Job-related

formal training

by employers

187

Factors associated with the

provision of job-related formal

training by employers

Paul Westhead

Department of Entrepreneurship, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK

Introduction

In many countries there has been a gradual reduction in the number of mass-production jobs with increasing job complexity and skill requirements now being characteristic of all employees. Policy-makers are aware that recruitment difficulties and skill shortages may reduce the competitiveness of small and large firms (Campbell and Baldwin, 1993). In order to move from a low skill equilibrium (Finegold and Soskice, 1988), policy-makers are aware that:

Major investments in human capital, both in the form of education and workforce training and in the form of research and development activities, appear to be an increasingly indispensable condition for enabling firms to move towards new markets and up-scale market segments that yield higher economic returns than standardised mass-commodity markets… (Buechtemann and Soloff, 1994, p. 243).

To meet chang ing requirements and market challenges, governments throug hout Europe have introduced a number of policy instruments to encourage the survival and development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Education and training support is now one of the leading measures to

increase the skill level of the workforce (Blundell et al., 1996), to ensure stronger

long-term national economic performance (Worswick, 1985; for a dissenting view see Shackleton, 1992), to reduce labour mobility (Elias, 1994), to improve employee motivation (Heyes and Stuart, 1995), to improve the internal efficiency of SMEs (A ddison and Siebert, 1994; Department of Trade and Industry, 1996), to improve business factor productivity (Bishop, 1994; Steedman and Wagner, 1989), to improve b usiness perfo rmance (Ly nch, 1994) and to achieve accreditation for BS 5750 British quality standard (Vickerstaff, 1992). In the UK, the provision of training to SMEs has become a central issue of economic policy (Miller and Davenpo rt, 1987) and is a majo r indirect small firms policy initiative. Training provision by an employer is, however, one of a range of

International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, 1998, pp. 187-216. © MCB University Press, 1355-2554

IJEBR

4,3

188

solutions to resolve skill shortages. Recruitment, changes in payment systems and/or investing in technolog y to downg rade skill requirements may also

resolve an organisation’s skill shortages problem (Pettigrew et al., 1989). T he

latter solutions are beyond the scope of this study. T his paper will contribute to the debate surrounding the factors associated with the provision of job-related formal training by employers.

T he former Conservative British Government preferred a market-based approach to the provision of training with little place fo r direct legislative backing for training (Keep and Mayhew, 1996). Nevertheless, over the last decade, the provision of training and support to SMEs increased considerably involving national and local government, the private sector and further and hig her education institutes. Responsibility fo r co-o rdinating as well as providing training moved from the Manpower Services Commission to the Training A gency. From October 1989, an even more fundamental change was the decentralisation of the Training A gency’s co-ordinating role through the creation of a regional/local network of employer-led Training and Enterprise Councils (T ECs) in England and Wales and employer-led Local Enterprise Companies (LECs) in Scotland (Employment Department, 1992). T he new training system is now controlled by locally based employer-led organisations which decide the nature and volume of training that is required[1].

Keep and Mayhew (1996) have recently argued that Britain’s skill problem is not solely due to the inadequate supply of training. T hey have asserted that a variety of facto rs ex plain the lack of employer demand fo r training. Fo r example,

… product market strategies based on a concentration on simple, standardised products and services and on low cost, low skill competition...creates a weak demand for skill. T his weak demand for skill within the economy reduces the incentives to training, which in turn produces a poorly skilled workforce (Keep and Mayhew, 1996, p. 327).

Despite research interest, it is surprising to note that:

… we know little about the determinants and effects of formal training when provided by employers and analysed from the perspective of firms (A lba-Ramirez, 1994, p. 151).

Nevertheless, a number of important management and public policy related issues related to the provision of formal training by employers were recently highlighted by Greenhalgh and Mavrotas (1996). Most notably, they suggested:

W hile employer-funded training adds to the firms stock of human capital, this stock is subject to attrition caused by inter-firm mobility of workers (often termed the “poaching problem”). In the absence of subsidies or other policies to redress the positive externality, there will be under-investment in training arising from the inability to capture returns (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1996, p. 131).

