Intelligibility and Language

Attitudes among the Tharu

Dialects of the Western

Indo-Nepal Tarai

Tharu Dialects of the Western Indo-Nepal Tarai

Compiled by Ken Hugoniot

SIL International

®2018

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2018-001, March 2018 © 2018 SIL International®

All rights reserved

Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain

This second survey of the Tharu dialects of the Indo-Nepal Tarai was undertaken mainly to replicate parts of the first Western Tharu survey carried out by Webster in 1993 (Webster 2017). Jeff Webster advised that the recorded text tests using the Kathoriya text be redone, as he was suspicious that the Kathoriya text the first survey had used was heavily mixed with Hindi and thus not not representative of the actual Kathoriya dialect. Because of this, he feared that the recorded text test results were inaccurate (see Appendix B for more information). Data collection for this survey was completed during the months of March and April 1996. The basic purposes for this survey were:

1. To replicate the Kathoriya recorded text tests done by the first survey with a new, more authentic text, and

2. To probe further into attitudes among Western Tharu groups regarding the speech of Kathoriya Tharus.

Towards fulfilling the first purpose, four recorded text tests were conducted, two in the west and two in the east of the Western Tharu area. The only real difficulty encountered was in communication when, occasionally, our subject could not speak Hindi adequately. Fortunately, there was generally a sufficiently bilingual Tharu person nearby to help. Despite this and other minor obstacles inherent in fieldwork, I feel confident with our recorded text test results.

Unfortunately, time did not permit the sort of research into attitudes toward Kathoriya that we would have desired. Only around thirty questionnaires were administered, and the results of these did not take us very far towards ascertaining general attitudes vis-à-vis Kathoriya Tharu. To further frustrate our designs, we found that those Tharus who did not live near a Kathoriya village had never heard of the Kathoriya Tharus.

iii

Maps

1 Introduction

1.1 Purpose 1.2 Goals

1.3 Summary of findings

1.3.1 Recorded text test results 1.3.2 Language attitudes

2 Study of dialect area

2.1 Dialect intelligibility—further findings 2.1.1 Procedures

2.1.2 Results 2.2 Summary

3 Language attitudes 4 General conclusion 5 Recommendations

5.1 Literature development and literacy programs 5.2 Further survey

Appendix A: International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

Appendix B: Webster’s Recommendation for Follow-up to “A Sociolingustic Survey of the Tharu Dialects of the Western Indo-Nepal Tarai”

Appendix C: Recorded Text Test Procedure Appendix D: Subject Biodata

iv

1

In the first Tharu survey (Webster 2017), it appeared that the Kathoriya variety of Tharu was a link dialect that could be understood by both the speakers of Rana Tharu to the west and of Dangora Tharu to the east, even though these two latter dialects were not very well understood by one another. Webster therefore recommended that one literature development project be done in the Kathoriya dialect that would meet the needs of all three dialects. Further developments, however, have thrown these

conclusions into doubt. Only one Kathoriya recorded text test (RTT) was tested in the Rana and Dangora areas. It turned out the text in that test had a lot of Hindi mixed in with the Tharu. This may have made it more understandable to people in the other jats2 who had some proficiency in Hindi. In addition, little information was collected in the first survey regarding the attitudes of Rana and Dangora Tharus towards the Kathoriya—attitudes that would determine its acceptability for any literature development. In light of these deficiencies, the following purposes and goals were formulated for a follow-up Western Tharu survey.

For the purposes of the previous survey (Webster 2017) and this survey, the Western Tharu area was defined as that part of the Indo-Nepal Tarai which extends southeast from U.P.’s3 Naini Tal district along both sides of the India-Nepal border as far as the eastern border of U.P.’s Gonda district. The Western Tharu area also includes Nepal’s Dang Valley, which is separated from the Tarai by a low mountain range. In India, the Western Tharu area comprises the eastern part of Naini Tal district (part of which is now Udham Singh Nagar district) and the northern border areas of Kheri and Gonda districts in U.P. In Nepal, it comprises most of the districts of Kanchanpur, Kailali, Bardiya, Banke, and Dang Deukri.

1.1 Purpose

As stated above, the basic reason for this additional survey was to determine if Kathoriya Tharu is indeed an appropriate dialect for a language project that would be acceptable to all the Western Tharu dialect groups. To fulfill this purpose, two things had to be determined:

1. Is Kathoriya Tharu as intelligible to Rana and Dangora Tharus as results from the first survey indicated?

2. What are the attitudes of Rana and Dangora Tharus towards the Kathoriya variety? If literature were developed in Kathoriya Tharu, would it be accepted by the Ranas, Dangoras, and other Western Tharu jats as a standard for Western Tharu?

If Kathoriya Tharu was found to be an inappropriate dialect for development of a general Western Tharu literature development and literacy project, then two more things had to be determined:

1. Is there any other Western Tharu dialect that would be appropriate for literature development for the whole area?

2. If there is no single dialect that is intelligible and acceptable over the whole Western Tharu area, then how many literature development and literacy projects will need to be done? Which Tharu jats would these projects involve?

1 Refer to the introduction section of Webster 2017 for an overview of the geography, people, and language of the

Western Tharu area.

2 In normal usage in South Asia, when people say jat, they mean caste. Tharus however use the term jat when

referring to the various endogamous groups, or clans, of Tharus. These groups are not castes; they are not divided on occupational lines, nor are they hierarchically stratified. In this report, the term jat refers to a Tharu endogamous group, not a caste.

1.2 Goals

The purposes of this survey were very specific, being, as it was, a follow-up to the previous more comprehensive and general survey. Therefore, the goals for this survey were also specific. In order to answer the questions posited above, the following goals were set:

1. Create another recorded text test in the Kathoriya dialect of Kheri district in U.P. Administer this test to Rana subjects at two points (both in Naini Tal district of U.P.) and to Dangora subjects at two points (as far east from Kheri district as possible).

2. Using questionnaires, investigate the attitudes of each ethnolinguistic group (especially Rana, Dangora, Kathoriya) towards the speech of the other groups.

3. Investigate the possible existence of other major distinct Tharu dialects in the Western Tharu area. If any exist, then investigate the attitudes of the other ethnolinguistic groups towards them.

1.3 Summary of findings

1.3.1 Recorded text test results

A new recorded text test was created in a Kathoriya village in Kheri district. When compared to the RTT results from the previous survey, all the tests in this survey yielded slightly lower average scores. There was only one test point, however, where the average score was more than 5 percentage points lower than the average score from the previous test. This was in a Dangora village in the Dang Valley (Dang Deukri district) of Nepal. There the average score was 82% with a high standard deviation. This makes it very difficult to determine whether the population at that test point can fully understand the Kathoriya dialect or not. The other results would seem to reinforce the results of the previous survey, indicating good intelligibility of the Kathoriya dialect among other jats located far to the east and far to the west of the Kathoriyas.

1.3.2 Language attitudes

This survey was mainly concerned with only one aspect of language attitudes. That is, what are the attitudes of each of the Tharu dialect groups toward the members of the other groups, especially the Kathoriya group? The data showed that there were no strong opinions either way by any jat about any of the other jats. There seemed to be two reasons for this. First, most of the non-Kathoriya subjects who were questioned did not live near any Kathoriya villages. Since the Kathoriya jat is quite small, these subjects had never even heard of Kathoriyas or the Kathoriya dialect. The second reason for inconclusive attitude data was simply that most Tharus seem to take a very laissez-faire attitude towards other dialects of Tharu and even towards other languages. A few individuals voiced some negative statements about one or two of the other dialects, but these were a minority.

