Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:39

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Mind the Gap: Accounting Information Systems

Curricula Development in Compliance With IFAC

Standards in a Developing Country

Mahmoud Mohmad Ahmad Aleqab, Mohammad Nurunnabi & Dalia Adel

To cite this article: Mahmoud Mohmad Ahmad Aleqab, Mohammad Nurunnabi & Dalia Adel (2015) Mind the Gap: Accounting Information Systems Curricula Development in Compliance With IFAC Standards in a Developing Country, Journal of Education for Business, 90:7, 349-358, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1068155

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1068155

Published online: 07 Aug 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 66

View related articles

Mind the Gap: Accounting Information Systems

Curricula Development in Compliance With IFAC

Standards in a Developing Country

Mahmoud Mohmad Ahmad Aleqab and Mohammad Nurunnabi

Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Dalia Adel

Dar Alhekma University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

The authors examine the consistency between the current practices in designing and teaching accounting information systems (AIS) curricula and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) requirements for International Education Practice Statement 2 and International Education Standards 2. Utilizing a survey and interviews data in Jordan, the results show several issues that contribute to the inconsistency of IFAC’s requirements, including a lack of Arabic textbooks, qualified staff, training, computer laboratories, and faculty support and finance. This is the first study to provide a model curriculum and course learning outcomes of an AIS course. There is urgent attention required from local and international policymakers.

Keywords: accounting information systems, curricula, IAESB, IEPS, IES, IFAC, Jordan

INTRODUCTION

Given the current focus on strengthening the accounting profession following the recent financial scandals, particu-larly in the United States (including Enron and WorldCom) and the recent global financial crisis, the importance of developing and enhancing university accounting education is widely recognized (Evans, Burritt, & Guthrie, 2010; International Federation of Accountants [IFAC], 1995, 2012; Jackling & de Lange, 2009). However, accounting education has failed to keep up with the changes in account-ing practices caused by technology and accountaccount-ing students are not well prepared for the workplace (Er & Ng, 1989; Gallhofer, Haslam, & Kamla, 2009).

Prior research on the impact of information systems (IS) or information technology (IT) has proliferated. The uses of IS in a globalized world have multiplied. However, there is limited research focused on the curricula issues of account-ing, in particular accounting information systems (AIS;

Andrews & Wynekoop, 2004; Carnegie & Napier, 2010; Chayeb & Best, 2005; Daigle, Hayes, & Hughes, 2007; Davis & Leitch, 1988; Groomer & Murthy, 1996; Krippel & Moody, 2007; Strong, Portz, & Busta, 2006; Wessels, 2005). Most of these studies are based on developed countries. It is argued that aligning AIS curricula with IFAC would be help-ful for competent professional accountants and also improve the employability of accounting graduates (Ahmad & Gao, 2004; Hastings & Solomon, 2005; Wessels, 2005). Hence, the present study contributes to the literature of a developing country’s experience with reference to Jordan, which has made substantial progress in its higher education sectors in recent years. As of 2015, there were 10 public universities, 19 private universities, and 50 community colleges in Jordan. University education in Jordan commenced with the estab-lishment of the University of Jordan in 1962. In 1989, the Al-Ahliyya Amman University was established as the first pri-vate university. According to the Ministry of Higher Educa-tion and Scientific Research of Jordan, there were approximately 236,000 students enrolled to study in private and public universities, 28,000 of them are Arab or foreign nationalities. The ministry described the importance of higher education in Jordan and noted that, to maintain and develop the quality of higher education, the next phase required a Correspondence should be addressed to Mohammad Nurunnabi, Prince

Sultan University, College of Business Administration, Department of Accounting, Prince Nasser Bin Farhan Street and Rafha Street, P.O. Box 66833, Riyadh 11586, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: mnurunnabi@psu.edu.sa JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 90: 349–358, 2015 CopyrightÓTaylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1068155

reconsideration of the law that governs public and private universities, as well as higher education, for example: the Law of Higher Education No. 23 (2009), and the Jordanian Universities Law No. 20 (2009) (http://www.mohe.gov.jo/). The World Bank Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes (World Bank, 2004) regarding accounting and auditing raised considerable concerns about accounting edu-cation and its curricula in Jordan. Therefore, this study con-siders the following research questions:

To what extent are the AIS’s curricula consistent with

the requirements and standards of the IFAC?

What factors are hindering noncompliance with IFAC

requirements?

What should be the model curriculum for an AIS

course that is in compliance with IFAC?

This article is organized into six sections. The next sec-tion presents the prior literature; the following secsec-tion explains learning theory; the next section after that provides the research methodology; the subsequent discusses the findings; and finally, the last section contains the conclu-sions, policy implications, and limitations of this study.

PRIOR LITERATURE

IT is becoming critical for accountants due to the growing awareness of IT among business personnel and the increasing number of computerized accounting systems that are being implemented in organizations (Krippel & Moody, 2007).

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) recommended that computer and IT concepts should be part of the knowledge, skills, and abilities of accounting professionals (AICPA, 2008). Regarding the importance of IFAC’s initiative toward global accounting standards, McPeak, Pincus, and Sundem (2012) noted that International Education Standards (IES), which are devel-oped by the International Accounting Education Standards Board (IAESB), influence accounting education and train-ing worldwide. Even though they are less than a decade old, the IES are enforced through the member bodies of the IFAC and professional accountancy organizations through-out the world. The goal of the IES is to ensure that eco-nomic decision makers can rely on the competence of professional accountants regardless of the country where the accountants received their education and training.

