W

AGES AND

W

AGE

D

ETERMINATION

IN

2001

MARTINJ. WATTS*

T

he number of employees covered by certified agreements increased during 2001, but wage determination remained fragmented. The inflationary impact of higher oil prices and the depreciation of the Australian dollar in the second half of 2000, when the economy was also absorbing the impact of the GST, threatened the wage targets of the Reserve Bank. Contrary to expectations, wage growth remained modest. The Commission again adopted a compromise Safety Net Decision in May.The review concludes that, notwithstanding the improvement in the conditions of employment of some non-standard employees following successful cases brought to Federal and State Commissions, the balance of forces between employers and employees has fun-damentally shifted over the last decade and this has impacted on wage outcomes. This reflects a combination of workplace reform, in particular the Workplace Relations Act, and the associated structural change in the labour market.

Wages in 2001 continued to be determined in a fragmented manner via the award safety net, union and non-union certified agreements and individual contracts. Wage growth was modest and within the Reserve Bank’s target range, so that, despite the impact of the introduction of the GST in July 2000, high oil prices and the low value of the Australian dollar, inflationary pressures remained rela-tively weak throughout 2001. Consequently the Reserve Bank’s main concern was maintaining the momentum of economic growth through interest rate cuts at a time when the growth rate across the OECD countries was declining (OECD 2002), accentuated by the uncertainty created by the terrorist attacks in early September. Australia’s growth rate proved more resilient, although there were a number of important corporate collapses during the year, including HIH, One-Tel and Ansett Airlines.

The equity of the wages system was again under the spotlight in the annual Safety Net Case in May 2001 with many of the same economic and social argu-ments being mounted as in 2000. The Commission again found the middle ground between the claims of the ACTU and the Joint Coalition Governments (the Federal Government and the Governments of the Northern Territory and South Australia). In a difficult market environment, a number of companies, including Qantas, attempted to freeze or, in the case of the Kilcoy Pastoral Company, even reduce the nominal wages of their employees, thereby cutting their real wages.

During 2001 a series of decisions made by the Federal and State Industrial Relations Commissions (IRCs) improved the conditions of employment of non-standard employees, despite the opposition of the Federal Government. Federal Government legislation, including the Workplace Relations Act (1996), however, along with structural changes in the labour market, some of which have accelerated since the introduction of enterprise bargaining, appear to have fundamentally shifted the balance of power, with unions unable to provide real protections to their members (Long 2001). In the following sections I shall examine the trends in wage outcomes in the context of the macroeconomic environment and also examine some of the industrial relations developments in more detail.

THE MACROECONOMIC BACKGROUND

The growth prospects of the world economy deteriorated during 2001, with the USA entering recession after a long period of boom conditions, and low unemployment rates. The annual OECD growth rate fell from 3.8% to Sep-tember 2000, down to 0.8% over the following year (OECD 2002). The Australian economy proved to be more resilient with the corresponding growth rates being 3.04% and 2.45% in the 12 months to September 2001 (RBA 2002). Wage growth of 3.5%–4.5% during the year was at the lower end of the Reserve Bank’s acceptable range (RBA 2001).

The wage outcomes in 2001, which are outlined in the next section, should be understood in the context of the underlying institutional arrangements, reflect-ing legislative changes and AIRC and Federal Court decisions, and against a back-drop of the underlying macroeconomic conditions.

Monetary policy

The annual rate of inflation for 2000 was 5.8%. The underlying rate was just above 2%, if the GST effect was excluded, which was lower than expected. Despite high oil prices, the weak Australian dollar and the possible flow through of higher import prices, price inflation remained low, because the capacity of firms to pass on rising costs was inhibited by the weakening in demand. Thus the Reserve Bank was not confronting a stagflationary environment that would have posed greater problems for policy making.

Analysts noted that policy makers showed a greater willingness to make sub-stantial and swift shifts in monetary policy than was the case until the mid-1990s. This could merely reflect the more stable inflationary environment and the reduced likelihood of a sharp change in international projections of growth.

The inflation rate was 2.5% to the September quarter 2001, but the Reserve Bank estimates that it had increased to 3.0% by November, following cost pres-sures, reflecting the decline in the exchange rate since 1999 and higher oil prices (RBA 2001: 66). The inflation outlook remains uncertain, but there is no evidence of wage pressures. Import prices have declined, possibly due to weak-ening global demand, but reductions in oil production may force oil prices up again. On the other hand, commercial insurance premiums have increased sig-nificantly since the events of September, and wholesale electricity prices have also risen (RBA 2001: 66–67). Projected annual growth to June 2002 was 3%, despite the reduced growth of the international economy.

WAGE DETERMINATION IN2001

In this section we examine the coverage of different forms of wage determin-ation and the associated rates of money wage growth, along with the institutional and legislative developments during the year which have impacted on the process of wage determination.

The coverage of agreements

The first comprehensive ABS data set on the distribution of employees across different types of Federal and State agreements and the associated rates of pay was released in March 2001 (ABS 2000). It revealed that in May 2000, the most common form of wage setting was unregistered individual agreements (38.2%) which included over-awards, followed by registered collective agreements (35.2%) and awards only (23.2%). Wooden (2001a) argues that workers who receive pay over and above that specified in a registered collective agreement would be classified as being subject to an unregistered agreement, so the extent of registered collective agreements may be understated. Registered individual agreements (1.8%) and unregistered collective agreements (1.5%) were the least common pay setting methods (ABS 2000: 44).