2 Study of dialect area

2.1 Dialect intelligibility—further findings

2.1.1 Procedures

The procedures used for testing dialect intelligibility are described in Appendix C. For a more detailed description and in-depth discussion of the recorded text test procedure, refer to Casad (1974) and Blair (1990). See also the report from the previous Western Tharu survey for a good description of RTT procedures (Webster 2017).

As mentioned above, one of the main goals of this survey was to replicate the Kathoriya RTTs from the first survey using a new text. It was feared that the old text contained too much Hindi mixing and therefore could not be considered valid. The element of Hindi mixing in the Kathoriya text was only discovered some time after the previous survey was finished. A Tribhuvan University anthropologist, an expert on Tharus and their language, pointed this out. This first Kathoriya text was rendered even further invalid when we revisited the village where it had been collected. We found that the village was only 50% Kathoriya. The other 50% of the population were Dangoras. The new Kathoriya text for this survey was collected from a village just 10 to 15 kilometers from the first. According to its inhabitants, this village is around 85% Kathoriya, the other 15% being Dangoras. We were told that there are Dangora minorities living in all the Kathoriya villages. After creating the new RTT, we did a hometown test with ten subjects of the same village. In order to get some sense of the validity and purity of the new text, the following questions were asked of each subject at the conclusion of the test:

1. Is this pure Kathoriya Tharu?

2. Is this the way Kathoriya people talk in your village?

3. Was there any Dangora Tharu mixed with the Kathoriya Tharu in this story?

The answers to all three questions were unanimous. To questions 1 and 2, all the subjects replied in the affirmative. To question 3, all the subjects replied in the negative. This was perhaps a crude measure of validity, but we were faced with few other options. Thus, this RTT was chosen for this survey.

2.1.2 Results

Only one new recorded text test was developed for this survey. After being hometown tested, it was administered to subjects at four test points. Tests from the previous survey were used as hometown tests at each of the test points. These testing results are displayed in table 3, along with selected results from the previous survey. Table 1 identifies the locations of the test sites represented by the RTT codes. In each table, the test points and scores from the first survey are identified by italics.

Table 1. Locations and RTT codes of test points

RTT Code Jat Location: Village, Tehsil, District, Countrya Rana-NT2 Rana Tharu Bichuwa, Khatima, Udham Singh Nagar,b India Dang-N2 Dangora Tharu Belgunari, Dang, Dang Deukri, Nepal

Buksa-1c Buksa Madnapur, Gandepur Naini Tal, India

Dang-N1 Dangora Tharu Kotani, Dang, Dang Deukri, Nepal Dang-G1 Dangora Tharu Chandanpur, Tulsipur, Gonda, India Kathoriya-2 Kathoriya Tharu Dusgiya, Nighasan, Kheri, India

Dang-G2 Dangora Tharu Emiliya Kondar, Tulsipur, Gonda, India Kathoriya-1 Kathoriya Tharu Pavera, Pavera, Kailali, Nepal

Buksa-2 Buksa Khatola No. 1, Rudrapur, Udham Singh Nagar, India

Rana-K Rana Tharu Bangama, Nighasan, Kheri, India

Rana-NT1 Rana Tharu Sisana, Sitarganj,Naini Tal, India

a All Indian locations are in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

b Udham Singh Nagar is a newly created district, with the town of Rudrapur as its administrative headquarters.

Unfortunately, none of the maps generally available have been updated yet to depict its boundaries. Therefore, it is not shown on map 2. All the sites mentioned as belonging to Udham Singh Nagar district in this report were originally part of Naini Tal district and are shown as such on map 2.

c All italicized codes are test points from the first survey.

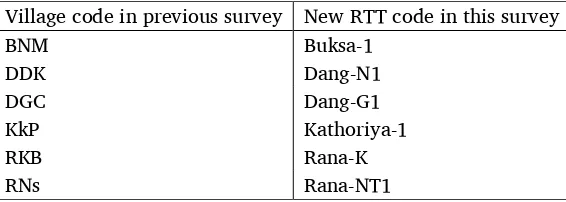

Table 2. RTT code conversion

Village code in previous survey New RTT code in this survey

BNM Buksa-1

DDK Dang-N1

DGC Dang-G1

KkP Kathoriya-1

RKB Rana-K

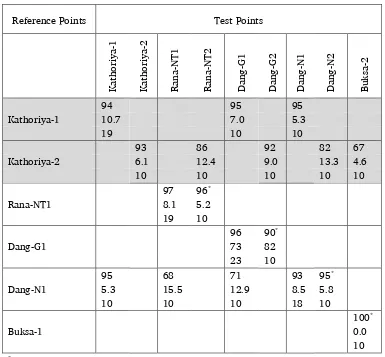

Table 3. Summary of recorded text test results * Hometown tests in the second survey were done using tests created during the first survey.

In the shaded area of table 3 are the results from the first Kathoriya RTT (reference point: Kathoriya-1) and the second Kathoriya RTT (reference point: Kathoriya-2). The Kathoriya-1 reference test is the test that was deemed unsatisfactory. The Kathoriya-2 reference test is its replacement. The text for the Kathoriya-2 test was collected in Dusgiya, a village less than 10 kilometers from Pavera, the village where the Kathoriya-1 test text was collected. The Kathoriya-2 reference test was then administered at four test points. All of these test points were within 20 kilometers of reference points from the previous survey. Therefore, reference tests from the previous survey were used for all the hometown tests. Test points that are within 20 kilometers of one another are grouped together in the boxes in table 2.

The scores on a downward diagonal from the upper left corner to the lower right corner are all hometown test scores. In the second survey, these ranged from a low of 90% on a sample of ten subjects in Gonda district (Dang-G2) to a perfect high of 100% on a sample of ten Buksa subjects in Udham Singh Nagar district (Buksa-2). The sample size for each hometown test was ten. There could be various reasons that subjects missed questions on the hometown tests. The most likely possibility is that, because the questions were so easy, their attention wandered, or perhaps they were distracted by others. Village conditions are never ideal for test taking. Sometimes babies are crying or people may be trying to whisper to the subject. Sometimes the subject is simply distracted by the novelty or embarrassment of being the center of attention. All of these things are very difficult, if not impossible, to control for in the village testing situation.

(Gonda district) and Dang-N1 (Dang Valley) were the two easternmost test points in the earlier survey. The score at each of these points was 95, showing a high degree of understanding of the Kathoriya text. Unfortunately, the Kathoriya-1 reference test was not utilized at the Naini Tal Rana test point (Rana-NT1) or at the Naini Tal Buksa test point (Buksa-1).4 Therefore, it is more difficult to make a comparison between the results of the two surveys.