However, differing cultures, languages, and social, educa-tional, and legal systems pose a challenge for the development of a globally applicable set of international accounting educa-tion standards. The IFAC issued their first guideline on IT in the accounting curriculum in 1995. These guidelines were then reviewed and IFAC issued a further set of guidelines: IES 2— Content of Professional Accounting Education Programs; IES 6—Assessment of Professional Capabilities and Competence;

and The International Education Practice Statement (IEPS) 2—IT for Professional Accountants (IFAC, 2010).

The IFAC have provided guidance regarding topics of importance for preparing professional accountants who work with IT (Al-Akra, Ali, & Marashdeh, 2009; AICPA, 2008; Saville, 2007). Accordingly, the IEPS 2 provides guidelines to help the member bodies to prepare profes-sional accountants to effectively work in an IT environ-ment. These guidelines are summarized into three basic areas of knowledge for accountants: general IT, IT control knowledge, and competency requirements. Furthermore, knowledge and competencies are presented that are relevant to accountants in their roles as users, managers, designers, and evaluators (auditors) of IT systems. IFAC (2012) rec-ommended that undergraduate students should achieve broad knowledge in IT. This knowledge of IT could be cov-ered by various AIS topics and complemented within the auditing/accounting subjects (de Lange & Watty, 2011).

Regarding AIS curriculum design, Gromer and Murthy (1996) showed that there is a lack of homogeneity and har-mony in this course curriculum via the feedback received from the surveyed institutions. They have concluded that inefficient guidance and supervision related to the AIS module and the background of the instructors in accounting are important factors when developing AIS curricula. Investigating the curriculum in Australian Universities, Chayeb and Best (2005) found evidence for the lack of a standardized curriculum of AIS. Prior research has also emphasized that good curricula design helps to gain AIS skills for accounting graduates. Romney & Steinbart (2014) highlighted the importance of IT skills for accounting grad-uates from different levels, as follows: auditors need to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of information pro-duced by the AIS; and tax accountants must understand the client’s AIS adequately for tax planning and compliance work. IFAC (2012) therefore noted that these topics include the transaction cycle approach and the business process approach to all organizational information. Hunton (2002) debated against the ambiguity faced by AIS researchers regarding the direction of AIS, thus requiring a more signif-icant contribution to AIS theory and knowledge. Wessels (2005) also looked at the requirements of various profes-sional bodies to determine a consensus of technology skills requirements. He concluded that, even with extensive guidelines from international and national professional bod-ies, sometimes the direction of AIS curriculum content may come from entities closer to home. It has also been found that a shortage of well-prepared AIS academics in account-ing impede curriculum design (McPeak et al., 2012).

LEARNING THEORY

According to learning theory, technology has affected accounting education (Bromson, Kaidonis, & Poh, 1994).

Flanagan and Stewart (1991) earlier argued that “teaching and learning ’are inextricably connected, but

. . . [w]hen a teaching approach is being developed

con-sideration should be given to how students learn and the contribution that computerized accounting can make to enhance the learning of accounting concepts” (p. 284). They suggested that a teaching approach should offer the opportunity to experience, observe, and reflect concepts and testing implications. In this context, Preston (1992) advised that further research is required to better under-stand the pedagogic implications of technology in accounting education. Preston also pointed out that “curriculum developments would take place as a result of negotiation undertaken in the interaction between school, local community, teacher, student and the wider society, rather than resulting from decrees from bureaucrats or education ministers” (p. 51). In accounting education, AIS deals with computer-based IS for processing accounting data. The learning and teaching approach should be integrated to convey accounting and IT con-cepts. Therefore, Bromson et al. (1994) asserted that “the curriculum in undergraduate accounting courses has been influenced by a number of external factors, including professional associations; accreditation authorities; employers of graduates; and expectations of prospective students” (p. 112). This demonstrates that accounting fac-ulty should design AIS curricula which accommodate the current best practices of IS. The application of this theory can be done through discursive as well as empirical methods (Kolb, 1984).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study adopts a mixed methodology that uses both a survey and semistructured interviews. A mixed methodol-ogy provides richer and more in-depth findings than a sin-gle method (Creswell, 2007).

Firstly, following ethical approval, we conducted an online survey of all 29 Jordanian universities who offer the AIS course in 2013 (see the Appendix). The question-naire was designed based on IFAC requirements for IT knowledge issued in 2010. The respondents were selected randomly from the universities’ websites and email invi-tations were sent to complete the questionnaire. Demo-graphics, experience, and research interests were tested to see how qualified the instructors are, and authoritative guidance was referenced. Initially, the questionnaire was sent to 120 instructors (total population). A total of 90 respondents replied. But, 40 of 90 did not fill in the ques-tionnaire effectively. After the follow-up, the usable response was 54. Hence, a true response was 60% (54 of 90). This level of response is typically seen as being acceptable when employing a survey method (Krippel & Moody, 2007). To test the response bias in our data, a

chi-square test on the responses of early and late response was conducted. The result does not show a sta-tistical significant difference (at the .05 level). Therefore, the nonresponse rate is unlikely to be a problem for this study.

