Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:03

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Propensity of University Students in the Region of

Antofagasta, Chile to Create Enterprise

Gianni Romaní , Simone Didonet , Sue-Hellen Contuliano & Rodrigo Portilla

To cite this article: Gianni Romaní , Simone Didonet , Sue-Hellen Contuliano &

Rodrigo Portilla (2013) Propensity of University Students in the Region of Antofagasta, Chile to Create Enterprise, Journal of Education for Business, 88:5, 253-264, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.690353

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.690353

Published online: 06 Jun 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 56

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.690353

Propensity of University Students in the Region

of Antofagasta, Chile to Create Enterprise

Gianni Roman´ı

Universidad Cat´olica del Norte, Antofagasta, Chile

Simone Didonet

Universidade Federal do Paran´a, Curitiba, Brazil

Sue-Hellen Contuliano and Rodrigo Portilla

Universidad Cat´olica del Norte, Antofagasta, ChileThe authors aim to discuss the propensity or intention to create enterprise among university students in the region of Antofagasta, Chile, and to analyze the factors that influence the step from desire to intention. 681 students were surveyed. The data were analyzed by binary logistical regression. The results show that curriculum is among the variables that have a positive influence, while the desire for a high level of income and escaping unemployment has a negative influence on the intention. Also, being a woman has a negative influence on the intention to create enterprise. Some gender differences are discussed in this context.

Keywords: entrepreneurship, new business creation, university students

INTRODUCTION

When entrepreneurial attitudes, activities and aspirations in-teract to result in a new enterprise, this has a positive impact on the gross domestic product (GDP) of the region where it is developed due to the creation of jobs and wealth. For this reason, public and private institutions began to concern themselves with creating programs to encourage and sup-port the creation of enterprises as an aspect necessary for development (Katz, 2003).

Furthermore, universities began to participate in this area over 50 years ago, starting with the implementation of pro-grams oriented toward the development of an entrepreneurial culture in students (Katz, 2003). These institutions under-stood that the formation of entrepreneurs is important for

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and the Vicerrector´ıa de Investigaci´on y Desarrollo Tec-nol´ogico VRIDT of the Universidad Cat´olica del Norte for their support.

Correspondence should be addressed to Simone Didonet, Universidade Federal do Paran´a, Department of Administration, Avenida Loth´ario Meiss-ner, 632—Campus Jardim Botˆanico, Curitiba 80210-170, Brazil. E-mail: simonedidonet@ufpr.br

the development of society as a whole, so it should not be taught only in business schools but rather should transverse the entire University (Gibb, 2002). While the first universi-ties to incorporate entrepreneurship in their curriculum were from United States and Europe, in recent years Latin Amer-ican universities have also done so. In Chile, some univer-sities have implemented entrepreneurship courses, forming alliances with universities from United States and Europe. Others universities have created entrepreneurship centers or programs in order to incorporate an entrepreneurial culture in their institutions.

In the region of Antofagasta, situated in northern Chile, there are seven universities, five of them private, one public, and the other public–private. These universities have approx-imately 16,863 students and only two universities are known to have incorporated the subject of entrepreneurship. Both universities started these initiatives in order to encourage an entrepreneurial spirit in the students, not just for the creation of enterprises but also as an attitude of life.

In this sense, this article aims to measure the propensity of university students in the region of Antofagasta, Chile, to cre-ate enterprises.Propensityis defined as the intention to cre-ate enterprises, that is, to have the business idea completed, with or without start-up. Different authors such as D´ıaz,

Hern´andez, and Barata (2004) and Espi, Arana, Saizarbitoria, and Gonz´alez (2007) considered that the propensity to cre-ate enterprises is part of the entrepreneurial potential model proposed by Krueger and Brazeal (1994), composed of three states: the perceived desirability, the perceived viability, and the entrepreneurial intention or propensity. Based on these aspects, this article intends to respond to the following con-cerns: What is the propensity of the university students from the region of Antofagasta to create enterprises? Which fac-tors have the most influence on students to move from the desire to the intention to create an enterprise?

For this purpose, a questionnaire was applied to 681 stu-dents obtained from a stratified probabilistic sample, using as a reference the questionnaire utilized by the Zentrum f¨ur Mittelstands und Gr¨undungs¨okonomie, Kaiserslautern-Zweibr¨ucken-Ludwigshafen Institute in Germany.

This article is divided in the following parts: in the next section we provide the context of entrepreneurial activity in the region. Following that, the theoretical framework and the hypotheses of the research are presented, followed by the methodology used. Next is the presentation and discussion of the results. In the final section, we discuss the implications of this study for firms, as well as the conclusions and limitations of the study.

ENTREPRENEURIAL ACTIVITY IN THE REGION OF ANTOFAGASTA

The region of Antofagasta has a population of approximately 350,000 inhabitants (Instituto Nacional de Estad´ısticas, 2009). This region is characterized by its strong special-ization in the exploitation of natural resources, especially minerals. It is one of the world’s principal copper producers and has historically been considered to be the mining capital of Chile. Despite its strong specialization in mining, around 60% of its GDP, there is a strong entrepreneurial dynamism in the region.

The fact that rates of entry and exit of new enterprises are higher than the national average reflects this dynamic character (Roman´ı, 2009). Furthermore, population growth and increased demand in sectors such as construction, trans-port and communications in recent years are imtrans-portant and favorable factors in the creation of new enterprises in the region. The strong participation of small and medium-sized enterprises in these sectors within the region (Roman´ı, 2009) shows the potential of the region for enterprises and the de-velopment of the country.

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report for the region (Roman´ı & Atienza, 2011) shows that 14.3% of adult population between the ages of 18 and 64 are involved in entrepreneurial activities with up to three and a half years of activity. Only 10.3% of this group of entrepreneurs are between 18 and 24 years old, and 33.8% are between 25 and 34 years old. Among the entrepreneurs in the initial stages (up

to three and a half years of activity), only 5.1% are students and 9.2% have university education. The GEM report for the region also analyzes the local context based on the percep-tions of experts who are involved in entrepreneurial activity. The results show that education and training in entrepreneur-ship was one of the dimensions with the worst evaluations (Roman´ı & Atienza, 2011). The experts also have a nega-tive perception of elementary and secondary education in the region because they believe that it does not stimulate cre-ativity, autonomy, or personal initiative and does not give adequate emphasis to entrepreneurship and the creation of enterprises. These results contribute to reinforce the initial research question: What is the propensity of university stu-dents to create enterprises and which factors influence that propensity?

