www.elsevier.nlrlocateraqua-online

Influence of egg size on growth and survival of

early stages of Siberian sturgeon

ž

Acipenser baeri under small scale hatchery

/

conditions

E. Gisbert

a,), P. Williot

b, F. Castello-Orvay

a´

a

Laboratori d’Aquicultura, Departament de Biologia Animal, Facultat de Biologia, Uni¨ Õersitat de Barcelona,

AÕ. Diagonal, 645, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

b

Cemagref, Groupement de Bordeaux, 50 aÕenue de Verdun, 33611 Gazinet Cedex, France

Accepted 6 August 1999

Abstract

A study was conducted to determine the relationships between egg and newly hatched larvae

Ž .

sizes and growth and survival of Siberian sturgeon Acipenser baeri during early stages of

development. We hypothesised that this may lead to improved rearing techniques and hatchery

Ž .

management. Eggs mean size 2.8–4.1 mm were obtained from 20 cultured 13–14 years old

Ž .

females. There was a positive correlation between egg size and total length TL , body weight

ŽBW and yolk sac volume of newly hatched larvae. Mortality during the endogenous feeding.

phase were less than 3.6% and occurred among morphologically deformed fish. First feeding age

Ž9–11 days post-hatch correlated significantly with egg and newly hatched larvae size P. Ž -0.05 ..

At the onset of the exogenous feeding, mortality sharply increased in all experimental groups and represented 2.1%–23.5%. Losses were attributed to the change from endogenous nutrition to exogenous feeding based on an artificial commercial diet. Cannibalism was common between 9

Ž .

and 15 days post-hatch, but was not an important source of larval mortality 2.0%–5.4% . Mortality substantially declined after the transition to exogenous feeding. At the end of the rearing

Ž .

period 20 days post-hatch , the effects of egg and newly hatched larvae sizes were still evident on

Ž . Ž .

the TL and BW of larvae P-0.05 . However, no significant differences P)0.05 were found

Ž .

when larval specific growth rates SGRs were compared between progeny from different females, revealing the ability of smaller specimens of Siberian sturgeon to grow at the same rate as initially

Ž .

larger fish. Egg size did not provide any advantage for survival of young fish P)0.05 . We

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q34-934-021-447; fax:q34-934-021-93; e-mail: [email protected] 0044-8486r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

conclude that under generally favourable rearing conditions, egg size has no direct implications for larval survival of Siberian sturgeon.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Siberian sturgeon; Acipenser baeri; Larvae; Mortality; Growth; Egg size

1. Introduction

Sturgeon fingerling production is considered to be one of the most difficult phases of hatchery rearing. Egg size and development may affect their quality, ability to produce viable larvae, and to some extent directly determine growth and survival of young fish

ŽHeming and Buddington, 1988; Kjorsvik et al., 1990 . Under artificial conditions, once.

larvae hatch from the egg and deplete their intraembryonic yolk sac reserves, their survival depend on multiple factors, such as the nutritional input, rearing system design

Ž .

and hatchery management Conte et al., 1988 . Early life stages of development are some of the most important phases of fish development, which include the replacement

Ž

of embryonic adaptations and functions e.g., yolk sac nutrition and cutaneous

respira-. Ž .

tion by definitive ones e.g., exogenous feeding and branchial respiration . Such

Ž

adaptations alter the relationship of the developing fish with the environment Dettlaff et

.

al., 1993 , and these changes can directly affect growth and survival of young speci-mens.

Mortality of acipenserids during embryonic and larval development is of considerable

Ž

importance Buddington and Christofferson, 1985; Gisbert and Williot, 1997; Bardi et

.

al., 1998 . As a result, substantial efforts were focused on the early life developmental stages of this group of fishes in order to understand how to increase their survivorship and improve hatchery efficiency. While there are several studies on growth and survival

Ž

of Siberian sturgeon larvae under different experimental conditions Evgrafova et al., 1982; Semenkova, 1983; Dabrowski et al., 1985; Charlon and Bergot, 1991; Gisbert and

.

Williot, 1997 , little information is available on larval mortality and whether larger egg and newly hatched larvae sizes provide any advantage for growth and survival of young fish. This information would be useful to fish farmers for estimating fingerling produc-tion, to improve rearing techniques and for hatchery management and evaluation of the

Ž .

quality of fish produced Krasnodembskaya, 1993 .