The survey questionnaire was split into three parts: demographic questions, contents and assessment, and fac-tors that are related to IFAC noncompliance. The selection of questionnaire content was further informed by prior research (Andrews & Wynekoop, 2004; Chayeb & Best, 2005; Daigle et al., 2007; Groomer & Murthy, 1996; Krip-pel & Moody, 2007). In addition, selected items were broadly based on IFAC standards set for teaching, content, and assessment issues in AIS: IEPS 2, IES 2, IES 6, IFAC Education Committee’s (IFAC, 2003) International Educa-tion Guideline 11, and IFAC’s (2012) IAESB Terms of Reference.

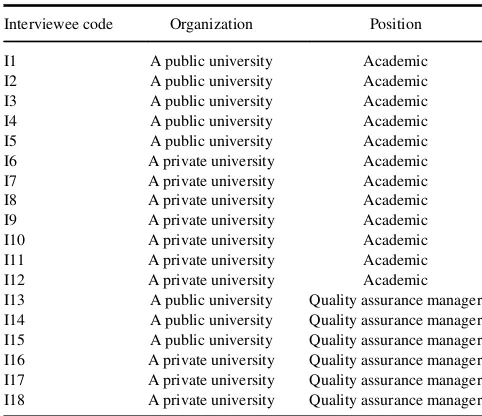

In the next part of the mixed methodology, we con-ducted 18 semistructured interviews (see Table 1). The interviewees was selected from public and private universi-ties: five public university academics, and seven private university academics, three public university quality ance managers and three private university quality assur-ance managers. All of the interviewees were anonymized and their confidentiality was guaranteed. Following Cres-well (2007), the reliability and validity of the interviews were maintained. For instance, data were translated from Arabic to English and checked twice, the same questions were asked of all interviewees, interview coding was main-tained so that the same theme could be documented effec-tively, and interviewees were selected based on the research objectives of the study.

TABLE 1

Interviewees of the Study (nD18)

Interviewee code Organization Position

I1 A public university Academic I2 A public university Academic I3 A public university Academic I4 A public university Academic I5 A public university Academic I6 A private university Academic I7 A private university Academic I8 A private university Academic I9 A private university Academic I10 A private university Academic I11 A private university Academic I12 A private university Academic I13 A public university Quality assurance manager I14 A public university Quality assurance manager I15 A public university Quality assurance manager I16 A private university Quality assurance manager I17 A private university Quality assurance manager I18 A private university Quality assurance manager

Note:IDInterviewee.

AIS CURRICULA DEVELOPMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH IFAC STANDARDS 351

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

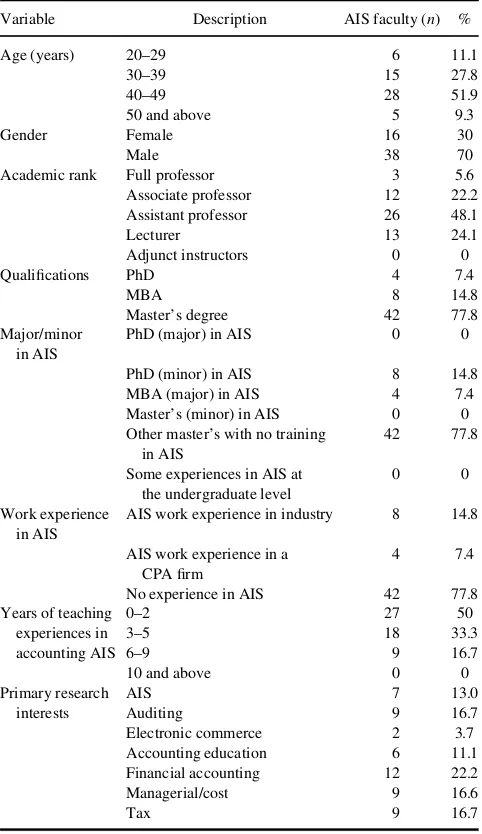

Demographic Information and AIS Instructors

In terms of the demographic information of the respondents, it is observed from Table 2 that the majority of the respond-ents were between 40 and 49 years old. Predominantly, male respondents participated in this research (70%). Regarding academic rank, the most of the respondents were assistant professors (48.1%). The majority of the respond-ents had a master’s qualification (77.8%). Only 7.4% were PhD holders (see Table 2). This finding is dissimilar with that of Groomer and Murthy (1996), who reported that 73% of their respondents had a PhD qualification.

Prior research also suggests that respondents with a major/minor in AIS and work experience are essential to

the development of accounting curricula (Davis & Leitch, 1988). Table 2 shows there were no PhD holders who maj-ored in IS. Interestingly, the majority of instructors (77.8%) held a master’s qualification other than IS. These instructors also had no training in IS. There is a relationship between education and work experience in IS. For instance, the respondents who held a master’s in another discipline also had no work experience. Hence, only 22.2% respondents had IS related work experience in the IS industry and the CPA firms. This indicates that an increasing number of instructors are involved in AIS curricula development with-out having sufficient IT knowledge. The findings are incon-sistent with those of Davis and Leitch (1988) and Groomer and Murthy (1996) who suggested that work experience is an important element for curricula design. Regarding teach-ing experience, 50% of the respondents had between zero and two years of teaching experience, while the others had three years and above. It is further observed that only 13% of instructors were interested in AIS related research in Jor-danian universities. Chayeb and Best (2005) found that 44.44% Australian instructors were actively involved in AIS related research.