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESES

University Entrepreneurship

Various authors such as Aponte, Urbano, and Veciana (2006), D´ıaz et al. (2004), Esp´ı et al. (2007), Mayer (2010), Toledano (2006), and Veciana, Aponte, and Urbano (2005), among others, have worked on the subject of creation of enterprises, focusing their research on university students, based on an analysis of their attitudes toward entrepreneurship and which environmental factors influence these attitudes.

Veciana et al. (2005) analyzed the formal and informal institutional factors that influence the creation of enterprises, in addition to studying the perception of entrepreneurs as to the desirability, viability and intention of creating an enterprise. Esp´ıritu and Sastre (2007) analyzed the char-acteristics that have a positive influence on the university students’ entrepreneurial intentions, considering personal-ity traits, values, sociodemographic factors, and academic preparation. Along these same lines, Skudiene, Auruske-viciene, and Pundziene (2010) analyzed psychological and nonpsychological characteristics as well as environmental factors that influenced the entrepreneurial intentions of stu-dents of the faculty of business in Lithuania. The results show that both personal factors and the context influence the stu-dents’ entrepreneurial intentions, with that information also serving as support in designing programs of education in en-trepreneurship. In a similar manner, Mayer (2010) performed a review of the current state of preparation and support from universities for the creation of enterprises, focusing directly on higher education in Mexico, trying to identify charac-teristics and factors appropriate for an integrating plan, de-veloping an efficient program of institutional incentives in universities.

According to Esp´ı et al. (2007), higher education institu-tions have an important role in encouraging entrepreneurship in students. In their research they also prepared a profile of

the entrepreneurial student, and identified various focuses, based mainly on psychological and social-institutional fo-cuses. Toledano (2006) studied the attitudes regarding cre-ating a new enterprise in young people in the university in Huelva (Spain), and tried to prove whether there are relation-ships between these attitudes and the factors that have been most used to explain entrepreneurial behavior.

Other authors have analyzed the topic of entrepreneur-ship and the creation of enterprises by university students in different geographical areas. This is the case of D´ıaz et al. (2004), who analyzed the different attitudes of students in the Universities of Beira (Portugal) and Extremadura (Spain) regarding the creation of enterprises, through perceptions of the desirability, viability, and intention to create an enterprise. Likewise, Aponte et al. (2006) analyzed attitudes toward the creation of enterprises among students of the universities of Catalonia (Spain) and Puerto Rico.

In Chile, studies on university entrepreneurship are scarce and recent. Among them, we can point out Morales, Laroche, and Sarah (2009), who analyzed the influence that the univer-sity environment has on the intention to create enterprises in four universities in Santiago, Chile, and concluded that the faculty’s entrepreneurial climate had a direct influence on the students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Landerretche, Flo-res, and S´anchez (2011) analyzed the individuals’ charac-teristics and competencies that influenced their likelihood to create enterprises. The authors show that experience in the labor market and the degree of risk aversion are significant variables in explaining entrepreneurship.

The majority of the previously mentioned studies use as theoretical support Shapero’s (1982) entrepreneurial event model, Ajzen’s (1991) planned behavior theory, and Krueger and Brazeal’s (1994) entrepreneurial potential model, on which this article is based.

Krueger and Brazeal’s Entrepreneurial Potential Model

Kruegel and Brazeal (1994) developed the entrepreneurial potential model from a social-psychological perspective, based on the planned behavior theory of Ajzen (1991) and the entrepreneurial event model of Shapero (1982). The model points out that the beliefs and attitudes of potential en-trepreneurs depend on their perceptions and suggest three critical constructs: perceived desirability, perceived feasibil-ity, and the propensity to act.

Perceived desirability, defined as the attraction to creating enterprises, involves two components from Ajzen’s (1991) planned conduct theory: the attitude toward the creation of enterprises and social norms.

Attitude is influenced by the individual’s perceptions of what is considered desirable and is related to intrinsic in-terests and motivations, as well as incentives or disincen-tives. In this regard, the conceptual model of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor identifies needs and opportunities

as the principal motivators of entrepreneurship. Need is de-fined as survival and opportunity as being able to increase income or to be independent. There are persons who have difficulty in accepting rigid organizations and are contrary to command hierarchies; therefore they may wish to be inde-pendent to make their own decisions, indeinde-pendent of other people’s opinions (Douglas & Shepherd, 2002), as well as to have financial independence (Skudiene et al., 2010).

In the case of university students, the desirability to be their own boss, carry out their own ideas, or escape unem-ployment can be important intrinsic motives in their propen-sity to create enterprises, as well as incentives that they con-sider desirable to receive from their university in terms of training, seminars on business plans, contacts with compa-nies, the initial financial push, and the university office of support and the incubator. Consequently, the following hy-potheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Personal desirability would positively

influence the intention to create enterprises.

H2: The desirability for support from the university would

positively influence the intention to create enterprises.

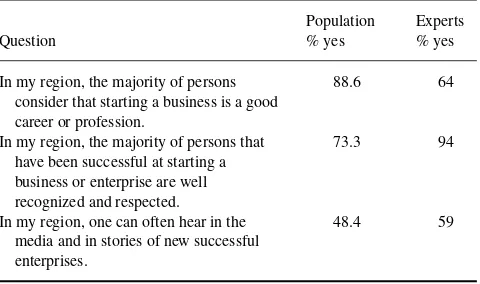

Social norms are related to people’s perceptions regard-ing the creation of enterprises, that is, whether community institutions or leaders actually approve of self-employment. According to Roman´ı and Atienza (2011), the perceptions of the adult population, understood as all the members of the regional community between 18 and 64 years old, as well as those of experts in the region (academics, policy makers, entrepreneurs, and managers directly or indirectly involved in entrepreneurial activities), about the values of being en-trepreneurs are favorable. The majority of respondents con-sidered the region as a favorable space for entrepreneurial ac-tivity. There is a strong social recognition of entrepreneurial activity and it is considered that starting a business is a good career or profession (see Table 1).

In the case of university students it is important to know the students’ perception of their university regarding the

TABLE 1

Perceptions About the Value of Being an Entrepreneur

Question

Population % yes

Experts % yes

In my region, the majority of persons consider that starting a business is a good career or profession.

88.6 64

In my region, the majority of persons that have been successful at starting a business or enterprise are well recognized and respected.

73.3 94

In my region, one can often hear in the media and in stories of new successful enterprises.

