Stockholm Doctoral Course Program in Economics

Development Economics II

Lecture 5

Political Economy of

Development

Masayuki Kudamatsu IIES, Stockholm University

Big question today

How does politics

More specific questions today

1. Why do welfare-enhancing reforms

often get stalled?

2. Is democracy good for

development?

3. What makes democracy work?

1. Why do welfare-enhancing

reforms often get stalled?

• Structural adjustment reforms in

1980s

• Streamlining procedures of setting

up a firm (cf. Djankov et al. 2003)

• Formalizing property rights

• Anti-corruption measures

1.1 Quick literature survey

Basic idea for why welfare-enhancing reform gets stalled

• Winners may propose

compensation for losers

• As welfare (total surplus) increases, winners still better off

• Once reform enacted, winners lose

incentive for compensation

⇒ Winners’ promise not credible

Reform gets stalled because...

• Losers constitute a majority

• Even if losers are a minority:

(1) Small group size solves collective action problem to lobby govt (Olson 1965)

(2) Individuals uncertain whether to win or lose (Fernandez & Rodrik 1991)

• Uncertainty over whether losers will

have political power (Jain & Mukand 2003)

• The ruler’s “career concern” (Majumdar

• These papers look at only one policy reform

• In reality, there are many policies to

reform, whose feasibility may depend on each other

• Caselli and Gennaioli (2008) tackle

1.2 Caselli and Gennaioli

(2008)

Research questions:

• Deregulation of entry

• Improving contract enforcement in

credit market (financial reform)

• Both increase entry and thus

welfare

• But politically feasible?

Why original & important?

• Entry deregulation & financial reform:

• Perhaps two of the most important reforms for development

• Aghion et al. (2008) and Burgess & Pande (2005) for impact evaluations • Only analyzed separately before

• Provide a 1st example of

Model: Demography &

Endowment

• A continuum (of measure 1) of

agents

• Each agent: endowed w/ 1 unit of

labor & managerial talent θ

• Fraction λ: θ = 1 (talented)

• Fraction 1 − λ: θ = θ(≤ 1)

(untalented)

Model: Demography &

Endowment (cont.)

• Fraction η: also endowed w/ a firm

(incumbent)

e.g. Family-owned firm

• Fraction 1 − η: (outsiders)

• None own wealth

Model: Technology

• If agent w/ talent θ owns a firm and

hires l labor (incl. his own):

y = θl1−α

• α: degree of decreasing return to

scale

• See sec. V.B. for constant return to scale

Model: Market for control

• Outsiders can buy a firm from an

incumbent by paying price p

• Each agent can run at most 1 firm

⇒ Talented incumbents cannot buy a

firm from untalented incumbents • Main results would still hold if

otherwise (p. 1227)

• No market for managers

⇒ Incumbent cannot hire talented agent as manager of their firm

Model: Policy variable 1

ε(≥ k): cost of setting up a firm for outsiders

• k(> 0): technologically determined

fixed cost

• If k = 0, no role of market for control (pp. 1206-7)

• ε −k: degree of entry regulation

• Bureaucratic setup costs (incl. bribes) cf. Djankov et al. 2003

Model: Policy variable 2

φ: fraction of borrower’s profit that lenders can recover in case of default

• Quality of financial legislation / contract enforcement

• As no agents has assets, they need to borrow for setting up / buying a firm ⇒ φ ↑: financial reform

• Credit supply: perfectly elastic w/

Model: payoffs

• Workers: w

• Incumbents who don’t sell: π + w

(profit plus his own wage)

• Incumbents who sell: p + w

• Outsiders who set up a firm:

π + w −ε

Model: Timing of events

1. Outsiders: decide whether to

become a firm owner (either by

paying setup cost ε or paying p to

an incumbent) by borrowing money

2. Firm owners: hire workers by

paying wage w

3. Production takes place

4. Borrowers: decide whether or not to

Assumptions

1. η < λ < 1• To focus on whether talented outsiders can set up a firm 2. k = αλα−1

⇒ At first best, no untalented agent runs a firm

• Main results would still hold if

αλα−1

Analysis: How to proceed

• Characterize equilibrium choice of

outsiders by:

f : total # of firms (entrepreneurship) s : share of firms run by talented agents

(meritocracy)

• Initially we have f = η and s = λ

• First best: f = λ and s = 1 (Lemma

Analysis: How to proceed (cont.)

1. Derive payoffs as functions of (f,s)

2. Analyze how (f,s) change with ε

and φ

3. Identify winners and losers from

reforms (ε ↓ and φ ↑)

⇒ Assess political feasibility of

Analysis 1: equilibrium payoffs

a. Derive each firm’s labor demand

given w

b. Solve for eq. w from labor market

clearing

c. Obtain π as a function of exog.

Analysis 1a: labor market

• Firm owner solves:

max

l θl

1−α − wl

• By FOC, the optimal labor demand

by firm owner of talent θ is:

l∗(θ) = �(1 − α)θ w

Analysis 1b: labor market (cont.)