In the second row of the shaded area are the results from the second survey’s testing with a new Kathoriya text from Dusgiya village in Kheri district. Four points were tested; two were far to the east of the reference point (in Gonda district and Dang valley) and two were to the west of the reference point; (one in a Rana Tharu village and one in a Buksa village, both located in Udham Singh Nagar district.) The sample size for each of these RTT was ten. These test points were chosen for their proximity to the test points in the previous survey. The scores from the two eastern test points, Dang-G2 and Dang-N2, offer a comparison to the scores from the previous survey. In both cases the scores were lower in the second survey. At 92%, the Dang-G2 score was only three percentage points below that of Dang-G1 in the previous survey, and the standard deviation was only two points higher. These differences in scores are effectively negligible given the high probability for error in the village testing situation. The Dang-N2 score from the Dang valley, however, tells a much different story when compared to its counterpart, Dang-N1. The Dang-N2 subjects scored thirteen points lower than the Dang-N1 subjects. The high standard deviation of 13.3 at Dang-N2, though, shows that there was a much wider variance of understanding of the second test than of the first.

It is very difficult to draw any definite conclusions from the scores of the Dang-N2 test. Experience has shown that an arbitrary score of 80% is the rough cut-off point to indicate adequate intelligibility of a text by a subject. Anything below 80% is considered inadequate. So an average score of 82% is very near the intelligibility borderline. The high standard deviation also indicates that some subjects scored well above that average while some scored well below it. Thus, some understood the test adequately while others did not. The test was followed by a few “post-RTT” questions. When asked how much of the text they understood, four out of ten subjects said that they understood all of it and two out of ten said that they understood most of it. The others indicated that they understood lesser amounts. Seven out of ten subjects said that the Kathoriya text was only a little bit different than the way they speak.

Unfortunately, these self-reported data do not help to clarify the question of intelligibility in this case. It is interesting that despite the high average score on the Kathoriya-2 RTT at Dang-G2, only one subject at that site reported that he had understood all of the Kathoriya text. In addition, seven out of ten subjects at Dang-G2 said that the text was very different than the way they speak. This is very confusing in light of the answers of the Dang-N2 subjects to the same question. However, since no qualifications were given in the question for the adjectives “very” and “a little bit”, it is difficult to determine what a subject may have been thinking when he or she answered the question. It would perhaps be best to put little or none of the weight of our analysis on these self-reported data.

It is a dangerous venture to attempt to find any statistical correlation with a sample size of only ten. But desperation is the mother of many rash undertakings, so we will posit two possible, and very

tentative, correlations between the scores and the biodata of the Dang-N2 test subjects. Despite the sample size, the first correlation is really not all that daring. If the average scores of male and female scores on any given RTT are contrasted, the male scores will almost invariably be found to be higher. There are a number of reasons for this: males are on average more educated than women, and they tend to travel more often and farther from the village. People with higher educations tend to score higher on RTTs because they have presumably taken tests before in school and may be more familiar with the concept. They may also have learned some of the national language in school. If the test text includes some borrowings or cognates from the national language, people with some education will probably understand more of the text than those with little or no education. People who often travel far from the village frequently encounter, and sometimes learn, other varieties of speech. If they have encountered the variety of speech contained in the test text they will naturally understand more of it than someone who has seldom or never left the village. The male and female scores on the Dang-N2 test exhibit this

same discrepancy between the sexes. The males averaged a score of 88% while the females averaged only 71%.

The second correlation is much more tentative: the results seem to point to a direct relationship between age and score. In other words, the higher the subject’s age, the higher the score. This is, however, only a very general trend. When age and scores are statistically correlated, they yield a coefficient of .68. To put this into perspective, a coefficient of 1 would mean that there was an exact correlation between age and scores. An unlikely coefficient of 0 would mean that there was no

correlation at all between age and scores. A coefficient of .68 indicates only a very tentative correlation at best. One possible reason for this trend of older people doing better on the test could be that they have had more contact with other Tharu jats over the years. It could also be a product of recent political and educational trends. The concerted efforts of the government of Nepal to institute and encourage the use of the national language, Nepali, among the Tharus and throughout the country may have had the following result: instead of using a form of Tharu for wider communication with other Tharu jats, the Tharus in Dang Valley and in other parts of Nepal are perhaps now using Nepali as their language of wider communication. These are only guesses, but they definitely deserve further research. It would be good to see if this trend holds in further RTTs and, if so, to investigate further into what the reasons might be. These RTTs would, of course, require larger sample sizes in order to validate the scores and correlations derived from them.

In the shaded area of the second column of table 3 is the score for the Kathoriya reference test administered in Bichuwa (Rana-NT2), a Rana Tharu village in Udham Singh Nagar district, west of Kheri district. The Rana-NT2 subjects averaged 86% on the Kathoriya-2 Kathoriya RTT with a high standard deviation of 12.4. This again is a rather difficult score to draw any conclusions from since scores ranged from 64% to 100%. This test exhibited no hint of an age-score correlation. The high standard deviation, however, can be partly explained by the wide gap between the scores of men and women. The average score for males at the Rana-NT2 test point was 93% while the average score for females was 76%. There was also a gap between the average scores of people who had received some education and those with no education. These average scores were 91% and 80% respectively. After taking the test, nine of the ten subjects reported that they had understood all of the text.

In the shaded area of the last column of table 3 is the result of the Kathoriya-2 reference test administered in Khatola No. 1 (Buksa-2), a Buksa village in Udham Singh Nagar district. The average score of 67% for this RTT was dramatically lower than any of the others. There was a high standard deviation of 14.6. No obvious relationship between scores and subject biodata is evident. The low average score, however, allows for much more confident conclusions to be made regarding the ability of the subjects to comprehend the Kathoriya text. Aside from one score of 100% (from the most educated subject in the sample), the rest of the scores ranged only from 50% to 77%. Thus, at the Buksa-2 test point, the Buksa subjects’ ability to understand the Kathoriya text was quite a bit poorer than that of the Tharu subjects at any of the other test points. It is interesting that the lexical similarity data from the first survey (Webster 2017) show that the two Buksa points BNM and BNT shared 69% and 66% similarity respectively with the Kathoriya point KkP (Kathoriya-1 in the present survey). This compares closely with the 67% intelligibility score of the Buksa-2 test point on the Kathoriya-2 reference test.

In the first survey, Buksa subjects did very well on a Rana reference test from nearby Sisana (Rana-1). The average score on that test was 95% (Webster 2017). Unfortunately, the first Kathoriya text (Kathoriya-1) was not tested at the Buksa test point. However, Webster and his colleagues made the following fallacious assumption, based on other RTT data they had collected:

[Test] points [Rana-NT1] and [Buksa-1] were not tested on [Kathoriya-1]; however, we can extrapolate from the results we do have. Average recorded text test scores among [Rana-NT1], [Rana-K] and [Buksa-1] are uniformly high—all above 95%. Based on these high scores, we could have chosen any one of these points as representative of the other two. This suggests that [Rana-NT1] and [Buksa-1] should not score significantly different from [Rana-K] (90%) on the [Kathoriya-1] test. (Webster 2017).

sites that was tested on the Kathoriya-1 test was Rana-K. Rana-K is located very near (within 20 kilometers) to the Kathoriya-1 reference point. The other two sites are much farther away in another district. Admittedly, though, if the first Kathoriya text was heavily mixed with Hindi, as was suspected, then the Buksa subjects at Buksa-1 might, indeed, have scored somewhere around 90%. Lexical similarity data from the first survey (Webster 2017) showed the Buksa wordlists to be the most lexically similar to standard Hindi (80% and 83%) of all the wordlists collected.

