www.elsevier.com / locate / bres

Research report

Intra-cerebellar infusion of NMDA receptor antagonist AP5 disrupts

classical eyeblink conditioning in rabbits

a a,b ,

*

Gengxin Chen , Joseph E. Steinmetz

a

Program in Neural Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7007, USA

b

Department of Psychology, Indiana University, 1101 E. 10th Street, Bloomington, IN 47405-7007, USA

Accepted 19 September 2000

Abstract

Rabbits were infused with AP5, an NMDA receptor antagonist, into the region of the cerebellar interpositus nucleus during classical eyeblink conditioning with a tone conditioned stimulus and an air puff unconditioned stimulus. Acquisition of the conditioned eyeblink response was delayed in rabbits infused with AP5 but the NMDA receptor antagonist had little effect on conditioned responses when these same rabbits were infused a second time after reaching asymptotic responding levels. Some rabbits that received AP5 infusions for the first time after the conditioned response was well learned showed temporary alterations in response timing. These data indicate that NMDA receptor activity is involved in the acquisition of classically conditioned eyeblink response and may also be involved in regulating cellular processes involved in response timing and other aspects of conditioned response execution. 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Theme: Neural basis of behavior

Topic: Learning and memory: systems and functions

Keywords: Plasticity; Learning and memory; Interpositus nucleus; Cerebellar cortex; Response timing

1. Introduction early training phase (e.g. see Ref. [8]). Somewhat con-sistent, Caramanos and Shapiro [10] found that systemic It has been well established that the NMDA receptor injections of MK-801, another NMDA antagonist, and plays a critical role in the induction of long-term potentia- intracerebral ventricular infusions of APV impaired spatial tion (LTP) (for review see Refs. [5,16,35]). Administration working memory or reference memory of the radial maze of selective NMDA receptor blockers, such as APV, tasks depending on the drug dose, familiarity with the prevents the induction of LTP but appears to have little environment, and training procedure.

effect on normal synaptic transmission [20,22] (but see Other studies have also suggested that NMDA receptors Refs. [19,44]). In an attempt to associate spatial learning are involved in a variety of learning and memory tasks. with LTP, Morris et al. [34] infused APV into the rat Intra-amygdala infusion of APV blocked the acquisition hippocampus and found that the same drug dose and and consolidation, but not expression of, auditory con-infusion protocol that blocked LTP in vivo also caused ditioned fear-potentiated startle in rats [9,33]. Similarly, impairment of spatial learning in the Morris water-maze. Kim et al. [24] found that ventricular infusions of APV However, their finding is complicated by the observation completely blocked acquisition, but not expression, of that APV may have caused sensorimotor disturbance in the Pavlovian fear conditioning, while the same dose of APV appeared to have no effect on pain sensitivity. Further-more, it has been shown that infusion of APV into the basolateral amygdala also blocked acquisition of con-*Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-812-855-3991; fax: 1

1-812-855-textual Pavlovian fear conditioning [17]. Mathis et al. [30] 4691.

E-mail address: [email protected] (J.E. Steinmetz). showed that post-training ventricular infusion of AP5 and

another competitive NMDA antagonist, gamma-LGLA, part of the memory trace for eyeblink conditioning is impaired the retention of the temporal component but not localized within the cerebellum.

the spatial discrimination component of a Y-maze active It is generally agreed that neurons in the cerebellar deep avoidance task with mice. The involvement of NMDA nuclei express NMDA receptors [1,3,4,45] but whether or receptors has also been demonstrated for step-through not Purkinje cells express NMDA receptors is somewhat inhibitory avoidance tasks [26,29], step-down inhibitory controversial. Expression analysis by in situ hybridization learning [23], discriminative approach response learning has revealed that Purkinje cells express NMDA receptor [7], and taste-potentiated odor conditioning [21]. subunit NR1 but may not express, or express in relatively It has been demonstrated that systemic administration of low levels, the NR2 family subunits [1,45]. However, the non-competitive NMDA antagonist, MK-801 or PCP, pharmacological and electrophysiological studies failed to and the competitive NMDA antagonist, CGP-39551, im- observe functional evidence of NMDA receptors in Pur-paired acquisition of classical eyeblink conditioning in kinje cells [3,4]. These observations may be reconciled if rabbits [37,42] and rats [39]. In all cases, the NMDA one considers that the functional properties of the antagonists appeared to have no effect on retention and heteromeric NMDA receptor-channel complex are critical-performance of previously acquired eyeblink conditioned ly determined by the constituting NR2 subunits.

responses, nor did they appear to affect sensory reactivity In cerebellum, there are cell type-specific expressions of or unconditioned responses. While the above studies did NMDA receptor subunits [1,45]. In adult rats or mice, the not ascertain the target of NMDA antagonists, one study cerebellar granule cells express subunit NR2A and, more showed that memantine, a non-competitive NMDA re- abundantly, NR2C. Deep nuclei express subunit NR2A but ceptor antagonist with higher affinity to cerebellar tissue little NR2C. And, Purkinje cells are thought to express than forebrain tissue, also impaired eyeblink conditioning neither of those subunits. This information combined with in humans [38], suggesting the involvement of cerebellar the gene knockout technique provide some clues of the NMDA receptors. Interestingly, in Robinson’s study [37], functions of NMDA receptors in specific cells. Kishimoto MK-801 appeared to have no effect on conditioning- et al. [27] showed that mutant mice lacking NMDA related potentiation of perforant path-granule cell re- receptor subunit NR2A acquired eyeblink conditioning sponses in hippocampus, suggesting its effective target more slowly than wild-type animals but could attain the might be elsewhere. same asymptotic performance as the wild-type. In contrast, A number of permanent and reversible lesion studies mutants lacking subunit NR2C did not exhibit significant have demonstrated that the cerebellum, especially the impairment. This evidence suggests an important role of interpositus nucleus, is critical for classical eyeblink NMDA receptors in the deep nuclei in the acquisition of conditioning [11,15,28,36,41]. For example, Krupa et al. eyeblink conditioning.