• Labor market clearing:

1 = fsl∗(1) +f(1 −s)l∗(θ)

= f�1 − α w

�α1

(s + (1 − s)θα1)

⇒ Equilibrium wage:

w(f,s) = (1 − α)fα[s + (1 − s)θα1]α

Analysis 1c: profit function

To obtain profit functionπ(θ) = θl∗(θ)1−α − w(f,s)l∗(θ)

Analysis 1c: profit function (cont.)

For talented firm ownersπH(f,s) ≡ αfα−1[s + (1 − s)g]α−1

For untalented firm owners

πL(f,s) ≡ gπH(f,s)

where

Analysis 1c: profit function (cont.)

πH(f,s) ≡ αfα−1[s + (1 −s)g]α−1

πL(f,s) ≡ gπH(f,s)

• ∂πH∂(ff ,s) < 0, ∂πL∂(ff,s) < 0:

⇐ More firms push up wage

• ∂πH∂(fs,s) < 0, ∂πL∂(fs,s) < 0:

Talented incumbent’s payoff

(See Proof of Proposition 3)As f or s goes up:

⇒ Talented incumbents prefer lower f,

Untalented incumbent’s payoff

(See Proof of Proposition 3)As f or s goes up:

• πL(f,s) + w(f,s) is...

• Minimized at w(f,s) = (1−α)gα

• Maxw(f,s) = (1−α)λα could be

larger than this

• Which happens if λ is large

• We’ll see in such a case no one will set up a firm and thus wage does not reach its maximum

⇒ Untalented incumbents prefer lower

Analysis 2: Derive

f

and

s

• An outsider’s decision to

a. Set up a firm by payingε

b. Buy a firm from an incumbent by payingp

• Either way, an outsider needs to

borrow

How much to borrow

Let L be amount of loan, π profit

Analysis 2a: entry

• Outsiders:

• want to set up a firm ifπ(f,s) ≥ ε

• can set up a firm if φπ(f,s) ≥ ε

⇒ Ifφ <1, credit constraint (want to own a firm, but cannot borrow for it)

Analysis 2a: entry (cont.)

Lemma 2: No untalented outsiders set up a firm under assumption 2 (ie.

k = αλα−1)

• This simplifies analysis below

Proof of Lemma 2

• πH > πL

⇒ If some untalented enter, all

talented should have already entered

• πL: largest when 1st untalented

enter after all talented entered (w/ no firm sale)

⇒ If such πL is smaller than ε/φ,

Proposition 1

Assume no market for control. The unique equilibrium is:

• Entry iff φπH(η, λ) ≥ ε

• At least some talented outsiders set up new firms

• No Entry iff φπH(η, λ) < ε

Proposition 1 (cont.)

φπH(η, λ): Amount of money talented agents can borrow if no one sets up a firm in the equilibrium

• If larger than the set-up cost ε,

Corollary 1

Without market for control,

• ε ↓ or φ ↑ ⇒ Both f & s: ↑

• Untalented outsiders won’t set up a firm (lemma 2)

⇒ # of talented outsiders setting up a firm ↑ ⇒ f ↑ & s ↑

• 1st best cannot be achieved

• 1st best: no untalented owns a firm • πL: lowest at ε = k, φ = 1

• But πL > 0,∀f,s (by α > 0)

Analysis 2b: market for control

• Untalented incumbents:

• want to sell if p ≥ πL(f,s)

• Talented outsiders:

• want to buy if πH(f,s) ≥ p

• can buy ifp ≤ φπH(f,s)

⇒ Transaction takes place if

πL(f,s) ≤ p ≤ φπH(f,s) ⇐⇒ φ ≥ g

Analysis 2b: market for control

(cont.)

• Financial reform encourages the

sale of a firm from untalented to talented

• Consistent w/ evidence by Rossi & Volpin (2004)

• p: determined by bargaining power

btw. seller & buyer

• For much of analysis, the exact p

does not matter (fn. 17) • Later, it will be assumed that

Proposition 2

If market for control exists, the unique equilibrium is

• No Sales if φ < g

• NO untalented incumbents sell • No Entry if φπH(η, λ) < ε

• Entry otherwise (by Proposition 1)

• All Sell if φ ≥ g

• ALL untalented incumbents sell • No Entry if φπH(η,1) < ε

Proposition 2 (cont.)

Why all sell, not some sell?• One more untalented incumbent

sells

⇒ Labor demand ↑ (talented demand

more)

⇒ Wage ↑, πH ↓

• But this does not affect the

condition for sale as long as φ ≥ g:

Corollary 2

If φ does not cross the φ = g line,

• ε ↓ or φ ↑ ⇒ Both f & s: ↑ Transition from φ < g to φ ≥ g:

• s jumps up to 1

• This change would be smooth if continuousθ (p.1233)

⇒ πH(f,s) goes down

⇒ Fewer talented agents set up a firm

Consistent w/ empirical findings

(& new empirical implications)

• φ ↑ or ε ↓ ⇒ s ↑

• Djankov & Murrell 2002

• ε ↑⇒ f ↓

• Klapper, Laeven, & Rajan 2004 • Fisman & Sarria-Allende 2004

• φ ↑ may reduce f

Analysis 3: Political feasibility

• Who are the winners and losers

from the two reforms?