48.4 59

Source:Roman´ı and Atienza (2011).

creation of enterprises. Studies show that the university has an increasingly dynamic role in supporting entrepreneurial initiatives (Katz, 2003) and the amount of research on the characteristics of what are currently known as entrepreneurial universities has increased (Etzkowitz, 2004). From that, the following hypothesis emerged:

H3: The students’ perception of their faculty or university

would positively influence their intentions to create en-terprise.

The perceived feasibility or perceived self-sufficiency is the person’s perceived ability to carry out some desired con-duct, in this case the propensity to create an enterprise. On this point it is important that the obstacles perceived do not affect their intention to create enterprises. In this regard, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H4: The perceived difficulties would negatively influence the

intention to create enterprises.

Attitude toward risk is another variable that influences the intention to create enterprises. Esp´ıritu and Sastre (2007) demonstrated that risk is a significant variable that explains university students’ entrepreneurial attitude. From that the following hypothesis arose:

H5: A fearful attitude toward risk would have a negative

relationship with the intention to create enterprises.

Knowing entrepreneurs or having a person close who is an entrepreneur is positive in the intention to create an terprise. Leiva (2004) showed that a good portion of en-trepreneurs (between 40% and 60%) tend to descend from families in which some of their members are self-employed or entrepreneurs. In other studies it has been proven that persons surveyed whose parents were small business owners show a greater preference for self-employment than to be an employee of a large company (Crant, 1996; Rubio, Cord´on, & Agote, 1999; Scott & Twomey, 1988). Based on this, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H6: Students who have an entrepreneur in their close

envi-ronment would be positively related to the intention to create an enterprise.

Finally, it has been considered interesting to incorporate the sex variable in the research model because there are studies on university students and the creation of enterprises that show the existence of a significant presence of more men than women students with the intention to create enterprises (Rodriguez & Prieto, 2009, Rubio et al., 1999). Therefore, the following hypothesis emerged:

H7: The male sex would positively influence the intentions

of students to create an enterprise.

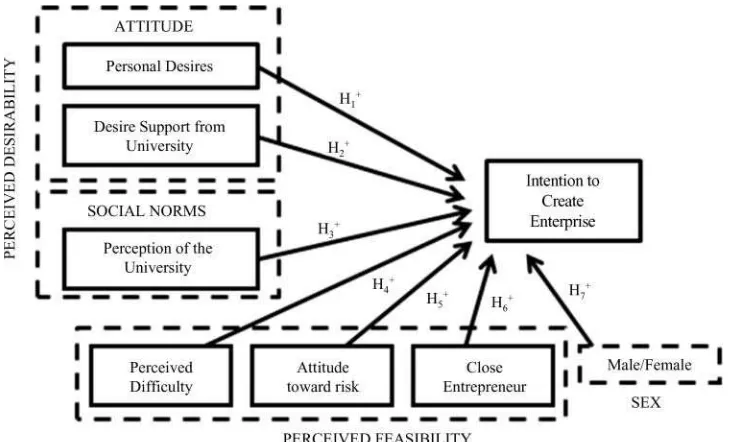

Figure 1 summarizes the model used to test the hypothe-ses, adapted from Kruegel and Brazeal (1994).

METHOD

Sample Selection

In the region of Antofagasta there are seven universities, four of which agreed to participate in this study. These four uni-versities are located in the regional capital (Antofagasta) and house a total of approximately 13,858 students. The type of sampling used was stratified probabilistic with proportional fixation, which resulted in a total of 692 students with a 5% margin of error.

The instrument used to collect the data was a question-naire with 25 questions, of which 21 are multiple choices and four have 4-point Likert-type scales. The questions in-clude the student’s sociodemographic aspects, risk aversion, knowing an entrepreneur, the desire and intention to create an enterprise, the reasons for creating an enterprise, and the perceived difficulties and perceptions on the preparation to be received and the university climate, among others.

The survey was taken of the entire sample selected be-tween August and September 2010. A total of 681 valid cases were obtained. Of a total of 681 valid surveys, 520 students expressed the desire to create an enterprise and this was the final sample considered for analysis in this article. The average age of these students was 22.28 years (SD = 2.325), with the minimum being 18 years and the maximum 30 years; 56% of these 520 students were men and 44% were women. Furthermore, 128 students stated that they had the intention, that is, they had a completed business idea. This percentage was higher than that obtained by Ruda, Martin, Ascua, and Danko (2008) of students in Germany where only 11% of 780 students had the intention to create an enterprise (using the same type of questionnaire). Among the students that showed interest in creating a business, 29% indicated that desire to start a business in the service sector to final con-sumers (retail), 11% chose the primary sector, 12% chose the transformation sector, and 28% chose other sectors.

Selection of Variables

The Appendix summarizes the variables used in the model referred to in Figure 1. The Appendix shows the variables, the scale used for measurement and the transformation criteria for analyzing the data. In total, 31 variables were considered in the analysis, representing the dimensions studied. As pre-viously mentioned, the constructs, dimensions, subdimen-sions and variables were adapted from the Entrepreneurial Potential Model (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994).

As can be seen in the Appendix, the constructs consid-ered for the analysis are the perceived desirability and the perceived feasibility. For the first construct, the dimensions of attitude and social norms were analyzed, with their re-spective subdimensions that include personal desirability, the desire for support from the university, and perception of the university. With regard to the perceived feasibility construct

FIGURE 1 Model for testing the hypotheses.Source:Adapted from Krueger and Brazeal (1994).

the dimensions considered were the perceived difficulties, attitude toward risk, and having an entrepreneur close. The sex was considered as a separate dimension.

Data Analysis Technique

Because the objective of the study was to identify the factors that influence the step from the desire to the intention to create an enterprise, a binomial logistical regression has been used, through the Enter method, characterized by the introduction of all variables at the same time, without a sequence for introducing them.

Prior to the regression, the reliability of the data collection instrument was estimated by means of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, obtaining an alpha of .661. A Pearson correla-tion analysis was also performed, which enabled eliminating variables with correlations of over .5.

Following the logistical regression, and with the objective of deepening understanding of the results associated with gender, two linear regressions were developed to identify the similarities and differences between men and women in the propensity to create enterprises. To do this, the sample was divided into two groups according to the sex of the students. A linear regression was carried out, using the entrepreneurial propensity of students as a dependent variable and the vari-ables defined in the Appendix as independent varivari-ables. This analysis considered the original scale for both the dependent and independent variables.