Job-related

formal training

by employers

189

If it is the latter, then the case fo r public subsidies to encourage training provision in small firms is weaker.

T his exploratory study provides a contribution to the debate, focusing on the extent, nature and determinants of job-related formal training in SMEs[2]. T he link between training provision and business performance needs to be explored but is beyond the scope of this current paper[3]. Nevertheless, drawing on a unique and new database, this study explored the combination of factors associated with the provision of various types of job-related formal training by employers located throug hout the UK. A critique of prev ious research surrounding the provision of training by employers is presented. Ignorance and market forces explanations for the uneven provision of job-related formal training are briefly summarised. Hypotheses are derived, suggesting the demog raphic characteristics of organisations, job market conditions and the perception of future recruitment difficulties are key determinants influencing the provision of training. T he data collection methodology is then described. Six types of job-related formal training are defined. Presented hypotheses are then fo rmally tested. Conclusions and implications fo r policy -makers and practitioners are detailed in the final section.

Critiquing prior work in this area

T he limited number of studies which have focused on the provision of job-related formal training by employers has isolated a number of key issues influencing the provision of training. Not surprisingly, many questions still remain unanswered (A ltonji and Spletzer, 1991). In addition, previous research is inevitably open to criticism. First, the majority of studies have focused on

individual employees (Blundell et al., 1996; Booth, 1991) and have provided little

information on the employer, who is at the heart of the training provision discussion (Osterman, 1995). Second, the limited number of employer-based studies have generally focused on the provision of training within a single

locality (Elias and Healey, 1994; Fuller et al., 1991; Goss and Jones, 1992;

Johnson and Gubbins, 1992; Jones and Goss, 1991; Kirby, 1990)[4]. It has, however, been acknowledged (Veum, 1996) that it is difficult to generalise from a single locality. T hird, it is also difficult to generalise from small samples of employers (Johnson and Gubbins, 1992; Jones and Goss, 1991; Kirby, 1990; Osterman, 1995). Fourth, comparative research in this area is very difficult because a variety of definitions of training have been utilised. Some studies have adopted a very broad definition of training to include informal as well as formal training (A bbott, 1993), while others have used a narrower definition which focused on formal training alone (Elias and Healey, 1994). Fifth, not all studies have disting uished between different ty pes of training (notable

exceptions to this trend are the studies conducted by A bbott (1993), Baldwinet

al., (1995), and Curran et al., (1993, 1996), Elias and Healey (1994)). Sixth, few

IJEBR

4,3

190

failed to clarify some of the causal mechanisms at wo rk influencing the provision of training (A lba-Ramirez, 1994; Elias and Healey, 1994).

T his study seeks to overcome the above problems. T he first is addressed by collecting information directly from employers. T he second is overcome by exploring the provision of training by employers located throughout the UK. T he third is addressed by drawing on survey evidence from a sample of 312 organisations. T he fourth is overcome by utilising the definitions of job-related formal training presented by Elias and Healey (1994). T he fifth problem is addressed by detailing the provision of six types of job-related formal training. T he six th problem is overcome by ex plo ring the combination of facto rs associated with the provision of various types of job-related training within a multivariate framework.

Theoretical frameworks

A framework approach (Porter, 1991; Westhead, 1995) was utilised to guide and structure this study. By highlighting the diversity of competitive situations and the factors which are significantly associated with the provision of job-related fo rmal training, this approach enabled prev ious research finding s to be supported as well as challenged. In this context, ignorance and market forces explanations (Storey and Westhead, 1997) are briefly summarised below.