• Assumption 3:

• In the status quo (ε0, φ0), the

Winners & Losers from

ε

↓

/

φ

↑

• Outsiders: always win (Prop 4(i))

• Their payoff: at least w(f,s)

• Talented incumbents: always lose

(Prop 4(ii))

• Both φ ↑ & ε ↓ erode πH more than they increase wage

• Maximum wage (w(λ,1))at 1st-best is not large enough to compensate profit loss

Proposition 4 (iii)

Untalented incumbents’ payoff:

• Always ↓ by deregulation

• Forφ < g, wage cannot be large enough to compensate profit loss • Forφ ≥g, price of firm ↓

Why untalented incumbents’

payoff goes up with

φ

↑

?

Once All Sell equilibrium achieved, their payoff: w(f,1) +φπH(f,1)

• No Entry equilibrium: wage

constant at w(η,1) while the firm price increases

• Entry equilibrium: wage goes up

with φ via f ↑ while the firm price is

But this is conditional on large ε0

• For small ε0: financial reform induces entry before All Sell equilibrium achieved

• In this case, untalented incumbents’

payoff goes down with φ ↑ due to

Intuition

• Untalented incumbents:

endogenously compensated by

market for control

• Welfare gain by financial reform: firms run by more talented

• By selling firms to talented,

Implications

• Untalented incumbents: more likely

to support financial reform w/ higher

ε0

⇐ Because higher entry barrier kills

the profit-reducing effect of financial reform

⇒ To enact financial reform, raising ε

Optimal sequence of reform can then be (section IV.C)

• First, financial reform without entry

deregulation

• so untalented incumbents support the reform

• Then entry deregulation

• Now untalented incumbents have

• A very nice policy implication that incorporates political-economy

• But perhaps naive to assume that

political feasibility goes up with # of supports

• What’s the role of political

2. Is democracy good for

development?

• Democracy: perhaps most

important political institutions

• Development assistance

practitioners: often advocate democracy as a means to good governance

What is democracy, BTW?

Definition in this lecture:• A political system in which

Digression: Democracy datasets

• Polity IV or Freedom House

treats different aspects of democracy as

substitutes

• Przeworski et al. (2000)

(recently updated by Cheibub et al. 2010)

treats different aspects of democracy as

complements

cf. Munck and Verkuilen (2002) for

2-1. Evidence

• Large social science literature on

which political regime can achieve higher growth

cf. Przeworski & Limongi (1993) for an early literature survey

• Acemoglu et al. (2008) provide

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

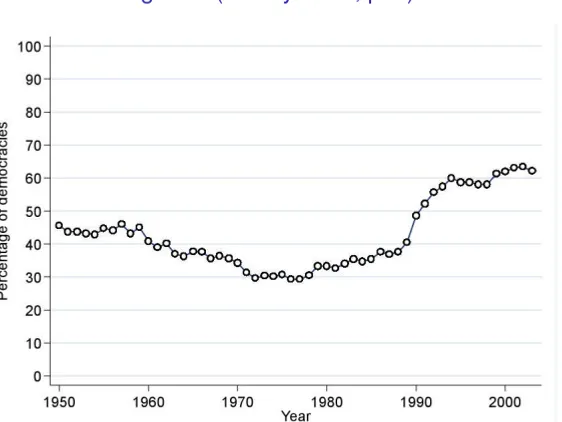

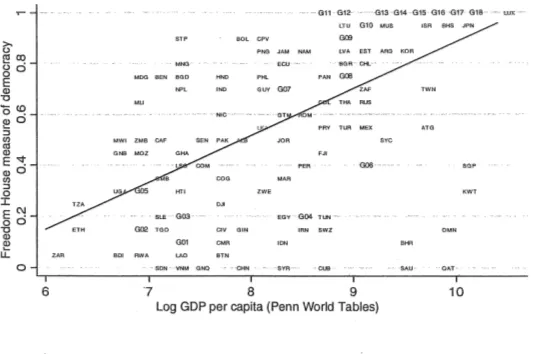

1. Rich countries today: more

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

1. Rich countries today: more

democratic (Fig.2)

