Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 20:02

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

THE PROMISE AND THE PERIL OF MICROFINANCE

INSTITUTIONS IN INDONESIA

Jay K. Rosengard , Richard H. Patten , Don E. Johnston Jr & Widjojo

Koesoemo

To cite this article: Jay K. Rosengard , Richard H. Patten , Don E. Johnston Jr & Widjojo Koesoemo (2007) THE PROMISE AND THE PERIL OF MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS IN INDONESIA, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 43:1, 87-112, DOI:

10.1080/00074910701286404

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910701286404

Published online: 08 Nov 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 233

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/07/010087-26 © 2007 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910701286404

THE PROMISE AND THE PERIL OF

MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS IN INDONESIA

Jay K. Rosengard*

John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Richard H. Patten, Don E. Johnston, Jr and Widjojo Koesoemo* Independent Consultants, United States and Indonesia

After the 1997 East Asian crisis, central banks throughout the region tried to reduce the risk of future bank failures by promulgating regulatory reforms. The results in Indonesia have been to concentrate rather than mitigate banking risks, and to decrease the access of low-income households and enterprises to formal fi nancial

services, especially in rural areas. The most severe casualties of the ‘reforms’ have been local government-owned micro fi nance institutions. In the provinces where

these institutions have functioned best, they have addressed a market failure by ex-tending coverage to areas not served by conventional fi nancial institutions.

Under-standing the past performance and potential for replication of these success stories continues to be important because of the substantial gaps that remain in the access of rural Indonesian households and micro enterprises to fi nancial services.

INTRODUCTION: THE UNINTENDED

CONSEQUENCES OF REGULATORY REFORM

After the 1997 monetary and economic crisis in East Asia, central bankers through-out the region tried to reduce the risk of future bank failures by promulgating a series of regulatory reforms. The main assumptions behind the reforms were that bigger fi nancial institutions were safer than smaller ones, and that traditional

banking practices were less risky than non-conventional fi nancial services.

Indonesia was no exception to the trend of fi nancial sector re-regulation.

This meant that relatively small, community-based fi nancial institutions were

instructed to merge into larger, centralised entities, and that innovative

micro-fi nance services were viewed with suspicion and hostility.

* The research for this article was commissioned by the German aid agency GTZ GmbH. The authors thank Dr Alfred Hannig, Dr Dominique Gallman and Ibu Aimee Patalle for their kind support of this work; the managers and staff of the regional offi ces of Bank

Indo-nesia for their insights and for their assistance in arranging interviews with local fi nancial

institutions; and the management and staff of provincial development banks and

micro-fi nance institutions for their time and patience. Finally, the authors wish to express their

appreciation to the editor and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. We retain full responsibility for any remaining errors.

The results have been to concentrate rather than mitigate banking risks, and to decrease the access of low-income households and enterprises to formal fi nancial

services, especially in rural areas. Among the casualties of the regulatory reforms have been two broad categories of micro fi nance institutions, the fi rst owned by

local governments and operating at both the sub-district (kecamatan) and village (desa) levels, and the second owned by villages and operating at the village level only.1 The generic terms for these are, respectively, village credit institutions

(lem-baga dana kredit pedesaan, LDKPs) and village credit bodies (badan kredit desa, BKDs). But these institutions go by a variety of names in different parts of the archipel-ago, resulting in a bewildering array of acronyms (see appendix). To avoid confu-sion, in this paper for the most part we shall use the term ‘GMFIs’ to refer to local government-owned micro fi nance institutions operating at the sub-district and

village levels, and ‘VMFIs’ to refer to village-owned micro fi nance institutions.2

The unintended consequences of the reforms are especially important because, although Indonesia is recognised as a world leader in commercial micro fi nance,

it is also unique among developing countries in that its most successful

micro-fi nance institutions to date are public sector institutions such as the GMFIs and

VMFIs. In fact, the best-known micro fi nance provider in Indonesia is Bank Rakyat

Indonesia (BRI), a full-service commercial bank that was owned entirely by the central government until the end of 2003, and whose majority owner is still the state. But because BRI has been written about extensively elsewhere, it will not be reviewed here.3

The purpose of this article is to offer suggestions on how the lessons from past GMFI and VMFI accomplishments and failures can be utilised to guide current efforts to expand the coverage of formal fi nancial institutions, particularly in

provinces that do not yet have such institutions. In the provinces where they have functioned best, GMFIs and VMFIs have proven to be sustainable, and have made a signifi cant contribution to increasing the access of low-income households and

micro enterprises to micro fi nance, particularly in rural areas.

Understanding the past performance and potential for replication of GMFIs and VMFIs continues to be important because substantial gaps remain in the access of Indonesian households and micro enterprises to micro fi nance services—despite

the success of a number of such institutions to date and despite the strong desire of some senior policy makers to reduce the current degree of fi nancial exclusion.

Indeed, recent surveys indicate that nearly 50% of Indonesian households con-tinue to lack effective access to micro credit, while the proportion of rural house-holds who actively use savings accounts is still below 40%.4

We begin our examination of the relevance, effectiveness and potential of the GMFI/VMFI approach by reviewing the origins and development of these

insti-1 The new regulations also failed to address critical ambiguities and uncertainties in ear-lier legislation, further constraining the strategic and operational options of these local government-owned micro fi nance institutions.

2 See Holloh (2001) for a survey of micro fi nance institutions in Indonesia.

3 For further information on BRI and its village units, see Patten and Rosengard (1991: ch. 5) and Patten, Rosengard and Johnston (2001).

4 See, for example, BRI Survey Team and CBG Advisors (2001: section IV).

tutions. We then assess their potential contribution and identify the key factors determining their performance. These fi ndings are used to develop

recommenda-tions for the development of GMFIs and VMFIs, with special attention given to provinces that do not yet have such institutions.

DEVELOPMENT OF VILLAGE-ORIENTED MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS

The development of institutions delivering banking services at the village level can best be understood if looked at in three phases: development to the late 1970s; development during the 1980s and up to the passage of the Banking Law of 1992; and development (and deterioration) from 1992 to the present.

Development until the late 1970s

Indonesia’s original micro fi nance institutions, the VMFIs, began life in the 1890s as

bank desa (village banks) and lumbung desa (paddy banks, or facilities to store rice rather than cash). They were fi rst set up in Java and Madura during the Dutch

colo-nial period as community organisations, and were supervised by BRI. Although they proved to be highly durable, most notably by surviving the Great Depression in good condition, nevertheless two major economic dislocations—the Japanese occupation during World War II and hyperinfl ation during the mid-1960s—

resulted in the need for some to be revived with loan capital from BRI.

In the early 1970s the governor of Central Java set up a new type of organisation, the sub-district credit body (badan kredit kecamatan, BKK), to provide micro fi nance

in villages where VMFIs had ceased to operate. Each BKK was headquartered in the sub-district, with the sub-district head assigned responsibility for oversight. These institutions reached borrowers in the villages by sending a motorcycle team to each village once a week, or on market day in the fi ve-day market cycle based

on the Javanese calendar. They relied on the recommendation of the village head, who affi rmed that the loan applicant was a village resident, had an enterprise

as stated and was fi nancially reliable; their credit terms were modelled on those

of the VMFIs. Each BKK received a loan of Rp 1 million as start-up capital, to be repaid in three years. By 1977–78 they had learned how to make loans at the vil-lage level, but in the process many of them had lost much of their original capital and were not operating on a sustainable basis.5

Development until the passage of the Banking Law of 1992

The VMFIs experienced no signifi cant change in their operations during the 1980s.

