research paper from the web and handing it over as my own” ( ¯x = 1.73, s=0.89).

The responses from business versus leadership students were examined: we found significant differences with respect to 12 of 19 behaviors. These differences for the most part suggested that business students engaged more frequently in cheating behaviors than did leadership students. provides the different findings with respect to frequencies of cheating behaviors.

DISCUSSION

The essential driver behind this particular study was that we felt that it would be a useful contribution toward the field of academic ethics, and would be useful in examining differences between leadership and business students. Our study’s findings were fairly compatible with other prior stud-ies (Baird, 1980; McCabe & Trevino, 1995) in that business students reported that they engaged in more cheating behav-iors than did leadership students. However, our results also suggest that in some matters, leadership students may have more lax attitudes than business students, and that those at-titudes are more associated with collaborative descriptors. That suggests that a tendency to collaborate with peers is likely to be more pronounced in leadership students. On the whole though, we corroborated Klein et al.’s (2007) findings that business students are on the whole a little more lax in their attitudes toward cheating than are other students (i.e., in this case, leadership students).

However, our study does not aim to suggest that leader-ship students are immune from cheating. All we have demon-strated here is that they appear to cheat less frequently than do business students—although in one case, they appear to cheat more than do business students, but the difference in that case was not a significant one. Scholars have gener-ally agreed that the academic pursuit of leadership is an interdisciplinary process of study (Bennis, 2007); because, a multi-disciplinary approach is best suited for a multi-faceted discipline (Riggio, Ciulla, & Sorenson, 2003). This interdis-ciplinary methodology provides a very holistic outlook on the study of leadership (Newell, 2001). Perhaps, this inter-disciplinary approach, which emphasizes knowledge from fields such as cognitive psychology, social psychology, ed-ucation, sociology, anthropology, biology, history, political science, and a number of other disciplines, contributes to-ward making a more well-rounded student. This may have had some effect on our results, and suggests that perhaps we need to introduce business students to more rounded-out syllabi! Perhaps future researchers could take a look at the

effects of more rounded-out and interdisciplinary syllabi on business students.

Some suggestions that emanate from our findings revolve around the cheating behaviors that tend to be most frequently engaged in. For example, the behavior revolving around telling others what is on an exam before taking the exam can be controlled effectively if there are multiple exam ques-tions that are changed on a frequent basis. Doing so would eliminate the desire of students to inquire about exam ques-tions from other students that have already taken those exams. Similarly, if homework assignments could be individualized to a certain degree, this would possibly eliminate people cheating. When it comes to attitudes about cheating because it appears that making excuses seems less egregious; perhaps instructors and undergraduate curricula could emphasize and continuously reinforce ethics in the classroom. This is very similar to Arlow and Ulrich’s (1985) and Klein et al.’s (2007) conclusions.

Some limitations in our findings would be that there is the distinct possibility that perhaps business students are just more honest with self-reporting cheating behaviors than are leadership students, and so it may not be wholly accurate to state that business students cheat more than leadership students, but then again, research has suggested that most students and respondents are honest while participating in self-reported questionnaires on cheating (Cizek, 1999; Finn & Frone, 2004; Lin & Wen, 2007). Similarly, another lim-itation with this study is that the sample, although robust enough, is not a longitudinal sample, and is instead a cross-sectional sample. Future research efforts could perhaps be conducted in a longitudinal fashion and also include mas-ter’s and doctoral students from business and other disci-plines, as although we do know that undergraduate students cheat, it would be an interesting process to study other cadres as well. On a final note, although our study’s findings sug-gests that business students cheat more than do leadership students—we would like to assert that more research would need to be conducted on a longitudinal basis, to truly dis-cover whether business students cheat more and hold more lax attitudes than other groups of students.

REFERENCES

Arlow, P., & Ulrich, T. (1985). Business ethics and business school grad-uates: A longitudinal study.Akron Business and Economic Review,16, 13–17.

Baird, J. S. Jr. (1980). Current trends in college cheating.Psychology in the Schools,17, 515–522.

Barker, R. A. (1997). How can we train leaders if we do not know what leadership is?Human Relations,50, 343–362.

Barker, R. A. (2001). The nature of leadership. Human Relations, 54, 469–494.

Barnett, D. C., & Dalton, J. C. (1981). Why college students cheat.Journal of College Student Personnel,22, 515–522.

Becker, G. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach.Journal of Political Economy,76, 168–217.

COMPARISON OF CHEATING ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS 323 Bennis, W. (2007). The Challenges of leadership in the modern world:

Introduction to the special issue.American Psychologist,62, 25–33. Bunn, D. N., Caudill, S. B., & Gropper, D. M. (1992). Crime in the

class-room: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. Journal of Economic Education,23, 197–207.