In the first survey the Buksas were assumed to be one of the Tharu jats, though it was mentioned that the Buksas are recognized as a separate Scheduled Tribe by the government of India (Webster 2017). It is the conclusion of this survey, however, that the Buksas are indeed a separate tribe rather than a Tharu jat. All the Buksas that were asked about this averred that they were not Tharus. In addition, the Rana Tharus living nearby the Buksas said the same thing—the Buksas are not Tharus.

2.2 Summary

It seems clear that, however close it may be to the Rana speech varieties nearby, the Buksa speech variety must be considered a separate dialect from the Kathoriya speech variety in Kheri district. This is the only clear-cut distinction these intelligibility study results will allow us.

It is interesting that the Dangoras to the east, in Gonda district (Dang-G2), scored better than the Ranas to the west (Rana-NT2) who are actually closer geographically to the Kathoriya reference point. This may be because of the presence of Kathoriya villages not far from Emiliya Kondar (Dang-G2). The villagers in Dang-G2 reported that this was the case. The subjects in both Rana-NT2 and Dang-G2, however, seemed to adequately understand the Kathoriya text. Obviously, the Tharus of Dang Valley understand a large portion of the Kathoriya speech variety. It should not be assumed, however, that their understanding of the Kathoriya speech variety is enough to make Kathoriya Tharu an adequate medium for literacy development in Dang Valley. The Dang Valley subjects scored much lower on the Kathoriya RTT the second time around. This new score was somewhere on the intelligibility borderline

traditionally used to demarcate separate dialects.

The data collected in this survey should not be considered without reference to the data from Webster’s survey. In RTTs administered by that survey, the Rana subjects did poorly when tested on western Dangora texts (Webster 2017). The Dangora subjects averaged below 80% whenever tested with Rana texts. If Kathoriya cannot be considered a “link” dialect, uniting all the varieties of Western Tharu, then we have to say that the Rana and Dangora varieties are separate and distinct dialects. The

differences apparent between the speech of Dang Valley and all the other varieties (including other Dangora varieties) pose a question as to what its status should be. Is it different enough from everything else to enable us to boldly bestow separate “dialect” status upon it? Probably not, but our data show that it contains at least enough differences to make it distinct and slightly separate from the other varieties of Western Tharu.

3 Language attitudes

The study of language attitudes attempts to describe people’s attitude towards the different speech varieties that are known to them, and about the choices people should make with regard to language use. In this survey, language attitudes among the Tharu were studied through the use of an orally administered questionnaire.5 Some research into Tharu language attitudes was done by the previous

5 These questions were integrated into a longer questionnaire used to gather data for a separate research project

from the same respondents (Kilgo, forthcoming). The other questions and their responses concerned language use among the Tharus and attitudes vis-à-vis Hindi. Those questions, though interesting, do not fall within the

survey. It was hoped that in this second survey more thorough data could be obtained regarding these attitudes. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, only a few questionnaires were actually collected and these not very systematically. In the current survey, priority was given to RTT data rather than language attitude data. Because the sample is so small, any conclusions drawn from them would be unreliable. We will, however, venture a few comments about the scanty data we have.

The first four questions were quickly abandoned when we realized that no one could supply a coherent answer to them. It seemed that the notion of people in one place speaking Tharu better than people in another place was incomprehensible to them. The lack of understanding of these questions makes sense in light of the fact that there is apparently no standard or prestige variety of Tharu.

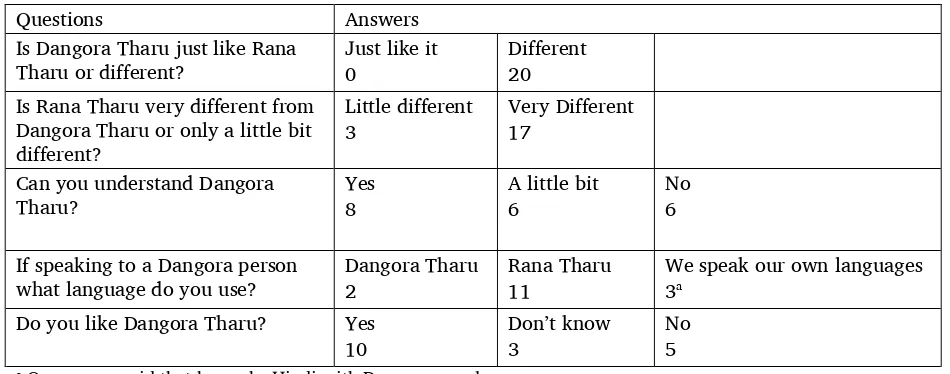

In an attempt to get information on attitudes toward specific Tharu jats, a matrix was devised in which the same questions were repeated in regard to each of the other jats successively. We found that almost all Tharus were only familiar with other Tharu jats in their own immediate area, i.e., within their district. The Ranas and Dangoras, being widespread, were known to everyone, but smaller jats like the Kathoriyas were often unknown to the respondents. Only a few questionnaires were administered to Dangora and Kathoriya subjects, but 26 were administered to Rana subjects. Only six of these subjects had heard of the Kathoriya jat. Of these six subjects, five lived in Bangama village, Kheri district, very near to Kathoriya villages. The other twenty subjects were all from the villages of Bichuwa and Amau in Udham Singh Nagar district and did not live close to any Kathoriya villages. Only one of these subjects had heard of the Kathoriya jat. All of the respondents had heard of the Dangora jat. Because so few of the respondents were able to answer questions about the Kathoriyas, only the responses of the Rana subjects to the questions about the Dangora dialect have been included here. The answers of the Rana

respondents are summarized in table 4, which shows the number of people who gave each response.

Table 4. Language attitude survey results

Questions Answers

Is Dangora Tharu just like Rana Tharu or different?

Just like it 0

Different 20 Is Rana Tharu very different from

Dangora Tharu or only a little bit different?

If speaking to a Dangora person what language do you use?

Do you like Dangora Tharu? Yes 10

Don’t know 3

No 5

a One person said that he spoke Hindi with Dangora people.

Notice that though all the respondents had heard of the Dangora jat, only twenty were able to answer the rest of the questions. All twenty respondents said that Dangoras speak differently than Ranas. Seventeen respondents said that there is a large difference between the two dialects. Eight respondents said that they could understand Dangora Tharu. Twelve said either that they could not understand Dangora Tharu or they could only understand a little bit of it. Eleven of the respondents said that when speaking with a Dangora they speak in the Rana dialect. Only two said that they speak in the Dangora variety. A few of the others said that when speaking to a Dangora person, each person speaks in his own dialect. Half of the respondents said that they liked the Dangora dialect. A quarter of the respondents said that they didn’t like it. The other quarter had no opinion.

heard was good Tharu or not. The answers reported below refer only to the Kathoriya-2 text. (Ten subjects were tested at each site, but not all of the post-RTT questions were answered by every subject.)

At the Rana-NT2 test site only one subject thought that the Kathoriya text was good Tharu, four said that it was not good Tharu and four more said that it wasn’t even Tharu at all! In this survey, this was the only indication that there may be some negative perceptions among other groups of the Kathoriya speech variety. Seven of the subjects were able to say that the speaker of the text was from somewhere to the east, but only one person was able to identify the speaker’s jat. That person had traveled to the speaker’s home area. Most of the subjects were unable to guess at the speaker’s jat.