They continued to make very small loans at the village level for petty trading, agriculture and handicraft enterprises. In 1988, at the initiative of BRI, the super-vision of market banks and other local banks that could potentially compete with BRI village units (the micro fi nance offi ces of BRI) was transferred to the central

bank, Bank Indonesia (BI), to avoid any confl ict of interest. Unfortunately, BI

mis-understood the nature of the VMFIs and took over direct supervision of them as well. This was quite unnecessary: there was virtually no overlap between VMFIs

5 For more on the origins and evolution of the BKKs, see Patten and Rosengard (1991: ch. 4).

and BRI village units in the markets they served, so the potential for confl ict of

interest was negligible.6 When it became clear that BI could not directly supervise

the more than 5,000 VMFIs, it instructed BRI to again supervise them on its behalf. Beginning in the mid-1990s, BI paid part of the costs of such supervision; before that, the VMFIs had covered all of these costs.

In 1978–79, the central government, with assistance from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), launched the Provincial Area Development Program with the objective of testing ideas on how government might reach the poor and assist them to improve their income-earning capacity. The program was managed by a team from the Ministry of Home Affairs, the National Development Planning Agency, the Ministry of Finance and BRI, and operated in selected districts7 in six provinces: West Sumatra, West Java, East Java,

South Kalimantan, West Nusa Tenggara and (later) Bali. Local governments pro-posed projects to the provincial development planning agencies, where they were cleared with the appropriate technical agency. A large percentage of the projects proposed were for the provision of loans.

The Provincial Area Development Program tested 39 different methods of deliv-ering loans at the local level, including through technical agencies, cooperatives and special groups organised to rotate credit among their members. Although expansion of the existing VMFI system to additional villages was not tested, of all the credit delivery systems that were trialled, the only one found capable of deliv-ering credit at the village level on a sustainable basis was that of a sub-district-level credit institution serving its constituent villages through motorcycle teams operating village posts. These institutions needed to be supervised, trained, sup-ported with simple asset and liability management facilities, and inspected by a commercial bank such as a provincial development bank.8 At the start of the

program, additional capital was injected into the BKKs in fi ve pilot districts in

Central Java. These institutions immediately expanded, began to make a profi t

and became fully sustainable. This encouraged a similar injection of capital into the remaining BKKs outside the pilot districts, with the same result.

In the early 1980s, the basic idea of a lending organisation located in the sub-district, and sending motorcycle teams to villages to deliver credit services, was expanded to test districts in other provinces participating in the Provincial Area Development Program. These bodies included the credit institutions for small-scale activities (lembaga kredit usaha rakyat kecil, LKURKs) in East Java, the rural credit institutions (lembaga kredit pedesaan, LKPs) in West Nusa Tenggara, and the BKKs and small enterprise fi nancing institutions (lembaga pembiayaan usaha kecil,

LPUKs) in South Kalimantan. They were successful in delivering credit at the

vil-6 Despite their name, BRI village units actually operate at the sub-district level, so do not compete with the VMFIs. In contrast, the market banks operate at the sub-district or district level, thus potentially competing with BRI branches and village units.

7 For brevity, in this paper the term ‘district’ should be taken to include kabupaten (dis-tricts) and kota (municipalities). Both are Level II governments directly under the Level I provinces.

8 Each province had one provincial development bank (bank pembangunan daerah, BPD), jointly owned by the provincial and district governments.

lage level on a sustainable basis, and later became known collectively as LDKPs— or GMFIs as we refer to them here.

It soon became apparent that supervision by a provincial development bank was crucial to the success of these GMFIs; they succeeded best where there was an authorised and competent provincial development bank to supervise them. The system was less successful in delivering credit to villages on a sustainable basis in places like West Java, where the local government decided to set up its own supervision system and use the provincial bank only to monitor fi nancial reports.

In West Sumatra, the local GMFIs, known as pitih paddy banks (lumbung pitih nagari, LPNs), were located in the pitih, a traditional level of local government that was no longer active. The Provincial Area Development Program encouraged the provincial government to give responsibility for supervision and support services to the West Sumatra provincial development bank, but by the time this actually occurred, many of these institutions were barely operational.

In the mid-1980s, the USAID-funded Financial Institutions Development project expanded the development of fi nancial institutions to additional districts in the

provinces covered by the Provincial Area Development Program (West Sumatra, West Java, East Java, South Kalimantan and West Nusa Tenggara). In the second phase of this project in the latter part of the decade, Bali was added to these prov-inces. In Bali, the operations of the village credit institutions (lembaga perkreditan desa, LPDs) were headquartered in the village, not the sub-district, so there was no need for mobile teams to travel to the villages. The villages in question were Bali’s traditional villages (desa adat) rather than the offi cial villages (desa dinas) of

the formal government organisation, and therefore gained strength from being tied into the island’s cultural traditions.

Development (and deterioration) from 1992 to the present

The GMFIs, along with the VMFIs, village banks and other institutions delivering micro enterprise credit at the village level, were recognised in article 58 of the 1992 Banking Law.9 The law’s implementing regulation again recognised these

exist-ing community and village-level fi nancial institutions,10 but it also lumped them

together with all other people’s credit banks (bank perkreditan rakyat, BPRs—essen-tially, community banks), set a minimum capital requirement of Rp 50 million and gave them fi ve years to become fully licensed as BPRs. At the time, Rp 50 million

was far more than the capital required by a village-level credit institution. It was possible that the best of the GMFIs organised at the sub-district level, including many BKKs in Central Java, would be able to achieve this requirement within the fi ve-year period. However, the implementing regulation did not clarify what

would happen to institutions that did not become BPRs within this period. Since that time, further large increases in the minimum capital requirement have only strengthened the initial impact. The 1992 Banking Law became one of the two defi ning events of the decade for VMFIs and GMFIs, the other being the Indo nesian

monetary and economic crisis beginning in 1997. As micro fi nance institutions, the

VMFIs and GMFIs turned out to be in a far better position to deal with the mon-etary and economic crisis than with the effects of inappropriate regulation.

9 Law 7/1992 on Banking (see McLeod 1992).

10 Government Regulation 71/1992 on People’s Credit Banks.

CURRENT STATUS OF VILLAGE-ORIENTED MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS

BKDs in Java and Madura

The fi rst village credit bodies (badan kredit desa, BKDs) were established in the

1890s during the Dutch colonial period.11 At the end of May 2003, Java and

Madura had 4,518 active and 827 non-active BKDs. The active BKDs had a total of Rp 186.8 billion of loans outstanding to 438,938 borrowers—implying an average loan size of Rp 426,000 (about $51). Their combined equity (including retained profi ts) totalled Rp 222.5 billion, resulting in a combined, system-wide capital

adequacy ratio (CAR) of more than 100%. One of the results of this high CAR is that most BKDs do not need to mobilise savings to have suffi cient loanable funds

to meet village loan demand. Nevertheless they had 524,671 savers with Rp 35.3 billion in their savings instrument, Tabungan BKD.

The elected village head is ex offi cio principal commissioner of the BKD, and chooses two other commissioners. The accounts are discussed at least once a year at a general meeting of the members of the village. Most BKDs are open only once a week, on market days. A book-keeper serves four or fi ve BKDs, and is trained

and paid by BRI with funds the BKDs themselves provide on the basis of their loan portfolio size.

The BKDs are reasonably successful at delivering micro enterprise loans at the village level. Their interest rates are almost double those of the BRI village units, but the loans involve much lower transaction costs for the borrower. They typi-cally go to very small enterprises operating almost entirely within the village, and owned mainly by women. If borrowers in outlying villages had to travel to sub-district headquarters to arrange and service their loans, they would fi nd their

transaction costs much higher than the interest they actually pay.