Current Contents of the AIS Curricula and Assessment

In relation to contents and syllabus, the majority of the instructors cover theoretical content rather than technical content (e.g., 68.5% transaction cycles, 53.7% accounting software, 42.6% database management, 37% enterprise resource planning, and 37% auditing of IS; see Table 3). None of the instructors used business process reengineering (BPR), executive information systems (EIS), IT architec-ture, decision support systems (DSS), expert systems (ES), or electronic data interchange (EDI). This is surprising because according to IFAC requirements, BPR, EIS, DSS,

TABLE 2

Characteristics of the AIS Faculty/Instructors, Respondents (nD54)

Variable Description AIS faculty (n) %

Age (years) 20–29 6 11.1

30–39 15 27.8

40–49 28 51.9

50 and above 5 9.3

Gender Female 16 30

Male 38 70

Academic rank Full professor 3 5.6 Associate professor 12 22.2 Assistant professor 26 48.1

Lecturer 13 24.1

Adjunct instructors 0 0

Qualifications PhD 4 7.4

MBA 8 14.8

Master’s degree 42 77.8 Major/minor

in AIS

PhD (major) in AIS 0 0

PhD (minor) in AIS 8 14.8 MBA (major) in AIS 4 7.4 Master’s (minor) in AIS 0 0 Other master’s with no training

in AIS

42 77.8

Some experiences in AIS at the undergraduate level

0 0

Work experience in AIS

AIS work experience in industry 8 14.8

AIS work experience in a CPA firm

4 7.4

No experience in AIS 42 77.8 Years of teaching 0–2 27 50

experiences in 3–5 18 33.3 accounting AIS 6–9 9 16.7

10 and above 0 0

Primary research AIS 7 13.0 interests Auditing 9 16.7 Electronic commerce 2 3.7 Accounting education 6 11.1 Financial accounting 12 22.2 Managerial/cost 9 16.6

Tax 9 16.7

TABLE 3

Contents of AIS Course According to IFAC Requirements

Content/topics covered in the AIS course AIS faculty (n) %

Accounting software 29 53.7

auditing of IS 20 37.0

Business process reengineering (BPR) 0 0 Database management systems (DBMS) 23 42.6 Decision support systems (DSS) 0 0 Electronic commerce 12 22.2 Electronic data interchange (EDI) 0 0 Enterprise resource planning (ERP) 20 37.0 Executive information systems (EIS) 0 0

Expert systems (ES) 0 0

Internal control 11 20.4

IT architecture 0 0

Management information systems (MIS) 12 22.2 Supply chain management 12 22.2 Systems design and the systems development life cycle 11 20.4 Transaction processing (cycles) 37 68.5

ES, EDI must be incorporated in the AIS curricula (Andrews & Wynekoop, 2004).

Table 4 presents the instructors in Jordan who follow traditional assessment criteria including case studies, mid-semester exam and final exam. As noted, technical content is significantly missing from the content of AIS courses in Jordanian universities; therefore, assessment does not fol-low a particularly technical path. For example, no spread-sheet assignment or group project is assessed. This happens because the majority of the instructors have had no formal AIS training. Chayeb and Best (2005) found that AIS instructors in Australia use more Spreadsheet assignments. To deepen this argument, the Jordanian instructors were asked to name the software that they were use when teach-ing the AIS curricula. In relation to software usage on the AIS curricula, 92.5% instructors use Microsoft (MS) Access (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA; see Table 5). None of the instructors use MS Project (Microsoft Corpora-tion, Seattle, WA), JIWA Financials (JIWA Financials, North Sydney, Australia), MYOB, or Quicken (Intuit, Inc., Mountain View, CA). Very few instructors used SAP R/3 (SAP SE, Walldorf, Germany) or Solution 6 (MYOB Tech-nology Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia). It is found that these instructors held a PhD (minor) or MBA (major) in AIS. In the Jordanian setting it is also found that as the software becomes more sophisticated it will be less likely to be used, particularly with regard to the level of application of the software. According to IFAC’s IES 2, “whichever form(s) of assessment are used to assess candidates’ IT knowledge, IFAC member bodies should consider whether the assess-ment(s) include sufficient coverage of IT knowledge and practical application” (IFAC, 2010, p. 136).

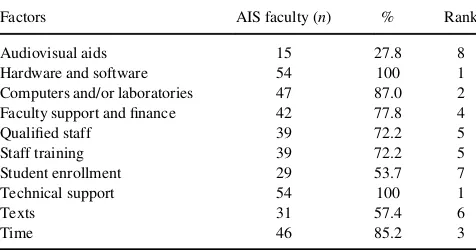

Factors Affecting the Delivery of the AIS Module and Noncompliance With IFAC

Prior research suggests that there are various issues that affect the delivery of an AIS module (Daigle et al., 2007; Wessels, 2005). In this study, all of the respondents agreed that there

was a lack of hardware and software facilities: 87% of the instructors raised significant concerns regarding computers or laboratories, while 72% believed that a lack of qualified staff and training facilities is impeding the delivery of their AIS course (see Table 6). As mentioned, most of the instructors did not have an IT background and at the same time the univer-sities are reluctant to provide financing so that they can gain an IT certificate or professional training. Some of the respondents also complained about an excessive teaching overload, which is not helpful to the development of an AIS curriculum. A total of 83.3% respondents were unfamiliar with the IFAC requirements.

Moreover, 57.4% instructors were critical about the lack of availability of textbooks. Interestingly, the majority of the instructors (92.5%) were using Marshall B. Romney & Paul J. Steinbart’s Accounting Information Systems (Rom-ney & Steinbart, 2014). The respondents clarified the view that language barriers may be the reason why English texts are chosen in Jordan. Although most of the instructors delivered the AIS module in Arabic, the only available texts are in the English language.