Burrus, R. T., McGoldrick, K., & Schuhmann, P. W. (2007). Self-reports of student cheating: Does a definition of cheating matter? Journal of Economic Education,38, 3–16.

Chang, H. (1995). College student test cheating in Taiwan.Student Coun-seling,41, 114–128.

Chapman, K. J., Davis, R., Toy, D., & Wright, L. (2004). Academic integrity in the business school environment: I’ll get by with a little help from my friends.Journal of Marketing Education,26, 236–249.

Cizek, G. J. (1999).Cheating on tests: How to do it, detect it, and prevent it. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cizek, G. J. (2003).Detecting and preventing classroom cheating: Promot-ing integrity in schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Conlin, M. (2007). Cheating—or postmodern learning.Business Week,4034, 42.

Crown, D. F., & Spiller, M. S. (1998). Learning from the literature on collegiate cheating: A review of empirical research.Journal of Business Ethics,17, 683–700.

Davis, S. F., Grover, C. A., Becker, A. H., & McGregor, L. N. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punish-ments.Teaching of Psychology,33, 39–42.

De Lambert, K., Ellen, N., & Taylor, L. (2003). Cheating—What is it and why do it: A study in New Zealand tertiary institutions of the perceptions and justifications and justifications for academic dishonesty.The Journal of American Academy of Business,3, 98–103.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Shinohara, K., & Yasukawa, H. (1999). College cheating in Japan and the United States.Research in Higher Education,40, 343–353.

Fackler, M. (2011). Internet cheating scandal shakes Japan universi-ties. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/ 2011/03/02/world/asia/02japan.html

Finn, K., & Frone, M. R. (2004). Academic performance and cheating: Moderating role of school identification and self-efficacy.The Journal of Educational Research,97, 115–123.

Firmin, M. W., Burger, A., & Blosser, M. (2009). Affective responses of stu-dents who witness classroom cheating.Educational Research Quarterly, 32, 3–15.

Franklin, B. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.searchquotes.com/quotation/ Three things are men most likely to be cheated in%2C a horse%2C a wig%2C and a wife./7519/

Gbadamosi, G. (2004). Academic ethics: What has morality, culture and administration got to do with its measurement?Management Decision, 42, 1145–1161.

Graham, M., Monday, J., O’Brien, K., & Steffen, S. (1994). Cheating at small colleges: An examination of student and faculty attitudes and behaviors. Journal of College Student Development,35, 255–260.

Grimes, P. W. (2004). Dishonesty in academics and business: A cross-cultural evaluation of student attitudes.Journal of Business Ethics,49, 273–290.

Hartshorne, H., & May, M. A. (1928).Studies in the nature of character. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Hayes, N., & Introna, L. D. (2005). Systems for the production of plagiarists? Journal of Academic Ethics,3, 55–73.

Hetherington, E. M., & Feldman, S. E. (1964). College cheating as a function of subject and situational variables.Journal of Educational Psychology, 55, 212–218.

Houston, J. P. (1986). Classroom answer copying: Roles of acquaintanceship and free vs. assigned seating.Journal of Educational Psychology,78, 230–232.

Iyer, R., & Eastman, J. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty: Are business students different from other college students?Journal of Education for Business,82, 101–110.

Kelly, J. A., & Worrell, L. (1978). Personality characteristics, parent behav-iors, and sex of subject in relation tocheating.Journal of Research in Personality,12, 179–188.

Kidwell, L. A., Wozniak, K., & Laurel, J. P. (2003). Student reports and faculty perceptions of academic dishonesty.Teaching Business Ethics,7, 205–214.

Kisamore, J. L., Stone, T. H., & Jawahar, I. M. (2007). Academic in-tegrity: The relationship between individual and situational factors on misconduct contemplations.Journal of Business Ethics,75, 381–394. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9260-9

Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business school students com-pare?Journal of Business Ethics,72, 197–206. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9165-7

Lawson, R. A. (2004). Is classroom cheating related to business students’ propensity to cheat in the “real world”?Journal of Business Ethics,49, 189–199.

Levy, E., & Rakovski, C. (2006). Academic dishonesty: A zero tolerance professor and student registration choices.Research in Higher Education, 47, 735–754.

Lin, C.-H. S., & Wen, L.-Y. M. (2007). Academic dishonesty in higher education—A nationwide study in Taiwan.Higher Education,54, 85–97. Lupton, R. A., Chapman, K. J., & Weiss, J. (2002). Russian and American college students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies toward cheating. Educational Research,44, 17–27.

McCabe, D. L. (2001). Cheating: Why students do it and how we can help them stop.American Educator,25(4), 38–43.