The BKDs also provide savings services, but savers are able to make withdraw-als only on the days they are open. This is not completely satisfactory, since a major reason for saving by low-income people is to meet family emergencies, which cannot be programmed for a certain day of the week. But most BKDs have little incentive to provide savings services, since additional funds are surplus to lending requirements; the savings they collect are therefore simply deposited in an interest-bearing account at BRI. Savings deposits in the BKDs are not insured, though with their large equity the chances of loss through collapse of the institu-tion are small.

BKDs are supervised by BRI branch staff ‘on behalf of BI’, which pays part of the supervision costs. The BRI supervisor goes through the books of each BKD at least once a month and checks on borrowers who have defaulted on their loans. Any problems found are reported to the district government, which is charged with ordering the action necessary to correct them. Asset and liability manage-ment is very simple. If there is a surplus of liquidity, it is deposited in a BRI branch or village unit; if there is a shortage of loanable funds, as might happen in a rela-tively new BKD, the BKD may be able to borrow from BRI.

In the past there has been some misunderstanding about the fi nancial

condi-tion of the BKDs’ credit portfolios. Because the procedures for writing off bad loans were complicated, BKDs simply left bad loans in their portfolios, infl ating

11 For further information on the BKDs, see BRI International Visitors Program (1998).

the nominal level of loans outstanding, and displaying misleadingly high levels of bad debt to the casual observer. In addition, they often did not fully reserve against the bad debt in their portfolios, leading to some over-statement of profi ts

and equity. Under instruction from BRI, the balance sheets have recently been cleaned up. Once the backlog of bad debt had been written off, BRI instructed the BKDs to establish a routine, formula-based system of reserving for bad debt; they were also instructed to automatically write off unrecoverable loans (which were to be 100% reserved against) by moving them from the balance sheet to an off-balance ‘black list’ after a certain period. BRI also instructed its local branch man-agers and BKD supervisors to work with local governments to develop action plans for the 800-odd inactive BKDs, many of which were insolvent.

To support BKDs that have not built up enough capital to fully meet loan demand in the villages they serve, BRI has asked BI for permission to lend to them.12 BRI’s compliance division considers special permission to be necessary

because of continuing uncertainty over the legal status of BKDs. Along with the GMFIs, they were specifi cally recognised in the Banking Law of 1992. However,

subsequent decrees under this law did not differentiate between their capital requirements and those of privately owned BPRs, even though the capital require-ments of a BPR are far greater than those of an institution serving a single village. Legal uncertainty also extends to the BKDs’ status as deposit-taking institutions, largely preventing their spread to new areas since 1992. Because deposit taking has typically not been a core activity for them, it should be possible to develop a way around this legal obstacle without waiting for a new law on micro fi nance

institutions; one possibility would be for them to act as savings agents on behalf of a commercial bank such as BRI.

BKKs in Central Java

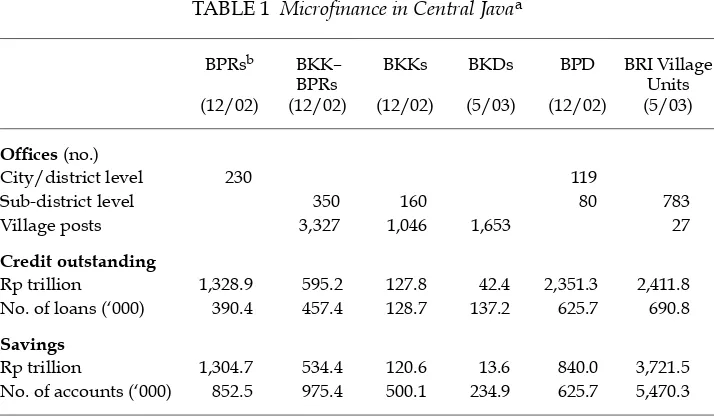

Over the past decade the sub-district credit bodies (badan kredit kecamatan, BKKs) in Central Java have employed a number of strategies with respect to the 1992 Banking Law. As of 31 December 2002, 350 of them had succeeded in achieving the status of BPRs (or BKK–BPRs, as we call them here), while 160 continued to operate as before (table 1).13

Two important trends can be observed for BKKs that have succeeded in becom-ing BPRs or are attemptbecom-ing to do so. First, durbecom-ing the process of becombecom-ing BPRs, many BKKs consolidated their operations at the sub-district level and eliminated the motorcycle teams that had previously provided credit at the village level. Thus, the period since 1992 has seen a withdrawal rather than an expansion of banking services in the villages. This tends not to show up in the statistics on the number of village posts; instead, the level of service to the village simply drops from weekly to monthly or less.

Second, at least since the crisis of 1997–98, payroll deduction lending to salaried workers has been heavily emphasised. Such loans have become a much larger

12 At the time of writing, BI was still considering this request.

13 BI data do not differentiate local government-owned (perusahaan daerah, PD) BKK–BPRs from the more numerous privately owned (perseroan terbatas, PT) BPRs. However, the au-thors were able to obtain detailed data on both BKK–BPRs and BKKs from the Central Java provincial development bank.

part of these institutions’ loan portfolios, while the percentage of the portfolios comprising loans to micro enterprises has declined accordingly. This same trend is apparent in the portfolios of BRI village units and provincial development banks, as well as those of the former GMFIs in other provinces.

The operations of Central Java’s BKK–BPRs have been adversely affected by BI regulations, which have diminished the role of the provincial development bank in providing asset and liability management services. Connected-party exposure limits are being applied to the deposits of local government-owned BPRs with the provincial development bank, and to the latter’s loans to the former, because the ownership of both types of institution is considered to be the same. In practice, this means that a BPR must go to at least one other bank, other than the provincial development bank and other Central Java BPRs, to place its excess liquidity if this is more than 10% of its equity. Previously such deposits were a valuable source of liquidity for the provincial development bank, which used part of the earnings on these funds to help pay the cost of BKK supervision and training. With the BKKs now forced to spread their deposits to other banks, the provincial development bank is fi nding it less attractive to support local government-owned BPRs.

Ulti-mately, this means that the bank is unwilling to supervise BKK–BPRs as carefully as before. Application of the connected-party rules in this way makes BKK–BPRs riskier, not less risky. The regulation that the provincial development bank is not permitted to lend an amount more than 10% of its capital to the BPRs has not yet restricted such lending, but it may in the future. For this calculation, all the local government-owned BPRs are lumped together as if they were a single bank, because their ownership is considered to be the same.

TABLE 1 Microfi nance in Central Javaa

BPRsb BKK– BPRs

BKKs BKDs BPD BRI Village Units (12/02) (12/02) (12/02) (5/03) (12/02) (5/03)

Offi ces (no.)

City/district level 230 119

Sub-district level 350 160 80 783

Village posts 3,327 1,046 1,653 27

Credit outstanding

Rp trillion 1,328.9 595.2 127.8 42.4 2,351.3 2,411.8 No. of loans (‘000) 390.4 457.4 128.7 137.2 625.7 690.8

Savings

Rp trillion 1,304.7 534.4 120.6 13.6 840.0 3,721.5

No. of accounts (‘000) 852.5 975.4 500.1 234.9 625.7 5,470.3

a Central Java had 29 districts, six municipalities, 534 sub-districts and 8,543 villages in

2003. Its population was 31.8 million (8.24 million households) in 2002. See appendix for an explanation of the various types of fi nancial institutions.

b Excluding BKK–BPRs.