Findings From the Interviews Regarding Current Problems and Solutions to Minimize the Gap

The interviewees were asked about the major problems of developing an AIS curriculum that is in compliance with

TABLE 4 Assessment Applied in AIS

Assessment AIS faculty (n) %

Accounting software assignment 21 38.9

Case studies 46 85.2

Class presentations 20 37.0 Database assignment 21 38.9 Enterprise resource planning software assignment 19 35.2

Final exam 54 100

Hand-in exercises 12 22.2

Midsemester exam 54 100

Spreadsheet assignment 0 0 Theoretical assignment 0 0 Tutorial participation 0 0

TABLE 5 Software Usage in AIS

Software AIS faculty (n) %

Attache 11 20.4

JIWA Financials 0 0

MS Access 50 92.5

MS Excel 11 20.4

MS Project 0 0

MYOB 0 0

Quicken 0 0

SAP R/3 2 3.7

Solution 6 3 5.6

TABLE 6

Factors Affecting Delivery of the AIS Module

Factors AIS faculty (n) % Rank

Audiovisual aids 15 27.8 8 Hardware and software 54 100 1 Computers and/or laboratories 47 87.0 2 Faculty support and finance 42 77.8 4 Qualified staff 39 72.2 5

Staff training 39 72.2 5

Student enrollment 29 53.7 7 Technical support 54 100 1

Texts 31 57.4 6

Time 46 85.2 3

AIS CURRICULA DEVELOPMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH IFAC STANDARDS 353

IFAC. The majority of the interviewees agreed that there is a major loophole in the current structure of the AIS cur-riculum and the following themes were identified: First, translation is a huge concern that creates a gap in AIS cur-riculum development. The majority of the interviewees agreed that most of the university academics taught their program in Arabic, but there were no Arabic texts avail-able. Instead, the instructors had to rely on English-lan-guage textbooks. One interviewee from a public university said that:

Our students are taught an accounting program in Arabic. To give them an English textbook all of a sudden creates big problems for them.

One of the quality assurance managers from a private university opined that:

Yes, we are aware of that fact. My university is closely working in the development of an Arabic textbook.

Second, there is a lack of qualified instructors of AIS. All of the interviewees suggested that without qualified instructors the systematic curriculum development of AIS is quite impossible. The following four comments repre-sented this issue:

Some universities choose accounting instructors who have no background in AIS. As you know, it is difficult to teach

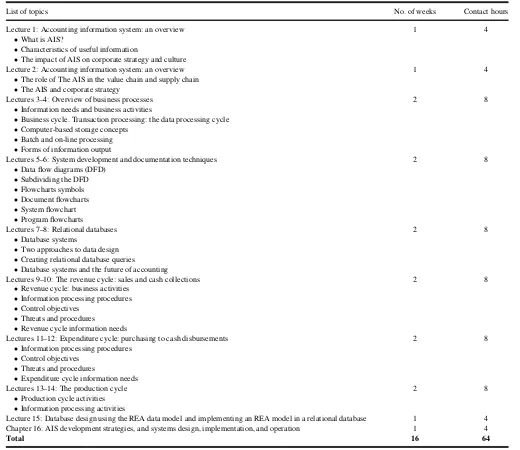

TABLE 7

Model Curriculum of AIS Course Complying With IFAC

List of topics No. of weeks Contact hours

Lecture 1: Accounting information system: an overview 1 4

What is AIS?

Characteristics of useful information

The impact of AIS on corporate strategy and culture

Lecture 2: Accounting information system: an overview 1 4

The role of The AIS in the value chain and supply chain The AIS and corporate strategy

Lectures 3–4: Overview of business processes 2 8

Information needs and business activities

Business cycle. Transaction processing: the data processing cycle Computer-based storage concepts

Batch and on-line processing Forms of information output

Lectures 5–6: System development and documentation techniques 2 8

Data flow diagrams (DFD) Subdividing the DFD Flowcharts symbols Document flowcharts System flowchart Program flowcharts

Lectures 7–8: Relational databases 2 8

Database systems

Two approaches to data design Creating relational database queries

Database systems and the future of accounting

Lectures 9–10: The revenue cycle: sales and cash collections 2 8

Revenue cycle: business activities Information processing procedures Control objectives

Threats and procedures Revenue cycle information needs

Lectures 11–12: Expenditure cycle: purchasing to cash disbursements 2 8

Information processing procedures Control objectives

Threats and procedures

Expenditure cycle information needs

Lectures 13–14: The production cycle 2 8

Production cycle activities Information processing activities

Lecture 15: Database design using the REA data model and implementing an REA model in a relational database 1 4 Chapter 16: AIS development strategies, and systems design, implementation, and operation 1 4

Total 16 64

a course without specialized instructors. (Public university academic)

There is a difference between accounting instructors and accounting instructors with experience in AIS. The manage-ment must address this issue. (Private university academic)

There are low numbers of PhDs on AIS in Jordan. The gov-ernment may encourage AIS PhDs by providing more scholarships. (Quality assurance manager from a private university)

We provide some training for the introductory level of IS. I know that this is not sufficient. The government and the uni-versity management should put more AIS training for cur-rent instructors. (Quality assurance manager from a public university)

Thirdly, 9 of 12 university academics (five from public and four from private university) raised issues about the computer laboratory. It is found that public universities pro-vide less computer laboratory hours than private universi-ties. The interviewees also suggested that students should have previous knowledge of IS. The interviewees agreed that there should be a prerequisite of AIS course. One pri-vate university academic opined that:

Computer laboratory hours are very important for the AIS course. The students should be familiar with various soft-ware programs and we should provide sufficient laboratory hours. However, prior knowledge of IS is very important.