RESULTS

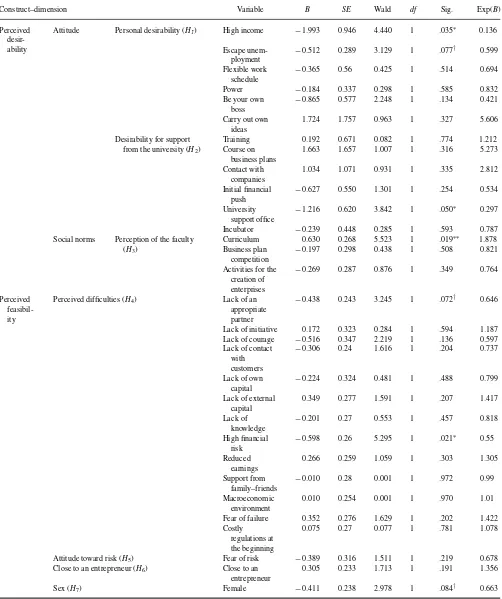

Table 2 shows the results of the binary logistical regres-sion used in testing the hypotheses. According to the results,

the model shows a likelihood log of –502,978 (Nagelkerke

R2 =.206; omnibus tests of model coefficients p =.000;

Hosmer-Lemeshow testp=.673) indicating that the model is statistically significant. Furthermore, the model is able to correctly classify 77.7% of the cases with 99% significance. According to the results presented in Table 2, not all the variables are significant in the model and the large majority of those that are significant show negative coefficients. The following section is a discussion of the results associated with the hypotheses that were tested and the dimensions studied.

Factors Linked to Perceived Desirability

In terms of personal desirability (H1), the variable high

in-come is significant in the model, with apvalue<01,

how-ever, it has a negative coefficient. That is, this motivation in the students negatively affects their intention to create an enterprise. This result is strange because according to other studies such as the GEM, the reasons a person starts an en-terprise are mainly need and opportunity, the latter defined as increasing income or being independent.

It seems that this motivation is not the reason that moves students from the desire to the intention to create an enter-prise, that is, having the business idea completed. In other studies, however, this variable is statistically significant to explain the intention to create an enterprise (Skudiene et al., 2010).

Another variable that has turned out to be significant, with ap<.05 is escaping unemployment. As in the previous case,

strangely to what is expected, this variable has a negative co-efficient. In general, the motivation to create an enterprise in order to escape unemployment is generally associated with entrepreneurship based on need, where entrepreneurship

TABLE 2

Results of Students’ Intentions to Create Enterprise

Construct–dimension Variable B SE Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

Perceived desir-ability

Attitude Personal desirability (H1) High income −1.993 0.946 4.440 1 .035∗ 0.136

Escape unem-ployment

−0.512 0.289 3.129 1 .077† 0.599

Flexible work schedule

−0.365 0.56 0.425 1 .514 0.694

Power −0.184 0.337 0.298 1 .585 0.832

Be your own boss

−0.865 0.577 2.248 1 .134 0.421

Carry out own ideas

1.724 1.757 0.963 1 .327 5.606

Desirability for support from the university (H2)

Training 0.192 0.671 0.082 1 .774 1.212 Course on

business plans

1.663 1.657 1.007 1 .316 5.273

Contact with companies

1.034 1.071 0.931 1 .335 2.812

Initial financial push

−0.627 0.550 1.301 1 .254 0.534

University support office

−1.216 0.620 3.842 1 .050∗ 0.297

Incubator −0.239 0.448 0.285 1 .593 0.787

Social norms Perception of the faculty (H3)

Curriculum 0.630 0.268 5.523 1 .019∗∗ 1.878

Business plan competition

−0.197 0.298 0.438 1 .508 0.821

Activities for the creation of enterprises

−0.269 0.287 0.876 1 .349 0.764

Perceived feasibil-ity

Perceived difficulties (H4) Lack of an appropriate partner

−0.438 0.243 3.245 1 .072† 0.646

Lack of initiative 0.172 0.323 0.284 1 .594 1.187 Lack of courage −0.516 0.347 2.219 1 .136 0.597 Lack of contact

with customers

−0.306 0.24 1.616 1 .204 0.737

Lack of own capital

−0.224 0.324 0.481 1 .488 0.799

Lack of external capital

0.349 0.277 1.591 1 .207 1.417

Lack of knowledge

−0.201 0.27 0.553 1 .457 0.818

High financial risk

−0.598 0.26 5.295 1 .021∗ 0.55

Reduced earnings

0.266 0.259 1.059 1 .303 1.305

Support from family–friends

−0.010 0.28 0.001 1 .972 0.99

Macroeconomic environment

0.010 0.254 0.001 1 .970 1.01

Fear of failure 0.352 0.276 1.629 1 .202 1.422 Costly

regulations at the beginning

0.075 0.27 0.077 1 .781 1.078

Attitude toward risk (H5) Fear of risk −0.389 0.316 1.511 1 .219 0.678

Close to an entrepreneur (H6) Close to an entrepreneur

0.305 0.233 1.713 1 .191 1.356

Sex (H7) Female −0.411 0.238 2.978 1 .084† 0.663

†p<.10.∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.

becomes a way of survival. These results lead to partially re-jectH1.

In the dimension desirability for support from the univer-sity (H2), one of the variables that influences the intention

of university students in the region to create an enterprise is the University Support Office. Even though this variable is 95% significant (p <.05), it has a negative coefficient,

in the contrary to what expected. It seems that the existence of a university office to support entrepreneurship does not influence students in their intention to create enterprises. These results lead to partially rejectH2.

The results of this group of variables related to the support expected from their university could show that they probably do not exist in the universities. Because they do not exist the students do not have a sense of the dimension this support provides. It is important to mention that only two of the four universities that participated in the study have units that have carried out some activities to encourage entrepreneurship and it is known that this does not extend across the entire univer-sity, so it is possible that many of the students are not aware of these units. It is here where an opportunity opens up, and, at the same time, a challenge for regional universities: to im-plement programs oriented toward the creation of enterprises that cross over all the courses of study.

In terms of the dimension perception of the faculty (H3),

the variable that explains the intention to create an enter-prise is the curriculum, with 95% significance (p < .05).

This is an interesting result for the university faculties to take into consideration when designing their programs of study. If the university is interested in encouraging university en-trepreneurship, it should orient and restructure its curriculum, emphasizing the creation of enterprises and the development of an entrepreneurial spirit. As noted by Hazeldine and Miles (2007), the entrepreneurship has to be encouraged by deans who “must reassess the school’s mission, reward and support opportunity creation and discovery” (p. 234).