Sources: Bank Indonesia; Bank Jateng; Bank Rakyat Indonesia; Badan Pusat Statistik.

One result of the movement to transform BKKs into BPRs appears to be a signif-icant increase in competition at the sub-district level for micro credit and savings customers. Although BKKs (like other GMFIs) tend to make somewhat smaller loans on average through their sub-district offi ces than BRI village units, there is

considerable overlap in the market segment served. Such competition is certainly benefi cial to borrowers and savers in the areas surrounding the sub-district

cen-tre. It is unfortunate, however, that this has been accompanied by a withdrawal of services from relatively distant villages.

The overall status of micro fi nance activity in Central Java is shown in table 1.

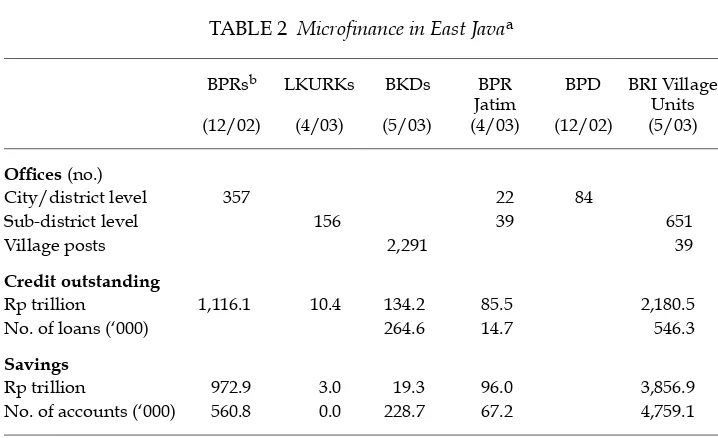

LKURKs in East Java

In East Java, the change in status of the credit institutions for small-scale activities (lembaga kredit usaha rakyat kecil, LKURKs) established in the early 1980s has gone through two stages. First, many of the more successful ones were able to meet BI’s criteria and become BPRs. Next, in 2001, 62 of these BPRs were consolidated into a single institution, BPR Jatim, with one head offi ce, 21 branches and 39 cash posts

(table 2). The main reason cited for this consolidation was to eliminate the large number of commissioners and directors required by BI regulation for each BPR; it would also allow the movement of personnel from branch to branch as needed and facilitate the setting up of regular staff training courses. It was hoped that the consolidation would protect BPR Jatim from government interference in the selec-tion of staff, allowing it to base its choice on educaselec-tion, mathematical competence and other objective criteria.

TABLE 2 Microfi nance in East Javaa

BPRsb LKURKs BKDs BPR Jatim

BPD BRI Village Units (12/02) (4/03) (5/03) (4/03) (12/02) (5/03)

Offi ces (no.)

City/district level 357 22 84

Sub-district level 156 39 651

Village posts 2,291 39

Credit outstanding

Rp trillion 1,116.1 10.4 134.2 85.5 2,180.5

No. of loans (‘000) 264.6 14.7 546.3

Savings

Rp trillion 972.9 3.0 19.3 96.0 3,856.9

No. of accounts (‘000) 560.8 0.0 228.7 67.2 4,759.1

a East Java had 29 districts, nine municipalities, 624 sub-districts and 8,457 villages in 2003.

Its population was 35.2 million (9.87 million households) in 2002. See appendix for an explanation of the various types of fi nancial institutions.

b Excluding BPR Jatim.

Sources: Bank Indonesia; BPR Jatim; Bank Jatim; Bank Rakyat Indonesia; Badan Pusat Statistik.

The consolidation into one institution has simplifi ed the audit task of BI,

which does not have the capacity to audit a large number of small BPRs. Even if undertaken annually, a BI audit would not be an adequate substitute for the close supervision previously provided by the provincial development bank. It had one supervisor in each of its branches, thus allowing the semi-monthly or monthly checking that has been found necessary to keep micro fi nance institutions healthy.

Supervision of the remaining 156 LKURKs that were not consolidated into BPR Jatim has been moved from the provincial development bank to BPR Jatim. It is expected that in time many of these will become offi ces of BPR Jatim rather than

remain separate BPRs.

The same trends as were apparent in the development of BKKs in Central Java are also found in East Java. There has been consolidation of credit and savings operations at the sub-district level and withdrawal of the motorcycle teams that formerly delivered credit services to more distant villages. (This occurred at the time of conversion to BPR status, not at the time of consolidation of the 62 BPRs into a single BPR Jatim.) There has also been the same movement towards lending to salaried employees who agree to repay their loans through automatic payroll deductions.

The overall status of micro fi nance activity in East Java is shown in table 2.

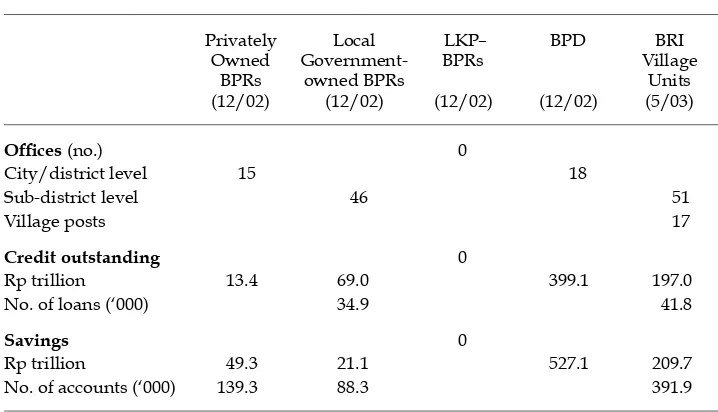

LKPs in West Nusa Tenggara

The situation in West Nusa Tenggara (Nusa Tenggara Barat, NTB) is similar to that in East Java. The province’s rural credit institutions (lembaga kredit pedesaan, LKPs) were set up on the same general lines as the LKURKs, with a staff of three or four and direct supervision and support from the provincial development bank, each branch of which had at least one offi cer whose job it was to visit all

LKPs on a regular basis—at least once a month. After the BI regulations for BPRs under the 1992 Banking Law became known, the provincial government decided to convert all LKPs to BPRs (here called LKP–BPRs), although in some cases small or problem institutions were fi rst merged into neighbouring LKPs. As a result, all

sub-districts in West Nusa Tenggara continue to be served by an LKP–BPR, some serving more than one sub-district (table 3).

In the conversion to BPRs, the close supervisory role of the provincial develop-ment bank was lost. Instead, BI attempted to supervise each BPR directly, but it simply did not have enough staff to do so; the head of one BPR told us that his institution had been audited only twice in the fi ve years since its establishment. A

second important problem is lack of control by BPR management and supervisory boards over the hiring of staff. Each staff appointment is made by the provin-cial government as if it were an appointment to the provinprovin-cial bureaucracy. As a result, insuffi cient consideration is given to candidates’ specifi c qualifi cations for

bank employment.

At the time of writing, the provincial government was seriously considering whether to consolidate the LKP–BPRs into a single BPR for the whole of the prov-ince, as was done in East Java. However, there appeared to be a difference of opinion between the provincial and district governments, with the latter gener-ally favouring more limited consolidation of all sub-district-level LKP–BPRs into district-level BPRs with sub-district-level branches. The core of the disagreement

had little to do with effi cient operations or optimal coverage; rather, it was about

the allocation of dividends from the profi ts of the BPRs.

