Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Schooling in A Decentralised Indonesia: New

Approaches to Access and Decision Making

Mayling Oey Gardiner

To cite this article:

Mayling Oey Gardiner (2000) Schooling in A Decentralised Indonesia: New

Approaches to Access and Decision Making, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 36:3,

127-134

To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331339013

Published online: 18 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 95

View related articles

SCHOOLING IN A DECENTRALISED

INDONESIA: NEW APPROACHES TO ACCESS

AND DECISION MAKING

Mayling Oey-Gardiner

Insan Hitawasana Sejahtera, Jakarta

Thanks to a highly centralised supply-side policy in providing education services—through widespread construction of schools and rapid expansion of teacher recruitment and training—Indonesia has made remarkable progress in enrolling children in school and narrowing gaps between boys and girls. In 1971, among those of elementary school age (7–12), only about 60% were attending school. Figures for junior and senior high school aged children (13–15 and 16–18) were even lower, around 45% and 22% respectively. By 1999, according to special tabulations from the 1999 Susenas (National Socio-economic Survey), these figures had risen dramatically—to around 96% at ages 7–12, 79% at 13–15 and 51% at 16–18. Gender gaps, significant at secondary school ages in 1971, had virtually disappeared by the end of the 1990s.

However, gaps remain—between rural and urban areas and, perhaps even more critically, between the rich and the poor—and these gaps widen significantly with increases in schooling level. Thus the urban–rural gap in age-specific enrolment rates is relatively small among primary school age children (98% versus 94%). But it widens at junior secondary age (88% versus 74%) and becomes even wider for senior high school age children (69% versus 38%). Gaps between the rich and the poor are even more disturbing. Among primary school age children from the poorest quintile of households in 1999,1 92% were in school. Among the richest

quintile, the figure was 99%. At junior secondary ages the gap increases— 93% for the richest versus 66% for the poorest quintile. And at senior secondary ages it is even larger: 75% versus only 29% for the richest and poorest quintiles respectively (Insan Hitawasana Sejahtera 2000).

128 Mayling Oey-Gardiner

mobility. If the quality of this education is poor (as is widely believed to be true), their potential for upward mobility will be hindered even further. Second, a substantial number of children from wealthier families who should be able to afford the costs are still not carrying on through a full cycle of primary and secondary schooling. Many are joining the labour market while still at secondary school age. In fact, among school age children in the top quintile who are not attending school, one-fifth are working or seeking work, according to the 1999 data.

If even among the rich a good proportion attach so little value to available educational services in the country, it may be time for a serious examination of conditions in schools. This clearly relates not just to the quantity but also to the quality of education that is being provided, and to the roles of the public and the private sector. And concerns here are likely to rise in the near future as authority and responsibility for service delivery are devolved to local, district-level government under the new laws on regional autonomy and finance.2

A Closed System with Misplaced Quality Control

The educational drive in Indonesia has historically been highly centralised and ‘top-down’. Until recently, state school teachers across the country were central government employees, and their hiring and placement were determined by the centre—not by the districts or communities in which they worked. Determination of numbers of schools in various locations and funding for school construction came from the top. Fee structures (with the exception of parental contributions, administered by school bodies known as BP3) were also set at the national level.

Quality was seen, and is still seen by many, as being achieved through control and standardisation, with highly structured staffing patterns and curricula, and rigid rules governing both students and delivery of educational services. Children are required to progress through the system in an orderly fashion, with promotion being determined by performance at the previous level—be it school level or even grade within each school. No skipping of grades is allowed. And all students—in both public and private schools—are required to take nationally set examinations known as Ebtanas (Evaluasi Belajar Tahap Akhir Nasional, National School Leaving Examinations) that are intended to provide a consistent measure of student quality and to determine students’ potential for further progression in the education system.

Ebtanas examinations are held at the end of each school cycle—for elementary school at grade 6, and for both junior and senior high school at grade 3. Taking the examination is a requirement for graduation. A diploma cannot be issued by the school (and this applies to both public and private schools) unless the student has sat for the examination. Ebtanas is also a requirement for progression. Inability to show a certificate indicating that the student has taken the Ebtanas for the previous level prohibits a school from accepting that student, irrespective of whether the school is public or private. Thus neither schools nor students have the freedom to choose. Schools are simply forced to administer the examinations, while students must sit for them if they want to graduate or progress further in the education system.

The education bureaucracy defends Ebtanas as a means of controlling for variations in the quality of school level grading systems, and hence as a stimulus for schools to improve their quality. The examinations are also defended as a means to provide greater certainty in selection of students for progression to higher levels. To date, however, the validity of these suppositions has never been proven. In fact, examination scores appear to have little influence on graduation or school quality.