The objective of the study was to examine the relationships between egg and newly hatched larvae sizes, growth and survival of young Siberian sturgeon.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Supply and maintenance of sturgeon larÕae

This experiment was carried out in a flow-through freshwater system at the Centre de

Ž .

Recherche Aquacole C.R.E.A., Cemagref, France during 1997 and 1998. Siberian sturgeon larvae were obtained by induced spawning of 20 13–14 years old cultured

Ž .

Ž .

randomly chosen from those with the highest reproductive potential Williot, 1997 . In the study, parental fish of the same strain and geographic location were used to avoid

Ž .

difficulties in interpreting results Springate and Bromage, 1985 . After eliminating egg

Ž .

adhesiveness Conte et al., 1988 , eggs were incubated in a closed thermoregulated and UV-treated freshwater system at 138–158C. After 7 days of incubation, the fish hatched.

Ž

In each case, a group of 2700 newly hatched Siberian sturgeon larvae 1 day

. Ž 3

post-hatch were randomly distributed into two grey plastic troughs 1.5=0.5=0.07 m

. Ž .

deep at a density of 30 larvaerl 1350 larvaertrough according to Gisbert et al.

Ž1999 . Troughs used in the study were approximately half the size as those used in.

commercial hatcheries. Siberian sturgeon larvae were initially fed at the age of 9 days

Ž . Ž

after hatching at a feeding rate of 15% body weight BW per day Gisbert and Williot,

.

1997 . This feeding rate was reduced to 10% when fish were 15 days post-hatch and

Ž .

maintained at this level until the end of the rearing period 20 days post-hatch . The fish

Ž

were fed a dry commercial diet ‘‘Lansy A2 and W3’’, Artemia Systems, Gent,

. Ž

Belgium . Feed was delivered during the day by automatic feeders conveyor belt

.

system , and only interrupted during cleaning times. Initiation of feeding was deter-mined by means of visible indications of feeding such as distended stomachs and

Ž

characteristic internal coloration associated with the dry commercial diet used Lutes et

.

al., 1990 .

Troughs were cleaned three times daily, at 0800–0900, 1400–1500 and 1900–2000 h to remove uneaten food and faeces. Fish were inspected daily for abnormal behaviour

Ž . Ž . Ž

and mortality. Water temperature, dissolved oxygen DO YSI model 57 , pH Schott

. Ž .

Gerate model CG817T , conductivity WTW LF 196 and flow rate were measured daily throughout the rearing period. Water temperature, DO, pH, conductivity and flow rate

Ž

were 18.0"0.38C, 8.7"0.2 mgrl, 7.7"0.1, 367"0.6mSrcm, 3.9"0.4 lrm mean

.

"S.E. , respectively. Fish were exposed to a 12-h light–dark photoperiod using overhead fluorescent lights.

2.2. Egg size, larÕae growth and surÕiÕal measurements

Ž .

As Siberian sturgeon eggs have an ovoidal shape Dettlaff et al., 1993 , the egg

Ž .

diameter mm was calculated as the arithmetical mean between the maximum and minimum egg diameters. Egg diameter was determined under a dissection microscope

Ž .

with a micrometer eyepiece Leica Wild MPS 52 . A sample of 100 eggs from each female after stripping was used per observation.

At hatch, 30 larvae were randomly sampled from each batch of eggs and their BW

Ž .

and total length TL were measured to the nearest milligram and millimeter, respec-tively. Length measurements were performed by means of a dissection microscope with

Ž 3.

a micrometer eyepiece. The volume mm of the ellipsoidal larval yolk sac at hatching

Ž .

was calculated using the following formula Heming and Buddington, 1988

Vs0.1667pLH2

where H is the height and L is the length of the yolk sac mass.

Ž .

rearing. TL and BW were measured. Specific growth rate SGR was calculated for

Ž .

different developmental stages using the following formula Dabrowski et al., 1985

SGR % day

Ž

y1.

s100=Ž

ln Wyln W.

rt ;t o

where W and W represent final and initial mean BWs and t the growing period in days.t o

Mortality was recorded daily and final survival was determined by hand-counting all

Ž .

surviving fish at the end of the trial 20 days post-hatch for each experimental trough.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Ž .