Since the implementation of regional autonomy in 2001 and the handing of new responsibilities to the districts and provinces, most local governments have perceived themselves to be short of funds. District governments are particularly eager to acquire or establish sustainable, wholly owned fi nancial institutions of

their own in the hope of realising a steady dividend stream (although consid-erations of prestige and patronage also play a role). Consolidation into a single LKP–BPR at the provincial level would probably involve the provincial govern-ment taking a signifi cant share of ownership, without paying full compensation

to the current local government owners of the merging institutions for the dilu-tion of their equity. The latter would then receive a correspondingly smaller share of the profi ts contributed to the new institution by the LKP–BPRs in their district.

As noted above, under the present set-up with individual BPRs, district govern-ments have relatively little infl uence over staffi ng and operations. Whether

con-solidation into district-level BPRs would mean more government interference in staffi ng and operations would depend on whether the supervisory boards of the

BPRs were given full control over such matters.

Not only has fi nancial pressure proven to be one source of disagreement between

the provincial and district governments, but pressure to increase dividends rap-idly has resulted in a repeat of the same trends observed in Central and East Java: consolidation of operations at the sub-district level; abandonment of lending services at the village level by eliminating motorcycle teams; and concentration

TABLE 3 Microfi nance in West Nusa Tenggaraa

Privately Owned

BPRs

Local

Government-owned BPRs

LKP– BPRs

BPD BRI

Village Units (12/02) (12/02) (12/02) (12/02) (5/03)

Offi ces (no.) 0

City/district level 15 18

Sub-district level 46 51

Village posts 17

Credit outstanding 0

Rp trillion 13.4 69.0 399.1 197.0

No. of loans (‘000) 34.9 41.8

Savings 0

Rp trillion 49.3 21.1 527.1 209.7

No. of accounts (‘000) 139.3 88.3 391.9

a West Nusa Tenggara had six districts, two municipalities, 62 sub-districts and 703

vil-lages in 2003. Its population was 4.2 million (1.1 million households) in 2002. See appendix for an explanation of the various types of fi nancial institutions.

Sources: Bank Indonesia; BPD NTB; Bank Rakyat Indonesia; Badan Pusat Statistik.

on loans to salaried employees. Although in most cases village service appears to have been profi table, regulatory pressures, combined with staff shortages, effi

-ciency concerns and pursuit of short-term profi ts in faster-growing urban

mar-kets, have consistently led to withdrawal of services at the village level.

The overall status of micro fi nance activity in West Nusa Tenggara is shown in

table 3.

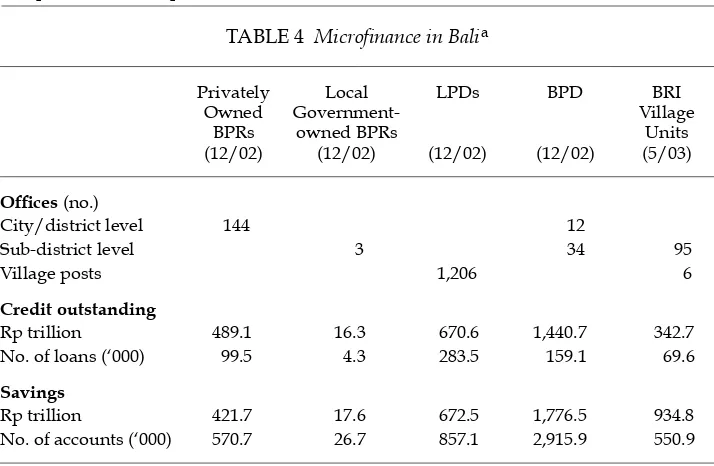

LPDs in Bali

In terms of effective access to and utilisation of micro fi nance services, the island

province of Bali has achieved far more than any other area in Indonesia. With nearly as many micro fi nance loans as households, no other province approaches

Bali’s ratio of micro fi nance loans to total households. The phrase ‘Bali is

differ-ent’ was a recurring one during the authors’ fi eld visits to Bali. The success of

micro fi nance in Bali is not due to a single institution. Rather, it is the result of

several micro fi nance institutions all showing strong outreach performance. While

the BRI village units reach about the same proportion of households as elsewhere, Bali’s privately owned BPRs are unusually active, and appear to be reaching more borrowers in total. Indeed, Bali is in the unusual position of having more BPRs than BRI village units (table 4).14 In addition, some privately owned commercial

banks, the best known of which is Bank Dagang Bali, are active in commercial micro fi nance. While the provincial development bank makes most of its loans to

employees rather than enterprises, its wide outreach to private sector workers makes it another important source of micro-scale fi nance to households.

However, the greatest difference in micro fi nance access between Bali and other

provinces is due to its village credit institutions (lembaga perkreditan desa, LPDs). They are an integral part of the desa adat (traditional village), as distinct from the desa dinas (offi cial village)—the smallest unit of local government

through-out Indonesia. On average, there are more than two desa adat for each desa dinas, but this ratio can vary widely from area to area, and the borders of the two vil-lage types frequently cut across each other. Desa adat are highly participatory and accountable local religious–social institutions. Bali’s generally vibrant and micro-enterprise-friendly economy, the strong bond of ethnic Balinese to the desa adat, and scrupulous traditional attitudes towards fulfi lling debt obligations and the

attendant maintenance of social standing, combine to create an environment that is very nearly ideal for the success of the LPDs.

While some LPDs are quite large, with total assets in the tens of billions of rupiah, in general they have consistently and successfully resisted changing their status to become BPRs. According to the managers and supervisors we inter-viewed, their governance and focus on serving the (Balinese) residents or mem-bers of a particular desa adat do not match well with the structure and regulations of BPRs. At least one desa adat, Sanur, owns a BPR in addition to its LPD, but the purpose of the two institutions is quite different: while the BPR is considered a purely commercial enterprise, the LPD is intended to ensure that all residents have access to basic fi nancial services.

Local government is supportive of the LPDs, and desa dinas appreciate the con-tribution of desa adat to the infrastructure and development budgets of the villages.

14 See Winship (2003) for a more in-depth look at the BPR sector in Bali.

At the provincial level, the governor was active in advocating to BI that the LPDs be allowed to maintain their special non-bank status while continuing to mobilise savings from within the village. At present BI is quite supportive of them. The current BI branch manager pointed out to us that the central bank already has a big job supervising more than 140 BPRs; attempting to supervise more than 1,200 LPDs as well would be impossible.

Each LPD is staffed by a minimum of three persons—a manager, a teller and a book-keeper—all from the desa adat. Most are open fi ve or six days per week, and

most employ staff on a full-time basis, even during the start-up phase. This entails a certain amount of sacrifi ce on the part of staff in a new LPD, who are not well

compensated for the hours worked, but also provides a strong incentive to build up the business. Because each LPD is a stand-alone institution, its managers have no real career path, except to develop their own LPD. To provide an indicator of the ability of managers as well as a degree of job status, a training certifi cation

system has been developed.

Within the desa adat, each LPD is supervised by a supervisory committee, which receives an honorarium. Typically, the desa adat appoints more members to the supervisory board than are required by regulation, in order to allow wider accountability and daily supervision. In such cases, the honorarium for super-visory board members is also divided. External supervision has been relatively weak, though the underlying strength of most LPDs at the local level has generally prevented signifi cant problems from developing. Recently, the provincial

govern-ment has taken steps to modify the system of supervision substantially. Under the new system, the provincial development bank will be responsible for fi nancial

TABLE 4 Microfi nance in Balia

Privately Owned

BPRs

Local

Government-owned BPRs

LPDs BPD BRI

Village Units (12/02) (12/02) (12/02) (12/02) (5/03)

Offi ces (no.)