Carlson et al. (2001) note that unregistered agreements are essentially com-mon law contracts. The Workplace Relations Act (WRA) was designed to shift labour relations away from specialised tribunals into the common law domain. Golden (2000) argues that the non-registration of agreements could make their enforcement difficult if challenged.

Registered individual agreements in the public sector (3.0%) covered twice the share of employees as compared to the private sector (1.5%). Registered collec-tive agreements dominate public sector wage setting (83.2%), while unregistered individual agreements are most significant in the private sector (54.2% of males, and 40.9% of females). Also awards covered nearly 30% of females compared to 17% of males.

Male and female part-time employees were more likely to be subject to awards (39.9% in total) and less likely to be operating under unregistered individual agreements than their full-time colleagues (ABS 2000: 45 and unpublished data). This disparity is reflected in a significantly higher percentage of male and female full-time workers who were subject to individual registered and unregistered agreements.

Individual agreements, both registered and unregistered, predominated in firms with less than 100 employees, whereas collective agreements, both registered and unregistered, covered the highest percentage of employees in larger firms.

For all employees, individual agreements are associated with the highest mean average weekly total earnings (AWTE). Using the shares of total employment by occupation in May 2000 as uniform occupational weights in the calculation of the AWTE for all employees across different types of agreement shows that collective agreements yield the highest mean wages. Thus the incidence of dif-ferent bargaining streams across occupations is a major influence on the overall wage relativities between individual and collective agreements.

The ABS data, while a good source of detailed cross-sectional information across both State and Federal registered agreements, as well as unregistered agree-ments, do not provide an indication of trends in the types of agreement being negotiated and these data are only generated every two years. These data from May 2000 would be a good guide, however, to the pattern of coverage in 2001. On the other hand, more recent data on coverage by different types of agree-ment are fragagree-mented. The Departagree-ment of Employagree-ment, Workplace Relations and Small Business (DEWRSB) collects data on registered Federal agreements and the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training (ACIRRT) collects data on registered State and Federal agreements.

New Federal enterprise agreements in the September quarter represented 2.1% of total employees, whereas employees covered by all existing Federal agreements represented 17.9% of all employees (DEWRSB 2001). This compared with an estimated 37% of all employees covered by agreements registered by both Federal and State Industrial tribunals in May 2000 (ABS 2000). There were 11 755 Federal wage agreements current at 30 September 2001, covering an esti-mated 1 362 100 employees. ACIRRT (2001: 6) report that 3504 employers had AWAs approved to the end of August 2001. Next year will be challenging because over 6300 private and public sector Federal agreements will be expiring (DEWRSB 2001).

Money wage growth

Since the advent of enterprise bargaining it has become very difficult to inter-pret aggregate wage data. Many employees have unregistered agreements, wage increases may be granted in exchange for trade-offs in other conditions and there are major compositional changes occurring in the workforce (Burgess 1995).

inflationary pressure, which could have led to a tightening of monetary policy. The index measures hourly wages net of bonuses and, in contrast to measures of average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE), is independent of composi-tional changes, because it is based on a fixed basket of jobs, which, however, includes part-time jobs. As noted above, wage determination for part-time employees differs markedly from that of full-time employees. Annual increases in the index ranged from 4.5% for Electricity Gas and Water to 2.3% for Retail Trade. The other ANZSIC industries each averaged in excess of 3% growth.

DEWRSB (2001) also reported that there was no evidence of an acceleration of wage growth during 2001, with Federal wage agreements formalised in the September quarter paying an average annualised wage increase (AAWI) of 3.9%, the same rate as in the June quarter. The AAWI per public sector employee in the September quarter 2001 was 4.0%, as compared to the private sector increase of 3.8%. The AAWI per employee to the September quarter for all existing agree-ments was slightly lower at 3.7%. In September 2000, the AAWI for new Federal agreements exceeded 4.0%, based on the DEWRSB (2000) survey, but other-wise the implementation of the GST in July 2000 appears to have had little resid-ual impact on wage settlements in the subsequent quarters.

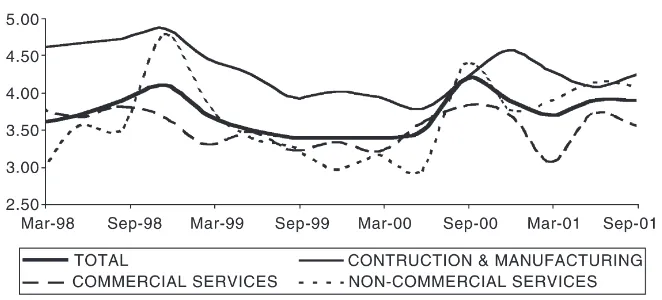

Figure 1 shows quarterly AAWIs for agreements formalised in the corre-sponding quarter across industry groups from March 1998 to September 2001. 232 TH E JO U R N A L O F IN D U S T R I A L RE L AT I O N S June 2002

Notes: Manufacturingand constructionare equivalent to the ANZSIC industries. Commercial services: wholesale; retail; accommodation, cafes, restaurants; transport; communications; electricity, gas and water; finance and insurance; property and business; cultural and recreation; and personal and other. Non-commercial services: education and health, government administration and defence and community services.

The AAWIs are calculated as a weighted sum of the AAWIs per employee per ANZSIC industry with the weights given by the corresponding employment shares.

Source: DEWRSB (2001, various issues), author’s calculations.