• This could be either due to

1. Democracy⇒ Development

2. Development⇒ Democracy

3. 3rd Factor ⇒

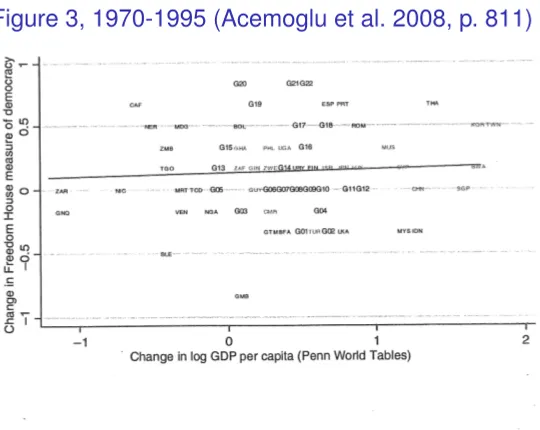

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

2. No correlation between changes in

income and changes in democracy in 20th century

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

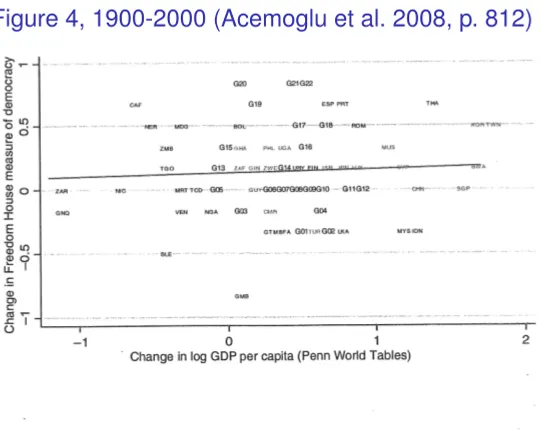

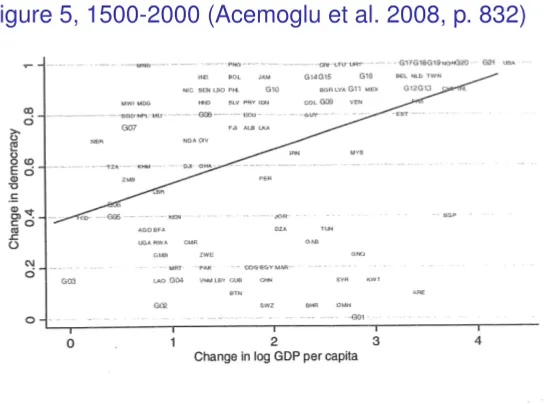

3. Positive correlation between

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

3. Positive correlation in the very long

run: 1500-2000 (Fig.5)

• This could be either due to

1. Very long-run effect of democracy on development

2. Very long-run effect of development on democracy

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

• Correlation with health

• Positive cross-sectionally

• Zero for changes after WWII (Besley & Kudamatsu 2006, Ross 2006)

• Correlation with education

• Positive cross-sectionally

• Zero for changes after WWII, if years of schooling used (Acemoglu et al. 2005)

2-1 Evidence (cont.)

Very difficult to identify causal effect of democracy

• Democracy: endogenous

• education, emergence of middle class, etc. (Lipset 1959)

• transitory negative income shock (Brucker & Ciccone 2011)

• Kudamatsu (2012): use

cross-counry micro panel data on

2-2 Beyond simple comparison

4 reasons for why simple comparison is fruitlessa. Representation theory of politics ⇒ Heterogenous treatment effect

b. Accountability theory of politics

⇒ Complementary institutions to make democracy work

c. One more stylized fact

⇒ Autocracy: highly heterogenous

Digression: 2 views on politics

• Representation

• Conflict of interest among citizens

cf. Persson & Tabellini (2000, ch. 3 & 5)

• Accountability

• Conflict of interest

between govt & citizens

2-2a Representation perspective

Acemoglu (2008)’s model nicely summarizes this perspective for the impact on growth• Firm managers and Workers

• Firm managers prefer

• Low tax rate

• Entry barrier to keep wages low

• Workers prefer

Standard growth theory suggests:

• Tax ↑ ⇒ Investment ↓

⇒ Short-run growth↓

• Entry barrier ↑ ⇒ Innovation ↓

• Tax ↑ ⇒ Investment ↓ ⇒ Short-run growth↓

• Entry barrier ↑ ⇒ Innovation ↓

⇒ Long-run growth ↓

• Autocracy: Firm managers decide policies

1. Tax: low

⇒Short-run growth: high

2. Entry barrier: high

• Tax ↑ ⇒ Investment ↓ ⇒ Short-run growth↓

• Entry barrier ↑ ⇒ Innovation ↓

⇒ Long-run growth ↓

• Democracy: Workers decide policies

1. Tax: high

⇒Short-run growth: low

2. Entry barrier: low

• Impact of democracy on growth has two channels

• Investment • Innovation

• Democracy: good for growth in

sectors where innovation is more important than capital accumulation

⇒ Aghion et al. (2008) provide

evidence consistent with this

• Theory uncovers heterogenous

2-2b Accountability perspective

• Democracy: regularized leadership

contest

• Citizens can replace incompetent

leaders w/ (potentially) better ones

⇒ Incentives for leaders to behave

well

• This argument makes (at least) 3

implicit assumptions

1. Voters know what leaders did ⇒w/o free media, this is unlikely

2. Voters behave as one agent ⇒w/ conflict of interest among voters, this is unlikely

3. Challenger is better than bad-behaving incumbent

⇒ w/o complementary institutions,

2-2c One more stylized fact

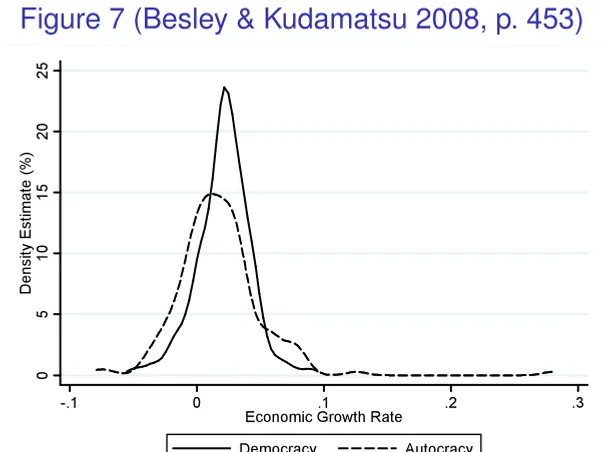

More volatile economic growth in autocracy than in democracy• Performance varies a lot more for

2-2c One more stylized fact

More volatile economic growth in autocracy than in democracy• Performance varies a lot more for

autocracy (Fig.7)

• Jones & Olken (2005): Natural

death of a leader ⇒ Changes in

⇒ Autocracy appears to be VERY heterogeneous

⇒ Not an ideal control group to

2-2d de facto political power

• Acemoglu & Robinson (2008): Rich

may intensify de facto political power to nullify de jure political power of poor

⇒ Regime change may not be

More fruitful questions to ask:

• What makes democracy work?