Finally, the interviewees, in particular university aca-demics (12 of 18), raised concerns about what contents should be included. One interviewee from a public univer-sity made recommendations about the principal objective of AIS course:

This course should be designed to enable students to have exposure and experience on the system concepts, data proc-essing technology, system documentation techniques, infra-structure for e-business, security and control measures in computer-based IS and AIS applications in business.

A total of 12 academics viewed that there are nine broader areas for the AIS curriculum, as follows: (a) accounting information system: an overview, (b) overview of business processes, (c) system development and documen-tation techniques, (d) relational databases, (e) the revenue cycle: sales and cash collections, (f) expenditure cycle: pur-chasing to cash disbursements, (g) the production cycle, (h) database design using the REA data model and implement-ing an REA model in a relational database, and (i) AIS development strategies, and systems design, implementation, and operation. However, there were some disagreements about the time distribution of these contents. For example,

10 of 12 academics suggested that this course should be based on 90 hr (48 hr lectures, 16 hr tutorial, and 26 hr computer laboratory). This course is typically 16 weeks long. However, the other two academics suggested 79 hr (44 hr lectures, 20 hr tutorial, and 15 hr computer labora-tory). The majority of the interviewees (10 of 12 academics) also suggested that instructors may add one or two revision weeks in a 16 weeks long AIS course (i.e., in a semester). Six quality assurance managers did not make any comment regarding the contents of the AIS curriculum because their role is to provide quality assurance of the overall university education rather than focus on a particular course.

Six quality assurance managers from both private and public universities reported on the necessity of having defined course learning outcomes. One private university quality assurance manager opined that:

Defined course learning outcomes of a course are indeed the key to maintain continuous quality assurance process.

Based on the findings of study and in compliance with IFAC a model curriculum of an AIS course is presented in Table 7.

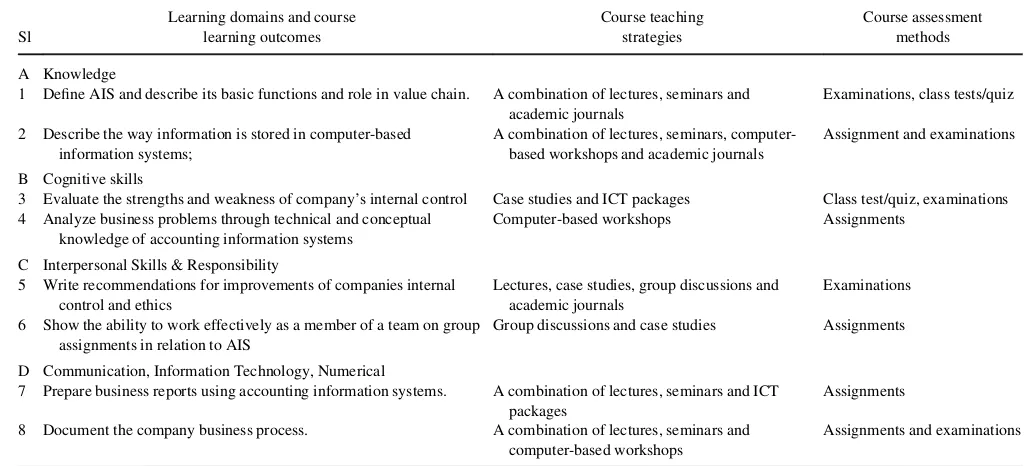

Both quality assurance managers and academics (16 of 18) agreed that the outcomes for four learning domains could be met for an AIS course, namely: (a) knowledge, (b) cognitive skills, (c) interpersonal skills and responsibility, and (d) communication, IT (see Table 8). Two interviewees disagreed about having four learning domains. Table 8 shows that there are eight course learning outcomes of an AIS course. Each learning domain has two course learning outcomes. One public university academic opined that:

The course learning outcomes are very important for an AIS course. It tells the instructors exactly what the course intends to offer and shows if it meets the assessment criteria.

CONCLUSION, POLICY IMPLICATIONS, AND LIMITATIONS

Most of the prior studies have focused on AIS curricu-lum in developed countries (Chayeb & Best, 2005; Daigle et al., 2007; Groomer & Murthy, 1996; Krippel & Moody, 2007). Prior research also demonstrates that there is a gap in AIS curriculum development in com-plying with IFAC requirements (Chayeb & Best, 2005; Krippel & Moody, 2007). Meanwhile, some recent regu-lations in Jordan (i.e., the Company Law 1997, the tem-porary Securities Law 1997, and the Securities Law 2002) have been initiated to foster the accounting pro-fessions (IFRS Foundation, 2014). For instance Article No. 183 of the company’s law requires that, “A Public Shareholding Company shall organize its accounts and AIS CURRICULA DEVELOPMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH IFAC STANDARDS 355