McCabe, D. L. (2005). It takes a village: Academic dishonesty & educational opportunity.Liberal Education, Summer/Fall, 26–31.

McCabe, D. L. (2009). Academic dishonesty in nursing schools: An empirical investigation. Journal of Nursing Education, 48, 614–623. doi:10.3928/01484834-20090716-07

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty in graduate business programs: Prevalence, causes, and pro-posed action. Academy of Management Learning and Executive, 5, 294–305.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1995). Cheating among business students: A challenge for business leaders and educators.Journal of Management Education,19, 205–218.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influ-ences on academic dishonesty: A multi-campus investigation.Research in Higher Education,38, 379–396.

Mirshekary, S., & Lawrence, A. (2009). Academic and business ethical misconduct and cultural values: A cross-national comparison.Journal of Academic Ethics,7, 141–157.

Newell, W. H. (2001). A theory of interdisciplinary studies.Issues in Inte-grative Studies,19, 1–24.

Nonis, S. A., & Swift, C. O. (1998). Deterring cheating behavior in the marketing classroom: An analysis of the effects of demographics, attitudes and in-class deterrent strategies.Journal of Marketing Education,20, 188–199.

Nonis, S. A., & Swift, C. O. (2001). Personal value profiles and eth-ical business decision. Journal of Education for Business, 76, 251– 256.

Nowell, C., & Laufer, D. (1997). Undergraduate student cheating in the fields of business and economics.Journal of Economic Education,28, 3–12.

Park, C. (2003). In other (people’s) words: Plagiarism by university students—Literature and lessons.Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education,28, 471–488. doi:10.1080/0260293032000120352

Pavela, G. (1997). Applying the power of association on campus: A model code of academic integrity. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 97–118.

Pincus, H. S., & Schmelkin, L. P. (2003). Faculty perceptions of academic dishonesty: A multidimensional scaling analysis.Journal of Higher Ed-ucation,74, 196–209.

Premeaux, S. R. (2005). Undergraduate student perceptions regarding cheating.Journal of Business Ethics,62, 407–418. doi:10.1007/s10551-005–2585-y

Riggio, R. E., Ciulla, J., & Sorenson, G. (2003). Leadership education at the undergraduate level: A liberal arts approach to leadership development. In S. E. Murphy & R. E. Riggio (Eds.),The future of leadership development (pp. 223–236). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Roig, M., & Ballew, C. (1994). Attitudes towards cheating in self and others by college students and professors. The Psychological Record,44(1), 3–12.

Shen, L. (1995). Assessing students’ academic dishonesty in junior colleges in south Taiwan.Chia-Nan Annual Bulletin,21, 97–112.

Shipley, L. J. (2009). Academic and professional dishonesty: Student views of cheating in the classroom and on the job.Journalism & Mass Commu-nication Educator,64, 39–53.

Sierra, J. J., & Hyman, M. R. (2008). Ethical antecedents ofcheating in-tentions: Evidence of mediation. Journal of Academic Ethics,6, 51– 66.

Simha, A., & Cullen, J. B. (2011). Cheating and academic dishonesty: Proac-tive and retroacProac-tive solutions. In C. Wankle & A. Stachowicz-Stanusch (Eds.),Handbook of research on teaching ethics in business and manage-ment education(pp. 473–492). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Simkin, M. G., & McLeod, A. (2010). Why do college students cheat? Journal of Business Ethics,94, 441–453.

Simon, C. A., Carr, J. R., McCullough, S. M., Morgan, S. J., Oleson, T., & Ressel, M. (2004). Gender, student perceptions, institutional commit-ments and academic dishonesty: Who reports in academic dishonesty cases?Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education,29(1), 75–90. Sims, R. L. (1993). The relationship between academic dishonesty and

unethical business practices. Journal of Education for Business, 69, 207–211.

Smyth, M. L., & Davis, J. R. (2004). Perceptions of dishonesty among two-year college students: Academic versus business situations.Journal of Business Ethics,51, 63–73.

Smyth, L. S., Davis, J. R., & Knoncke, C. O. (2009). Students’ perceptions of business ethics: Using cheating as a surrogate for business situations. Journal of Education for Business,84, 229–239.

Swift, C. O., & Nonis, S. A. (1998). When no one is watching: Cheating behavior on projects and assignments.Marketing Education Review,8(1), 27–38.

Wright, J., & Kelly, R. (1974).Cheating: student/faculty views and respon-sibilities.Improving College and University Teaching,22, 31–34 Yahyanejad, M. (2000).Applying Iranian way. Retrieved from http://scf.

usc.edu/∼igsa/pdf files/iranian.pdf