Figure 1. AAWI per Employee of Federal Agreements formalised within the

Construction and manufacturing consistently yield the highest AAWIs. Non-commercial services have exhibited major fluctuations over this period, which is surprising given that this industry group consists of public sector employment. Commercial services have generally exhibited the lowest AAWI, but this group comprises somewhat heterogeneous industries, ranging from Wholesale and Retail Trade to Finance and Insurance.

ABS trend estimates reveal that full-time adult AWOTE for males and females rose by 5.1% and 5.8% respectively in the 12 months to August 2001, whereas full-time adult total earnings for males and females rose by 4.7% and 5.2% respec-tively (ABS 2001b). There have been fluctuations in the gender AWOTE ratio for full-time adults over the last decade, but it has remained between 83 and 85%, based on a four quarter moving average (Preston 2001b). In August 2001 the ratio for the quarter was 84.7% (ABS 2001b: 4). Full-time AWOTE for the pri-vate and public sectors rose by 5.6% and 5.1% respectively over the same period (ABS 2001b). Thus there was a discrepancy between relative annual rates of growth of wage costs and AWOTE growth. Full-time adult AWOTE of $837.60 in August 2001 were more than double the new Federal minimum wage of $413.40.

The modest annual increase in the Wage Cost Index to September and the similar increase for all Federal agreements over this period would imply that State registered agreements and unregistered agreements have also exhibited a modest increase over this period.

The September 2001 issue of the quarterly ACIRRT ADAM report was avail-able at the time of writing. It provided data for agreements made in the June 2001 quarter. The report revealed that industry AAWI for all current collective agreements at the end of June 2001 lay in the range of 3.3% (Agriculture, Community Services, Recreational and Personal Services) and 4.5% (Mining/ Construction) (ACIRRT 2001: 5).

Disabled workers employed under the supported wage system were granted a minimum $3 per week pay increase in May by the AIRC, following an applica-tion by the ACTU. This raised the minimum wage to $53 per week (Workforce 2001, 1304, May 18: 3).

Limited data are available for wage outcomes under AWAs. For currently oper-ating AWAs approved to the end of 2000, based on a sample of 83 AWAs, the average annual wage increase was 2.2%, with the public sector rate being 3.1% and the private sector rate 1.9% (ACIRRT 2001: 6).

Mercer Cullen Egan Dell (2001) reported that the annual increase in office workers’ wages to September was 4.4% and the growth in executive salaries remained about 4.75%. The difference between the annual rates of growth of public sector senior managers’ base salary and adult AWOTE has declined over the last decade, but the absolute difference continues to increase. The effective increase in the former would be understated due to share options and other benefits. During 2001 there were cuts to performance bonuses which reduced the packages of some high profile executives (Cave 2001).

September quarter 2001 after reaching a peak of over 13% in December 2000. The percentage of agreements formalised in the quarter that included CPI related clauses peaked at over 18% in December 2000. The decline in the percentage of new agreements with CPI related clauses signifies less concern on the part of employees about the future rate of inflation. It would also tend to reduce the inertia in the prevailing inflation rate.

The living wage case

In November 2000 the ACTU filed its Living Wage Claim under the Workplace Relations Act (1996). The peak body requested a $28 per week increase in award rates of pay up to and including the equivalent of skill level classification C10 in the Metal Industry Award and a 5.7% increase in the higher classifications (AIRC 2001: para 2). The Labor State Governments (LSGs) supported the ACTU’s claim, but gave the Commission some latitude to reduce the adjustment to awards (AIRC 2001: para 9).

The Joint Coalition Governments (JCGs) rejected the ACTU claim, arguing that an increase of $10 should be available, on application, to minimum classi-fication rates at or below the C10 classiclassi-fication, to be fully absorbed into over-awards including those from enterprise agreements and informal overover-awards (JCG 2001: para 1.12). All industry groups favoured a more modest increase, with increases confined to lower paid workers (AIRC 2001: para 5). It was observed that the number of employees covered by awards had fallen from 68% 10 years ago to less than 25% in May 2000 (JCG 2001: para 2.1).

An analysis of the arguments presented to the Commission is insightful because it conveys the underlying beliefs of the major players about the functioning of the wage system. However, they tend to embellish and repeat their arguments from previous Safety Net Cases.

Some of the major issues addressed in the submissions were 1) the magnitude of the ACTU’s demand, and its impact on the macroeconomy; 2) the economic outcomes of low wage workers; 3) the identity of the workers who would benefit from the Safety Net Adjustment (SNA); and 4) the appropriateness of the wage system, rather than the social security system, in addressing the needs of the low paid. We address each of these issues briefly below.

1. Macroeconomic conditions

The AIRC concluded that there was little dispute about the major factors con-tributing to the slowdown, namely: ‘the transitional effects of the GST, evident most strongly in building and construction sector activity, the lagged effect of tighter monetary policy of late 1999 and early 2000 and the impact on the timing of economic activity related to the Sydney Olympic Games’ (AIRC 2001: para 44), but the parties disagreed over the future macroeconomic prospects. The AIRC also noted that with the exception of the 3rd quarter of 2000, the AAWIs of all current Federal agreements were less than 4% (AIRC 2001: para 52).

The JCG noted that only 1.2% of award recipients were employed in the four highest productivity growth sectors, whereas 45% of recipients were employed in three of the four lowest productivity growth sectors. On the other hand, draw-ing on a recent paper by Gruen (2000), the AIRC claimed that the sectors with a high proportion of award-reliant employees made a significant contribution to the increase in overall productivity growth (AIRC 2001: para 56). The AIRC concluded that there has been a general increase in productivity growth in all sectors1with the low productivity sectors contributing the most to the growth

in productivity. Of key importance here is the margin between productivity per worker and the corresponding award wage, along with fixed costs per worker. This is not revealed by examining just the distribution of productivity and wage increasesacross sectors.