3. What makes democracy

work?

• Competitive election per se may not

bring benefits to citizens

• What institutions are

complementary to elections?

• Literature has so far identified:

• Free media (or information provision) • Reservation of political office

• Enfranchisement

3-1 Free Media

• Political agency model: citizens

punish incumbents who chose wrong policies

• Unless citizens observe what policy

is chosen, however, they won’t be able to punish

• Role of media crucial to make

3-1 Free Media (cont.)

• Quite a few papers by now

empirically show this

complementary role of media (or information provision in general)

• Besley & Burgess (2002) for newspaper circulation in India

• Ferraz & Finan (2008) for corruption audit in Brazil

• Enikolopov, Petrova, & Zhuravskaya (2011) for independent media in Russia

3-2 Political Reservation

• Citizen-candidate model:

policy-makers cannot commit to electoral platforms

• Disadvantaged groups (women,

minority ethnic groups, etc.) tend to be underrepresented in democratic politics

⇒ Their preferred policies won’t be

3-2 Political Reservation (cont.)

• India has attempted to correct this

by reserving political office to disadvantaged groups

• In 1992, 1/3 of rural municipalities

randomly chosen in a state: only women can become municipality prime minister (Pradhan)

3-2 Political Reservation (cont.)

• Chattopadhyay & Duflo (2004)

empirically show that reservation for women increases adoption of

policies cared by women

• Pande (2003) empirically shows

3-3 Franchise extension

• Median voter theorem: suffrage

extension leads to policy change

• Before WWII, suffrage often first

given to men, then to women

• Women more concerned on child

health than men

• Miller (2008) shows enfranchising

3-3 Franchise extension (cont.)

• Today, all democratic countries

have universal suffrage

• In reality, poor people are effectively

barred from voting

• Illiterate people cannot write a candidate’s name on the ballot • Poll taxes, literacy test in US South

• In this context, electronic voting can be “de facto” enfranchisement

• Fujiwara (2010) estimates its

impact in Brazil

The following pictures are taken from Figures 1 and 2 of

• Using RD design, Fujiwara (2010) finds that due to electronic voting:

• # of invalid votes↓

• public health care spending↑

3-4 Term limit

• Some democracies impose term

limit

• Often due to the nasty dictatorship in the past (e.g. Latin America)

• Ferraz & Finan (2011) show those

Brazilian mayors who cannot run for re-election due to term limit are

3-5 Secret Ballot

• In agrarian society, landlords supply

the votes of their workers in exchange for money, favors, or policies from politicians

• Britain, Germany, France in 19th century

• Chile until 1958

• No secret ballot in these cases

• Ballots have to be obtained from candidates

• Secret ballot makes tenants’ voting choice unobservable to landlords

• Landlords then cannot fire tenants

who voted against their will

• Baland & Robinson (2008) provide

such evidence in Chile: landlord

party’s vote share ↓ after secret

4. What makes autocracy work

• Some developing countries: still

autocracy

• China, Cuba, North Korea, many Gulf states, etc.

• Military coups: still relevant

• Thailand, Fiji, Guinea, Honduras, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Egypt

• See Besley & Kudamatsu (2007,

section 2) for a literature review

• Best paper in this literature so far:

Stylized facts on autocrats

• Extracting enormous rents from

power

• Personal wealth equivalent of country’s foreign debt

• Extensive & very inefficient redistribution

• Buy crops from farmers for way below world price

• Bloated bureaucracy

• Active support from sizable share of

Research question

• What characteristics of autocracy &

Model: demographics

• A continuum of infinitely-lived

citizens of mass 1

• Proportion πA: group A; the rest

group B

• Group identity: observable &

impossible to change (e.g. skin color)

• Leader of group St ∈ {A,B} in

Model: technology & citizens’

Model: leader

S

t’s actions

(policies)

• Tax on each activity: τtSta, τtStb ⇐ No state capacity to tax income

• Patronage to each group: ηStA

t , η StB t

Model: preference

• Group A citizens

(1 −ztA)(ωa − τSta

t > 0, satisfying

R�(ηStA

Model: preference (cont.)

• Group B citizens

(1 − ztB)(ωb − τStb

t )

+ ztB(ωb − θB − τSta

t )

+ R(ηStB

Model: preference (cont.)

• If ousted, leader’s payoff is 0 fromt on

• δ: discount factor for both groups of

Model: political institutions

• Uncertainty of leadership succession in autocracy

• Group j �= St cannot replace leader

Model: Timing of events at

t

1 Leader of St chooses policy vector

Pt ≡ {τtSta,τtStb,ηtStA,ηtStB}

2 Group St decides whether to

support leader, sSt

t ∈ {0,1}

3 Both groups decide whether to

Model: Timing of events (cont.)