City/district level 144 12

Sub-district level 3 34 95

Village posts 1,206 6

Credit outstanding

Rp trillion 489.1 16.3 670.6 1,440.7 342.7

No. of loans (‘000) 99.5 4.3 283.5 159.1 69.6

Savings

Rp trillion 421.7 17.6 672.5 1,776.5 934.8

No. of accounts (‘000) 570.7 26.7 857.1 2,915.9 550.9

a Bali had eight districts, one municipality, 53 sub-districts, 678 desa dinas and 1,406 desa adat in 2003. Its population was 3.2 million (848,000 households) in 2002. See appendix for an explanation of the various types of fi nancial institutions.

Sources: Bank Indonesia; Bank BPD Bali; Bank Rakyat Indonesia; Badan Pusat Statistik.

supervision (essentially, audit and monitoring of regular fi nancial reports), while

a newly formed, district-level supervisory body will oversee training and opera-tional supervision. Financing to cover the cost of this new body is intended to be generated by the LPD system itself, though the implementation of this is still evolving. Up to the present, much of the development of the LPD system has been externally facilitated, with signifi cant policy and training inputs from the

Promo-tion of Small Financial InstituPromo-tions project of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). With the new approach to supervision, however, most training and much of the institutional development of LPDs will be shouldered by the new supervisory structure.

In addition to its role as fi nancial supervisor, the provincial development bank

fulfi ls a number of other functions for the LPDs: management of excess

liquid-ity; providing a line of credit; monitoring and reporting; and playing a key role in institutional development. According to supervisors from both the provincial bank and the new district-level supervisory body, the provincial government currently has plans to establish LPDs in all the desa adat that do not yet have one—over 200 in all. This will probably create a need for a workable ‘part-time’ operating model along the lines of the BKDs, as many of the remaining desa adat are unlikely to be able to support a full-time LPD.

Uniquely among Indonesia’s VMFIs, Bali’s LPDs were able to retain their status and prosper throughout the 1990s, when regulatory issues created serious opera-tional diffi culties for VMFIs in every other province. A strong sense of local

own-ership, support from local and provincial governments, consistent support from the provincial development bank, timely realisation by BI of the benefi ts of the

system, and capable technical assistance and institutional development played mutually reinforcing roles in preserving the character and mission of the LPDs. As a result, of all the VFMI systems in use across Indonesia, the LPD system has come closest to achieving the goal of providing universal access to micro fi nance

services. While not all aspects of the LPD experience—particularly Balinese atti-tudes towards debt and the cohesiveness of the desa adat—can be replicated else-where, the ‘win–win’ institutional relationships developed in Bali could serve as a model for any province.

The overall status of micro fi nance activity in Bali is shown in table 4.

BKKs and LPUKs in South Kalimantan

In contrast to the happy outcome in Bali, the story of the sub-district credit bod-ies (badan kredit kecamatan, BKKs) of South Kalimantan is largely one of missed opportunities and unrealised potential. Established under a governor’s decree in 1985 (EKU 09/1985), they were intended to fi nance micro- and small-scale

enter-prises, mainly in rural areas. Over time the provincial government established 34 BKKs, which were initially permitted to mobilise savings. This changed following the enactment of the 1992 Banking Law, when the provincial government decided to follow the new law literally and immediately. Apparently overlooking both article 58 of the law, which formally recognised GMFI operations such as those of the BKKs, and the implementing regulation providing for a fi ve-year transition

period, the provincial government prohibited BKKs from accepting savings, to take effect immediately. For most BKKs, this left only their initial capital for use as loanable funds.

Despite this, the provincial government went on to establish, through another’s governor’s decree (316/1993), 75 small enterprise fi nancing institutions (lembaga

pembiayaan usaha kecil, LPUKs) in the remaining sub-districts that did not have a BKK, plus one special unit in the governor’s offi ce (table 5). These provide credit

to micro enterprises but do not collect savings. At the same time, some BKKs (20 at the time of writing) have changed their status to become BPRs, because they have grown enough to fulfi l the minimum capital requirement for doing so. Of these,

15 are considered sound by BI.

The staff of most BKKs and LPUKs consist of a manager, cashier, book-keeper and credit offi cer. The manager is responsible to the sub-district head for the

per-formance of the BKK/LPUK. The sub-district head is an employee of the district government and reports directly to the district head. The minimum staffi ng of a

BKK or LPUK is two persons. This is considered risky by supervisors owing to the lack of separation of jobs, but is nevertheless implemented in some of the smallest BKKs and LPUKs for reasons of effi ciency. The local government-owned BPRs,

on the other hand, carry the full staffi ng structure required of BPRs: a board of

supervisors, board of directors, internal controller, funds manager, loan manager, cashier and book-keeper.

The capital of the BKKs/LPUKs originates from provincial government equity participation of Rp 10 million in each institution. Some of the funds (Rp 500,000) are used for basic fi nancial institution training and the remainder for fi nancing

operations. In some districts the district government has also made an equity con-tribution. Several district governments have expressed a preference to establish

TABLE 5 Microfi nance in South Kalimantana

Privately Owned

BPRs

Local

Government-owned BPRs

BKKs LPUKs BRI

Village Units

(6/03) (6/03) (6/03) (6/03) (6/03)

Offi ces (no.)

Headquarters & other 6 1

Sub-district level 20 14 75 72

Village posts 3

Credit outstanding

Rp trillion 26.2 12.1 1.2 4.2 162.5

No. of loans (‘000) 2.9 8.1 6.3 12.7 36.6

Savings

Rp trillion 20.3 7.2 479.6

No. of accounts (‘000) 9.5 23.2 505.7

a South Kalimantan had nine districts, two municipalities, 119 sub-districts and 1,946

villages in 2002. Its population was 3.1 million (830,000 households) in 2002. See appendix for an explanation of the various types of fi nancial institutions.

Sources: Bank Indonesia; BPD Kalimantan Selatan; Bank Rakyat Indonesia; Badan Pusat Statistik.

new BPRs fully owned by them, rather than share ownership with the provincial government. Existing ownership is distributed between the provincial govern-ment, district governments and the provincial development bank. For example, 77% of PD BPR Martapura is owned by the province, 20% by the district of Banjar and 3% by the provincial development bank.

Changing the status of BKKs and LPUKs has a number of disadvantages, according to the head of the provincial economic infrastructure department. First, a BPR is required to follow all banking regulations, which complicates procedures and adds substantially to the administrative burden. Second, BPR status requires that the institution pay company income tax and withholding tax on the interest earnings of customers; BKKs and LPUKs are not liable for these taxes. Finally, becoming a BPR inevitably means that the institution must increase its capital sig-nifi cantly—not an easy task when the provincial government budget is limited.

As they attempt to extend their outreach throughout the sub-districts, the BKKs and LPUKs face serious limitations in relation to capital, human resources and infrastructure. With its initial capital alone, a BKK or LPUK may reach only 20 borrowers if the average loan amount is Rp 500,000. Given that each sub-district has on average approximately 7,000 households, they clearly need additional funding if they want to reach a signifi cant proportion of potential borrowers. One

option is savings mobilisation from sub-district residents, but this would appear to require a new law permitting micro fi nance institutions to mobilise savings

from the people.

Besides capital, these institutions face human resource constraints. Even though staff have been trained by BI, the provincial development bank and other institu-tions, supervisors feel that this has had little effect on their competence, profes-sionalism or motivation; most cite low salaries as the underlying cause of this poor outcome. Distance and inadequate road infrastructure, lack of vehicles and inconvenient offi ce locations also limit the business potential of BKKs and LPUKs.