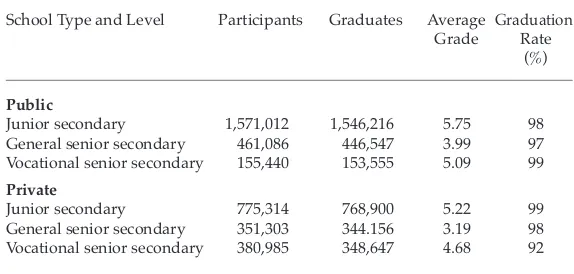

Grading of the national examinations is based on a scale from 0 to 10. But, as can be seen in table 1, average grades are generally quite low (on normal report cards, 6 is usually considered a minimum passing grade), while graduation rates remain very high, all well in excess of 90%. The

TABLE 1 Low Final Examination Scores but High Graduation Rates, 1998/99

School Type and Level Participants Graduates Average Graduation Grade Rate

(%)

Public

Junior secondary 1,571,012 1,546,216 5.75 98 General senior secondary 461,086 446,547 3.99 97 Vocational senior secondary 155,440 153,555 5.09 99

Private

Junior secondary 775,314 768,900 5.22 99 General senior secondary 351,303 344.156 3.19 98 Vocational senior secondary 380,985 348,647 4.68 92

130 Mayling Oey-Gardiner

worst cases are among general senior high school students, who managed to score on average less than 4 on Ebtanas in 1998/99 (table 1). Yet 97–98% still graduated. This relationship, or absence of one, has never been examined. Instead, the bureaucracy has defended the system, while civil society has remained helpless, unable to ignore this requirement.

Clearly, Ebtanas provides little or no control over the quality of graduates. The policy of requiring students to sit for the examination, in addition to normal school testing and grading, in order to graduate must thus be open to question. The low scores, and questions that have been raised over just what the tests are measuring (not to mention frequent allegations related to leakage of examination materials and manipulation of scores), cast doubt on its value as a screening tool for progression to higher levels in the education system. If screening beyond grades and other school-based performance measures is required, it would probably be far more efficient for testing of prospective students to be carried out by individual schools, using whatever standards they deem necessary. For state universities, where selection is a major issue, there is already a separate entrance examination, the UMPTN (Ujian Masuk Perguruan Tinggi Negeri, State Higher Education Entrance Examination), that is used as a basis for screening applicants.3 Some more elite high schools

require applicants to take special aptitude tests, either designed by the school or through private testing services.

Vested Interests in Maintaining the System

Without taking the examination students are not allowed to graduate, and without the piece of paper indicating their examination scores they cannot progress to the next level in the education hierarchy or apply for a job in the civil service. Thus parents have no choice but to pay the examination fees if they want their children to have a chance at further education, or even simply proof of completion at their current level.

And these payments are substantial. For example, official fees for secondary level Ebtanas in Jakarta are generally two or more times official monthly fees for public school attendance.4 They also provide a

substantial windfall to administrators. For the 1999/2000 academic year end examinations, the Jakarta government avoided giving a total budget (stating expenditures only on a per student basis). However, multiplying per student fees by an expected number of participants suggests that total returns would probably reach at least Rp 22 billion, or close to $3 million.5 Around 42% of this budget was allocated to administration,

been legitimate, but there were substantial amounts allowed for meetings and honoraria that must be questioned, given that the participants were salaried government officials.

These concerns have been echoed in the press, with several reports on the amounts of money involved, as well as on the hardships these imposed on students and their families (Kompas, 22/5/00 and 23/5/00;

Media Indonesia, 23/5/00). Articles have also reflected an increasingly widespread view in favour of eliminating the Ebtanas altogether (Kompas, 24/5/00 and 25/5/00; Suara Pembaruan, 23/5/00). Yet, given the overall amount of money involved, it should not be surprising that the vested interests in maintaining the system are very strong.

New Initiatives in Access and Decision Making

However, some initiatives are being taken to improve educational access and decentralise decision making. For instance, in response to the crisis the government, with loans from the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, has established an educational social safety net program to prevent an increase in school dropouts. This program provides scholarships to poor students and operational funds for poor schools, known as DBO (Dana Bantuan Operasional). These are distributed directly to the beneficiary students and schools, thereby avoiding possible ‘leakage’ along the way. The program has been hailed as successful, earning a World Bank award.

In response to a World Bank education sector analysis (World Bank 1998), Dr Fasli Djalal of Bappenas took the initiative to have Indonesian researchers conduct further analysis of the implications of the crisis and of impending moves toward greater decentralisation and regional autonomy. An initial group of studies led to the formation of four task forces that were approved for ASEM (Asia Europe Meeting) funding administered by the World Bank. These task forces covered philosophy, teachers, higher education, and educational finance.