Survival and SGR with arcsin square root transformed data of larvae, and BW, TL and yolk sac volume of Siberian sturgeon larvae from different females were subjected

Ž .

to the analysis of variance variables normally distributed, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test

ŽZar, 1974 . When a significant difference was detected P. Ž -0.05 , the ANOVA was.

followed by a Turkey’s multiple-range test to identify which treatments were signifi-cantly different. Variables were correlated initially by means of the Pearson product

Ž .

moment correlation SigmaStat, 1995 . When a statistically correlationship was detected between two variables, data were analysed by means of linear regression.

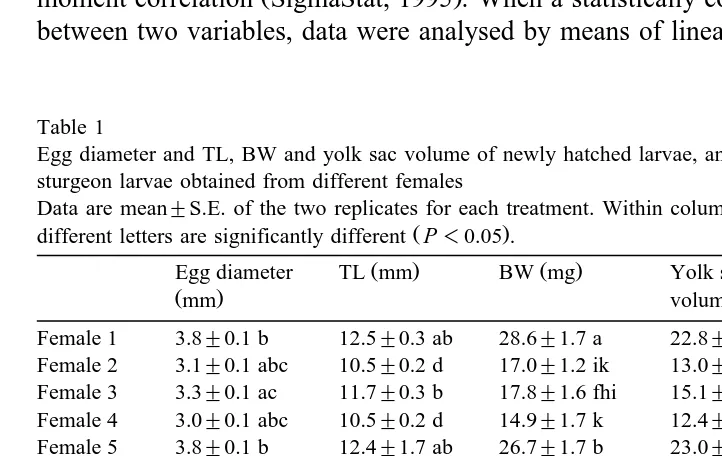

Table 1

Egg diameter and TL, BW and yolk sac volume of newly hatched larvae, and age at first feeding of Siberian sturgeon larvae obtained from different females

Data are mean"S.E. of the two replicates for each treatment. Within columns, treatment means followed by

Ž .

different letters are significantly different P-0.05 .

Ž . Ž .

Egg diameter TL mm BW mg Yolk sac Age of first

3. Results

Data on egg diameter, newly hatched larvae size in length and weight, yolk sac volume and the age at first feeding of Siberian sturgeon larvae obtained from different females are reported in Table 1. At hatching, there was a positive and significant

correlation between egg size, which varied from 2.8 to 4.1 mm in diameter and TL

Žrs0.81; P-0.001; ns20 , BW r. Ž s0.88; P-0.001; ns20 and yolk sac volume.

Ž . Ž .

of newly hatched larvae rs0.92; Ps0.004; ns20 Fig. 1 . During the endogenous feeding phase, between hatching and 9–11 days post-hatch, cumulative mortality was

Ž . Ž .

different between different groups of larvae P-0.05 and was 0.2%–3.6% Table 2 . No significant correlation was found between eggs size and survival during the stage of

Ž .

endogenous nutrition P)0.05 . Dead larvae during this period had some severe morphological malformations such as hydrocele in the abdominal cavity, heart tube left-side bent or without bending, thinning and breaking of yolk sac walls, twisted body and underdeveloped tail myomeres.

Depending on the maternal origin, first feeding in Siberian sturgeon was observed

Ž

between 9 and 11 days post-hatch and was correlated with mean egg diameter rs0.63;

. Ž

Ps0.004; ns20 , and with newly hatched larvae size in length rs0.72; Ps0.003;

. Ž . Ž .

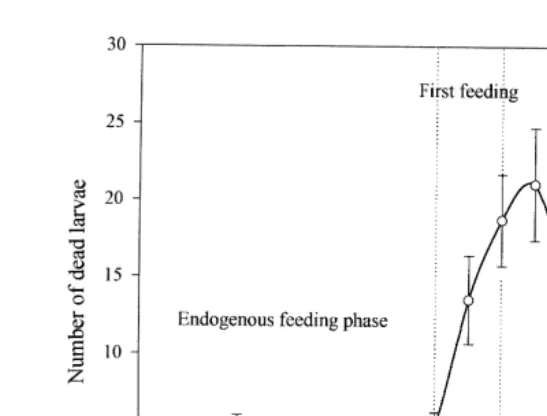

ns20 and weight rs0.66; Ps0.002; ns20 Fig. 1 . At the beginning of

Ž

exogenous feeding, mortality sharply increased in all experimental rearing troughs Fig.

.

2 . Depending on maternal origin, losses represented 2.1%–23.5% of the total mortality. During this period, 70%–75% of the dead larvae had food in their stomachs. Significant differences were detected between mortality of larvae obtained from different females

ŽP-0.05 . Mortality rates detected during the endogenous feeding phase were not.