keep its registers and books in accordance with the rec-ognized international accounting and auditing stand-ards.” Accordingly, this study investigates the current practices in designing and teaching AIS curriculum and IFAC’s requirements for international education stand-ards (i.e., IEPS 2 and IES 2). Based on a mixed method-ology (i.e., a survey of all public and private universities in Jordan, and 18 interviewees from AIS academics and quality assurance mangers) and learning theory, this study makes several contributions to accounting educa-tion research, particularly curricula development of AIS. First, this study provides a model curriculum and course learning outcomes for an AIS course complying with IFAC requirements. This is the first study to date to provide a model curriculum of AIS. This will be helpful to academics, local policymakers, and the international policymakers (i.e., IFAC) who wish to minimize the existing gap of AIS curric-ulum development in a developing country such as Jordan. It is worth noting that Chayeb & Best (2005) evidenced a lack of a standardized curriculum of AIS in Australia but did not provide a model curriculum. Secondly, although Jordan has made substantial progress in accounting regulation and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) compli-ance in recent years, a lack of standardized AIS curriculum is of concern. The inconsistency between the AIS curriculum in Jordan and IFAC standards underlines the need for policy-makers to understand the present accounting curricula practices in private and public universities. The findings from surveys and interviews identify several issues that con-tribute to inconsistency with IFAC’s, including a lack of Arabic textbooks, AIS qualified staff, training, computer

laboratories, and faculty support and finance. Unlike Aus-tralia (Chayeb & Best, 2005), the instructors in Jordan were not actively involved in AIS-related research and did not use a spreadsheet as an assignment tool. The findings of this study confirm the findings of the World Bank (2004), which earlier reported on the poor quality of accounting education and its curricula in Jordan. Third, the findings require urgent attention from the local policymakers (e.g., Jordanian Asso-ciation of Certified Public Accountants, and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Jordan) and inter-national policymakers (e.g., IFAC) to accommodate the model AIS curriculum.

This research has some limitations. First, we used a survey and interview methodology. However, more inter-views could be conducted in both private and public uni-versities. Furthermore, interviews with respondents from the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Education could demonstrate more detail about the gov-ernment’s agenda regarding the development of an AIS curriculum that complies with IFAC requirements. Sec-ond, some respondents did not fill in the questionnaire effectively. A broader and more complete coverage of all public and private universities in Jordan may be helpful for other developing countries that are noncomplying with IFAC requirements for AIS curriculum. Third, this study does not focus on the assessment of an AIS course. This suggests the need for future research to further explore this issue. Finally, future researchers should examine other accounting modules’ curricula and their relevancy with IFAC and professional accountancy bod-ies’ requirements.

TABLE 8

Model Course Learning Outcomes of AIS Course (Upon Successful Completion of this Course Students Should Be Able To. . .)

Sl

Learning domains and course learning outcomes

Course teaching strategies

Course assessment methods

A Knowledge

1 Define AIS and describe its basic functions and role in value chain. A combination of lectures, seminars and academic journals

Examinations, class tests/quiz

2 Describe the way information is stored in computer-based information systems;

A combination of lectures, seminars, computer-based workshops and academic journals

Assignment and examinations

B Cognitive skills

3 Evaluate the strengths and weakness of company’s internal control Case studies and ICT packages Class test/quiz, examinations 4 Analyze business problems through technical and conceptual

knowledge of accounting information systems

Computer-based workshops Assignments

C Interpersonal Skills & Responsibility

5 Write recommendations for improvements of companies internal control and ethics

Lectures, case studies, group discussions and academic journals

Examinations

6 Show the ability to work effectively as a member of a team on group assignments in relation to AIS

Group discussions and case studies Assignments

D Communication, Information Technology, Numerical

7 Prepare business reports using accounting information systems. A combination of lectures, seminars and ICT packages

Assignments

8 Document the company business process. A combination of lectures, seminars and computer-based workshops

Assignments and examinations

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the useful comments from the discussants at the 23rd Annual IBIMA Conference, Valen-cia, Spain, in 2014.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, N. S., & Gao, S. S. (2004). Changes, problems and challenges of accounting education in Libya.Accounting Education: An International Journal,13, 365–390.

Al-Akra, M., Ali, M. J., & Marashdeh, O. (2009). Development of accounting regulation in Jordan.The International Journal of Accounting,44, 163–186. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2008).The

AICPA core competency framework for entry into the accounting profes-sion. Retrieved from http://www.aicpa.org/interestareas/accountingedu cation/resources/pages/corecompetency.aspx

Andrews, C. P., & Wynekoop, J. (2004). A framework for comparing IS core curriculum and IS requirements for accounting majors.Journal of Information Systems Education,15, 437–450.

Bromson, G., Kaidonis, M. A., & Poh, P. (1994). Accounting information systems and learning theory: An integrated approach to teaching.

Accounting Education: An International Journal,3, 101–114.

Carnegie, G., & Napier, C. (2010). Traditional accountants and business professionals: Portraying the accounting profession after Enron.

Accounting, Organizations and Society,35, 360–376.

Chayeb, L., & Best, P. J. (2005). The accounting information systems cur-riculum: compliance with IFAC requirements. Proceedings Interna-tional Conference on Innovation in Accounting Teaching and Learning. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/5190/1/5190.pdf

Creswsell, J. W. (2007).Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choos-ing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Daigle, R. J., Hayes, D. C., & Hughes, K. E. II. (2007). Assessing student learning outcomes in the introductory accounting information systems course using the AICPA’s core competency framework. Journal of Information Systems,21, 149–169.

Davis, I. R., & Leitch, R. A. (1988). Accounting information systems courses and curricula: New perspectives.Journal of Information Sys-tems,3(1), 153–166.