132 Mayling Oey-Gardiner

The vision contained in this study was to move from quantity (equity) to quantity and quality; and from a supply to a demand orientation—the argument being that, if properly managed under the supervision of school boards and school committees, schools will be in the best position to decide what they need and what they can achieve. School boards would oversee a number of schools in an area, and would consist of non-salaried members who are political appointees selected by the local community. The boards would be responsible for preparing selection criteria for teachers and students, and for selecting independent institutions to conduct school performance audits. They would also decide on subsidy recipients and allocation of subsidies to schools. School committees would operate at individual school level. They would consist of parents and teachers, including school principals, but school principals would not be able to become chairpersons, and all members would have equal voting rights. Of course, each school committee would be required to make its decisions transparent and to be accountable to all parents and teachers of the school. There is already in place a precursor of school committees, known as BP3 (Badan Pembinaan dan Penyelenggaraan Pendidikan, Board of Educational Development and Administration), but so far these have had only a limited role, deciding on issues such as school uniforms, and setting the level of parental contributions (JP, 31/7/00).

Even if there is now fairly widespread consensus about the poor quality of Indonesian schools, there is still debate about how to remedy it. The views expressed above have not yet achieved wide acceptance, and there are many who still believe that quality can be imposed by central control and rigid common standards. There also are many who see the roots of low quality in low teacher salaries and poor teacher training. This may be part of the problem, but it begs the even more critical question of just what the schools and students will get in return for a higher investment in education. How will teachers, schools and the education system in general be held accountable for the investments that are made?

Some Official Responses to New Ideas

evaluate its implementation (Suara Pembaruan, 7/7/00), and the head of the Ministry’s Research and Development Office said that Ebtanas might even be replaced (JP, 22/7/00).

In contrast with its past adherence to an ideology of equity in a centralised and standardised system, the Ministry of National Education now acknowledges that difference is not necessarily a bad thing, including difference in the quality of schools. In an important move to relax past rigidities in the curriculum, and to begin to allow choice at school level, in 2001 schools will be offered the freedom to choose one of three curricula. These are structured at novice, intermediate and expert levels, and are designed to give schools greater flexibility to adapt their programs to their own capabilities and those of their students. This will apply to schools throughout the country, whether public, private or religious. The emphasis is on output, with basic minimum standards having to be fulfilled by graduates no matter which curriculum their school adopts. Schools will also have greater flexibility in deciding on appropriate teaching methods, books and other technical materials. The Ministry will only provide references (JP, 22/7/00).

More encouraging, the head of the Jakarta office of the education ministry stated that parent–teacher bodies (school committees) will have greater power under regional autonomy, beyond just deciding on school uniforms and setting fees (Suara Pembaruan,26/7/00). Attempts will be made to involve parents more, including in decisions about the quality of services provided by the respective schools. However, only time will tell what the bureaucracy is really willing to give up, and where parents may have greater authority over school operations.

NOTES

1 These figures are based on special tabulations of the 1999 Susenas, classifying households into expenditure quintiles based on reported total monthly per capita household expenditure.

2 Laws No. 22 and 25 of 1999 on Regional Autonomy and Regional Finance are scheduled to begin formal implementation in January 2001.

134 Mayling Oey-Gardiner

5 Just under 300,000 students took secondary level Ebtanas in 1998/99. 6 The idea of school-based management and activities to further this objective

is not new in Indonesia. However, I believe that this is the first time a recommendation has been made for the ‘radical’ option, covering not only the development budget but also the routine budget for staff salaries, and including the right to manage the teaching staff.

REFERENCES

Burki, Shahid Javed, Guillermo E. Perry and William R. Dillinger (1999), Beyond the Centre: Decentralizing the State, World Bank, Washington DC.

Insan Hitawasana Sejahtera (2000), Provincial Poverty and Social Indicators,

Susenas1993–1999, Report submitted to the Asian Development Bank, Manila. Jimenez, Emmanuel, Vincente Paqueo and Lourdes de Vera Ma (1988), ‘Does Local Financing Make Primary Schools More Efficient? The Philippine Case’, World Bank Policy Planning and Research Working Papers, Education and Employment, WPS 69, World Bank, Washington DC.

King, Elizabeth M., and Berk Ozler (1998), What’s Decentralization Got To Do With Learning? The Case of Nicaragua’s School Autonomy Reform, Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego CA, 13–17 April.

Patrinos, Harry Anthony, and David Laksmanan Ariasingam (1997),

Decentralization of Education: Demand-Side Financing, The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, June, Washington DC.