[28] showed that infusion of the GABA agonist muscimolA This study was an attempt to assess the role of cerebellar into the region of the interpositus nucleus abolished NMDA receptors in classical eyeblink conditioning. As in conditioned responses that were established before infu- a number of previous studies, we microinjected AP5 sion. More importantly, muscimol infusion during acquisi- solution into the brain region of interest, i.e. the cere-tion training prevented the formacere-tion of condicere-tioned re- bellum, and examined its effect on the acquisition and sponses and no evidence of learning (i.e. savings) could be performance of conditioned responses. In brief, our data discerned when training was instituted after the infusion. A show that AP5 impaired conditioned response acquisition, recent study by Bracha et al. [6] provided additional and in some animals, had a temporary effect on con-evidence that cellular mechanisms in the cerebellum are ditioned response timing once learning had occurred. Some important for learning the eyeblink conditioned response of these results have been presented elsewhere in prelimin-(CR). Microinjections of anisomycin, a protein synthesis ary form [14].

inhibitor, into the intermediate cerebellum near the inter-positus nuclei impaired the acquisition of the conditioning

and appeared to have no effect on the expression of CRs in 2. Experiment 1: AP5 infusion and acquisition and

well-trained rabbits. In addition, we recently reported that performance of classical eyeblink conditioning

cerebellar protein kinases are important for the acquisition,

pro-cess, and thus behaviorally retard or prevent conditioning. cannula / electrode assembly was cemented into place on Here we used AP5, a specific NMDA receptor antagonist, the skull with dental acrylic along with a bolt for holding which has been widely used in a number of previous the air puff hose and an infrared device that measured

studies. eyelid movement during behavioral training.

2.1. Materials and methods 2.1.3. Behavioral training and drug administration After at least 1 week was allowed for recovery from

2.1.1. Subjects surgery, rabbits received two adaptation sessions (15 min

Fifteen male New Zealand white rabbits (1.6–2.5 kg at and 30 min) while restrained in a Plexiglas box and placed surgery time) were used in experiment 1. Six rabbits were inside a sound-attenuating chamber. From the third day on, assigned to an AP5 group. Nine rabbits were initially rabbits received one session of standard delay conditioning assigned to a saline control group with six eventually per day. During the training, a 350 ms, 85 dB SPL, 1 kHz included in subsequent data analyses. Before the experi- tone was used as the conditioned stimulus (CS), and a 100 ment and between the training sessions, the rabbits were ms, 3 psi co-terminating air puff was used as the un-individually housed in cages and provided ad lib access to conditioned stimulus (US). The tone CS was delivered via food and water. A 12 / 12 h light / dark cycle was main- a speaker mounted|30 cm above the rabbit. The air puff tained in the animal housing area. US was delivered via a 3-mm air nozzle positioned 1 cm from the middle of the rabbit’s eye. Movement of the

2.1.2. Surgery external eyelids was measured as the unconditioned

re-Surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions. sponse (UR) and the conditioned response (CR) using an Rabbits were deeply anesthetized with injections of 6 infrared emitter / detector located 4–5 mm in front of the mg / kg xylazine and 60 mg / kg ketamine, and maintained rabbit’s cornea that measured changes in diffraction of a throughout the surgery with intramuscular injections of a beam of infrared light [43]. These measured changes were mixture of xylazine (3 mg / kg) and ketamine (30 mg / kg) amplified to reflect millimeters of external eyelid closure in delivered every 45 min. During the surgery, the skull over response to the CS or the US. Movement of the external the cerebellum was removed and a cannula–electrode eyelids was not restricted by eyelid clips during training. assembly was implanted into the region between the Each session consisted of six blocks of 10 trials (one interpositus nucleus and dentate nucleus. The cannula was CS-alone test trial and nine CS–US paired trials). The constructed from 22 gauge stainless steel tubing. An inter-trial interval (ITI) varied pseudorandomly from 20 to epoxy-insulated, 00 stainless steel electrode (|1 MV 30 s with an average of 25 s.

impedance) was glued to the cannula with its tip located All rabbits in the saline and AP5 groups were trained for about 1.5 mm lower than the cannula tip. The skull was 20 sessions of standard delay conditioning, with drug positioned so that lambda was 1.5 mm below bregma. The treatment given as shown in Table 1. The first period of electrode tips were stereotaxically implanted at 5.3 mm injections in phase 1 (sessions 1–5) was designed to lateral from midline and a maximum of 14.5 mm below examine the effect of AP5 or saline infusion on the lambda (depending on the observation of characteristic acquisition of eyeblink conditioning. Phase 2 of training interpositus nucleus activity recorded from the electrode (sessions 6–10) allowed us to examine post-injection when it was lowered). The anterior–posterior coordinate performance before rabbits reached asymptotic perform-referenced to lambda was calculated with an equation: 4.8 ance. We then examined the asymptotic performance in mm20.31 mm3D, where D was the distance measured phase 3 (sessions 11–15). The second period of injections between bregma and lambda (with posterior positive, in phase 4 (sessions 16–20) tested the effects of AP5 or anterior negative). This correction formula was created saline infusion on the performance of well-learned re-using regression analyses involving previous interpositus sponses.

nucleus recording and lesion data (e.g. Ref. [13]). A DL-AP5 solution (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was stainless steel stylet was inserted into the cannula after dissolved in sterile physiological saline to a concentration surgery and was replaced between sessions to prevent the of 2.5 mg /ml and the pH of the solution was adjusted to cannula from clogging. After the hole in the skull sur- about 7.0 with NaOH. During each infusion session, a 26 rounding the cannula was filled with bone wax, the gauge needle was inserted into the guide cannula with its

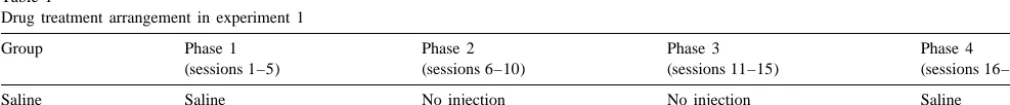

Table 1

Drug treatment arrangement in experiment 1

Group Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4

(sessions 1–5) (sessions 6–10) (sessions 11–15) (sessions 16–20)

Saline Saline No injection No injection Saline

tip positioned 0.75 mm below the cannula tip. Using an 2.2. Results infusion pump, each rabbit received 2-ml injections at a

rate of 8 ml / h (total duration 15 min) via a Teflon tube Twelve of the 15 rabbits met our criteria for inclusion in connected to a 10-ml Hamilton syringe. The training the study and their data were analyzed. Three rabbits in the procedure started about 5 min after the infusion began to saline group were excluded; one did not reach the 75% CR allow the infusate to diffuse. criteria, another failed to pass the muscimol test, and a third one learned very slowly. Although the third rabbit reached the 75% CR rate criteria on the last day of 2.1.4. Histology and implant location verification training, histology showed a partial lesion to the inter-After completing all the training sessions, rabbits were positus nucleus due to the cannula placement. Therefore, returned to the conditioning chamber for one additional six AP5 rabbits and six saline rabbits were included in the session during which they were infused with 2 ml of the statistical analyses.