Ž .

correlated with mortality rates observed during the exogenous feeding period P)0.05 .

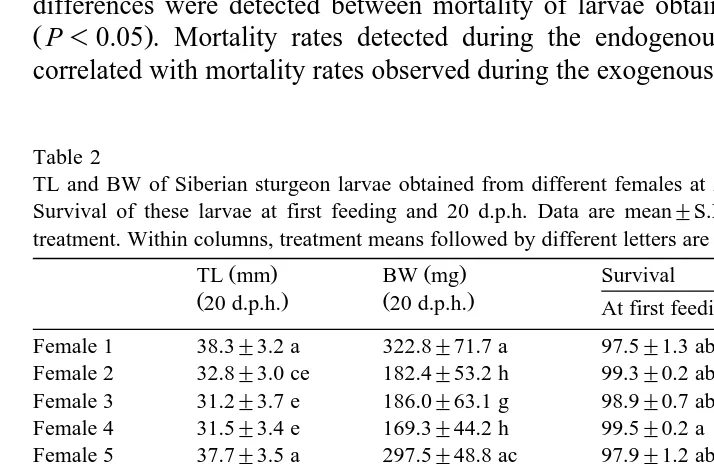

Table 2

Ž .

TL and BW of Siberian sturgeon larvae obtained from different females at 20 days after hatching 20 d.p.h. Survival of these larvae at first feeding and 20 d.p.h. Data are mean"S.E. of the two replicates for each

Ž .

treatment. Within columns, treatment means followed by different letters are significantly different P-0.05 .

Fig. 2. Daily numbers of dead Siberian sturgeon larvae obtained from 20 different females. Dotted line represents the period of transition to exogenous feeding. Data are mean numbers per tank and standard deviation.

Between the onset of the exogenous feeding and 15 days after hatching, many dead

Ž

larvae showed signs of cannibalism e.g., damaged pectoral fins, abdominal cavity,

.

barbillons andror opercula . Cannibalism was observed among all experimental groups

Ž2%–5.4% of total losses . After the transition to exogenous feeding, mortality de-.

Ž .

creased dramatically Fig. 2 . During this period, some larvae were observed with slight malformations, such as underdeveloped opercula, no joining of the olfactory septum, or unpigmented eyes; however, these morphological malformations did not seem to affect

Fig. 3. Linear regression equations and relationship between egg diameter and size in length and weight of

Ž .

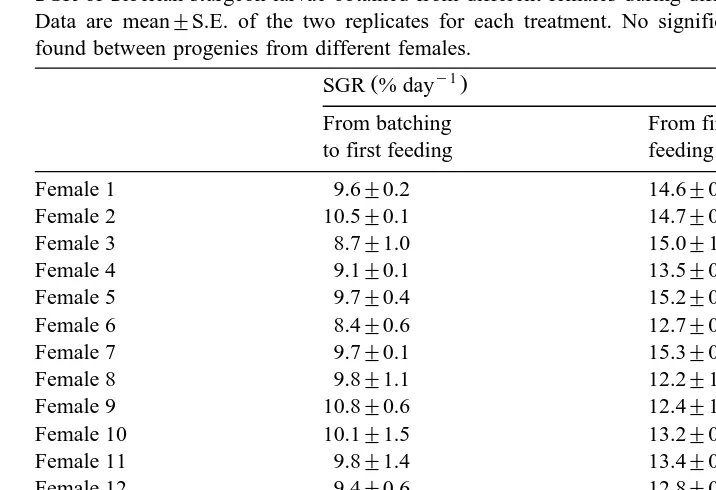

Table 3

SGR of Siberian sturgeon larvae obtained from different females during different rearing periods

Ž .

Data are mean"S.E. of the two replicates for each treatment. No significant differences P)0.05 were found between progenies from different females.

y1

Ž .

SGR % day

From batching From first

to first feeding feeding to 20 d.p.h.

Female 1 9.6"0.2 14.6"0.2

larval survival. No signs of myxobacteriosis nor columnariosis were observed after first feed administration in any of the experimental groups.

Larval BW ranged from 322.8 to 159.4 mg and TL ranged from 38.3 to 30.1 mm at

Ž . Ž .

the end of the analysed period 20 days after hatching Table 2 . At this age, the effect of egg size on larval growth was still evident: larval BW and TL were correlated with

Ž .

egg diameter rs0,73; P-0.001; ns20; rs0,67; Ps0.001; ns20; respectively

ŽFig. 3 . Although there were differences in final BW and TL of larvae from different.