Ignorance explanation

Owners/managers have a pivotal role in the decision-making processes leading to the provision of job-related formal training (Matlay, 1996). Research has revealed that the owners/managers of knowledge-based and professional

services firms generally have above average levels of education (Curran et al.,

1991) and this, in part, may explain why firms engaged in these activities are

more likely to have provided training for some of their employees (Curran et al.,

1996). A sizeable proportion of owners/managers of small firms, particularly those with minimal formal educational qualifications (Greenhalgh and Stewart, 1987), may, however, be ignorant/unaware of the variety of training schemes on

offer (Birley and Westhead, 1992; Fuller et al., 1991). On the basis of this

ignorance explanation, policy-makers have formulated policy and introduced a series of schemes to make owners/managers of small firms aware of the benefits associated with a trained workforce.

Market forces explanation

Market forces can explain the lower provision of job-related formal training in small firms. For example, the heterogeneity of the small firms sector can add to the unit cost of supply ing a training course to employees in small firms. Providers of training to small firms also have to contact a large number of indiv iduals and enter into separate and indiv idual negotiations and ag reements. In each case, the number of trainees is generally very small (Vickerstaff, 1992). Because small firms usually desire customised training

Job-related

formal training

by employers

191

Fuller et al., 1991; Kirby, 1990; Matlay, 1996), the fixed cost of providing a

training course to a small number of employees in a small firm is, therefore, usually much higher than the fixed cost of providing a standard training package to a large number of employees employed in a large firm (Lynch, 1994). Demand factors also influence the lower provision of job-related formal training in small firms. Owners/managers of small firms have short-term time horizons and usually focus on the short-term performance of their ventures.

T he pressure of work in a small firm environment (Fuller et al., 1991) as well as

the direct cost of training (V ickerstaff, 1992) can, therefo re, prevent an owner/manager releasing his/her employees to attend a formal training course. Moreover, owners/managers of small firms may be reluctant to release their employees if there is an opportunity cost to the business associated with their

employees attending a formal training course (Curran et al.,1996; Kirby, 1990;

Matlay, 1996). T hese opportunity costs are likely to be higher in smaller rather than larger firms. A t the most simplistic level, in a two-person firm, the absence of one person on a training course can clearly have a direct impact on firm performance, whereas one person’s absence may have a minute impact on a thousand employee firm (Lynch, 1994; Storey and Westhead, 1997). In addition, employers may only release their employees to attend off-the-job formal training courses if the training satisfied industry-wide standards and/or agreed qualifications (for example, those associated with accountancy and transport) (Johnson and Gubbins, 1992).

Drawing on a study of fast-growth firms in the UK, Wynarczyk et al. (1993)

noted the absence of an internal labour market (ILM) in a small firm can impede the provision of formal training. Most notably, they found small firm owners expected their manager’s next job would be outside his/her small firm. Not surprisingly, many small firm owners have comparatively little incentive to provide their managers with additional job-related formal training.

T he provision of job-related formal training by an employer as well as the take-up of this training by a recipient employee is an important investment decision[5]. Both parties generally weigh the current costs of training against the potential benefits associated with its provision and take-up (Greenhalgh and Stewart, 1987)[6,7]. Employers providing training appreciate that the period of expected return is more uncertain for the employer than the recipient employee. Not surprisingly,

Discouraged by such an uncertainty, some firms refrain from making any training commitment and rely on the educational system at large or on other firms in obtaining trained workers (A lba-Ramirez, 1994, p. 151).

Owners/managers of small firms appreciate that the providers of the job-related

formal training may not benefit from the training investment (Baldwin et al.,

1995; Fuller et al., 1991)[8]. With this in mind, investments in non-portable

IJEBR

4,3

192

mo re money (Keep and May hew, 1996). T here is also a risk that trained employees will be “poached away” (Jones and Goss, 1991) by other employers which are prepared to pay a remuneration premium to trained employees[9]. Without a subsidy to redress this job mobility externality, many small firms may under-invest in training provision because they are unable to capture the returns associated with their training investment (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1996).