4(a) If sSt

t = 1, Pt implemented, payoffs

realize, St+1 = St w/ prob. γSt

4(b) If sSt

t = 0, leader ousted,

Pr ≡ {0,0,0,0} implemented,

Model: discussion on

assumptions

(1) No collective action problem

(2) No repression

(3) Group j �= St never supports leader

of St

• (1) & (2): fine as leader would otherwise steal more

• (3): Why not leader seeks support

Definition of equilibrium

Focus on Markov Perfect Equilibrium (MPE)

• Strategies: contingent only on the

payoff-relevant state variable St &

prior actions within the same period • Exclude history-dependent strategies such as trigger strategy (see sec 3.1)

⇒ Below time subscript t dropped

• State transitions: as described in

Digression: Equilibrium concepts

for repeated games

A repeated game has many SPEs ⇒

Economists focus on a subset of them that are most plausible

1. Stationary SPEs

2. SPEs on the Pareto frontier (& take

a stance on relative bargaining power of players) ⇐Baland & Robinson (2008)

Definition of equilibrium (cont.)

Pure-strategy MPE: set of the following 4 strategies that are best responses to each other• Leader of A: PA = P

• Leader of B: PB = P

• Group A citizens:

σA(S,PS) = {sA,zA}

• Group B citizens:

Analysis: value functions

• Assume S = A w.l.o.g.

• Case of S = B can all be analyzed symmetrically

• Vj(S): value function for group j citizens in state S

• Wj(S): value function for leader of j

in state S

Analysis: switching

• Choice of zB: no impact on

continuation value

⇒ ztB = 1 iff ωb − τAb < ωb −θB − τAa

• Likewise, choice of zA:

Analysis: switching (cont.)

Tax revenue from a citizen of group B

• τAb if zB = 0 ⇐⇒ τAb ≤ θB + τAa

• τAa if zB = 1 ⇐⇒ τAb > θB +τAa

τAb

Tax Revenue

from a citizen

of group B

θB + τAa 45o

Analysis: switching (cont.)

• Same is true for tax revenue from

group A

⇒ Leader sets (τAa,τAb) so that zA = zB = 0

⇒ Upper limit on tax rates:

Analysis: support for incumbent

• If s = 1 (support)

ωa − τAa + R(ηAA)

+ δγAVA(A) + δ(1 − γA)VA(B)

• If s = 0 (oust)

Analysis: support for incumbent

(cont.)

⇒ s = 1 iff

τAa − R(ηAA)

≤ δ(γA − γA)(VA(A) −VA(B))

≡ ΦA

LHS: Net tax payment

Analysis: leader’s problem

max τAa,τAb,ηAA,ηAB

πA(τAa − ηAA)

+(1 − πA)(τAb −ηAB) +δγAWA(A)

subject to

• τAa ≤ θA + τAb, τAb ≤ θB + τAa

• τAa − R(ηAA) ≤ ΦA

Lemma 1

1. ηAB = 0: no transfer to excluded

group

⇐ Excluded group cannot affect leader’s survival

2. τAb = θB + τAa: tax revenue from excluded group maximized

• Excluded group cannot affect leader’s survival

⇒ Leader can tax them until they are indifferent btw. activities a & b

Lemma 1 (cont.)

3. τAa = ΦA + R(ηAA): tax on leader’s group constrained

⇐ Leader’s group would kick leader out if higherτAa than this

• In equilibrium, leader is always supported

⇒ Leader’s objective function:

max ηAA

πA(ΦA + R(ηAA) − ηAA)

Lemma 1 (cont.)

• Excluded group won’t switch as long as τAb ≤θB+τAa

⇒ For each unit of ηAA spent to πA

citizens, tax revenue goes up by

Lemma 1 (cont.)

Over-redistribution to leader’s group: consistent w/ evidence

• Bates (1981, chap. 2-3): African

govts’ food policy

• Food price: set by govt below market price (taxation)

Proposition 1

• τAa depends on θB, γB, γB.

• How to prove

• Lemma 1: τ’s as a function of ΦA,ΦB • Leader’s strategy: best response to

citizen’s support strategy

• τ’s determine citizens’ future payoff and thusΦA,ΦB

• Citizens’ support strategy: best

response to leader’s tax policy strategy • Find the fix point.

• It turns out there’s unique fix point⇒

Proposition 1: intuition

• Suppose ηAA = ηBB = θA = 0

• θB ↑ implies τAb ↑

• by Lemma 1: τAb = θB +τAa ⇐ Group B cannot oust leader A

⇒ Group B fears leader A’s rule

• Uncertain succession process in autocracy ⇒Ousting leader B increases prob. of leader A’s rule (γB −γB > 0)

VB(A) = ωB − τAb +... ↓

Proposition 1: intuition (cont.)

⇒ Leader B can raise τBb

• by Lemma 1: τBb = ΦB +R(ηBB)

⇒ Leader B can raise τBa, too

• by Lemma 1: τBa = θA +τBb

• Even if θA = 0!

⇒ Group A fears leader B’s rule

VA(B) = ωA − τBa + ... ↓

Proposition 1: intuition (cont.)