GABA agonist, muscimol (Sigma Chemical, dissolved inA

saline to 400 ng /ml), to verify the effectiveness of the

2.2.1. Histology implant. The muscimol was infused via the pump 15 min

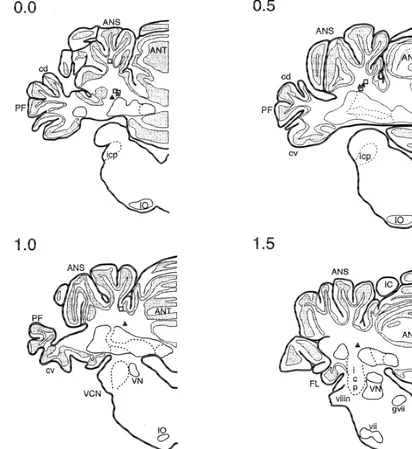

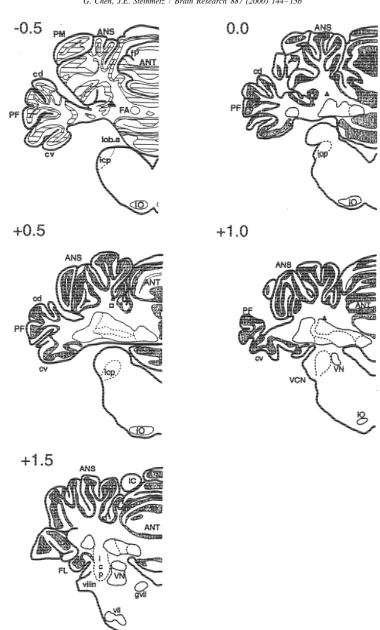

Fig. 1 depicts the cannula tip placements of all rabbits before the test session. A series of paired CS–US trials

included in the analysis. Most cannula placements were were then delivered and the effects of muscimol on

immediately dorsal to the area of the interpositus nucleus conditioned responding were noted. If muscimol did not

identified in past studies as critical for eyeblink con-effectively reduce the CR rate of a rabbit to less than 10%

ditioning (e.g. Refs. [32,41]). A few placements were CRs on two consecutive blocks of training, that rabbit was

somewhat distal from the interpositus nucleus, but the excluded from future data analysis as we assumed that

muscimol test indicated that the drug was still able to failing this test indicated that the cannula was not

diffuse to the critical area. While some gliosis was positioned correctly in the interpositus nucleus.

observed around the cannula and electrode tips in some When this test was completed, the rabbits were

over-rabbits, when the tissue was examined under a light dosed with an i.v. injection of 150 mg / kg pentobarbitol

microscope, cell bodies were clearly seen in the area of the and perfused intra-aortically with 0.9% saline followed by

left interpositus and dentate nucleus, and the tissue did not 10% formalin. The brains were then removed and fixed in

differ from the other side of the cerebellum. Cell bodies 30% sucrose / 10% formalin solution. After a week, the

could be clearly seen just beneath the cannula tips sug-brains were embedded, frozen sectioned at a thickness of

gesting that the infusion did not cause neuronal death. 40 mm, and stained with cresyl violet. Cannula locations

Because it was hard to identify lesions caused by cannula and the conditions of neurons in the interpositus nuclei

and electrode implant solely with microscopic histology, were examined under a light microscope.

the behavioral criteria described above were also used to exclude animals with lesions caused by cannula placement or volume injection.

2.1.5. Data analysis

For the rabbit excluded from statistical analysis because Session-wide averages of behavioral response

parame-of failing the muscimol test, the cannula placement was ters, including percent CRs, CR amplitudes, latencies to

found to be too posterior and somewhat high. In rabbits response onset and peak, and UR amplitudes were

ana-that did not reach the 75% CR criteria, either the cannula lyzed with mixed-design ANOVAs. In these analyses,

tip touched the dorsolateral region of the interpositus group (AP5 or control) was the between factor and session

nucleus or the electrode went through it, causing notice-(1–20) was the repeated measure on subjects. Behavioral

able damage to the nucleus. responses on the CS-alone test trials and CS–US paired

trials were analyzed separately. Rabbits that did not reach

75% CRs on any of the 20 sessions were excluded from 2.2.2. Behavioral analyses

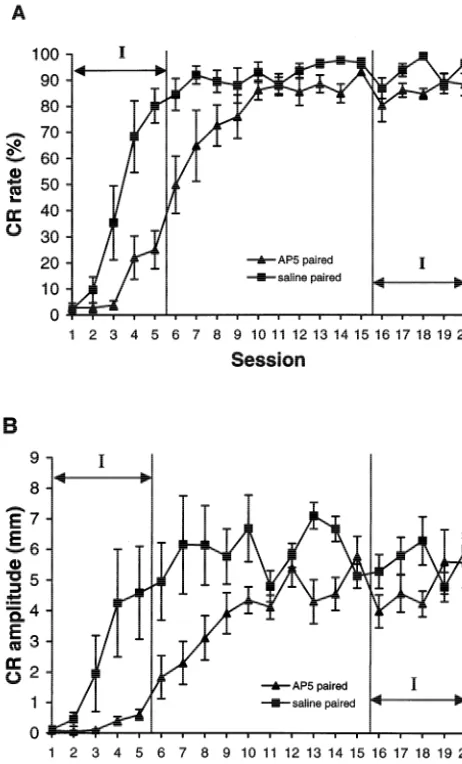

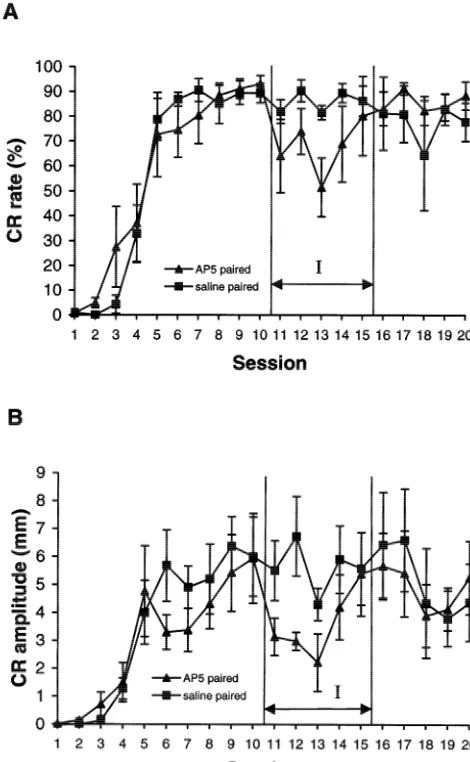

statistical analysis as there was a possibility that those Fig. 2 shows the learning curves of the AP5 and saline rabbits sustained damage to the interpositus nucleus due to groups over the 20 training sessions. The data from CS– the cannula and recording electrode that were implanted. US paired trials and CS-alone trials were analyzed separ-Rabbits that showed no reductions in CRs after muscimol ately.

infusion were also excluded because the cannulas were likely misplaced.