Most are located in the back of sub-district government offi ce complexes, making

it diffi cult for customers to fi nd them.

Supervision was formerly carried out by a supervisory body consisting of members of the provincial development planning agency, the provincial eco-nomic bureau and the provincial development bank, although in practice the latter played the main role in supervision. The provincial development bank developed operational guidelines, conducted staff training, selected candidates in the recruitment process and supplied trained supervisors to conduct site visits for purposes of fi nancial control. However, the issuing of new BI regulations on

connected-party lending and cross-ownership were interpreted to mean that the bank should not be allowed to remain deeply involved in direct fi nancial (often

called ‘technical’) supervision, even for the non-bank BKKs and LPUKs. Its role was therefore reduced to providing ‘consultancy services’, while supervision became the responsibility of the economic bureau. This change affected the qual-ity not only of supervision but of reporting as well. In the past, these institutions regularly sent their fi nancial reports to the provincial development bank, which

prepared a consolidated report, with analysis, to present to the government. At present, accurate consolidated fi gures are no longer easily obtainable.

The overall status of micro fi nance activity in South Kalimantan is shown in

table 5.

REBIRTH OF VILLAGE-ORIENTED MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS Three approaches to serving rural communities

To make sense of the GMFI/VMFI experience, this section divides the institu-tions featured in this paper into three distinct groups: sub-district-level GMFIs; BPRs owned by local government; and village-owned fi nancial institutions. Each

of these major types is subject to variation, as detailed below.

Sub-district-level GMFIs

The GMFIs set up by provincial governments between 1978 and the late 1980s were modelled on the BKKs of Central Java, which had been set up in the early 1970s. Under this ‘classic’ model, the micro fi nance institution provided credit and

savings services to villages by dispatching teams from a sub-district-level offi ce.

In the villages these teams were assisted by the village head or other village elders in evaluating loan applicants and collecting loans that had fallen into arrears. The sub-district head was the offi cial head of each GMFI, supervising a minimum

staff of three. Staff were paid a profi t bonus, which in many cases amounted to

much more than their regular salaries. Most GMFIs broke even within a reason-ably short period of time.

The GMFIs were supervised and supported by the provincial development banks. One supervisor from each district-level branch of the bank supervised the GMFIs within the district, visiting them at least once a month to go through the books and review action taken, or to be taken, on loans in arrears. Problems were reported to the sub-district head or, in the rare cases in which the sub-district head was unable to correct the situation, to the district head. The head offi ce of

each provincial development bank maintained a section responsible for training GMFI staff and supervisors, as well as intervening if a particularly diffi cult

situ-ation developed that could not be resolved by the branch supervisor or branch head. Asset and liability management simply meant depositing surplus funds in a savings account at the branch, or borrowing from it if there was a shortage of loanable funds.

Off Java, the sub-district-based model was used in both South Kalimantan and West Nusa Tenggara. Before conversion to BPRs, some GMFIs served villages with motorcycle teams, although the BKKs in South Kalimantan never extended services to the village level in this manner. Some of this difference in history has to do with basic questions of economic scale: villages in South Kalimantan tend to be smaller and spaced further apart than those in West Nusa Tenggara. Much of the difference, though, is related to the combined effect of low levels of capitalisation and the uniquely detrimental interpretation of BI regulations on the development of BKKs in South Kalimantan.

Local government-owned BPRs

As GMFIs have converted to local government-owned BPRs, many have consoli-dated their operations at the sub-district-level offi ce and withdrawn the teams that

previously made banking services available at the village level. Both the GFMIs and BI perceive this to lower risk while still generating reasonable returns—at least until markets are saturated. Certainly, lending at the sub-district offi ce is

easier than dispatching teams each week to the villages. In the best cases, these BPRs have complemented the services of BRI village units by serving somewhat

smaller micro enterprises than the latter would normally reach. In most cases, though, they have tended to focus on lending to salaried workers, especially civil servants. While increasing competition within this market segment and contrib-uting to the fi nancial sustainability of the institution, this has done little to expand

local access to micro credit more generally. In short, even though many GMFIs were reaping considerable profi ts from their village operations without explicit

or implicit subsidies, regulatory interventions have caused a retreat from the vil-lages and a reallocation of resources in pursuit of low-hanging (if not the sweet-est) fruit.

Among GMFIs, sub-district-level BPRs have proven to be the weakest model to date, even in relatively densely populated Java. Current regulations effec-tively require BPRs to be stand-alone organisations, capable of meeting regula-tory, organisational and administrative requirements and their own liquidity and asset–liability management needs, and of managing the internal development of human resources. However, most of the ex-GMFI BPRs had fared much better when they were receiving close support from the provincial development banks before conversion to BPR status. The smaller district-wide BPRs have suffered from similar diffi culties.

Over time, the province-wide BPR model, as exemplifi ed by BPR Jatim in East

Java, may prove to be the most successful of the various types of local government-owned BPRs in terms of sustainability and political non-interference. However, this begs the question: is the new, BPR-based arrangement better and safer than what it replaced—a network of sub-district-based, savings-taking, micro fi nance

institutions closely supervised and supported by the provincial development bank? Without exception, conversion to BPR status has entailed a loss of cover-age at the villcover-age level, while the removal of close operational supervision and the imposition of additional regulatory-related administrative burdens and new forms of political pressure and interference have been detrimental to the sustain-ability and safety of the new BPRs.

The remarks presented here should not be viewed as criticism of BPRs in gen-eral. At the same time, it is important to understand the respective limitations of government-owned and private sector BPRs in terms of performance and opera-tions. The latter are not featured in this paper because they are in effect urban and semi-urban micro fi nance institutions. The overwhelming majority have barely

touched rural areas. Instead, they typically offer competition and choice in the districts and in the largest sub-district-level markets.

Village-owned fi nancial institutions

This paper has identifi ed two successful, sustainable models of village-owned fi nancial institutions: the LPDs of Bali and the BKDs of Java and Madura. Of the

two, the Bali institutions are by far the more dynamic and fully developed. Some of the reasons for the success of Bali’s VMFIs—the close ties to a cohesive, account-able desa adat, traditional Balinese attitudes towards debt and mutual obligation, and a tourism-driven local economy that has remained conducive to micro- and small enterprise development over several decades—would be diffi cult to

repli-cate in other regions. But other factors should be more easily replicable: a win– win accommodation between BI’s prudential and regulatory requirements on the one hand and enabling local legislation on the other; ownership, accountability

and service at the village level; and close support and fi nancial supervision by

a commercial bank, in this case the provincial development bank. In Bali, it has been possible to rely on the strength and organisational capacity of the desa adat; in other areas, more support and closer supervision may be required from the supervising bank, though this need not necessarily impose a fi nancial burden on

it. Aspects of both the Java–Madura and Bali approaches should be incorporated into the development of any new village-based model.

The case for government-owned fi nancial institutions

This study has examined several types of fi nancial institutions delivering micro-fi nance at the village and sub-district levels, including the VMFIs in Java–Madura

and Bali and the GMFIs in Central and East Java, West Nusa Tenggara and South Kalimantan. At some point, however, it is necessary to examine the basic appro-priateness of the institutional form. In short, is there a case for creating or support-ing fi nancial institutions owned by local government? Based on the experience

to date, the answer must be in the affi rmative. In particular, VMFIs and GMFIs

have provided coverage in areas not served by conventional fi nancial institutions.

They are addressing a market failure to profi tably provide vital fi nancial services

to under-served communities.