The other variables in this group have not turned out to be statistically significant. Therefore,H3is partially accepted.

Factors Linked to Perceived Feasibility

In the dimension perceived difficulties (H4), the statistically

significant variables with ap<.1 and<.05 are the lack of an

appropriate partner and the high financial risk, respectively. These variables negatively influence the students’ intention to create enterprises, thereforeH4is partially accepted.

The lack of an appropriate partner was expected, as au-thors such as Timmons and Spinnelli (2007) and Abrams (2010), show that the team is the key to the success of a business. The importance of having an appropriate partner is paramount when creating an enterprise. Furthermore, the fact that students perceive that their high own financial risk is a difficulty that could limit their intention to create an enter-prise shows their concern with financing. Access to financ-ing is key when creatfinanc-ing an enterprise and that in the initial

TABLE 3

Total 520 100 128 100 25

stages entrepreneurs have difficulties in accessing traditional sources of financing (banks). So this result is consistent with expectations.

The attitude toward risk is not statistically significant in this model, in contrast to previous studies such as that by Esp´ıritu and Sastre (2007). Therefore, we rejectH5.

Knowing or having someone close who is an entrepreneur has not turned out to be statistically significant, despite hav-ing a positive sign. This variable does not influence the likeli-hood that a student has the intention to create an enterprise or has the business idea completed, so hypothesisH6is rejected.

These results differ from others such as Leiva (2004) and Rubio et al. (1999), who showed that having someone close who is an entrepreneur does influence the intention to create an enterprise.

Sex (H7)

Sex is another of the variables that has turned out to be significant (p<.1) with a negative coefficient. Considering

that female was the tested variable in the model, it can be said that being a woman negatively influences the intention to create an enterprise and consequently, the influence of men is positive, which leads to accepting hypothesis H7. This

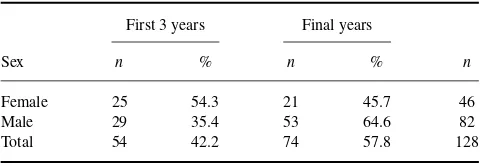

result was expected since in analyzing the sample of students who had the desire versus the students who had the business idea completed, it was seen that the percentages of women decreased by 8% from the desire to the intention, while in the case of men increased in 8% (Table 3).

These results coincide with those obtained by Esp´ıritu and Sastre (2007) and Rubio et al. (1999), who showed a higher desire and intention to create an enterprise in men student than in women. These results are also similar to D´ıaz et al. (2004) who found that gender affects the students’ intention,

TABLE 4

Influence of Years at University and Sex on the Intention to Create a Business

First 3 years Final years

Sex n % n % n

Female 25 54.3 21 45.7 46

Male 29 35.4 53 64.6 82

Total 54 42.2 74 57.8 128

TABLE 5

Gender Comparison for Intention to Create Enterprise

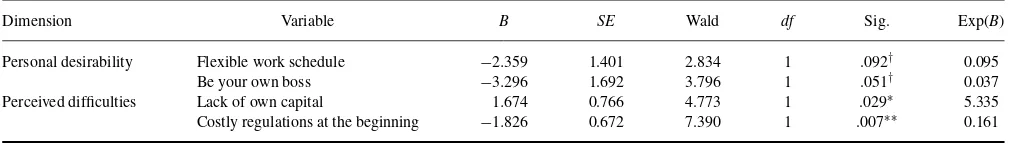

Dimension Variable B SE Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

Personal desirability Flexible work schedule −2.359 1.401 2.834 1 .092† 0.095

Be your own boss −3.296 1.692 3.796 1 .051† 0.037

Perceived difficulties Lack of own capital 1.674 0.766 4.773 1 .029∗ 5.335

Costly regulations at the beginning −1.826 0.672 7.390 1 .007∗∗ 0.161

Note. N=128. Women coded as 0, men coded as 1.

†p

<.10.∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.

and are in contrast to the study developed by Shinnar, Pruett, and Toney (2009), who identified no differences between male and female students regarding interest in entrepreneur-ship.

In terms of the number of years at university and the intention of student to create a business, 54.3% of women in the first years of university stated having the intention of starting a business, in contrast to 64.6% of men in their last years of university (see Table 4).

Deepening the comparison of men and women in the stage of intention, Table 5 shows the gender differences in terms of factors that affect this phase of the propensity to create a business. To do this, we considered only the group of students with the intention of starting a business (128 in total). Gender was taken as a dependent variable in a new logistical regres-sion model (male coded as 1, female coded as 0). According to the results, the model shows a likelihood log of –114.887 (NagelkerkeR2=.460; omnibus tests of model coefficients

p =.005; Hosmer-Lemeshowp=.640) indicating that the model is statistically significant. Furthermore, the model was able to correctly classify 73.4% of the cases. Table 5 shows only the significant results of the model.

Of the four significant factors (see Table 5), two are re-lated to personal ambitions and the other two to perceived difficulties. In terms of personal ambition, the results indi-cate that variable flexible work schedule negatively affects men in their intention to create a business, in contrast to women. Thepof .092 and the coefficient of –2.359 indicate that the more flexible the work schedule, the less the inten-tion among men to start a business. In contrast, the desire for a flexible schedule is favorable for women. Another factor that negatively affects men is be your own boss (p=.051, coefficient=–3.296). In effect personal desirability for an individual to be his or her own boss is not a factor that leads men to start a business, while it is for women. In terms of perceived difficulties, the lack of capital is positively related among men to the intention to start a business. Thepof .029 and the positive coefficient of 1.674 reveal that this is not a difficulty as perceived by men in their intention to create a business. Compared to women, men do not consider the lack of capital as a limiting factor in starting a business. In con-trast, the costly regulations at the beginning show a strong and negative relationship among men with the intention to

start a business, in contrast to women (p=.007, coefficient

=–1.826). Thus, the more costly the regulations at the begin-ning of creating enterprise, fewer men will have the intention of starting a business.