Next, to examine the drug effects on CR characteristics, 2.2.2.1. Phase 1 (sessions 1 –5). Phase 1 represented the individual CRs on CS-alone trials were gathered and five initial drug treatment days. For analysis purposes, analyzed. Conditioned responses with onset latency shorter these sessions provide a good sample of acquisition than 50 ms were considered as artifacts and thus excluded. training. Because very few CRs were present in the AP5 or Mixed-design ANOVAs were performed to compare the the saline rabbits on sessions 1 and 2, two ANOVAs were

Fig. 1. Schematics of coronal sections through the rabbit cerebellum and brainstem showing locations of cannula tips for experiment 1 rabbits. Numbers represent distance in millimeters of the section relative to the lambda skull landmark. Squares depict cannula tips for saline control rabbits and triangles depict cannula tips for AP5 rabbits. ANS, ansiform lobe; ANT, anterior lobe; IC, inferior colliculus; icp, inferior cerebellar peduncle; IO, inferior olive; PF, paraflocculus lobe; VCN, ventral cochlear nucleus; VN, vestibular nucleus.

session 1 and 2 data and one analysis on sessions 3 to 5 in the AP5 group (see Fig. 2A). Next, the CR amplitudes

data. of the AP5 group were significantly smaller than the saline

No group or session effects were found on any of the controls (F(1,10)55.03, P,0.05) (see Fig. 2B). In con-measures taken when session 1 and 2 data were analyzed. trast, there was no difference in UR amplitudes between This was expected because very few CRs were displayed the two groups, suggesting that the drug treatments had no by either group of animals on these days. Analyses of the effect on general motor responses. Significant session data from sessions 3 to 5, however, revealed significant effects were noted for all variables analyzed thus indicat-difference between groups. Firstly, analysis of percent CRs ing that learning was taking place (all Ps,0.01).

showed that the AP5 group produced significantly fewer Analysis of onset latencies revealed that the AP5 rabbits CRs than the saline group on each day (F(1,10)513.91, had significantly longer response onset latencies (M5257

though AP5 infusions were discontinued after session 5 (see Fig. 2). Compared to control rabbits, AP5 rabbits still had significantly lower percentage CRs (F(1,10)55.44,

P,0.05) and lower CR amplitudes (F(1,10)55.38, P, 0.05). The AP5 rabbits also displayed significantly longer CR onset latencies (F(1,10)58.75, P,0.015) during phase 2; the mean onset latencies for the AP5 and saline rabbits were 210 ms and 157 ms, respectively. Additional acquisi-tion occurred in both groups, however, as significant session effects were noted for percentage CRs, CR am-plitudes and onset latencies (all Ps,0.001). No differences between UR amplitudes were observed, however.

2.2.2.3. Phase 3 (sessions 11 –15). Based on a number of previous studies, we expected that the rabbits would reach asymptotic performance levels by sessions 11 to 15. Results of ANOVAs conducted on the percent CR data showed, however, that the AP5 group generated fewer CRs than the saline group (F(1,10)58.03, P,0.05), although the relative difference in the group averages (saline vs. AP5 as 94.4% vs. 87.9%) was much smaller than that in phase 1 (see Fig. 2A). The analysis also revealed that the CR amplitudes of the AP5 group were significantly smaller than the saline controls (F(1,10)512.25, P,0.001) and that the AP5 rabbits (M5172 ms) had significantly longer response onset latencies than the saline control (M5143 ms) (F(1,10)59.69, P,0.05). These results indicate that the impairment of conditioning seen in AP5 rabbits lasted well into training when no AP5 was delivered. That is, there appears to be a lack of a savings effect in the AP5 rabbits once infusion of the NMDA antagonist was dis-continued. Again, there was no difference in UR am-plitudes between the two groups.

Fig. 2. Learning curves for rabbits trained across 20 sessions in experi-ment 1. (A) Percent CRs and (B) CR amplitudes recorded from saline

2.2.2.4. Phase 4 (sessions 16 –20). We expected that by (squares) and AP5 (triangles) rabbits. Sessions during which drug

sessions 16–20, all rabbits would have most certainly infusions occurred are indicated by the I-labeled arrows. Error bars5

reached asymptotic responding levels and that this would S.E.M.

be a good time to test the effects of AP5 on well-learned CRs. Analysis of the sessions factor showed few changes in responding between session 16 and session 20 as

P,0.05). It should be noted, however, that in calculating significant session effects were not observed when per-the measures for each session, when a CR was absent, per-the centage CRs, CR amplitudes or CR onset latencies were CR amplitude was assigned zero and the onset latency was analyzed. However, analysis of phase 4 training data assigned a default value of 500 ms (i.e. the end of the suggest that the AP5 rabbits reached slightly lower asymp-trial). The smaller average CR amplitudes of the AP5- totic responding levels: the AP5 rabbits showed a sig-treated animals and the longer average onset latencies nificantly lower percentage CR [F(1,10)58.01, P,0.05] could therefore be due to fewer CRs being executed by and longer onset latencies [F(1,10)57.82, P,0.05] than these rabbits as well as a prolonged acquisition during control rabbits. The mean onset latency for the AP5 rabbits which lower amplitude and later responses were executed. was 185 ms while the mean onset latency for the control To address this issue, additional analyses on the CRs rabbits was 149 ms. No differences in CR or UR am-observed during CS-alone trials are described below. plitudes were found.