Furthermore, provincial, sub-district and village offi cials have shown

them-selves willing to support and protect the public purpose of VMFIs and GMFIs in a way not seen with local government-owned BPRs. Some of the reasons for this lie in the nature of local government at the lowest levels: local enough to be responsive to community needs without (yet) being highly politicised. In addi-tion, expectations about profi tability play an important role: local governments

invariably seem to expect a signifi cant dividend from their general-purpose BPRs,

while the special-purpose GMFIs and VMFIs have not been pressed nearly as hard in this respect.

Of course, there are caveats. Not all GMFIs have performed well, and there are dangers inherent in attaching a fi nancial institution to a politicised or

dividend-hungry local government. Furthermore, GMFIs should not have any sort of monopoly power or benefi t from restricted entry of fi nancial institutions in rural

areas; savings and loan cooperatives, rural banks and branch offi ces of

commer-cial banks should be allowed to develop freely. Ultimately, though, these caveats simply mean that the governance and support mechanisms for GMFIs should in the future try to stay closer to the best-case examples mentioned above, and work to avoid the worst.

Experience to date argues for three key attributes of a successful GMFI. First, the institution should be placed at the lowest feasible level of local government (the sub-district or village) to minimise politicisation and a focus on dividend earnings, and to encourage a sense of mission and—in the case of a village—com-munity ownership. For village-level institutions, ownership should be vested in the village. For sub-district-level institutions, majority ownership by the province has encouraged a stronger sense of mission than is the case in district-owned insti-tutions, but at the cost of tensions with the district government. No province has yet attempted to place ownership of its GMFIs with the provincial development bank—an alternative that would appear to carry a number of advantages—pre-ferring instead to exercise ownership directly.

Second, the institution should develop a strong relationship with a commercial bank (or, as a second-best case, a large BPR) that is able to provide both super-vision and institutional support—including management of excess liquidity; a credit line; training and institutional development; and continuous, system-wide monitoring and reporting. While the provincial development bank is usually the

fi rst choice for such a role, other banks with strong experience in rural fi nance

and an adequate branch network in the province could also fi ll this role. Such a

relationship need not be a fi nancial drain on the supervising bank, and has the

potential for signifi cant positive effects on the business growth of the supervising

bank. How to arrange such a relationship in the current regulatory environment is an important question and a major focus of the recommendations below.

Finally, the institution should actively avoid conversion to BPR status. To date, such conversions have inevitably weakened the institution’s sense of mission, eroded the level of effective supervision (and, ultimately, soundness), undermined support arrangements and added to the administrative burden. At the same time, pressures to produce a large annual dividend have caused local government-owned BPRs to redirect their short-term focus away from the villages in favour of lending to salaried employees, and undermined their ability to expand services by reinvesting profi ts.

Minimum required economic scale at the village level

One of the key determinants of the success of GMFI/VMFI-style banking institu-tions is scale. This is important in at least two ways. First, an effective operating model for such institutions must be capable of being scaled down to a very small minimum feasible level of operations. Second, participants and policy makers must also be realistic about the minimum scale of activity needed to support a fully self-sustaining micro fi nance institution. Similarly, cost-effective provision of

support and supervisory services is made much easier when the villages served are clustered relatively close to each other—it is much easier for GMFI village post staff or the VMFI book-keeper to cover a ‘route’ when villages are relatively close to each other.

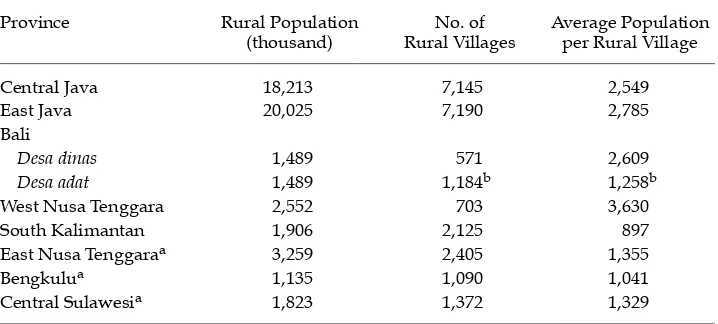

That said, the experience of VMFIs and GMFIs strongly suggests that, beyond a minimum level of activity, village scale may not be a strong predictor of fi nancial

success. This point is illustrated in table 6, which shows the average size of rural villages in the provinces included in this study. On population measures alone, it is not obvious that the VMFIs of Bali should, by far, be the best-performing vil-lage-level institution: the average population of Bali’s rural villages, particularly the desa adat (on which the VMFIs are based), is relatively small compared to that of some of the other provinces studied. At the same time, the statistics for South Kalimantan (and the provinces of interest for future GMFI development) suggest that it may be diffi cult to fi nd very many villages outside the sub-district centre

with the necessary minimum scale of activity to support a village bank or GMFI village service post.

More generally, the VMFIs have shown a strong ability to operate consistently and sustainably at a very small scale—and in economic and social conditions that are not as ‘special’ as those found in Bali. According to a recent sample survey of 96 VMFIs conducted by the authors, most serve between 41 and 220 borrowers. (This range represents the middle 50% of the VMFIs surveyed.) Furthermore, the

survey results and interviews with VMFI supervisors indicate that sustainability can begin at low population levels, at least by Javanese standards. In the survey, only the bottom 10% of VMFI villages—those with less than 1,953 people—have rates of profi tability much below the average. While not too much should be read

into this statistic,15 it does support the basic point that it is possible for VMFIs to

be sustainable while serving a fairly low population base. Reinforcing this point, the survey results suggest that both village participation rates and loan quality— as measured by the median percentage of borrowing households and median annual loss rate, respectively—are negatively correlated with village size. Higher participation and lower loss rates tend to boost the sustainability of VMFIs in smaller villages. In terms of number of borrowers, two-thirds of VMFIs with 50 borrowers or less were profi table, rising to and levelling out at around 90% for

VMFIs with 88 borrowers or more. About 60% of the VMFIs surveyed had at least 88 borrowers.

Qualitatively, supervisors felt that, under the previous book-keeping system, individual VMFIs became comfortably self-sustaining with total outstanding loans of Rp 50–100 million. Under the present book-keeping system, this range might be lower by one-third or more. Using an average loan size of approximately Rp 400,000, this translates into roughly 100 borrowers, most of them making weekly repayments on their loans.

For VMFIs to be successful, it is best to have a cluster of fi ve or six relatively

close to each other so that they can be served by one book-keeper who travels to a

15 Note that this is a measure of short-term profi tability among institutions that have

sur-vived to the present, rather than a comparison of survival rates over time. The sample size was too small to determine statistical signifi cance. A fi nal note: because many of the VMFIs

were still carrying out the book-keeping adjustments described earlier in the text, profi ts

for the current year may have been artifi cially low.

TABLE 6 Average Population per Rural Village, Selected Provinces

Province Rural Population

(thousand)

No. of Rural Villages

Average Population per Rural Village

Central Java 18,213 7,145 2,549

East Java 20,025 7,190 2,785

Bali

Desa dinas 1,489 571 2,609

Desa adat 1,489 1,184b 1,258b

West Nusa Tenggara 2,552 703 3,630

South Kalimantan 1,906 2,125 897

East Nusa Tenggaraa 3,259 2,405 1,355

Bengkulua 1,135 1,090 1,041

Central Sulawesia 1,823 1,372 1,329

a Provinces without GMFIs, but of especial interest for future GMFI expansion.

b Estimate.

Source: Badan Pusat Statistik.