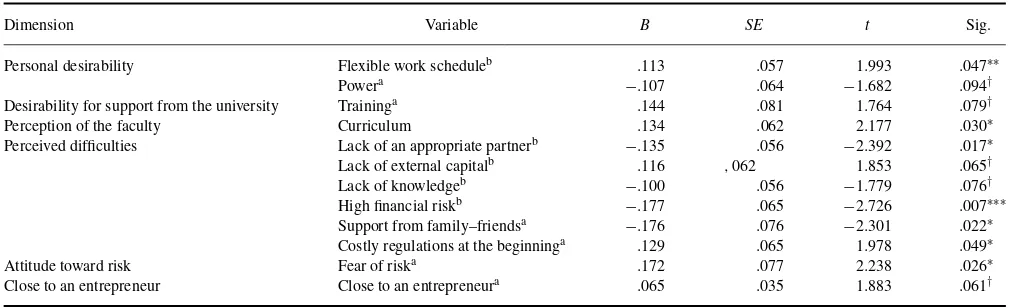

The variables flexible work schedule and costly regula-tions at the beginning are also factors positively or negatively associated with the propensity to create enterprises, consid-ering the step from the desire to intention, in function of gender. Table 6 shows the results of the two linear regres-sions developed at this stage, considering the samplings of men and women. For the group of women, the significance of the model was .038 (R2=.191,SE=.723),F=1.566, and

for the men the significance was .001 (R2=.200,SE=.729),

F=2.164. The results shown only consider the significant variables in the model.

According to the results shown in Table 6, men and women receive different influences on their propensity to create en-terprises. In the case of women, the training they received from the faculty (p=.079, coefficient=0.144) and the in-fluence of entrepreneurs close by (p =.065, coefficient=

0.065) are factors that favor their propensity to create enter-prises. As well, the more risky the enterprise (less fear of risk), the greater the entrepreneurial propensity of women. The p of .026 and the coefficient of 0.172 for fear of risk confirm that there is a significant and positive relationship between the two variables. Likewise, women do not see the costly regulations to start a business as a difficulty. The re-sults in Table 6 show that this variable positively influences the propensity to create enterprises (p = .049, coefficient

=0.172). On the other hand, the support from family and friends has a significant and negative relationship with en-trepreneurial propensity among women (p=.022, coefficient

= −0.176), which indicates that the greater the support of groups close to women, the lower their propensity to start a business. This contrasts with previous result of knowing an entrepreneur, which indicates that while women are not favored by the support provided by their families or friends, it is important to have the benefit of the tacit experience and knowledge of entrepreneurs who are close to them. Finally, women do not seek power in through their entrepreneurial propensity, that is to say, they do not see creating a business as a way to having power. According to the result shown in Table 6, there is a significant and negative relationship

TABLE 6

Gender Differences for Propensity to Create Enterprise

Dimension Variable B SE t Sig.

Personal desirability Flexible work scheduleb .113 .057 1.993 .047∗∗

Powera −.107 .064 −1.682 .094†

Desirability for support from the university Traininga .144 .081 1.764 .079†

Perception of the faculty Curriculum .134 .062 2.177 .030∗

Perceived difficulties Lack of an appropriate partnerb −.135 .056 −2.392 .017∗ Lack of external capitalb .116 ,062 1.853 .065†

Lack of knowledgeb −.100 .056 −1.779 .076†

High financial riskb −.177 .065 −2.726 .007∗∗∗ Support from family–friendsa −.176 .076 −2.301 .022∗ Costly regulations at the beginninga .129 .065 1.978 .049∗

Attitude toward risk Fear of riska .172 .077 2.238 .026∗

Close to an entrepreneur Close to an entrepreneura .065 .035 1.883 .061†

Note.n=230 (women),n=290 (men). Dependent variable=propensity to create an enterprise. aResult for women.bResult for men.

†p<.10.∗p<.05.∗∗∗p<.001.

between power and entrepreneurial propensity among women (p=.094, coefficient= −0.107).

In relation to men, the result in Table 6 reveals that the goal of having flexible work schedules is a factor that positively influences the propensity of men to create an enterprise, with a significance of 95% (p =.047, coefficient = 0.113). In effect, the greater the desire for a flexible work schedule, the greater the propensity among men to start business. As the well, the training received by the faculty (curriculum) is important to the propensity to create a business. The p of .030 and the positive coefficient of 0.134 confirm with 95% confidence that the better the training received in the fac-ulty, the more men will have a propensity to start a business. In relation to the perceived difficulties, the lack of exter-nal capital is a factor positively associated among men with the propensity to create a business (p=.065, coefficient=

0.116). Despite the relatively low significance (90%), the re-sult indicates that, upon deciding to create a business, men do not fear that the lack of external capital will be a limiting factor to initiate the business. On the other hand, men do perceive as difficulties: the lack of an appropriate partner (p

=.017, coefficient=–0.135), the lack of knowledge (p=

.076, coefficient =–0.100), and the high financial risk (p

=.007, coefficient=–0.177). The latter difficulty confirms with 99% confidence that men fear assuming the financial risks of starting a business. This result was also found in the analysis for the total sample (see Table 2) and confirms the concern of the students about the financing of their future enterprises.

In general, results evidence the strong presence of social roles and how they influence the conditions for the creation and development of enterprises managed and directed by women. Even though in recent years there has been a greater participation by women in all fields, including the creation of enterprises, not only in Chile but worldwide (Hausmann et al., 2010), the male presence is still compelling in the area of intending to create enterprises.

This could be explained with the theory of investment in roles, where the family decision implies an exchange of roles represented by each member of the family. Accord-ing to Bielby and Bielby (1988), England (1984), and Lobel (1991), women tend to invest in roles within the home (do-ing domestic work) while men engage in remunerated work. This leads to differences in the specification of roles, which is evidenced in education, the studies women and men pur-sue and consequently their entrepreneurial interests. From this perspective, gender roles are reinforced, serving being considered a feminine characteristic of being closer to the family and community, and making as a masculine charac-teristic associated with the intention to make something for the community (Sheridan, McKenzie, & Still, 2011). Consid-ering the context of the study, the results confirm the influence of gender roles in the entrepreneurial propensity of male and female students.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

The results show that 19% of university students in the re-gion of Antofagasta had the intention to create an enterprise, that is, they have a business idea completed. This result is relatively positive, taking into account that the local context is not inclined toward entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial education has been one of the dimensions most poorly eval-uated by professionals in the regional GEM study (Roman´ı & Atienza, 2011). On the other hand, this result could reflect the perception that the Antofagasta region is a land of op-portunities. According to the result of GEM 2010 (Roman´ı & Atienza, 2011), people in general believe that the region offers opportunities for starting enterprises and that students can be influenced by these perceptions in their propensity to create enterprises. Likewise, population growth, investment in large operations in the region, and increased demand in the

construction, transport, and communications sectors, among other aspects, are factors of a favorable environment for the creation of enterprises. The average rate of entry and exit of new enterprises in the region is higher than the national aver-age, reflecting the dynamic nature of entrepreneurial activity (Roman´ı, 2009).