In recent econometric work, Mitchell et al. (2002) found that productivity growth across industries had only been partly passed on in the form of lower prices and/or higher nominal wage outcomes in Australia over the period 1984–2001. Thus businesses had been using the productivity gains to expand their margins. The share of the gross operating surplus out of national income remained high, but profits growth over the 12 months had slowed prior to the Living Wage Case (AIRC 2001: para 58) which would reflect the slower growth of output.

The JCG noted that the ACTU’s claim across the different job classifications was much higher than the prevailing growth in the Wage Cost Index (JCG 2001: Table 6.1). The SNA decision would flow on to 1.8 million employees directly or indirectly via State cases. Partial wage increases would also occur where the prevailing over-award was less than the SNA. A number of parties noted that flow-on might occur to rates of pay under agreements and to over-award pay-ments, due to strong bargaining by workers seeking to maintain intra-firm relativities, particularly if individual firms operated more than one system of pay determination (JCG 2001: para 6.5). Also Safety Net Adjustments were some-times passed on by employers when they were not required to do so. On the other hand, not all award recipients received SNAs.

Both the ACTU and the JCG arrived at estimates of less than 1% growth of aggregate wage costs arising from the ACTU’s claim, but the Commission noted that there was no completely reliable and accepted cost estimate (AIRC 2001: para 82).

The AIRC (2001: para 65–66) concluded that the economic fundamentals were sound but there were weaknesses in some sectors, as well as the international economy, and continuing uncertainty about the effect on business confidence from the decline in GDP. Thus caution was warranted in the determination of the Safety Net Adjustment.

2. The level of wages and the extent of poverty

Buchanan and Watson (2000) found that there was a rise in the proportion of workers on low hourly rates of pay in the 1980s and early 1990s, but that the SNAs handed down in the late 1990s sustained a floor beneath working poor and ‘protected workers from worst excesses of deregulation’. The Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) quoted the latest National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling model for the Smith Family which showed that in 1999, 5% of children and 3.9% of adults living in wage earning households lived in poverty, but they represented 19% of all people living in poor households (AIRC 2001: para 118).

The Australian Industry Group claimed that low income workers had received benefits from tax cuts and lower interest rates (AIRC 2001: para 110). This view implies that award adjustment is an act of charity because it is not the outcome of market processes, rather being the consequence of a structural flaw in the current wages system (Watts 2001a). The ACTU pointed out that high wage earners had not moderated their wage demands due to the tax cuts received from the implementation of GST, which were heavily biased to the high paid anyway, so tax cuts to the low paid should not impact on the size of the SNA (AIRC 2001: para 108). Given that the size of the SNA should broadly reflect wage and productivity trends in the economy, the ACTU argument is justified.

The State Labor Governments (SLGs) and the JCG disagreed about the extent of earnings mobility at the bottom of the labour market. The SLGs noted that, with the growth of non-standard employment, low wages were more likely to be entrenched (AIRC 2001: para 109). In their submission, ACOSS noted that an adequate minimum wage and social security system were important for the grow-ing cohort of casual and part-time workers, and that intermittent work was preva-lent, which blurred the employed/unemployed distinction (AIRC 2001: para 118; see also Preston 2001b: 169). Intermittent workers were unlikely to benefit from industry or collective bargaining, given the tenuous nature of employment. ACOSS argued that the minimum wage should be set above the poverty level for a single person, to provide a fair reward for work and to preserve work incen-tives for the unemployed. They advocated a substantial rise in the minimum wage to ensure it did not fall behind average earnings movements.

The AIRC acknowledged that there were people on low wage incomes who faced difficulties and this would be taken into account. The exact number of people in this category was unimportant (AIRC 2001: para 126).

3. The coverage of the SNA

The JCG and some industry bodies continued to argue that any safety net adjust-ment should be confined to low paid workers (equal to and less than the C10 classification in the case of the JCG), rather than being available to all award reliant employees. This issue raised the broader question as to the role of the award system within the broader structure of wage determination.

allowable award matters under the WRA, so they are relevant features of a fair structure of minimum wages that the AIRC must maintain.

In addition, the system of awards plays an important role in the no-disadvantage test. Under the test, agreements for which certification is required (under other divisions of the Act) are compared with appropriate safety net awards to ensure that there has not been a reduction in an employee’s terms and condi-tions of employment (AIRC 2001: para 137). Waring and Lewer (2001: 2) argue that, through successive rounds of legislation during the 1990s, the no-disadvantage test has been diluted. Also with award simplification and the grow-ing disparity between award wages and agreement outcomes, the benchmark has deteriorated, which has further weakened the effectiveness of the test.

The JCG (2001: para 5.21) argue that the structure of awards is, or should be, irrelevant to most employees in higher job classifications. If an employee is dissatisfied with her/his job s/he can leave and go to another employer. They assert that most employees have bargaining power because turnover imposes costs on employers. An employee who is paid the award lacks effective bargain-ing power if this represents less than her/his marginal product, and s/he is unable to move to an employer where the true marginal product will be paid. The JCG argue that this would be rare for employees who are paid the award rate and earn more than C10 (para 5.23). This explains why no OECD country has protection for skilled employees in the form of higher minimum wages (para 5.22).