CS-alone trials were analyzed. These responses were not many sessions after AP5 infusion. This suggests that contaminated by the presence of URs and data analyses blocking NMDA receptors disrupted critical cellular plas-included only trials on which CRs were executed. ticity mechanisms that were responsible for establishing During sessions 3 to 5 of phase 1 of training, the AP5 eyeblink CRs. When the rabbits were trained to asymptotic group showed significantly fewer CRs than saline control performance levels and AP5 was infused a second time, group (F(1,10)57.07, P,0.05). The AP5 rabbits also had the NMDA antagonist appeared to have a somewhat lesser, longer onset latencies than the control group (Ms5408 ms but nonetheless significant, effect on CR characteristics. versus 289 ms) (F(1,10)511.88, P,0.01). Similarly, there These data suggest that activity at NMDA receptors in the was also a significant difference between group means cerebellum may be important for the initial establishment (352 ms versus 283 ms for the AP5 and control rabbits, and subsequent maintenance or performance of well-respectively) when CR peak latencies were computed learned classically conditioned eyeblink responses. (F(1,10)516.33, P,0.005). However, analyses did not

reveal statistical difference in CR amplitudes between the

groups. These results are in agreement with data from 3. Experiment 2. Further verification of the effect of

paired trials that showed that AP5 rabbits had significantly AP5 on retention of eyeblink CRs

longer response latencies than the saline control thus

suggesting that early in training, infusion of the NMDA In experiment 1, infusion of AP5 into the cerebellum antagonist influenced response timing as well as the was found to impair the acquisition of classical eyeblink number of CRs executed. conditioning in rabbits. And, the same infusion procedures Analysis of CS-alone trials during phase 2 of training appeared to have much lesser effects on the retention or (sessions 6–10) revealed significantly longer onset laten- expression of the conditioned responses in well-trained cies for AP5-infused rabbits (M5242 ms) compared to animals. However, in experiment 1, AP5 retention tests control rabbits (M5180 ms) (F(1,10)56.59, P,0.025), were conducted on the same rabbits that received AP5 however significant peak latency, percent CRs, and CR treatment during the first 5 days of the acquisition period. amplitude differences were not observed. It is possible that compensation mechanisms might have Significant differences in onset latencies (Ms5216 ms developed in these animals such that they were immune and 175 ms for AP5 and control rabbits, respectively) and from the later action of AP5. Experiment 2 was performed peak latencies (Ms5260 ms and 291 ms for AP5 and to verify the effect of AP5 on the retention of eyeblink control rabbits, respectively), and CR amplitude were conditioning. In this experiment, two groups of rabbits observed in phase 3 of training (sessions 11–15) were trained until CRs were well-established then treated (F(1,10)511.38, P,0.01, F(1,10)59.43, P,0.05, and with either saline or AP5 and CR performance was

F(1,10)517.52, P,0.005 for onset latency, peak latency compared. and CR amplitude, respectively). No significant difference

in percentage CRs was found.

3.1. Materials and methods During phase 4 of training (sessions 16–20), although

significant differences between the AP5 and control rabbits

were not found when percentage CRs and CR amplitudes 3.1.1. Subjects and surgery

were analyzed, differences were noted when response Fourteen male rabbits of the same type and maintained latencies were examined. The AP5 rabbits displayed longer in the same condition as those included in experiment 1 onset latencies (Ms5211 ms versus 167 ms) (F(1,10)5 were used in this experiment. Of these, based on the 6.78, P,0.05) and longer peak latencies (Ms5248 ms inclusion criteria that were described for experiment 1, versus 279 ms) (F(1,10)55.63, P,0.05) than control nine were eventually included in the data analyses.

Sub-rabbits. jects were housed, fed and surgically prepared as described

Overall, analysis of the characteristics of CRs displayed in experiment 1. on CS-alone trials indicated that the effects of NMDA

antagonist infusion during early sessions of paired CS–US

training had somewhat long-lasting effects on CR per- 3.1.2. Behavioral training, drug administration and formance. Differences between AP5 rabbits and saline histology

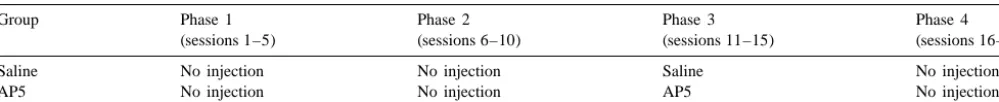

Table 2

Drug treatment arrangement in experiment 2

Group Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4

(sessions 1–5) (sessions 6–10) (sessions 11–15) (sessions 16–20)

Saline No injection No injection Saline No injection

AP5 No injection No injection AP5 No injection

3.2. Results indicating that for the most part, all rabbits had reached

asymptotic responding levels by session 10 (see Fig. 4). Five rabbits were excluded in this experiment because

they did not reach the 75% CR criteria. Three of them gave 3.2.2.3. Phase 3 (sessions 11 –15). During the drug infu-no more than 10% of CRs in the first 10 sessions and thus sion sessions (session 11 to session 15), no significant were excluded immediately before the injection sessions. differences between the groups on any measures were Hence, four rabbits were included in the saline group and found with ANOVA although the learning curves (Fig. 4) five rabbits were included in the AP5 group. appear to show that the AP5 group had some temporary decrements in both percent CRs and CR amplitudes. The

3.2.1. Histology ANOVAs did indicate a significant session effect in onset

Fig. 3 illustrates the cannula tip placements of all rabbits latencies (F(4,28)52.85, P,0.05) and a trend of session included in the analyses for experiment 2. As in experi- effect in CR amplitudes (F(4,28)52.18, P,0.1). Mean ment 1, in the left (infusion) side of the cerebellum, cell onset latencies for the AP5 and control groups were 201 bodies were clearly seen under light microscope in the area and 180 ms, respectively. Examination of the phase 3 data of interpositus and dentate nucleus. The number of cells of individual rabbits revealed that the lower percent CRs, observed did not appear to be different from the other side smaller CR amplitudes and longer onset latencies were of the cerebellum. Limited gliosis was observed around the present in only two of the five AP5 rabbits. The other three cannula and / or electrode tips in some of the rabbits, but rabbits showed little or no effect of the AP5 infusion. The the nuclei appeared to be intact. temporary effect on CR performance seemed not to be In the rabbits that did not reach the 75% CR criterion, related to the relative placement of the infusion; one rabbit the electrode tips penetrated into either the interpositus or had a cannula placement just dorsal to the interpositus the dentate nucleus and caused clear damage. Thus, it is nucleus while the second rabbit had a cannula placement likely that poor learning was due to cerebellar damage just beneath the cerebellar cortex. It should be noted that caused by the implantation of the cannulae. all five rabbits showed abolition of responding when muscimol was infused after training thus indicating that all 3.2.2. Behavioral analyses cannula placements were effective in delivering the AP5 to Fig. 4 illustrates the learning curves of the two groups the critical region of the interpositus nucleus known to be over the 20 training sessions that were given. As in involved in eyeblink conditioning. Alternatively, previous experiment 1, the averages of CS–US paired trials and research has suggested that inactivation of select regions of CS-alone trials were analyzed separately. To be consistent cerebellar cortex significantly affects CR performance. For and to allow for cross-experiment comparisons, the same example, Attwell et al. [2] demonstrated that reversible phases of sessions were examined with ANOVAs as in inactivation of cerebellar cortex with CNQX, which