The Dang-N2 subjects were more positive towards the Kathoriya text. Six subjects said that the text was good Tharu, three gave no answer and only one replied negatively, saying that it was “not pure Tharu”. Only four subjects were able to say that the speaker was from the west. The others were unable to give even a general direction for his location. Two subjects accurately labeled the speaker as a Kathoriya, one said he was a Rana and one said he was a Dangora. The rest were unable to venture a response.

4 General conclusion

The following conclusions and the subsequent recommendations should be viewed only in reference to the conclusions and recommendations of the previous Western Tharu survey (Webster 2017). Essentially, they are additions and corrections to the conclusions and recommendations found in Webster.

Webster enumerates four major specific findings of his survey in regard to language development and literacy programs in the Western Tharu area:

1) a vast majority of the population is not likely to be adequately bilingual in Hindi; 2) the Tharu language is widely used in nearly every domain, and attitudes are very positive

towards it;

3) Kathoriya Tharu appears to be widely understood among all of the different Tharu speech varieties tested in the Western Indo-Nepal Tarai; and,

4) lexically, Kathoriya Tharu is a central point midway between the more divergent Rana and Dangora varieties (Webster 2017).

The second survey encountered no data that would cast any doubt on the first two findings. Nor did subjective personal observations provide any reason to doubt these findings. We did not collect any wordlists in this survey so we have no data that could possibly refute the fourth finding. The results of the RTTs done in this survey, however, would appear to throw some doubt on Webster’s third finding. The average score for the Dang Valley (Dang-N2) subjects was 13 percentage points lower than the score of the Dang Valley subjects in the first survey. At 82% this score is on the borderline of acceptable intelligibility. A high standard deviation makes it even more of a borderline intelligibility case.

In addition, the Buksa tribe of Naini Tal district in U.P. was not tested on the Kathoriya test in the first survey. In this survey, subjects in a Buksa village were tested with the Kathoriya RTT. Their average score was only 67%. This indicates poor intelligibility of Kathoriya Tharu.

5 Recommendations

5.1 Literature development and literacy programs

literature development and literacy programs for the people of Dang Valley. Other factors, both linguistic and non-linguistic, should therefore be considered.

One of these factors is the relative sizes of the various Tharu jats. The Rana and Dangora jats are by far the largest, their populations dwarfing the populations of the others. The Kathoriyas are a much smaller jat. We discovered that, unless they lived near a Kathoriya village, other Tharus had never heard of the Kathoriyas. This could prove problematic if literature were to be developed in Kathoriya Tharu for use by Ranas and Dangoras. They might reject it if it was too different and was from some small,

unrecognized jat. There is very little evidence pointing to strong negative attitudes among the Tharus in regard to each other’s speech. But if such attitudes were to surface, a small jat with no special claim to status would be unlikely to win the respect of larger jats.

Another factor to keep in mind, especially in the case of the Dang Valley Tharus, is the effect of second languages on the way Tharus speak. Tharus in India learn Hindi as their second language while Tharus in Nepal learn Nepali. It became quite evident to us during the course of our research that there were differences in speech between Nepali Tharus and Indian Tharus that seemed to be caused by influences from their respective national languages. One wonders if perhaps the Tharu dialects are diverging as people on both sides of the border gradually mix more and more of the national language with their own. Any dichotomy caused by the influence of the national languages would likely be reflected in the speech of the Ranas in the west and the Dangoras in the east. The majority of Dangora Tharus live in Nepal while the majority of Rana Tharus live in India.

Demographic and geographic factors pose yet another caution against using Kathoriya as a single literature development and literacy medium for the whole Western Tharu area. The Western Tharu population numbers in the hundreds of thousands. This large population is spread linearly across a vast area of the Indo-Nepal Tarai. From east to west this area spans around 350 kilometers. Given the language variance across this area, it is very likely that some kind of adaptations may prove to be necessary regardless of which kind of language development approach is taken.

In light of the RTT results and the above observations, it is difficult to make any unequivocal recommendation for literature development and literacy programs in the Western Tharu area. Essentially, there are two alternative approaches to take for language projects in this area. The first would be a one-project approach. This project would attempt to use Kathoriya as an improvised standard for the whole Western Tharu area. The second approach would involve two parallel projects, one in the west among the Rana Tharus and one in the east among the Dangora Tharus. It is still possible that a single Kathoriya-based project would be understood and accepted by people in the whole area. If it worked, this would be the most efficient solution. It seems, however, that there are many potential pitfalls awaiting such an approach. A two-project approach, using the Rana and Dangora varieties, would be the more conservative and probably more satisfactory solution. This survey recommends such a two-project approach. In the end, two sets of materials might prove unnecessary. But the two jats are so large and, in many ways, culturally disparate that it seems very likely that some adaptation would be

necessary in order for each jat to accept the materials as its own.

Obviously, it would be good to have yet more language data and more demographic, cultural and political information about the Western Tharu area. But, given the size of the area and the limited resources available to a short-term survey effort, it seems unwise to attempt any further surveys of this kind in this area. A very huge effort would be needed to gather what might be considered the “critical mass” of data required for an ideal recommendation. This is probably not necessary. There are not the resources for such a task and it is likely that we have accumulated enough good “informed guesses” to base a decision upon. It is inevitable that any initial project plan will be modified over time. Even with better decision-making data, any plan for Western Tharu could very well undergo drastic modifications along the way. This would seem to be the nature of such an ambitious plan. Persons involved in these projects should be aware of the possibility of major changes in the project plan and be prepared to be flexible in the face of such a possibility. If this criterion is met, then there seems to be no reason to delay the creation and implementation of a two-project plan.

The Rana project should probably be undertaken in U.P.’s Udham Singh Nagar district or Kheri district since these areas seem to be the most predominantly Rana. In light of the following factors, it seems that Kheri district would be a somewhat better choice: 1) The Rana population of Kheri district is more isolated and traditional than that of Udham Singh Nagar district. In fact, many women still wear the traditional Rana dress. The area is bounded on the north by the Nepal border and on the south by a large tract of forest that makes up Dudhwa National Park. The Rana population of Udham Singh Nagar district is somewhat more educated and progressive than the Kheri population. As a result, they are probably more bilingual in Hindi, whereas the speech of the Kheri Ranas may be more free of Hindi influences. 2) The Rana population of Kheri is more homogenous than that of Udham Singh Nagar district. In Udham Singh Nagar, many Kumaonis and other hill people have come south from the mountains, bought up Tharu land, and settled in their villages where they have assumed a dominant political and economic position. Most of them also consider themselves higher caste than the Tharus. The population of many villages in Udham Singh Nagar district has become nearly 50% Pahari. In contrast, the Kheri district area is basically completely Tharu. Most are Rana Tharu, but a few villages are Kathoriya and there are some Dangora immigrants living in the Rana and Kathoriya villages. With these considerations in mind, we recommend that a Rana project be initiated in a village in U.P.’s Kheri district or, alternately, in the contiguous border region of Nepal’s Kailali district.

If a single Kathoriya project were undertaken, Dusgiya village or one of the villages near it in U.P.’s Kheri district or in Nepal’s Kailali district would be suitable. Pavera, the village in Kailali mentioned in the recommendation of the previous survey, would not be an acceptable base for language development since it is only 50% Kathoriya.