In regard to the study results and according to the model proposed, the desirability to obtain a high income, escape unemployment, and have a support office are the variables that negatively influence the propensity to create enterprises, while the curriculum has a positive influence. However, these results need to be taken carefully since they contradict the majority of the studies reviewed, in which those variables have been verified as influencing the propensity to create en-terprises. The result regarding the curriculum is interesting because it will enable universities and faculties to improve and reorient their programs of study in favor of entrepreneur-ship.

Regarding to the perceived feasibility, only two variables were statistically significant and with a negative coefficient: the lack of an appropriate partner and the high own finan-cial risk. Therefore, these variables negatively influence the intention to create enterprises, accepting those hypotheses.

The gender variable has turned out to be statistically significant in the students’ intention to create enterprises. According to this result, being a woman negatively influ-ences the propensity to create enterprises. This result is in-teresting because it shows that efforts to encourage female entrepreneurship need to be reinforced. This implies that when universities implement their policies to encourage en-trepreneurship, they need to take the gender dimension into consideration. This includes understanding gender roles and the characteristics of the local environment that encourage or impede the propensity to create enterprises. As highlighted in this study, men and women have different perceptions of en-vironmental factors and are motivated by different objectives in their propensity to create enterprises.

Equally important is the university-industry-government link in encouraging university enterprises. The Triple Helix concept (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 1995) has been used for different purposes, including an operational strategy for re-gional development in countries like Sweden (Jacob, 2006), Malaysia and Algeria (Saad, Zawdie, & Malairaja, 2008). In Brazil it has become a movement to generate incubators within universities (Almeida, 2005) and can be applied to promote university enterprises. Universities in collaboration with enterprises and in alliance with government can encour-age contests for innovative design among university students and workshops on developing business plans, among other activities. Likewise, university collaborations with business, whether by means of knowledge transfer, entrepreneurial training programs, spaces for entrepreneurial practices or other means, can generate a favorable environment for stu-dent entrepreneurship. The university–industry–government link within the region is presently very weak, although

col-laboration is increasing. Nevertheless, the private sector still does not see universities as sources of information, knowl-edge transfer and as active agents in innovation and sustain-able development (Atienza, 2009).

Finally, it is important to point out that this study is a first approximation to understanding the propensity of students in the region of Antofagasta to create enterprises and of the variables that influence that propensity, so the results must be taken with caution. It is necessary to probe into other variables that were not considered in this study, such as the students’ family income and rethinking the model used, given that there are various variables that have not turned out to be significant, even though there is empirical evidence to the contrary, which leads to thinking about a more in-depth review of the variables and the research model used.

REFERENCES

Abrams, R. (2010).The successful business plan: Secrets and strategy(4th ed.). Toronto, Canada: The Planning Shop.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes,50, 179–211.

Almeida, M. (2005). The evolution of the incubator movement in Brazil.

International Journal of Technology and Globalization,1, 258–277.

Aponte, M., Urbano, D., & Veciana, J. M. (2006). Actitudes hacia la creaci´on de empresas: Un estudio comparativo entre Catalunya y Puerto Rico [Atti-tudes toward business creations: A comparative study between Catalonia and Puerto Rico].Forum Empresarial,11(2), 52–75.

Atienza, M. (2009). Pr´acticas de gesti´on y modernizaci´on empresarial de las Pymes de la regi´on de Antofagasta [Management practices and mod-ernization of the SME in the region of Antofagasta]. In M. Atienza (Ed.),

La evoluci´on de la Pyme de la regi´on de Antofagasta[The evolution of

the SME of the region of Antofagasta] (pp. 65–108). Antofagasta, Chile: Ediciones Universitarias, Universidad Cat´olica del Norte.

Bielby, D., & Bielby, W. (1988). She works hard for the money: Household responsibilities and the allocation of work effort.American Journal of

Sociology,93, 1031–1059.

Crant, J. M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of en-trepreneurial intentions.Journal of Small Business Management,34(3), 42–49.

D´ıaz, J. C., Hern´andez, R., & Barata, M. L. (2004). Estudiantes univer-sitarios y creaci´on de empresas. Un an´alisis comparativo entre Espa˜na y Portugal [University students and new venture creation. A com-parative analysis between Spain and Portugal]. Conocimiento,

Inno-vaci´on y Emprendedores: Camino al Futuro, 1338–1355. Retrieved from

http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2234363

Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A, (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions and utility maximization.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,2(3), 81–90.

England, P. (1984). Wage appreciation and depreciation: A test of neoclassi-cal economic explanation of occupational sex segregation.Social Forces, 62, 726–800.

Esp´ı, M. H., Arana, G., Saizarbitoria, I. H., & Gonz´alez, A. (2007). Perfil emprendedor del alumnado universitario del campus de Gipuzkoa de la UPV/EHU [Entrepreneurial profile of university students of Gipuzkoa campus of the UPV/EHU].Revista de Direcci´on y Administraci´on de

Empresas,14, 83–110.

Esp´ıritu, R., & Sastre, M. A. (2007). La actitud emprendedora durante la vida acad´emica de los estudiantes universitarios [Entrepreneurial

attitude during the academic life of the university students].Cuadernos

de Estudios Empresariales,17, 95–116.

Etzkowitz, H. (2004). The evolution of the entrepreneurial university.

Inter-national Journal of Technology and Globalization,1, 64–77.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (1995). The triple helix university-industry-government relations: A laboratory of knowledge-based eco-nomic development.EASST Review,14, 14–19.

Gibb, A. (2002). In pursuit of a new entreprice and entrepreneurship paradigm for learning: Creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combination of knowledge.International Journal

of Management Reviews,4, 233–269.

Hazeldine, M., & Miles, M. (2007). Measuring entrepreneurship in business schools.Journal of Education for Business,82, 234–239.

Instituto Nacional de Estad´ısticas. (2009). Proyecciones de poblaci´on.

Instituto Nacional de Estad´ısticas [Population projections. National

Institute of Statistics.] Retrieved from http://www.ine.cl/canales/chile estadistico/familias/demograficas vitales.php

Jacob, M. (2006). Utilization of social science knowledge in science pol-icy: Systems of Innovation, Triple Helix and VINNOVA.Social Science

Information,45, 431–462.

Katz, J. A. (2003). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education: 1876–1999.Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 283–300.