Ž .

source females P-0.05 , SGRs were similar among different sources of larvae during

Ž . Ž .

the examined period P)0.05 Table 3 . No correlation was found between egg size

Ž .

and SGR for different developmental stages P)0.05 . No statistically significant

Ž .

correlation was found between survival at first feeding and at 20 days post-hatch and the egg size and yolk sac volume of newly hatched larvae, BW and TL of newly hatched

Ž .

larvae and larvae aged 20 days post-hatch P)0.05 .

4. Discussion

This study showed that Siberian sturgeon larvae hatched from larger eggs were larger

Ž .

in size TL, BW and yolk sac volume than those from smaller eggs. These results are in

Ž

. Ž

harengus; Blaxter and Hempel, 1963 , Atlantic salmon Salmo salar; Thorpe et al.,

. Ž .

1984 , Arctic charr SalÕelinus alpinus; Wallace and Aasjord, 1984 , rainbow trout

ŽOnchorhynchus mykiis; Springate and Bromage, 1985 and Iceland cod Gadus morhua;. Ž .

Marteinsdottir and Steinarsson, 1998 . In addition, the initial feeding time of Siberian sturgeon larvae was positively correlated with egg size. Under these rearing conditions, the onset of exogenous feeding was detected between 9 and 11 days post-hatch, depending on the egg size. Thus, larvae hatched from larger eggs tended to delay the onset of exogenous feeding. In natural environments, these fish would survive longer

Ž .

without food than those hatched from smaller eggs Kjorsvik et al., 1990 . At the end of

Ž

the rearing period, the effect of egg size was still evident in larval size length and

.

weight ; however, these correlations between egg diameter and fish size disappeared

Ž . Ž .

during the juvenile stage unpublished data . Wallace and Aasjord 1984 found that the effect of egg size on the length of Arctic charr alevins was still clearly evident 140 days

Ž .

after hatching. Glebe et al. 1979 working with Atlantic salmon reported that the length of fry was still related to the original egg diameter some 8 months later. However,

Ž .

according to Kjorsvik et al. 1990 , it seems doubtful that egg size provides any permanent or long-term advantages as far as growth and survival of fish larvae are concerned.

Our results showed no significant differences in larval SGR between progeny from different females. Thus, smaller larvae were able to grow at the same relative rate as

Ž

initially larger larvae, which is of considerable importance Heming and Buddington,

.

1988 . Our study also revealed that egg size of Siberian sturgeon did not provide any advantage as far as survival of young fish was concerned. Under favourable conditions, it has been shown that egg size has no direct implications for larval survival in some

Ž .

other species, such as rainbow trout Pitman, 1979; Springate and Bromage, 1985 ,

Ž . Ž

Atlantic salmon Thorpe et al., 1984 , catfish Clarias macrocephalus; Reagan and

. Ž .

Conley, 1977 , and carp Cyprinus carpio; Zonova, 1973; Tomita et al., 1980 .

Ž .

Springate and Bromage 1985 suggested that where size-dependent survival rates were reported, the results might actually reflect a difference between stage of ripeness of eggs, rather than egg size.

Mortality was found independent of the source female and egg size. Less than 2.5% of total mortality occurred during the endogenous feeding phase and this was due to

Ž

severe morphological malformations e.g., hydrocele in the abdominal cavity, heart tube malformations, thinning and breaking of yolk sac walls, twisted body and undeveloped

.

tail myomeres . Mortality rates after first feeding were 2.1%–23.5% of the total mortality and mainly occurred between 9 and 18 days post-hatch, depending on the source female. Working with the same species, similar results have been also reported

Ž . Ž .

by Charlon and Bergot 1991 and Gisbert and Williot 1997 examining a pool of

Ž

specimens obtained from fewer females. This is a critical stage of development Heming

.

and Buddington, 1988 as larval survival is ultimately dependent on the availability of sufficient high quality foods after yolk sac reserves are exhausted. Thus, there are selective pressures synchronising the completion of yolk absorption and the capability of

Ž .

feeding Heming and Buddington, 1988 .

Mortality due to starvation sharply increases between 15 and 19 days post-hatch in

Ž .

observed mortality is most likely caused by the change from endogenous to exogenous feeding. Such observations are in agreement with other studies that reported important

Ž

losses at a similar stage of development Semenkova, 1983; Buddington and Doroshov,

.