Note that in the first survey, the Buksa people were assumed to be a Tharu jat. We discovered that this is not the case. They asserted that they are actually not Tharus, and when we asked Tharus from nearby villages they affirmed that this is true—the Buksas are not Tharus. Their language also seems to be somewhat different from that of the other Tharus. They obviously had difficulty in understanding the Kathoriya text. This indicates that a separate Buksa project could be needed in the Naini Tal district of U.P. The results of the previous survey, however, hint at the possibility that there may be a high degree of bilingual ability among the Buksas. Additionally, the previous survey found that Buksa subjects understood a text from a Rana village in the same district very well. This is a matter that requires further study before any recommendation can be made.

5.2 Further survey

We affirm the opinion of Webster: “The biggest need for further survey lies east of Gonda district (Dang District in Nepal)… The different Tharu varieties along the Nepal-India border east to the eastern border of Nepal need to be surveyed, and dialect centers determined” (Webster 2017). This question is being addressed to some extent in current research by Ed Boehm (forthcoming) through the collection of wordlists and the use of historical-comparative methods.

If Kathoriya Tharu were to be chosen as a unifying dialect for literature development, then another of Webster’s recommendations for further survey should also be followed. Specifically, “The Kathoriya Tharu recorded text test should be tested in selected points to determine how far this language variety will reach”. Webster recommended use of the Kathoriya-1 text but we of course recommend the Kathoriya-2 text instead. Regarding the use of Kathoriya Tharu as a link dialect for literature development, Webster goes further to recommend the following: “Before extensive literature

development is begun, further language attitude studies are necessary to probe attitudes towards oral and written Kathoriya Tharu.” If Kathoriya Tharu is found to be an unacceptable medium for literature development, then we recommend that our above suggestions for a two-project (Rana and Dangora) approach be followed.

populations of Tharus. The speech of these populations needs to be assessed to determine which dialect would most likely fit their literacy needs.

It would be informative to compare the speech of Tharu villages that are directly opposite each other across the India-Nepal border. For example, subjects in an Indian Tharu village could be tested on a RTT collected in a Nepali Tharu village directly to the north. Also, wordlists could be collected at both sites. These data would probably be most meaningful if the two villages were each at least 25 to 30 kilometers from the border. These texts and wordlists could be collected from three to five spots across the east-west Tharu continuum in the Western Tarai. Such data might help to determine what degree of influence the respective national languages are having on the speech of Tharus. There are indications that such cross-border differences could be rather large. In Webster’s survey, subjects in a village in Dang Valley (DDK) scored only 71% on a RTT from a village directly south of it (DGC) in India. Reciprocally, when subjects in the same Indian village were tested with a text from the village in Dang Valley, they had a very similar average score of 72% (Webster 2017). These villages were no more than 40 kilometers apart.

Webster called for further bilingualism testing in Nepali in various Tharu communities in West Nepal. We second this recommendation.

Further bilingual testing in Hindi should also be done among the Buksa in Naini Tal district in U.P. If bilingualism in Hindi is found to be low, then the Rana Tharu of Udham Singh Nagar district should be further tested among the Buksa to determine if it would suffice for literature development or if a

15

The Tharu survey was done in Fall 1992 [see Webster 2017]. Since then, the results and the

recommendations have been a bit unsettling to me. There is considerable diversity among the Tharu varieties from Naini Tal District (U.P., India) in the west to Dang District in Nepal in the east. Despite this diversity, one variety midway between the two extremes seemed to be well understood in all the test areas on the RTTs, and this same variety was also a central point according to lexical similarity. Minimal language use and attitude questionnaires raised a question about this one variety. The recommendations unequivocally stated that this middle variety, called Kathoriya Tharu, should be the point for further language development and translation. The final recommendation, regarding further survey, gave this caution:

Before extensive literature development is begun, further language attitude studies are necessary to probe attitudes towards oral and written Kathoriya Tharu. If literature in this variety proves unacceptable, because of negative attitudes or because of poor understanding of Kathoriya literature, then further survey will be needed to determine alternate centers for literature development. The data suggests that a Rana Tharu point in Nainital District (like Sisana, RNs) would be a good choice to reach the Rana and Buksa groups; the Kathoriya village of Pavera appears to be the best point to reach the Dangora group.

Given this context, Ed Boehm and I decided to do some further checking while in Kathmandu. Ed was able to meet with an anthropologist at CNAS, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, who grew up in Dang Valley and speaks fluent Tharu and Nepali. Though not a Tharu, he definitely has an insider’s perspective and has been quite active in Tharu research, and is well informed about recent efforts to promote Tharu language and culture. He listened to each of the texts used in the RTTs and gave his impression about where the text was from, the kind of Tharu it represented, and how much he could understand of it. The only surprise came when he listened to the Kathoriya Tharu text. He felt it was heavily mixed with Hindi, a fairly obvious feature that we had not been aware of. Of more importance, though, was his impression that this variety, mixed with so much Hindi, would not be acceptable to those from Dang Valley.

Certainly, a sample of one is not enough to rewrite all of the recommendations from this report, but it does give some confirmation to our suspicion voiced in the above recommendation about further survey. The basic conclusions are still valid. All evidence does point to Kathoriya Tharu being well understood as a “link” dialect, but it is probably more mixed with Hindi, which probably has contributed to it being understood over a broad area. The real question is, “How acceptable will such a mixed variety be?” This one insider strongly suggests that it will not be acceptable for Dang Tharus.

16

The extent to which speakers of related linguistic varieties understand one another can be studied by means of tape-recorded texts. Such studies investigate whether speakers of one variety understand a narrative text in another variety and are able to answer questions about the content of that text. The accuracy with which subjects answer these questions is taken as an index of their comprehension of that speech form. From the percentage of correct answers, the amount of intelligibility between speech forms is inferred. The recorded text testing used in this survey is based on the procedures described in Casad (1974) and Blair (1990).

Short, personal-experience narratives are deemed to be most suitable for recorded text testing in that the content must be relatively unpredictable and the speech form should be natural. Folklore or other material thought to be widely known is avoided. A three- to five-minute story is recorded from a speaker of the regional vernacular, and then checked with a group of speakers from the same region to ensure that the spoken forms are truly representative of that area. The story is then transcribed, and a set of comprehension questions is constructed based on various semantic domains covered in the text. Normally, a set of fifteen or more questions is initially prepared. Some of the questions will prove unsuitable—perhaps because the answer is not in focus in the text, or because the question is confusing to native speakers of the test variety. Unsuitable questions are deleted from the preliminary set, leaving a minimum of ten final questions for each RTT. To ensure that measures of comprehension are based on the subjects’ understanding of the text itself and not on a misunderstanding of the test questions, these questions must be recorded in the regional variety of the test subjects. This requires an appropriate dialect version of the questions for each RTT for each test location.

In the RTTs used in this study, test subjects heard the complete story text once, after which the story was repeated with test questions and the opportunities for responses interspersed with necessary pauses in the recorded text. Appropriate and correct responses are directly extractable from the segment of speech immediately preceding the question, such that memory limitations exert a negligible effect and indirect inferencing based on the content is not required. Thus the RTT aims to be a close reflection of a subject’s comprehension of the language itself, not of his or her memory, intelligence, or reasoning. The average or mean of the scores obtained from subjects at one test location is taken as a numerical indicator of the intelligibility between speakers of the dialects represented.