experiment 1. blocked cortical AMPA-kainate receptors, effectively

blocked the performance of previously established CRs. 3.2.2.1. Phase 1 (sessions 1 –5). ANOVAs conducted on

data collected during sessions 1 and 2 and sessions 3 to 5 3.2.2.4. Phase 4 (sessions 16 –20). During the last five revealed no significant differences between groups on any no-injection sessions (session 16 to session 20), no group measures. As expected, there was a strong session effect effects were revealed and no consistent session effects in (P,0.0001) for sessions 3 to 5 involving all measures the data were noted (see Fig. 4).

except UR amplitude, indicating a solid CR acquisition

trained to asymptotic performance levels, infusions of AP5 appeared to have a temporary effect on CR production and topography in some rabbits. These data are, for the most part, in agreement with the results of experiment 1 that suggest that the NMDA antagonist consistently affects acquisition and has a transitory effect on the timing of classically conditioned eyeblink responses.

4. Discussion

The primary findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) intracerebellar infusion of AP5, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist, during training impaired the acquisition of classical eyeblink conditioning in rabbits. (2) NMDA receptor antagonist effects on conditioning were still apparent several days after AP5 infusion sug-gesting that AP5 may have blocked critical cellular pro-cesses responsible for neuronal plasticity that underlies CR acquisition. (3) Administration of AP5 to well-trained rabbits produced an effect on CR performance in a subset of rabbits given the NMDA antagonist when asymptotic responding levels were reached.

An important issue addressed with the present data is whether the AP5 infusions acted on the learning process during early phases of acquisition training, or merely affected the performance or expression of the CRs during learning. Two basic lines of evidence in our data suggest that the effects of AP5 during acquisition period were on the learning process, per se, and not restricted to CR performance. Firstly, when the drug treatments stopped after Session 5, the drug-treated animals did not immedi-ately perform as well as the saline animals. Instead, their Fig. 4. Learning curves for rabbits trained across 20 sessions in

experi-performance gradually improved over the next few ses-ment 2. (A) Percent CRs and (B) CR amplitudes recorded from saline

sions (see Fig. 2). In fact, a statistical difference in percent (squares) and AP5 (triangles) rabbits. Sessions during which drug

infusions occurred are indicated by the I-labeled arrow. Error bars5 CRs between the AP5 and control rabbits was still present

S.E.M. during sessions 11 to 15 indicating a reduced savings of

learning effect during the post-infusion training period. lyzed. The AP5 rabbits showed longer peak latencies Secondly, when AP5 was injected into well-trained ani-(M5285 ms) (F(1,7)56.49, P,0.05) than did control mals that were exposed previously to AP5, their CR rabbits (M5232 ms). As was the case for paired trials, two performances were generally not affected (experiment 1). of the five rabbits showed relatively large changes in CR Although two rabbits from experiment 2 showed a pro-characteristics whereas the remaining three rabbits showed nounced decrement in percent CRs and CR amplitudes on slight, if any, changes. Taken together, the results of these paired trials when AP5 was infused for the first time after CS-alone analyses may provide an explanation for the asymptotic responding was reached, analyses of CS-alone temporary decrement in percent CRs observed during AP5 trial data showed that these deficits may be attributable to infusion on sessions 11–15. It appears that the AP5 caused delayed CR onsets. The data strongly suggest that, at most, a temporary impairment in the performance of the CR, i.e. a temporary effect on CR performance occurs in some on some trials, a subset of the AP5 rabbits were executing well-trained rabbits infused with AP5 for the first time. relatively late conditioned responses (as indicated by However, the potential contribution of a performance significantly longer CR peak latencies) that may have been deficit in producing the slow acquisition noted in Experi-obscured by the UR present on many of the paired trials ment 1 cannot be unequivocally excluded by the present

delivered in these sessions. data.

restricted to the interpositus nucleus or spread to the NMDA receptor activity during paired presentations of the overlying cerebellar cortex. A comparison with a previous CS and US late in each daily training session. In addition, study by Krupa et al. [28] might shed some light on this it is possible that NMDA receptor activity is important for point. In their study with labeled muscimol, Krupa et al. only a portion of the critical cellular processes involved in showed that the drug diffusion area included the inter- CR acquisition.

positus nucleus and portions of the overlying cortex. They Our present results are in agreement with previous observed no labeling outside of the cerebellum. Our studies involving systemic administration of NMDA re-cannula placements were very similar to those of Krupa et ceptor antagonists [37–39,42], that is, blocking NMDA al. While we injected a larger volume, it was injected at a receptors impaired the acquisition of classical eyeblink slower rate. We thus expect that our drugs diffused into conditioning. Indeed, our results may help to explain the similar areas as the Krupa et al. study. Given the extent of seemingly contradictory results reported by Robinson [37] spread that we suspected to have occurred, it seems likely that systemic infusion of MK-801 retarded acquisition of that the AP5 affected the interpositus nucleus and also at the eyeblink CR but did not affect perforant path–granule least the ventral portion of cerebellar cortex. Thus, the site cell excitability. If one assumes that a major target of the of action of the NMDA-receptor antagonist could have effects of NMDA blockers is the cerebellum, and not the been in the cerebellar cortex, the deep cerebellar nuclei, or hippocampal formation, one would expect the results