Orthodox economic theory underpins the JCG view. Labour is conceptualised to be a factor of production, which is subject to the impersonal forces of markets (Carlson et al. 2001). Under common law ‘the worker and employer should basically be free to decide on the content of their relationship’ (Moore 2000: 140). Thus, following the WRA, the reduced role for tribunals and the decline in union involvement in the bargaining process is designed to give primacy to the influence of market forces in the determination of wages and conditions. Equity and social justice issues are picked up by other legislation (Carlson et al. 2001).

Thus the labour market is alleged to work reasonably well, with the prevail-ing award structure reflectprevail-ing the marginal product of most workers in their corresponding job classifications above C10. If a worker’s value exceeds the award, then an over-award would be paid, but there is no justification for absorbing the over-award through a safety net adjustment of the award.2Watts (2001a)

The AIRC reaffirmed its view from its May 2000 decision that the cut-off at C10 would not better target the benefits of the SNA, but the SNA did assist in meeting the needs of the low paid. The presence of two or more wage earners in a family meant that there was no longer a simple relationship between the employee’s income and household income (AIRC 2001: para 127).

4. Wages v. social security

The JCG argued that unemployment was the main cause of poverty, rather than low wages, and that the ACTU claim could raise unemployment, particularly for low wage employees for whom there is a high elasticity of demand. The Australian Industry Group was quite explicit that any social problems of the low paid should be addressed by the social security system (AIRC 2001: para 110).

If the problems of the low paid were to be resolved via social security bene-fits, indexed to average wage growth to allow for real growth, then higher paid award reliant employees, who were unable to negotiate wage increases, would still be neglected. Watts (2001a: 188) noted that, despite its resistance to signi-ficant wage increases for the low paid, the JCG had shown little interest in the proposals of the Five Economists to freeze the awards of the low paid and pro-vide tax credits for those in employment (Dawkins et al. 1998). Both Apps (2001) and Inglis (2001) are unconvinced that the introduction of an income tax credit system in Australia could be justified.

The decision

In its fifth Safety Net Adjustment since the Workplace Relations Act (1996), the Commission awarded a $13.00 per week increase in award rates up to and includ-ing $490.00 per week; a $15.00 per week increase in award rates above $490.00 per week up to and including $590.00 per week; and a $17.00 per week increase in award rates above $590.00 per week. The Federal minimum wage was increased by $13 to $413.40 per week. The usual conditions applied, including the full absorption of the award in over-awards. The AIRC concluded that given the pipeline effect of the May 2000 SNA, their 2001 SNA decision would not materially affect the aggregate rate of wages growth. In late October 2001 the ACTU foreshadowed an application to the Commission to increase all award workers’ pay by $25 per week. This claim will be heard at the next Safety Net Review in 2002.

Wage inequality

JCG (2001: Table 4.7) document the long term increase in wage inequality with increases in the decile ratios (D5/D1 and D9/D1) for Australian male and female full-time adult non-managerial weekly earnings over the period 1975–2000 (see also Watts 2001b and references therein). The ratios for the decade 1990–2000 increase more in absolute terms than those for the decade 1980–1990. Wooden (2000: 145) found that there was a marked increase in dispersion after 1994, at a time when enterprise bargaining was accelerating (see also Preston 2001b: 169).

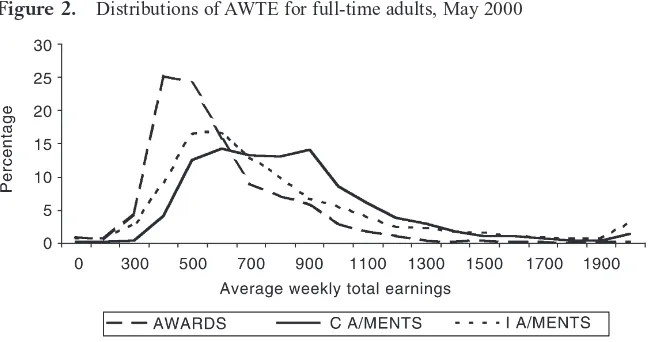

Figure 2 shows the Average Weekly Total Earnings distributions of full-time adult employees in May 2000 under different forms of pay setting (see Carlson et al. 2001). Given the predominance of registered collective agreements as a share of total collective agreements and the high share of individual unregistered agree-ments, Fig. 2 largely represents a comparison of registered collective agreements and unregistered individual agreements. Both distributions are positively skewed. Carlson et al. (2001) find that collective agreements for males and females not only yield higher median and mean wages but also lower Gini ratios than indi-vidual agreements for both total and non-managerial full-time adult employees.

These results do not provide clear insights as to the impact of different methods of pay setting on overall wage inequality. The higher inequality asso-ciated with individual agreements may not translate into an increase in overall inequality, because the distributions overlap. Also we only have a snapshot, so that simple comparisons of wages across different forms of wage setting can be misleading.

Real wage cuts

One outcome of the recent corporate collapses has been the attempt by some companies to impose money wage freezes or even cuts on their employees. Notable examples were at Hewlett-Packard, Qantas, the WA public service and the Kilcoy Pastoral Company.

In mid-year the 1300 employees of Hewlett-Packard Australia along with the remaining 86 000 employees worldwide were given the choice of a 10% pay cut for 4 months, 8 days’ annual leave, a combination of both, a 5% pay cut and 4 days’ vacation, or to do nothing. Few employees accepted a pay cut. Hewlett-Notes: C A/MENTS denotes registered and unregistered collective agreements; I A/MENTS denotes registered and unregistered individual agreements; AWARDS denotes awards only.