In order to ensure that the RTT is a fair test of the intelligibility of the test variety to speakers from the regions tested, the text is first tested with subjects from the region where the text was recorded. This initial testing is referred to as the hometown test. The hometown test serves to introduce subjects to the testing procedure in a context where intelligibility of the dialect is assumed to be complete, since it is the native variety of test subjects. In addition, hometown testing insures that native speakers of the text dialect can accurately answer the comprehension questions used to assess understanding of the text in non-native dialect areas. Once a text has been hometown tested with a minimum of ten subjects who have been able to correctly answer the selected comprehension questions, the test is considered validated.

It is possible that subjects may be unable to answer the test questions correctly simply because they does not understand what is expected of them. This is especially true with unsophisticated subjects or those unacquainted with test taking. Therefore, a very short pre-test story with four questions is recorded in the local variety before beginning the actual testing. The purpose of this pre-test is to teach the subject what is expected according to the RTT procedures. If the subject is able to answer the pre-test questions, it is assumed that he or she would serve as a suitable subject. Each subject then participates in the hometown test in his or her native variety before participating in RTTs in non-native varieties. Occasionally, even after the pre-test, a subject fails to perform adequately on an already validated hometown test. Performances of such subjects are eliminated from the final evaluation, the assumption

being that uncontrollable factors unrelated to the intelligibility of speech forms are skewing such test results. In this study, subjects performing at levels of less than 80 percent on their hometown test were eliminated from further testing.

When speakers of one linguistic variety have had no previous contact with the variety represented by the recorded text, the test scores of ten subjects from the test point tend to be more similar—

especially when the scores are in the higher ranges. Such consistent scores are often interpreted to be closer reflections of the inherent intelligibility between speech forms. If the sample of ten subjects accurately represents the speech community being tested in terms of the variables affecting

intelligibility, and the RTT scores show such consistency, increasing the number of subjects should not significantly increase the range of variation of the scores.

However, when some subjects have had significant previous contact with the speech form recorded on the RTT, while others have not, the scores usually vary considerably, reflecting the degree of learning that has gone on through contact. For this reason it is important to include a measure of dispersion that reflects the extent to which the range of scores varies from the mean, i.e., the standard deviation. On a RTT with 100 possible points (that is, 100 percent), standard deviations of 15 or more are considered high. If the standard deviation is relatively low, say 10 or less, and the mean score for subjects from the selected test point is high, the assumption is that the community as a whole probably understands the test variety rather well, either because the variety in the RTT is inherently intelligible or because this variety has been acquired rather consistently and uniformly throughout the speech community. If the standard deviation is low and the mean RTT score is also low, the assumption is that the community as a whole understands the test variety rather poorly, and that regular contact has not facilitated learning of the test variety to any significant extent. If the standard deviation is high, regardless of the mean score, one implication is that some subjects have learned to comprehend the test variety better than others. In this last case, inherent intelligibility between the related varieties may be mixed with acquired

proficiency that results from learning through contact.

High standard deviations can result from other causes, such as inconsistencies in the circumstances of test administration and scoring or differences in attentiveness or intelligence of subjects. Researchers involved in recorded text testing need to be aware of the potential for skewed results from such factors, and to control for them as much as possible through careful test development and administration.

Questionnaires administered at the time of testing can help researchers discover which factors are significant in promoting contact that facilitates acquired intelligibility. Travel to or extended stays in other dialect regions, intermarriage between dialect groups, or contacts with schoolmates from other dialect regions are examples of the types of contact that can occur.

In contrast to experimentally controlled testing in a laboratory or classroom situation, the results of field-administered methods such as the RTT cannot be completely isolated from potential biases.

Recorded texts and test questions will vary in terms of their relative difficulty and complexity or in terms of the clarity of the recording. Comparisons of RTT results from different texts need to be made

18 Village Code Location

DSG Kathoriya-2 Dusgiya (Kheri district, U.P.)

BCA Rama-NT2 Bichuwa (Udham Singh Nagar district, U.P.) BGM Rama-K Bangama (Kheri district, U.P.)

AMU Amau (Udham Singh Nagar district, U.P.) EMK Dang-G2 Emiliya Kondar (Gonda district, U.P.) BGR Dang-N2 Belgunari (Dang Deukri district, Nepal) KTL Buksa-2 Khatola No. 1 (Udham Singh Nagar dist., U.P.)

SUB. # Tharu jat Sex Age Education Occupation

KTL-08 Buksa M 16 5 agriculture

KTL-09 Buksa M 48 5 agriculture

KTL-10 Buksa M 20 10 agriculture

KTL-11 Buksa M 18 10 agriculture

KTL-12 Buksa M 20 5 agriculture, shopkeeper

21 Kathoriya-2 HTT (hometown test) (Kathoriya-2 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Total %

DSG-01 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 91 DSG-06 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 10 10 105 95 DSG-07 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 DSG-08 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 91 DSG-09 10 5 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 95 86 DSG-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 DSG-11 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 105 95 DSG-12 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 5 10 5 90 82 DSG-13 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 100 91 DSG-14 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 DSG-01 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 91 x (mean/average score) = 93%

s (standard deviation) = 6.1 n (number of questions) = 10

Rana-NT2 HTT (Rana-NT1 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total

BCA-01 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 BCA-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-04 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-05 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 BCA-06 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-07 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 BCA-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-09 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BCA-11 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 x = 96%

Rana-NT2 RTT (recorded text test) (Kathoriya-2 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Total %

BCA-01 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 0 0 0 10 70 64 BCA-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 0 10 90 82 BCA-04 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 100 91 BCA-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 100 91 BCA-06 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 BCA-07 0 10 10 10 10 5 10 10 0 10 0 75 68 BCA-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 BCA-09 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 100 91 BCA-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 105 95 BCA-11 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 90 82 BCA-01 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 0 0 0 10 70 64 x = 86%

s = 12.4 n = 11

Dang-G2 HTT (Dang-G1 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total

EMK-01 10 0 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 80 EMK-02 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 0 10 10 80 EMK-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 EMK-04 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 90 EMK-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 EMK-06 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 EMK-07 10 10 0 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 80 EMK-08 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 90 EMK-09 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 10 90 EMK-11 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 90 x = 90%

Dang-G2 RTT (Kathoriya-2 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Total %

EMK-01 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 100 91 EMK-02 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 100 91 EMK-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 EMK-04 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 100 91 EMK-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 EMK-06 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 90 82 EMK-07 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 EMK-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 10 105 95 EMK-09 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 0 0 10 10 80 73 EMK-11 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 x = 92%

s = 9.0 n = 11

Dang-N2 HTT (Dang-N1 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total

BGR-01 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BGR-02 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 BGR-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BGR-04 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BGR-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 BGR-06 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 10 90 BGR-07 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 85 BGR-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 95 BGR-09 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 BGR-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 x = 95%

Dang-N2 RTT (Kathoriya-2 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4* 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Total %

BGR-01 0 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 90 90 BGR-02 5 0 10 0 0 10 10 10 10 0 55 55 BGR-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 90 90 BGR-04 0 0 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 70 70 BGR-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 90 90 BGR-06 10 10 0 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 80 80 BGR-07 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 0 0 70 70 BGR-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 100 BGR-09 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 0 80 80 BGR-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 0 90 90 *Question 4 disqualified.