Based on their recent study of service sector employers, Curranet al.(1993),

however, warned that the often referred to reluctance of small firms to train may as much reflect employees’ attitudes as well employers’. A s intimated above, the conventional view of training in the small firm sector is that the employer is reluctant to invest, on the g rounds that the worker is likely to be “poached

aw ay ” by competito rs. Curran et al., (1993) w hile not discounting the

“poaching” problem, found small firm employees were reluctant to participate in training, on the grounds that they did not require more training to do their jobs better.

Derivation of hypotheses

During their detailed review, Hendry et al. (1991a) noted that the organisational

character of a business (for example, its age, size, ownership form and main industrial activity) could have an impact on its openness to new practices and ultimately the provision of training. Further, the infrastructure for training (for example, the activities of local enterprise and development agencies, T ECs, LECs, etc.), especially in the locality where the business was based, could encourage some resource-constrained small firms to provide formal training for some of their employees for the first time.

A variety of triggers can lead to the provision of training by employers.

Hendry et al. (1991a) noted, in most SMEs, the desire for new learning was

generally promoted by facto rs associated with sho rt-term economic and bottom-line pressures. For example, to rectify problems of production and to improve production/service efficiency. In addition, they noted the need for training by an SME reflected the quality of the labour supply in the local market where the firm was located as well as the characteristics of the competition faced by an SME to recruit suitable employees.

Building on previous empirical research, the remainder of this section formulates hypotheses to explain the uneven provision of job-related formal training. T hese hypotheses are then tested within a multivariate statistical framework.

Demographic characteristics of organisations

Job-related

formal training

by employers

193

schemes (Soskice, 1994) for young employees who were prepared to forego some personal financial remuneration during their apprenticeship in order to gain a credentialised ticket for skilled employment in a large firm environment (see Table I).

Large organisations have provided training to improve communication, reduce monitoring costs and allow an effective management of employees

(Barron et al., 1987). Training has also been provided by large organisations to

ensure a high standard of product/service delivery to their customers (Begg,

1990). Further, during their detailed review, Baldwin et al. (1995, p. 18) noted,

… large firms have access to cheaper capital to finance investment in training (Hashimoto, 1979), that large firms can reduce the risk and therefore the cost of investment in training by pooling risks (Gunderson, 1974) and that large firms have a g reater pay-off from training because their size and their exploitation of economies of scale have led to task specialization and, thus, a greater benefit for training (Doeringer and Piore, 1971).

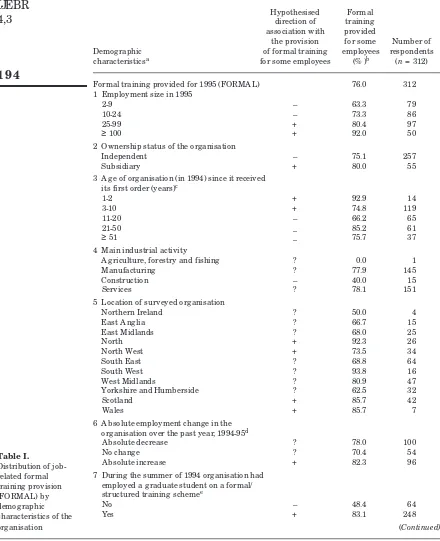

Consequently, it was hypothesised that a large employment-sized organisation (row 1 in Table I) would be significantly more likely to have provided job-related formal training.

A subsidiary organisation which forms part of a g roup may have a more extensive division of labour than an independent org anisation (Elias and Healey, 1994). To develop a common group culture, as well as to ensure control and work practice systems are in place throughout the group, a parent company with considerable resources, information and technical assistance (Osterman, 1995) may encourage training in their subsidiary o rg anisations. It w as, therefore, hypothesised that a subsidiary organisation would be more likely to

have provided training than an independent organisation (O’Farrellet al., 1993;

Osterman, 1995) (row 2).