Source: Carlson et al. (2001).

Packard had already announced it was sacking 1700 people from its global work-force. Despite the cost savings, another 6000 job cuts were announced.

In October, Qantas wanted to impose a wage freeze for 18 months. Ten unions, representing more than three-quarters of the Qantas workforce, accepted the pay freeze in principle, in an effort to avoid possible job cuts. In mid-November, Qantas announced its plans to cut 2000 jobs. The Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union and Australian Workers’ Union agreed in January 2002 to a 12-month pay freeze through to June 2002, followed by modest pay increases, subject to productivity improvements and cost reductions. The deal was rejected by both Melbourne and Sydney union members, so the dispute remained unre-solved at the time of writing.

State civil servants in Western Australia went on a 24-hour strike in November 2001. Union members wanted the public service benchmark set at the 1995 award rate plus 30%, with 3% adjustments on 1 January 2002 and in 2003. The union alleged that the Government’s proposal of the award plus 22%, with 3% increases for the next three years, effectively amounted to a wage freeze. The Government’s pay proposal aimed to eliminate the different rates of pay within the public service caused by workplace agreements signed by the former Court government (Ellul & Ruse 2001).

In mid-December workers employed at the Kilcoy Pastoral Company abattoir voted in favour of the new work agreement, which entailed longer hours and lower wages, despite the recommendation of the Australian Meat Industry Employees Union to reject the agreement. The meatworks had been closed indef-initely in November following the rejection by employees of an earlier enter-prise agreement. The new agreement has yet to be certified by the Queensland Industrial Relations Commission. The union was to make submissions as to whether the agreement should pass the no-disadvantage test (Green 2001).

In difficult economic circumstances some employers now consider the redesign of pay policies, rather than simple quantity adjustments such as redundancies or a reduced working week, but clearly pay cuts could fail the no-disadvantage test and do not guarantee that quantity adjustments do not also occur. Such initiatives are symptomatic of a shift in the balance of power in industrial relations over the past decade and the declining impact of the award structure (see below).

Union bargaining fees

In February the AIRC approved the charging of a $500 service feeto non-union members by the Electrical Trades Union in exchange for negotiating wage increases. Most unions saw the fee as consistent with the user pays principle and a tool to stimulate flagging membership, particularly with the fee often set above annual union dues, but the fee still allowed non-unionists to contribute to the cost of negotiations. The Federal Government claimed that the levying of bar-gaining fees was against the intention of the Workplace Relations Act.

or not (Corbett 2001). Under the WRA it is illegal to discriminate against a worker on the basis of membership or non-membership of a union. Corbett argues that the non-union member could negotiate either an individual Australian Workplace Agreement or a common-law contract, but the employer may be disinclined to negotiate with members of its workforce under different processes.

Using the Australian Workplace and Industrial Relations Survey 1995 dataset, Wooden (2001b) finds significant union wage differentials across workers from different workplaces, where enterprise agreements prevail. The subsequent spread of enterprise based agreements should have enhanced the benefits of union mem-bership but also should encourage management to try to de-unionise their work-forces (see also ACIRRT 2001: March).

Individual contracts

In mid-January, the Federal Court upheld the right of BHP Iron-Ore to offer its Pilbara workforce individual contracts, ostensibly to raise productivity which was alleged to be impossible if unions were involved. The decision enabled com-panies effectively to outlaw collective bargaining in favour of individual contracts, by refusing to deal with unions (Counsel 2001). In November however, the Western Australian Industrial Relations Commission awarded a 20% pay rise over 12 months to the 500 iron ore workers at BHP (Billiton) who had refused to sign individual contracts and who had had their wages frozen since 1998. The Com-mission was dissatisfied, on grounds of equity, at the operation of two different sets of pay scales after recent improvements to work practices (Norington 2001).3

In May the AIRC ruled that the award was still the appropriate safety net for greenfield sites. This was in response to two mining companies who had argued that classification structures in the awards were inconsistent with those devel-oped through AWAs (Workforce 2001, 1303: 3).

INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS REFORM AND WAGE INFLATION

Under the Accord there were wage targets and coordinating mechanisms which reduced the degree of uncertainty about the macroeconomic wage outcome. Low economy-wide wage inflation contributed to low price inflation and improved international competitiveness. With the increased decentralisation of the wages system, the timing and size of wage increases became less predictable, although award reliant employees remained dependent on centralised wage targets.

Watts (2001a) speculated that the wages system would be put to the test in 2001, with the likelihood of increasing wage demands as a result of the infla-tionary pressures arising from the depreciation of the Australian dollar, the petrol price increase and the introduction of the GST, in the context of a growing economy and relatively low unemployment. As noted, the rate of wage increase has remained relatively stable throughout the year. In this section we explore the factors that could have contributed to the moderate wage growth in 2001.

Institutional and structural change

to increased wage inequality, despite the long boom of the 1990s and the record profit share. This was in stark contrast to the wages breakouts of the 1970s and 1980s, following sustained economic growth.

Fewer than 20% of private sector employees are now unionised. The decen-tralisation of industrial relations which commenced in 1991 was designed explic-itly to quarantine enterprise wage agreements, thereby minimising the flow-on through the network of industrial awards by the tribunals which had characterised previous wage explosions, including the one at the beginning of the 1980s.

In 1997 the Commission rejected an application by the Transport Workers Union for an 11% award wage increase for 35 000 truckers, to bring their pay into line with the rates the union had won from big and medium-sized firms through enterprise bargaining.