1984; Charlon and Bergot, 1991 . The differences in mortality rates between this and other published studies can be attributed to the different fish husbandry, origin, and the quality of feed. Nowadays, commercial non-purified rainbow trout diets and starter

Ž

marine fish diets are commonly used to raise young sturgeons Hung, 1991; Gisbert and

.

Williot, 1997; Bardi et al., 1998 . However, such diets are considered suboptimal because prolonged feeding of sturgeon with them results in severe malformations and

Ž .

physiological disorders that are suspected to be nutritionally related Hung, 1991 . Hence, losses at this stage of transition to an artificial diet could be reduced if a manufactured commercial diet for sturgeons was developed.

Cannibalism is a common behaviour during the period of transition to exogenous

Ž

feeding in acipenserid species Dabrowski et al., 1985; Charlon and Bergot, 1991;

.

Krasnodembskaya, 1993 . Cannibalized larvae typically have their pectoral fins, barbels, opercula, abdominal cavity or tail damaged, thus, making them more susceptible to potential bacterial infections. The combination of cannibalism and bacterial growth, due to the presence of uneaten feed, can result in a significant larval mortality during this period of transition between yolk sac nutrition and external feeding. Although cannibal-ism has not been reported as an important source of mortality during rearing of Siberian

Ž .

sturgeon larvae Gisbert and Williot, 1997; this study , unsuitable management, such as inadequate feed quantity and quality, periods of food deprivation after yolk sac resorption and excessive stocking density can result in a high level of cannibalism

ŽCharlon and Bergot, 1991; Krasnodembskaya, 1993 ..

In conclusion, the effect of egg size was still evident at the end of the larval stage; however, egg size did not provide any advantage as far as survival of young specimens was concerned. For Siberian sturgeon, egg size has no direct implications in overall larval quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to R. Brun, M. Pelard, D. Mercier and T. Rouault

ŽCemagref for rearing adult fish and their help and assistance during the study. E..

Ž .

Gisbert was supported by a F.I. grant FI-PG 95-1.144 from the Generalitat de

Ž .

Catalunya Spain .

References

Bardi, R.W., Chapman, F.A., Barrows, F.T., 1998. Feeding trials with hatchery produced Gulf of Mexico sturgeon larvae. Prog. Fish-Cult. 60, 25–31.

Ž .

Blaxter, J.H.S., Hempel, G., 1963. The influence of egg size on herring larvae Clupea harengus . J. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer. 28, 211–240.

Buddington, R.K., Christofferson, J.P., 1985. Digestive and feeding characteristics of the chondrosteans.

Ž .

Buddington, R.K., Doroshov, S.I., 1984. Feeding trials with hatchery produced white sturgeon juveniles

ŽAcipenser transmontanus . Aquaculture 36, 237–243..

Ž

Charlon, N., Bergot, P., 1991. Alimentation artificielle des larves de l’esturgeon siberien Acipenser baeri,

. Ž .

Brandt . In: Williot, P. Ed. , Proceedings of the First International Symposium on the Sturgeon, CEMAGREF, Bordeaux, France, pp. 405–415.

Conte, F.S., Doroshov, S.I., Lutes, P.B., Strange, E.M., 1988. Hatchery manual for white sturgeon, Acipenser

transmontanus R., with application to other North American Acipenseridae. Div. Agric. Nat. Res.,

University of California, Oakland, CA, 104 pp.

Ž .

Dabrowski, K., Kaushik, S.J., Fauconneau, B., 1985. Rearing of sturgeon Acipenser baeri, Brandt larvae: I. Feeding trial. Aquaculture 47, 185–192.

Dettlaff, T.A., Ginsburg, A.S., Schmalhausen, O.I., 1993. Sturgeon Fishes. Developmental Biology and Aquaculture. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 300 pp.

Evgrafova, V.N., Drobysheva, E.B., Semenkova, T.B., 1982. The rearing of Siberian sturgeon juveniles on

Ž .

different diets. Rybn. Khoz. Moscow 2, 37–38, in Russian.

Gisbert, E., Williot, P., 1997. Larval behaviour and effect of the timing of initial feeding on growth and survival of Siberian sturgeon larvae under small scale hatchery production. Aquaculture 156, 63–76. Gisbert, E., Williot, P., Castello-Orvay, F., 1999. Behavioural modifications in the early life stages of Siberian´

Ž .

sturgeon Acipenser baeri, Brandt . J. Appl. Ichthyol. 15, 237–242.