in both regions. observed in the present study and by Robinson [37]. There

Interestingly, some recent models of the involvement of is one discrepancy between our data and the data of the cerebellum in eyeblink conditioning have suggested Robinson [37] and Thompson and Disterhoft [42] — these that critical learning-related plasticity occurs in both studies did not report alternations in CR timing after drug cerebellar cortex and the interpositus nucleus (e.g. Refs. injection for delay conditioning. By contrast, our data from [12,25,31,40]). In these models, excitability changes at the experiments 1 and 2 showed some alteration in CR timing level of the interpositus nucleus have been suggested to be in AP5-treated animals. One obvious difference between important for providing drive on brainstem motor neurons the present studies and the previous studies is the respec-responsible for CR execution while excitability changes in tive routes of administration of the NMDA antagonists. cerebellar cortical areas have been suggested to be im- Infusing NMDA receptor antagonists directly into the portant for response timing, amplitude gain and, perhaps, cerebellum may produce stronger NMDA receptor an-regulation of plasticity in the deep cerebellar nuclei. Given tagonism in areas of the cerebellum critical for response the range of locations of infusions sites used in the present timing than when the antagonists are by systemic adminis-experiments (see Figs. 1 and 3), it seems likely that the tration. It is also possible that systemic administration of pattern of NMDA receptor antagonist infusions differed NMDA receptor antagonists may produce effects on across rabbits thus producing varying levels of effects in multiple brain sites such that the overall effects are cerebellar cortex and the deep nuclei. For example, it is different than local administration effects observed in our possible that the temporary CR timing deficits noted in the study. And, we cannot rule out that AP5 may have side two rabbits from experiment 2 were due to AP5 effects on effects other than blocking NMDA receptor (see Ref. [44]). timing mechanisms that are generated by activity in areas It would be interesting to repeat our experiment with other of cerebellar cortex (i.e. AP5 infusions affected predomi- NMDA receptor antagonists, such as MK-801 or PCP, to nantly cortical areas). Further studies involving varying examine their effects on the eyeblink conditioning. amounts of AP5 placed at a variety of locations within In summary, the present data indicate that NMDA cerebellar cortex and the deep nuclei would provide receptor activities within the cerebellum are involved in additional information concerning the learning-related the learning of classical eyeblink conditioning in rabbits. processes that are dependent on NMDA receptor activity. This finding is consistent with a number of previous It should also be noted that AP5 does not completely studies that have demonstrated an involvement of NMDA block acquisition of the eyeblink CR as does muscimol receptors in learning and neural plasticity. The finding also infusion [28] or permanent lesion techniques (e.g. Refs. supports the hypothesis that at least part of the memory [32,41]). We observed a similar effect in a previous study trace for the learned response for this paradigm is located when a H7, a protein kinase inhibitor, was infused into the within the cerebellum. This observation is compatible with region of the deep cerebellar nuclei [13]. There are several a host of other lesion and recording experiments implicat-possible reasons why a complete blockade of learning was ing a critical role for the cerebellum in the learning and not observed. For example, while our muscimol test memory of this simple conditioned response.

revealed that the cannula were placed in locations that affected performance of the eyeblink CR, we cannot be

certain that the diffusion of the amount of AP5 that we Acknowledgements

infused affected the targeted region as effectively as the

classical conditioned behavior, Behav. Neurosci. 106 (1992) 879– J.E.S. This research formed a portion of the Ph.D.

disserta-888. tion written by G.C. who is currently a Research Scientist

[16] Y. Dudai, The Neurobiology of Memory, Oxford University Press, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, 1989.

New York. [17] M.S. Fanselow, J.J. Kim, Acquisition of contextual Pavlovian fear conditioning is blocked by application of an NMDA receptor antagonist D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid to the basolateral amygdala, Behav. Neurosci. 108 (1994) 210–212.

[18] H. Gomi, W. Sun, C.E. Finch, S. Itohara, K. Yoshimi, R.F.

References Thompson, Learning induces a CDC2-related protein kinase,

KKIAMRE, J. Neurosci. 19 (1999) 9530–9537.

[19] J.J. Hablitz, I.A. Langmoen, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antago-[1] C. Akazawa, R. Shigemoto, Y. Bessho, S. Nakanishi, N. Mizuno,

nists reduce synaptic excitation in the hippocampus, J. Neurosci. 6 Differential expression of five N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit

(1986) 102–106. mRNAs in the cerebellum of developing and adult rats, J. Comp.

[20] E.W. Harris, A.H. Ganong, C.W. Cotman, Long-term potentiation in Neurol. 347 (1994) 150–160.

the hippocampus involves activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate re-[2] P.J.E. Attwell, S. Rahman, M. Ivarsson, C.H. Yeo, Cerebellar

ceptors, Brain Res. 323 (1984) 132–137. cortical AMPA-kainate receptor blockade prevents performance of

[21] T. Hatfield, M. Gallagher, Taste-potentiated odor conditioning: classically conditioned nictitating membrane responses, J. Neurosci.

impairment produced by infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate re-19 (RC45) (re-1999) 1–6.

ceptor antagonist into basolateral amygdala, Behav. Neurosci. 109 [3] E. Audinat, B.H. Gahwiler, T. Knopfel, Excitatory synaptic

po-(1995) 663–668. tentials in neurons of the deep nuclei in olivo-cerebellar slice

[22] C.E. Herron, R.A. Lester, E.J. Coan, G.L. Collingridge, Frequency-cultures, Neuroscience 49 (1992) 903–911.

dependent involvement of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus: a [4] E. Audinat, T. Knopfel, B.H. Gahwiler, Responses to excitatory

novel synaptic mechanism, Nature 322 (1986) 265–268. amino acids of Purkinje cells and neurones of the deep nuclei in

[23] D. Jerusalinsky, M.B.C. Ferreira, R. Walz, R.C. Da Silva, M. cerebellar slice cultures, J. Physiol. 430 (1990) 297–313. Bianchin, A.C. Ruschel, M.S. Zanatta, J.H. Medina, I. Izquierdo, [5] T.V.P. Bliss, G.L. Collingridge, A synaptic model of memory: Amnesia by post-training infusion of glutamate receptor antagonists long-term potentiation in the hippocampus, Nature 361 (1993) into the amygdala, hippocampus, and entorhinal cortex, Behav.

31–39. Neural Biol. 58 (1992) 76–80.

[6] V. Bracha, K.B. Irwin, M.L. Webster, D.A. Wunderlich, M.K. [24] J.J. Kim, J.P. DeCola, J. Landeira-Fernandez, M.S. Fanselow, N-Stachowiak, J.R. Bloedel, Microinjections of anisomycin into the methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist APV blocks acquisition but intermediate cerebellum during learning affect the acquisition of not expression of fear conditioning, Behav. Neurosci. 105 (1991) classically conditioned responses in the rabbit, Brain Res. 788 126–133.