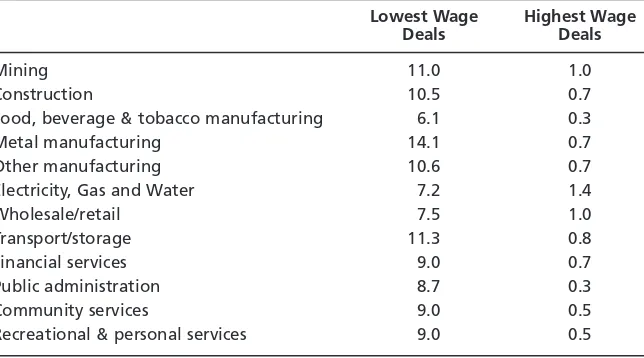

Long notes that, with pay now being set largely at the workplace level, this nexus between the pay of the strong and of the weak has been destroyed. Thus, there is a marked disparity in wage outcomes from enterprise agreements which has led to rising intra-industrial as well as inter-industrial wage inequality, as shown in Table 1, but even greater disparities were reported by ACIRRT in 1999. Watts (2000) also found evidence of rising intra-occupational wage inequality (polarisation) in the male dominated major occupations of Managers and Administrators, Tradespersons and Plant and Machinery Operators over the period 1986–95. In addition, the safety net increases for award reliant employ-242 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS June 2002

Table 1 High and low average annual wage increases (AAWI) in current operating agreements, by industry

Lowest Wage Highest Wage Deals Deals

Mining 11.0 1.0 Construction 10.5 0.7 Food, beverage & tobacco manufacturing 6.1 0.3 Metal manufacturing 14.1 0.7 Other manufacturing 10.6 0.7 Electricity, Gas and Water 7.2 1.4 Wholesale/retail 7.5 1.0 Transport/storage 11.3 0.8 Financial services 9.0 0.7 Public administration 8.7 0.3 Community services 9.0 0.5 Recreational & personal services 9.0 0.5

Note:Current agreements are all agreements that had not reached their stated nominal expiry date at the end of September 2000.

ees have been below the level of average wage increases, with the May 2001 Living Wage Case, for example, yielding 3.25% for workers on the minimum wage. The absence of a relevant and meaningful set of awards facilitates a widening of the intra-occupational and intra-industrial wage distributions.

Non-standard employment has grown as a share of total employment with, for example, annual part-time employment growth of 4.4%, compared to full-time growth of 1.2% between October 1978 and October 2001 (ABS: The Labour Force). A much higher percentage of part-time employees are casual than full-time. Casual employees have less security and lower rates of unionisation and hence less bargaining power. Also increasing numbers of workers are being employed on a contract basis. In responding to competitive pressures, employ-ers have taken the low wage, low productivity option by culling their permanent workforces to cut costs and maximise labour flexibility. Compulsory competitive tendering has reduced labour costs by forcing public sector employees to bid for their jobs against private-sector service providers. In the manufacturing indus-try, tradesperson jobs have been contracted out to labour-hire employees who are required to work more flexibly and do not impose the fixed costs of perma-nent employment. These developments have led to a shift in power in favour of management.4

Long notes that research by the Melbourne Institute reveals that the objec-tive of downsizing appeared to be the implementation of a new business strat-egy to make companies lean and flexible, rather than being a response to falling profits or declining market shares. Prime aged males are most likely to lose jobs, and find it difficult to secure new jobs. Women have secured most of the new jobs in low paid, casual jobs. Finally job insecurity and the prospect of losing entitlements5have also been a factor in the reduction of the growth in wages.

During 2001, there were a number of significant rulings by the Federal and State Tribunals which, while not reversing the shift towards workplace bargain-ing, improved the rights of some marginal groups. These included decisions about the status of casual employees and their access to unpaid leave and the status of subcontractors. Also the granting of generous paid maternity leave provisions to general staff at the Australian Catholic University (ACU) in August 2001 pro-moted an important debate as to whether parental leave provisions should be negotiated workplace by workplace or legislated federally.

CONCLUSION

Despite the presence of inflationary pressures, wage growth was moderate in 2001, but there was evidence of increased inequality. The Federal wages system remains fragmented, even though the incidence of enterprise agreements continued to increase. The attempts of some employers to force workers to accept AWAs was stymied by the AIRC and the Western Australian Tribunal. The structure of awards became less relevant to wage setting with modest increases again granted by the AIRC at the Living Wage Case.

The momentum of labour market reform slowed with the Federal Government attempting to fix up loopholes in some of its regulations, including those relat-ing to unfair dismissal and to small business. Some of their efforts were frus-trated by the Federal political process and through decisions by the AIRC. In addition, the predominance of Labor State Governments frustrated attempts to achieve a unified industrial relations system. Indeed re-regulation of the Victorian and Western Australian systems is occurring.

There is evidence of a profound shift in the balance of power in industrial rela-tions at least at the Federal level, but further research is needed. The outlook for an equitable wage determination process remains pessimistic. The new system with its emphasis on workplace bargaining has yet to be truly tested with sustained full employment.

NOTES

1. Non-farm value added per hour grew 1.31% per annum between 1990 and 1995 and 2.60% between 1996 and 2000 (ABS 2001c). Evidently the faster growth of demand and output in the second half of the decade contributes to the more efficient use of resources and hence more rapid productivity growth.