Ž .

Glebe, B.D., Appy, T.D., Saunders, R.L., 1979. Variation in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar . ICES CM

1979rM 23, 11 pp.

Heming, T.A., Buddington, R.K., 1988. Yolk sac absorption in embryonic and larval fishes. In: Hoar, W.A.,

Ž .

Randall, D.J. Eds. , Fish Physiology, Vol. 11A. Academic Press, London, pp. 407–446.

Ž

Hung, S.S.O., 1991. Nutrition and feeding of hatchery-produced juvenile white sturgeon Acipenser

transmon-. Ž .

tanus : an overview. In: Williot, P. Ed. , Proceedings of the First International Symposium on the

Sturgeon, CEMAGREF, Bordeaux, France, pp. 65–77.

Kjorsvik, E., Mangor-Jensen, A., Holmefjord, I., 1990. Egg quality in fishes. Adv. Mar. Biol. 26, 71–113. Krasnodembskaya, K.D., 1993. Adaptations of sturgeon larvae in relation to problems of sturgeon culture. In:

Ž .

Gershanovich, A.D., Smith, T.I.J. Eds. , International Symposium on Sturgeons. Abstract Bulletin, Moscow, VNIRO, p. 76.

Lutes, P.B., Hung, S.S.O., Conte, F.S., 1990. Survival, growth and body composition of white Sturgeon larvae fed purified and commercial diets at 14.7 and 18.48C. Prog. Fish-Cult. 52, 192–196.

Marteinsdottir, G., Steinarsson, A., 1998. Maternal influence on the size and viability of Iceland cod Gadus

morhua eggs and larvae. J. Fish Biol. 52, 1241–1258.

Pitman, R.W., 1979. Effects of female age and size on growth and mortality in rainbow trout. Prog. Fish-Cult. 41, 202–204.

Reagan, R.E., Conley, C.M., 1977. Effect of egg diameter on growth of channel catfish. Prog. Fish-Cult. 39, 133–134.

Semenkova, T.B., 1983. Growth, survival and physiological indices of juvenile Lena River sturgeon,

Ž .

Acipenser baeri stenorhynchus Nikolsky, grown on food ‘‘Ekvizo’’. In: Ostroumova, I.N. Ed. , Problems

of Fish Physiology and Nutrition. Ministry of Fish Management, Leningrad, No. 194, pp. 107–111, in Russian.

SigmaStat, 1995. User’s Manual SigmaStat, Statistical Software, Version 2.0 for Windows 95, WT and 3.1, Jandel.

Springate, J.R.C., Bromage, N.R., 1985. Effects of egg size on early growth and survival in rainbow trout

ŽSalmo gairdneri Richardson . Aquaculture 47, 163–172..

Thorpe, J.E., Miles, M.S., Keay, D.S., 1984. Developmental rate, fecundity and egg size in Atlantic salmon,

Salmo salar L. Aquaculture 43, 289–305.

Tomita, M., Iwahashi, M., Suzuki, R., 1980. Number of spawned eggs and ovarian eggs and egg diameter and percent eyed eggs with reference to the size of the female carp. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 46, 1077–1081. Wallace, J.C., Aasjord, D., 1984. An investigation of the consequences of the egg size for the culture of Arctic

Ž .

charr SalÕelinus alpinus . J. Fish Biol. 24, 427–435.

Ž .

Williot, P., 1997. Reproduction de l’esturgeon siberien´ Acipenser baeri Brandt en elevage: gestion des´

genitrices, competence a la maturation in vitro de follicules ovariens et caracteristiques plasmatiques durant´ ´ ` ´

Williot, P., Brun, R., Rouault, T., Rooryck, O., 1991. Management of female spawners of Siberian sturgeon,

Ž .

Acipenser baeri Brandt: first results. In: Williot, P. Ed. , Proceedings of the First International

Sympo-sium on the Sturgeon, CEMAGREF-DICOVA, Bordeaux, pp. 365–379.

Ž .

Zar, J.H., 1974. In: McElroy, W.D., Swanson, C.P. Eds. , Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 718 pp.

Ž

Zonova, A.S., 1973. The connection between egg size and some of the characters of the female carp Cyprinus

.