Krueger, N., & Brazeal, D. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs.Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice,18, 91–104. Landerretche, O., Flores, B., & S´anchez, G. (2011).Propensi´on al

em-prendimiento: ¿Los emprendedores nacen, se educan o se hacen? [Propensity towards entrepreneurship: Are entrepreneurs born, educated or made?] (Working Paper No. 330). Santiago, Chile: Faculty of Eco-nomics and Business, Universidad de Chile.

Leiva, J. C. (2004). Estudio exploratorio de la motivaci´on emprendedora en el ITCR [Exploratory study of the entrepreneurial motivation in the ITCR]. In S. Roig, D. Ribeiro, R. Torcal, A. de la Torre & E. Cerver (Eds.),El emprendedor innovador y la creaci´on de empresas de I+D+i [The innovator entrepreneur and the R+D+i new venture creation] (pp. 323–339). Valencia, Spain: Servei de Publicaci´ons Universitat de Valen-cia.

Lobel, S. (1991). Allocation of Investment in work and family roles: Alter-native theories and implications for research.Academy of Management

Review,16, 507–521.

Mayer, E. L. (2010).El fomento de la creaci´on de empresas desde la Uni-versidad Mexicana. El caso de la UniUni-versidad Aut´onoma en Tamaulipas [The promotion of new venture creation from the Mexican university: The case of the autonomous university in Tamaulipas]. (Doctoral dissertation.) Universit´a Aut´onoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Morales, M., Laroche, D., & Sarah, F. (2009, November).El Clima de Em-prendimiento, un determinante clave en la intenci´on emprendedora de los

estudiantes de Escuelas de Negocio[The entrepreneurship environment,

a key determinant in the entrepreneurial intention of the business school’s students]. Paper presented at the XLIV Annual Meeting CLADEA 2009 Proceedings, Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Rodriguez, C. A., & Prieto, F. A. (2009). La sensibilidad al emprendimiento en los estudiantes universitarios. Estudio Comparativo Colombia-Francia [A comparative study of sensitivity to entrepreneurship in Colombian and French university students].Innovar,19(1), 73–89.

Roman´ı, G. (2009). La Pyme en Chile [The SME in Chile]. In M. Atienza (Ed.),La evoluci´on de la Pyme de la regi´on de Antofagasta. Centro de

Emprendimiento y de la Pyme[The evolution of the SME of the

Antofa-gasta region] (pp. 9–26). AntofaAntofa-gasta, Chile: Ediciones Universitarias, Universidad Cat´olica del Norte.

Roman´ı, G., & Atienza, M. (2011).GEM Informe de la Regi´on de

Antofa-gasta, Chile 2010[GEM Antofagasta region, Chile report 2010].

Antofa-gasta, Chile: Ediciones Universitarias, Universidad Cat´olica del Norte. Rubio, E. A., Cord´on, E., & Agote, A. L. (1999). Actitudes hacia la creaci´on

de empresas: Un modelo explicativo [Attitudes toward new ventures cre-ation: An explanatory model].Revista Europea de Direcci´on y Econom´ıa

de la Empresa. 8(3), 37–52.

Ruda, W., Martin, T., Ascua, R., & Danko, B. (2008, June).Foundation

propensity and entrepreneurship characteristics of students in Germany.

Paper presented at the 53rd ICSB World Conference, Halifax, Canada. Saad, M., Zawdie, G., & Malairaja, C. (2008). The triple helix strategy

for universities in developing countries: the experience of Malaysia and Algeria.Science and Public Policy,35, 431–443.

Scott, M., & Twomey, F. (1988). The long-term supply of entrepreneurs: Students’ career aspirations in relation to entrepreneurship.Journal of Small Business,26, 5–13.

Shapero, A. (1982). Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. Kent, D. Sexton, & K. Vesper (Eds.),The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship(pp. 72–90). Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall.

Sheridan, A., McKenzie, F. H., & Still, L. (2011). Complex and contradic-tory: The doing of gender on regional development boards.Gender, Work

and Organization,18, 282–297.

Shinnar, R., Pruett, M., & Toney, B. (2009). Entrepreneurship education: Attitudes across campus.Journal of Education for Business,84, 151–158. Skudiene, V., Auruskeviciene, V., & Pundziene, A. (2010). Enhancing the entrepreneurship intentions of undergraduate business students. Transfor-mations in Business & Economics,7(Suppl. A), 448–460.

Timmons, J. A., & Spinelli, S. (2007).New venture creation. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Toledano, N. (2006). Las perspectivas empresariales de los estudiantes universitarios: Un estudio empirico [Entrepreneurial perspectives of the university students: An empirical study].Revista de Educaci´on, 341, 803–825.

Veciana, J. M., Aponte, M., & Urbano, D. (2005). University students’ atti-tudes toward entrepreneurship: A two countries comparison.International

Entrepreneurship and Managament Journal,1, 165–182.

APPENDIX—RESEARCH VARIABLES AND SCALES FOR THE ANALYSIS

Construct Dimension Sub-dimension Variables Scale Dummy variable

Perceived desirability

Attitude Personal desirability High income Escape unemployment Flexible work schedule Power

Be your own boss Carry out own ideas

4-point Likert: 1= insignificant 2=few important 3=important 4=very important

0=Insignificant 1=all other options

Desirability for support from the university

Training

Course on business plans Contacts with companies Initial financial push University support office Incubator

4-point Likert: 1= insignificant 2=few important 3=important 4=very important

0=Insignificant 1=all other options

Social norms Perception of the university

Curriculum

Business plan competition Activities for the creation of

enterprises

4-point Likert: 1=very bad 2=bad 3=good 4 =very good

0=very bad and bad; 1= very good and good

Perceived feasibility

Perceived difficulties Lack of an appropriate partner

Lack of initiative Lack of courage Lack of contacts with

customers Lack of own capital Lack of external capital Lack of knowledge High financial risk Reduced earnings Support from family and/or

friends Macroeconomic

environment Fear of failure Costly regulations at the

beginning

4-point Likert: 1=strongly disagree 2=disagree 3 =agree 4=strongly agree

0=strongly disagree and disagree; 1=agree and strongly agree

Attitude toward risk Fear of risk 4-point Likert: 1=very fearful 2=fearful 3= few fearful 4=not at all fearful

0=not at all fearful; 1= all other options

Close person is an entrepreneur Close person is an entrepreneur

Dichotomous (1=yes; 2= no)

Maintained

Sex Sex Dichotomous (1=female;

2=male)

Maintained