2. There is an implicit assumption here that individual variations in marginal products require that caution be exercised in award adjustment. A marginal product cannot be viewed as intrin-sic to an individual employee, however, because it reflects both the individual’s personal skills and characteristics, the level of capital investment and the organisational structure of the work-place.

3. A dispute between the FSU and the Commonwealth Bank was resolved in May when four agree-ments were certified in which the CBA was allowed to offer AWAs but individual choice was guaranteed and notice had to be given to the union (Workforce 2001, 1304, May 14: 1). 4. Long also argues that trade liberalisation has imposed a discipline on pay negotiations, due to

import competition.

5. In February 2001, the Federal Employee Entitlements Support scheme had paid just 30% of entitlements lost after the employer went bankrupt (Workforce 2001, 1290: 4)

REFERENCES

ABSThe Labour Force, Cat. no. 6203.0 various issues. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. ABS (2000) Survey of Employee Earnings and Hours, Cat. no. 6306.0, May. Canberra: Australian

Bureau of Statistics.

ABS (2001a) Wage Cost Index, Australia, Cat. no. 6345.0, September. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS (2001b) Average Weekly Earnings States and Australia, Cat. no. 6302.0, August. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS (2001c) National Accounts, Cat. no. 5204.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. ACIRRT (2001) Agreements Database and Monitor (ADAM) Report, various issues. Sydney: Australian

Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training.

AIRC (2001) Safety Net Review—Wages, Australian Industrial Relations Commission, May. http://www.airc.gov.au/my_html/S5000.htm

Apps P (2001) Why an earned tax credit program is a mistake for Australia. The Fred Gruen Lecture Series, Australian National University, May.

Buchanan J, Watson I (2000) The hidden cost of casual work. Canberra Times, 29 November, p.11. Burgess J (1995) Aggregate wage indicators, enterprise bargaining and recent wage increases.

Economic and Labour Relations Review6(2), 216–233.

Carlson E, Mitchell WF, Watts MJ (2001) The impact of new forms of wage setting on wage out-comes in Australia. Paper presented to the Employment Studies Centre Special Conference,

Ten Years of Enterprise Bargaining, May.

Cave M (2001) The coming pay cuts for Australian executives. Australian Financial Review

13 October, 24.

Corbett J (2001) Fee for non-unionists. Newcastle Herald29 May.

Counsel J (2001) BHP court win allows individual contracts. Sydney Morning Herald11 January, 19.

Dawkins P, Freebairn J, Garnaut R, Keating M and Richardson C (1998) How to create more jobs. Letter to the Prime Minister October 26.

DEWRSB (2000) Award and Agreement Coverage Survey. Department of Employment, Workplace Relations and Small Business, July.

DEWRSB (2001) Trends in Enterprise Bargaining. Department of Employment, Workplace Relations and Small Business, September.

Ellul M, Ruse B (2001) Public servants dig in over pay. The West Australian26 October. Golden J (2000) Contracts of Employment, Awards and Agreements. Legal Access Services,

http://www.legalaccess.com.au/news/99081001.shtml

Green G (2001) Staff take leaner cut to save abattoir. Brisbane Courier Mail15 December, 14. Gruen D (2000) Australia’s strong productivity growth; will it be sustained?Reserve Bank of Australia. Inglis D (2001) Earned income tax credits: do they have any role to play in Australia. Australian

Economic Review34(1), 14–32.

JCG (2001) Joint Coalition Governments Submission Safety Net Review—Wages 2000–2001, February.

Long S (2001) The wages of fear and the new workplace. Australian Financial Review21 March, 32.

Mercer Cullen Egan Dell (MCED) (2001) Quarterly Salary Review. Quoted in: Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin November, 65.

Mitchell WF, Muysken J, Watts MJ (2002) Wage and productivity relationships in Australia and the Netherlands. Presented to the AIRAANZ Conference, Queenstown, New Zealand, February.

Moore D (2000) An alternative to the Industrial Relations Commission. Australian Bulletin of Labour

26(2), 128–146.

Norington B. (2001) Iron resolve beats union busters. Sydney Morning Herald6 November, 5. OECD (2001) Quarterly National Accounts, Statistics.

http://www.oecd.org/pdf/M00022000/M00022974.pdf

O’rourke J (2001) PM pushes for an ignited front. Sun Herald2 December, 19.

Preston A (2001a) The Structure and Determinants of Wage Relativities. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Preston A (2001b) The changing Australian labour market: developments during the last decade.

Australian Bulletin of Labour27(3), 153–176.

RBA (2001) Statement of Monetary Policy. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, November. RBA (2002) Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, Statistical Tables, Gross Domestic Product, Table

G9. http://www.rba.gov.au/Statistics/Bulletin/index.html table_g

Waring P, Lewer J (2001) The no disadvantage test: failing workers. Presented at the Employment Studies Centre Conference, Ten Years of Enterprise Bargaining, Newcastle, May.

Watts MJ (2001a) Wages and wage determination in 2000. Journal of Industrial Relations43(2), 177–195.

Watts MJ (2001b) Wage polarisation and unemployment in Australia. In: Mitchell W, Carlson E, eds,Unemployment: The Tip of the Iceberg, pp. 171–92. Sydney: Centre for Applied Economic Research, UNSW.

Wooden M (2000) The Transformation of Australian Industrial Relations. Sydney: The Federation Press.

Wooden M (2001a) Industrial relations reform in Australia: causes, consequences and prospects.

Australian Economic Review34(3), 243–62.

Wooden M (2001b) Union wage effects in the presence of enterprise bargaining. Economic Record

77(236), 1–18.

Workforce (2001) various issues.