⇒ Leader A can raise τAa

• by Lemma 1: τAa = ΦA +R(ηAA)

⇒ Leader A can raise τAb, too

• by Lemma 1: τAb = θB +τAa

⇒ Group B fears leader A’s rule

• ... and so on and so forth

(amplification of fear)

• But eventually converges

• δ(γA −γA) < 1,δ(γB −γB) < 1

Proposition 1: intuition (cont.)

• Just one of the groups has

comparative advantage in one economic activity (θB > 0,θA = 0)

• Enough for leader to expropriate

Discussions 1/4

• If γj = γj,∃j ∈ {A,B}, no amplification of fear

⇒ Allows group j = S to discipline

autocrat

Discussion 2/4

• If group j �= S can have a say in

leadership succession (ie. democracy)

⇒ Allows citizens with power to

discipline autocrat

Discussion 3/4

• The model predicts higher tax to

excluded group

• Kasara (2007) finds the president’s

Discussion 4/4

• Leader stays in power w/ high prob.

(γS)

• Why not invest in income taxation

capacity and promote development so tax revenue increases?

• Stationary bandit theory (by McGuire and Olson 1996)

• Taxation capacity & long time horizon

⇒ Autocrat has incentive to promote development to increase tax revenue

Conclusion / Future research

• No more simple comparison btw.

democracy & autocracy

• Identify institutions complementary

to competitive popular elections

• Explain heterogenous

performances of autocracy

Future research (cont.)

• Understand gray zone cases

(“competitive authoritarianism” or “electoral autocracy”)

e.g. Afghanistan, Venezuela,

Kenya, Zimbabwe, Iran, Russia, etc.

• When govt represses opposition?

Future research (cont.)

• Political selection: if opposition candidates are bad, incumbents have no incentive to behave well

• But we know little about what can

improve the pool of candidates • Ferraz & Finan (2011): higher wage

attracts wealthy & educated

candidates for municipal legislature in Brazil

Future research (cont.)

• What political institutions can

sustain long-run economic growth

• Growth boom and bust

• Bust often as a result of conflict over redistribution

• In the 1980s, East Asians managed to avoid such conflict while Latin

References for Lecture 5: Political Economy of Development

Acemoglu, Daron. 2008. “Oligarchic versus Democratic Societies.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6(1): 1-44. !

Acemoglu, Daron et al. 2005. “From Education to Democracy?.” American Economic Review 95(2): 44-49. !

Acemoglu, Daron et al. 2008. “Income and Democracy.” American Economic Review 98(3): 808-842. !

Acemoglu, Daron, Mikhail Golosov, and Aleh Tsyvinski. 2011. “Power fluctuations and political economy.” Journal of Economic Theory 146(3): 1009-1041.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2008. “Persistence of Power, Elites, and Institutions.” American Economic Review 98(1): 267-293. !

Aghion, Philippe, Alberto Alesina, and Francesco Trebbi. 2008. “Democracy, Technology, and

Growth.” In Institutions and Economic Performance, ed. Elhanan Helpman. Harvard University Press.

!

Aghion, Philippe, Robin Burgess, Stephen J Redding, and Fabrizio Zilibotti. 2008. “The Unequal Effects of Liberalization: Evidence from Dismantling the License Raj in India.” American Economic Review 98(4): 1397–1412.

Baland, Jean-Marie, and James A. Robinson. 2008. “Land and Power: Theory and Evidence from Chile.” American Economic Review 98(5): 1737-1365.

Baland, J. and Robinson, J. 2011. 'The Political Value of Land: Democratization and Land Prices in Chile'. CEPR Discussion Paper no. 8296.

Baldwin, Kate. 2010. "Why Vote with the Chief? Political Connections and the Performance of Representatives in Zambia" http://plaza.ufl.edu/kabaldwin/why_vote_with_the_chief.pdf

Banerjee, Abhijit V., Paul J. Gertler, and Maitreesh Ghatak. 2002. “Empowerment and Efficiency: Tenancy Reform in West Bengal.” Journal of Political Economy 110(2): 239-279.

Banerjee, Abhijit V., Selvan Kumar, Rohini Pande, and Felix Su. 2011. "Do Informed Voters Make Better Choices? Experimental Evidence from Urban India"

Banerjee, Abhijit, and Kaivan Munshi. 2004. “How Efficiently is Capital Allocated? Evidence from the Knitted Garment Industry in Tirupur.” Review of Economic Studies 71(1): 19-42.

Banerjee, Abhijit V., and Rohini Pande. 2009. "Parochial Politics: Ethnic Preferences and Political Corruption."

Besley, Timothy. 2006. Principled Agents? The Political Economy of Good Government. Oxford University Press. !

Besley, Timothy, and Robin Burgess. 2002. “The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness: Theory and Evidence from India.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117: 1415-1451. !

Review 96(2): 313-318. !

Besley, Timothy, and Masayuki Kudamatsu. 2007. “Making Autocracy Work.” CEPR Discussion Paper no. 6371.

Besley, Timothy, and Masayuki Kudamatsu. 2008. “Making Autocracy Work.” In Institutions and Economic Performance, ed. Elhanan Helpman. Harvard University Press.