De Lange, P., & Watty, K. (2011). Accounting education at a crossroad in 2010 and challenges facing accounting education in Australia. Account-ing Education: An International Journal,20, 625–630.

Er, M. C., & Ng, A. C. (1989). The use of computers in accountancy courses: a new perspective.Accounting and Business Research,19(76), 319–326.

Evans, E., Burritt, R., & Guthrie, J. (Eds.). (2010).Accounting education at a crossroad in 2010. Sydney, Australia: Centre for Accounting, Gover-nance and Sustainability, University of South Australia, Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia.

Flanagan, J., & Stewart, B. (1991, January).Assessing the value of employ-ing computers to enhance the learnemploy-ing process in accountemploy-ing education. Paper presented at the Second South East Asia University Accounting Teachers’ Conference, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Gallhofer, S., Haslam, J., & Kamla, R. (2009). Educating and training accountants in Syria in a transition context: perceptions of accounting

academics and professional accountants. Accounting Education: An International Journal,18, 345–368.

Groomer, S. M., & Murthy, U. S. (1996). An empirical analysis of the accounting information systems course.Journal of Information Systems,

10, 103–127.

Hastings, C. I., & Solomon, L. (2005). Technology and the accounting reg-ulation, curriculum: Where it is and where it needs to be.Advances in Accounting,21, 275–296.

Hunton, J. E. (2002). Blending information and communication technology with accounting research.Accounting Horizons,16, 55–67.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (1995).Information tech-nology in accounting curriculum, IFAC international education guide-line No. 11. New York, NY: Author.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2003).International edu-cation guideline 11: Information technology for professional account-ants. New York, NY: Author.

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2010). Handbook of international education pronouncements, 2010 edition. Retrieved from http://www.ifac.org/publications-resources/handbook-international-edu cation-pronouncements-2010-edition

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2012). International Accounting Education Standards Board’s (IAESB) terms of reference. Retrieved from http://www.ifac.org/education/about-iaesb/terms-refer ence

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation. (2014).

IFRS application around the world: Jurisdiction profile: Jordan. Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.org/Use-around-the-world/Documents/ Jurisdiction-profiles/Jordan-IFRS-Profile.pdf

Jackling, B., & de Lange, P. (2009). Do accounting graduates’ skills meet the expectations of employers? A matter of convergence or divergence. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 18, 369–385.

Kolb, D. A. (1984).Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Krippel, G., & Moody, J. (2007). Matching the international federation of

accountant’s international education guideline 11 To AIS textbooks: An examination of the current state of topic coverage.Review of Business Information Systems,11(4), 1–16.

McPeak, D., Pincus, K. V., & Sundem, G. L. (2012). The international accounting education standards board: Influencing global accounting education.Issues in Accounting Education,27, 743–750.

Preston, N. (1992). Computing and teaching: A socially-critical review.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,8, 49–56.

Romney, M. B., & Steinbart, P. J. (2014).Accounting information systems

(13th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Saville, H. (2007). International education standards for professional accountants (IESs). Accounting Education: An International Journal,

16, 107–113.

Strong, J. M., Portz, K., & Busta, B. (2006). A first look at the accounting information system emphasis at one university: An exploratory analysis. The Review of Business Information Systems,

10(2), 29–40.

Wessels, P. L. (2005). Critical information and communication technology (IT&C) skills for professional accountants. Meditari Accountancy Research,13, 87–103.

World Bank. (2004).Accounting and auditing: Hashemite kingdom of Jor-dan (JorJor-dan). Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.world bank.org/ifa/rosc_aa_jor.pdf

AIS CURRICULA DEVELOPMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH IFAC STANDARDS 357

APPENDIX: LIST OF UNIVERSITIES IN JORDAN (nD29)

Sl Name of the university Web address

Panel A: Public universities (nD10)

1 The University of Jordan www.ju.edu.jo

2 Yarmouk University www.yu.edu.jo

3 Mutah University www.mutah.edu.jo

4 Jordan University of Science & Technology www.just.edu.jo

5 The Hashemite University www.hu.edu.jo

6 AL al-Bayt University www.aabu.edu.jo

7 AL-Balqa Applied University www.bau.edu.jo

8 AL-Hussein Bin Talal University www.ahu.edu.jo

9 Tafila Technical University www.ttu.edu.jo

10 German Jordanian University www.gju.edu.jo

Panel B: Private universities (nD19)

11 Amman Arab University www.aau.edu.jo

12 Middle East University www.meu.edu.jo

13 Jadara University www.jadara.edu.jo

14 Al-Ahliyya Amman University www.ammanu.edu.jo

15 Applied Science University www.asu.edu.jo

16 Philadelphia University www.philadelphia.edu.jo

17 Isra University www.iu.edu.jo

18 Petra University www.uop.edu.jo

19 Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan www.alzaytoonah.edu.jo

20 Zarqa University www.zu.edu.jo

21 Irbid National University www.inu.edu.jo

22 Jerash University www.jpu.edu.jo

23 Princess Sumaya University for Technology www.psut.edu.jo

24 Jordan Academy of Music www.jam.edu.jo

25 Jordan Applied University College of Hospitality and Tourism Education (JAU) www.jau.edu.jo 26 Red Sea Institute of Cinematic Arts www.rsica.edu.jo

27 American University of Madaba www.aum.edu.jo

28 Ajloun National Private University www.anpu.edu.jo 29 University of Banking & Financial Sciences www.ubfs.edu.jo