x = 82% s = 13.3 n = 10

Buksa-2 HTT (Buksa-1 text)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total

KTL-01 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-02 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-03 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-05 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-07 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-08 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-09 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-11 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 KTL-12 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 x = 100%

Buksa-2 HTT (Kathoriya-2)

Subject 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Total %

KTL-01 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 110 100 KTL-02 10 10 10 0 10 0 10 10 0 0 0 60 55 KTL-03 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 0 0 10 80 73 KTL-05 0 0 10 10 10 0 0 10 0 10 10 60 55 KTL-07 5 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 0 10 10 85 77 KTL-08 10 0 10 0 10 0 10 10 10 0 10 70 64 KTL-09 10 10 10 0 10 0 10 10 0 0 10 70 64 KTL-10 5 10 0 10 10 0 0 10 0 10 10 65 59 KTL-11 5 10 0 0 10 0 10 10 0 0 10 55 50 KTL-12 10 10 10 10 10 0 10 10 0 10 0 80 73 x = 67%

26

F.1 Kathoriya-1 text: “The Tiger and the Bullock Cart”

Sentence 1:

həmɾe gʰəɾt̪i kʰɐnɐ kəⁱli. (we)our house(in) food ate We ate our food at home.

Sentence 2:

ɔ kʰɐnɐ kʰɐⁱke əpnɐ pɐs me ek gʰəɾ kɐ ɾəhẽ ʊəjn

and food ate(after) our near in one house was ther to.them

kəjli ki t̪ʋmse həli kʰəu. told you quickly eat

And after eating we told our neighbors, “Eat quickly!”

Sentence 3:

əᵘɾ əb d̪eɾ hoⁱt̪e.

and now late getting Now it’s getting late.

Question 1: After eating, what did they say to their neighbors? Answer 1: “Eat quickly. It’s getting late.”

Sentence 4:

ɔɾ kʰərijɐ kʰɐʈe dʒɐⁱke.

and grass cut to.go And (we have to) go to cut grass.

Sentence 5:

kʰəɾija kʰɐʈe tʃəl d̪eli hĩjat̪ t̪ɔ əpnɐ ʌɾɐmt̪i həmse dʒɐⁱt̪i ɾɐhi. grass cut go our usually we going were When we went to cut grass we went along our usual way.

Sentence 6:

koj git gajt̪ ɾəhe t̪o koj hʋk:ɐ pije koj biɖi some song sing was someone pipe smoked someone bidi

pije koj mədʒe əⁱse dʒɐit̪ ɾəhi mət̪ləb ʌⁱsehĩ

smoked someone enjoyment like.this going were because this.way

kəɾke nikəɾ gəⁱle.

doing out went

Sentence 7:

əᵘɾ dʒɐⁱ dʒɐⁱ d̪ʰiɾe d̪ʰiɾe d̪ʰiɾe d̪ʰiɾe dʒə pə̃ᵘtʃele huã dʒõᵘɽəha and going.going slowly.slowly.slowly.slowly we reached had Jauraha

nɐlɐ t̪o huã pəɾ ek d̪ui d̪ãᵘ pəⁱhle bəgʈa dʒon he ghds kʰɐʈe creek had at one two times before tiger had grass cutting

ʋeɾi bʰəɾd̪ɐ pɐkədle ɾəhe. time bulls caught

And as we were going slowly we reached Jauraha creek. Once or twice before, a tiger had caught a bull there during grass cutting time.

Question 2: What had happened once or twice before at Jauraha Nala? Answer 2: A tiger had caught a bull.

Sentence 8:

t̪o hərnɾe d̪əɾɐⁱ e kəõ əⁱsɐ nəõ beki hɐmɾo bəɾd̪a pəkəɖli. (we)our feared that this way our bull will.catch So we feared that this time also a tiger might catch our bull.

Sentence 9:

t̪o həməɾe ek goⁱt̪e ɾəhe bʰəⁱsa əᵘɾ ek goⁱɾəhə bʰəɾd̪ɐ. we.had one was buffalo and one bull We had one buffalo cart and one bullock cart.

Sentence 10:

əu bʰəɾd̪ɐʋɐlɐ ⁱɛjn dʒonɾhe ləɽʰja bʰigədjəl. and bullock.cart cart damaged And the bullock cart was damaged.

Question 3: What happened to the bullock cart? Answer 3: It was damaged.

Sentence 11

t̪o ləɽʰja dʒəb bʰigədjəl t̪o ⁱɛjnet̪e pɐtʃe ɾəhine ɔ həməɾe

cart when damaged behind stayed and we

ɐge tʃəlɪgɪli.

ahead went

When the cart was damaged, it stayed behind and we went ahead.

Sentence 12:

dʒəb ɐge tʃəlɪgɪli t̪o ⁱɛhu log dʒəb bəɖɐ mʊskilse when ahead went these people when great difficulty

ləɽjɐ ʊɽjɐ bənihne.

cart made(repaired)

When we went ahead, they repaired the cart with great difficulty.

Sentence 13:

əᵘ tʃəld̪ene t̪əb ləɽjɐ ɐke gʰəɾ gʰəɾ gʰəɾ gʰəɾ d̪aᵘɾat̪ tʃəld̪ene

and went then cart forward sound.of.running running went Then they made the bullocks run.

Question 5: After they fixed the cart, how did they drive it? Answer 5: They made it run.

Sentence 14:

t̪aᵘ dʒeⁱse həmse həmːəɾ t̪ɪɾ pãᵘtʃne t̪əⁱse ʋahi t̪iɾ ek ɾʊkət like we reached so there one eucalyptus

pẽɖ ɾehẽ.

tree was

They reached us at a eucalyptus tree.

Sentence 15:

t̪o ʋohi t̪iɾ bəkəʈa bʰə6iʈələhe t̪o bəkəʈa dʒon he u t̪ʰuk ləgəⁱl ɾəhe. there tiger was.sitting tiger had was The tiger was sitting and waiting for prey.

Question 6: What was the tiger doing? Answer 6: Waiting for prey.

Sentence 16:

dʒeⁱse vo lɔɽje pãᵘtʃel t̪əⁱse ek d̪ʰəⁱnɐ bəɾt̪əl pəkəɽleh. like(just.as) that cart reached then one right.side bull caught Just as that cart reached the tree, it caught the bull on the right side.

Question 7: When the cart reached the tree, what did the tiger do? Answer 7: It caught one bull.

Sentence 17:

dʒəb d̪ʰəinɐ bəɾt̪əl pəkəɽ lehəl t̪o həmɾe t̪o həm:əɾ bʰə̃ⁱsət̪

then right.side bull caught had we(our) our buffalo

pɛⁱhle d̪aᵘlət̪ pʰɐdʒgijni.

before ran.away

When the right bull was caught, our buffaloes ran ahead.

Question 8: When the tiger caught the bull what did the buffaloes do? Answer 8: They ran away.

Sentence 18:

dʒəb pʰɐdʒgijnu t̪o həməɾe tʃilːɐ ləgɪli ho hu ho hu ɔu ɛnt̪i then ran.ahead we shouted sound.of.shouting and what

kəjɐɾe kɐ huⁱgəl kɐ huⁱgəl.

to.do what happened what happened