Besley, Timothy, and Torsten Persson. 2011. “The Logic of Political Violence.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(3): 1411 -1445.

Besley, Timothy, Torsten Persson, and Daniel M Sturm. 2010. “Political Competition, Policy and Growth: Theory and Evidence from the US.” Review of Economic Studies 77(4): 1329-1352.

Brollo, Fernanda, Tommaso Nannicini, Roberto Perotti, and Guido Tabellini. 2013. “The Political Resource Curse.” American Economic Review 103(5): 1759–96.

Brückner, Markus, and Antonio Ciccone. 2011. “Rain and the Democratic Window of Opportunity.” Econometrica 79(3): 923-947.

Burgess, Robin, and Rohini Pande. 2005. “Do Rural Banks Matter? Evidence from the Indian Social Banking Experiment.” American Economic Review 95(3): 780–95.

Caselli, Francesco, and Nicola Gennaioli. 2008. “Economics and Politics of Alternative Institutional Reforms.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(3): 1197-1250.

Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra, and Esther Duflo. 2004. “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India.” Econometrica 72(5): 1409-1443. !

Cheibub, José, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Vreeland. 2010. “Democracy and dictatorship revisited.” Public Choice 143: 67-101.

Engerman, Stanley L., and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. 2005. “Colonialism, Inequality, and Long-Run Paths of Development.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 11057.

Enikolopov, Ruben; Petrova, Maria and Zhuravskaya, Ekaterina. 2011. "Media and Political Persuasion: Evidence from Russia," American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Fernandez, Raquel, and Dani Rodrik. 1991. “Resistance to Reform: Status Quo Bias in the Presence of Individual-specific Uncertainty.” American Economic Review 81(5): 1146-1155.

Ferraz, Claudio, and Frederico Finan. 2008. “Exposing Corrupt Politicians: The Effect of Brazil's Publicly Released Audits on Electoral Outcomes.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(2): 703-745. !

Ferraz, Claudio, and Frederico Finan. 2011. “Electoral Accountability and Corruption: Evidence from the Audits of Local Governments.” American Economic Review 101: 1274-1311.

Fujiwara, Thomas. 2010. “Can Voting Technology Empower the Poor? Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Brazil.” Unpublished paper.

Glaeser, Edward L., Giacomo Ponzetto, and Andrei Shleifer. 2006. “Why Does Democracy Need Education?.” NBER Working Paper 12128. !

Jain, Sanjay, and Sharun W. Mukand. 2003. “Redistributive Promises and the Adoption of Economic Reform.” American Economic Review 93(1): 256-264.

Jones, Benjamin F., and Benjamin A. Olken. 2005. “Do Leaders Matter? National Leadership and Growth Since World War II.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(3): 835-864. !

Kasara, Kimuli. 2007. “Tax Me If You Can: Ethnic Geography, Democracy, and the Taxation of Agriculture In Africa.” American Political Science Review 101(1): 159-172. !

Kudamatsu, Masayuki. 2012. “Has Democratization Reduced Infant Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from Micro Data.” Journal of the European Economic Association 10(6): 1294–1317.

Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1959. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53(1): 69-105. !

List, John A., and Daniel M. Sturm. 2006. “How Elections Matter: Theory and Evidence from Environmental Policy.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(4): 1249-1281.

Majumdar, Sumon, and Sharun W. Mukand. 2004. “Policy Gambles.” American Economic Review 94 (4): 1207-1222.

Martinez-Bravo, Monica. 2010. "Appointed Officials and Consolidation of New Democracies: Evidence from Indonesia"

http://www.webmeets.com/files/papers/SAEE/2010/129/2010_06_01_MonicaMB_AppOfficials.pdf

Martinez-Bravo, Monica, Gerard Padró-i-Miquel, Nancy Qian, and Yang Yao. 2011. "Do Local Elections in Non-Democracies Increase Accountability? Evidence from Rural China”

McGuire, Martin C., and Mancur Olson. 1996. “The Economics of Autocracy and Majority Rule: The Invisible Hand and the Use of Force.” Journal of Economic Literature 34: 72-96. !

Miller, Grant. 2008. “Women's Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(3): 1287-1327. !

Munck, Gerardo L., and Jay Verkuilen. 2002. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices.” Comparative Political Studies 35(1): 5-34. !

Munshi, Kaivan. 2011. “Strength in Numbers: Networks as a Solution to Occupational Traps.” The Review of Economic Studies 78(3): 1069 -1101.

Olson, Mancur. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press. !

Padro-i-Miquel, Gerard. 2007. “The Control of Politicians in Divided Societies: The Politics of Fear.”

Review of Economic Studies 74: 1259-1274. !

Pande, Rohini. 2003. “Can Mandated Political Representation Increase Policy Influence for Disadvantaged Minorities? Theory and Evidence from India.” American Economic Review 93(4): 1132-1151. !

Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 2000. Political Economics: Explaining Economic Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. !

Przeworski, Adam et al. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge University Press. !

Przeworski, Adam, and Fernando Limongi. 1993. “Political Regimes and Economic Growth.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7(3): 51-69. !

Robinson, James A, and Ragnar Torvik. 2009. “The Real Swing Voter's Curse.” American Economic Review 99(2): 310-315. !