(1998) 169–178. [25] J.J. Kim, R.F. Thompson, Cerebellar circuits and synaptic mecha-[7] L.H. Burns, B.J. Everitt, T.W. Robbins, Intra-amygdala infusion of nisms involved in classical eyeblink conditioning, Trends Neurosci.

the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist AP5 impairs acquisi- 20 (1997) 177–181.

tion but not performance of discriminated approach to an appetitive [26] M. Kim, J.L. McGaugh, Effects of intra-amygdala injections of CS, Behav. Neurol. Biol. 61 (1994) 242–250. NMDA receptor antagonists on acquisition and retention of inhib-[8] D.P. Cain, D. Saucier, J. Hall, E.L. Hargreaves, F. Boon, Detailed itory avoidance, Brain Res. 585 (1992) 35–48.

behavioral analysis of water maze acquisition under APV or CNQX: [27] Y. Kishimoto, S. Kawahara, Y. Kirino, H. Kadotani, Y. Nakamura, contribution of sensorimotor disturbances to drug-induced acquisi- M. Ikeda, T. Yoshioka, Conditioned eyeblink response is impaired in tion deficits, Behav. Neurosci. 110 (1996) 86–102. mutant mice lacking NMDA receptor subunit NR2A, NeuroReport 8 [9] S. Campeau, M.J.D. Miserendino, M. Davis, Intra-amygdala infu- (1997) 3717–3721.

sion of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist AP5 blocks [28] D.J. Krupa, J.K. Thompson, R.F. Thompson, Localization of a acquisition but not expression of fear-potentiated startle to an memory trace in the mammalian brain, Science 260 (1993) 989– auditory conditioned stimulus, Behav. Neurosci. 106 (1992) 569– 991.

574. [29] K.C. Liang, W. Hon, M. Davis, Pre- and post-training infusion of [10] Z. Caramanos, M.L. Shapiro, Spatial memory and N-methyl-D- N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists into the amygdala impair aspartate receptor antagonists APV and MK-801: memory impair- memory in an inhibitory avoidance task, Behav. Neurosci. 108 ments depends on familiarity with the environment, drug dose, and (1994) 241–253.

training duration, Behav. Neurosci. 108 (1994) 30–43. [30] C. Mathis, J. de Barry, A. Ungerer, Memory deficits induced by [11] P.F. Chapman, J.E. Steinmetz, L.L. Sears, R.F. Thompson, Effects g-L-glutamyl-L-aspartate and D-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate in a of lidocaine injection in the interpositus nucleus and red nucleus on Y-maze avoidance task: relationship to NMDA receptor antagonism, conditioned behavioral and neuronal responses, Brain Res. 537 Psychopharmacology 105 (1991) 546–552.

(1990) 149–156. [31] M.D. Mauk, Roles of cerebellar cortex and nuclei in motor learning: [12] L. Chen, S. Bao, J.M. Lockard, J.J. Kim, R.F. Thompson, Impaired contradictions or clues?, Neuron 18 (1997) 343–346.

classical eyeblink conditioning in cerebellar-lesioned and Purkinje [32] D.A. McCormick, R.F. Thompson, Cerebellum: essential in-cell degeneration ( pcd ) mutant mice, J. Neurosci. 16 (1996) 2829– volvement in the classically conditioned eyelid response, Science

2838. 223 (1984) 296–299.

[13] G. Chen, J.E. Steinmetz, Microinfusion of protein kinase inhibitor [33] M.J.D. Miserendino, C.B. Sananes, K.R. Melia, M. Davis, Blocking H7 into the cerebellum impairs the acquisition but not the retention of acquisition but not expression of conditioned fear-potentiated of classical eyeblink conditioning in rabbits, Brain Res. 856 (2000) startle by NMDA antagonists in the amygdala, Nature 345 (1990)

193–201. 716–718.

[14] G. Chen, J.E. Steinmetz, Intra-cerebellar infusion of NMDA re- [34] R.G.M. Morris, R.F. Halliwell, N. Bowery, Synaptic plasticity and ceptor antagonist AP5 disrupts classical eyeblink conditioning in learning II: do different kinds of plasticity underlie different kinds of rabbits, Soc. Neurosci. Abs. 23 (1997) 783. learning?, Neuropsychology 27 (1989) 41–59.

[36] A.F. Nordholm, J.K. Thompson, C. Dersarkissian, R.F. Thompson, [41] J.E. Steinmetz, D.G. Lavond, D. Ivkovich, C.G. Logan, R.F. Lidocaine infusion in a critical region of cerebellum completely Thompson, Disruption of classical eyelid conditioning after cerebel-prevents learning of the conditioned eyeblink response, Behav. lar lesions: damage to a memory trace system or a simple per-Neurosci. 107 (1993) 882–886. formance deficit?, J. Neurosci. 12 (1992) 4403–4426.

[37] G.B. Robinson, MK801 retards acquisition of a classically con- [42] L.T. Thompson, J.F. Disterhoft, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in ditioned response without affecting conditioning-related alterations associative eyeblink conditioning: both MK-801 and phencyclidine in perforant path-granule cell synaptic transmission, Psychobiology produce task- and dose-dependent impairments, J. Pharmacol. Exp.

21 (1993) 253–264. Ther. 281 (1997) 928–940.

[38] M.M. Schugens, R. Egerter, I. Daum, K. Schepelmann, T. Klock- [43] L.T. Thompson, J.R. Moyer Jr., E. Akase, J.F. Disterhoft, A system gether, P. Loschmann, The NMDA antagonist memantine impairs for quantitative analysis of associative learning. Part 1. Hardware classical eyeblink conditioning in humans, Neurosci. Lett. 224 interfaces with cross-species applications, J. Neurosci. Methods 54

(1997) 57–60. (1994) 109–117.

[39] R.J. Servatius, T.J. Shors, Early acquisition, but not retention, of the [44] D.L. Walker, P.E. Gold, Intrahippocampal administration of both the classically conditioned eyeblink response is N-methyl-D-aspartate D- and the L-isomers of AP5 disrupt spontaneous alternation (NMDA) receptor dependent, Behav. Neurosci. 110 (1996) 1040– behavior and evoked potentials, Behav. Neurol. Biol. 62 (1994)

1048. 151–162.

[40] J.E. Steinmetz, Brain substrates of classical eyeblink conditioning: a [45] M. Watanabe, M. Mishina, Y. Inoue, Distinct spatiotemporal expres-highly localized but also distributed system, Behav. Brain Res. 110 sions of five NMDA receptor channel subunit mRNAs in the