Similarly, in order to integ rate employees into the ways of the business, recently established organisations which may utilise newer technologies and

have higher skill requirements (Baldwinet al., 1995) were hypothesised to have

provided formal training (row 3) (Elias and Healey, 1994). It has, however, been

suggested (Baldwin et al., 1995) that older organisations which have more

established and dense networks might be expected to have better information about w here training would be most useful compared w ith younger organisations.

Owing to differences in the technologies used and the kinds of products and services provided, employers engaged in some industrial activities may have

different training needs (Deloitte, Haskins and Sells et al., 1989). For example,

the use of advanced manufacturing technologies has been found to be positively

related to the provision of training (Baldwin et al., 1995). A bbott (1993) has,

IJEBR

the provision for some Number of Demographic of formal training employees respondents characteristicsa for some employees (% )b (n= 312) Formal training provided for 1995 (FORMA L) 76.0 312 1 Employment size in 1995

2-9 – 63.3 79

10-24 – 73.3 86

25-99 + 80.4 97

≥100 + 92.0 50

2 Ownership status of the organisation

Independent – 75.1 257

Subsidiary + 80.0 55

3 A ge of organisation (in 1994) since it received its first order (years)c

A griculture, forestry and fishing ? 0.0 1

Manufacturing ? 77.9 145

Yorkshire and Humberside ? 62.5 32

Scotland + 85.7 42

Wales + 85.7 7

6 A bsolute employment change in the organisation over the past year, 1994-95d

A bsolute decrease ? 78.0 100

No change ? 70.4 54

A bsolute increase + 82.3 96

Job-related

formal training

by employers

195

small number of broad industrial categories. Nevertheless, some studies have noted that organisations engaged in the construction sector were significantly less likely to have provided training for some of their employees (row 4) (Miller and Davenpo rt, 1987; Green, 1993). T he lower prov ision of training by construction businesses may, in part, be due to the fact that employers in this sector generally use labour-only subcontractors (who are already trained) rather than direct employees and often use them for short time periods (Curran

et al., 1996).

Labour market conditions may influence the provision of job-related formal

training (Baldwin et al., 1995). To encourage local business development a

variety of agencies (for example, local enterprise and development agencies, T ECs and LECs, the Welsh Development A gency and the Development Board for Rural Wales in Wales, Scottish Enterprise and the Highlands and Islands Development Board in Scotland and the Rural Development Commission in England and the Local Enterprise Development Unit (LEDU) in Northern Ireland) have directly (and indirectly) encouraged employers to provide job-related training. By contacting small firms and showing them how training provision can benefit their businesses (for example, training can remove a competitive constraint such as a skills gap created by technological change) local development agencies may have removed the ig no rance barrier. Consequently, it w as hy pothesised that the activ ities of local agencies, particularly those covering government-designated assisted areas for regional

Hypothesised Formal direction of training association with provided for

the provision some Number of Demographic of formal training employees respondents characteristicsa for some employees (% )b (n= 312) 8 Over the next two years recruitment will

present no difficulty

Disagree + 79.9 199

A gree – 69.0 113

Notes:

a Data gathered from postal questionnaires

b A n organisation was classified as a formal training provider if a respondent indicated employees received one or more of the following training programmes in 1995: planned on-the-job training by superiors; full-time courses lasting up to one week; full-time courses lasting over one week; day release courses; or other part-time courses

c A ge of business data available for 296 out of the 312 organisations

d A bsolute employment change data available for 250 out of the 312 organisations

e A t a finer level of analysis, 84 per cent of ST EP businesses had provided some type of job-related formal training compared with 48 per cent of non-ST EP businesses

(+ ) Positively associated with the provision of job-related formal training (–) Negatively associated with the provision of job-related formal training

IJEBR

4,3

196

assistance (Birley and Westhead, 1992), may have encouraged the provision of job-related training by employers located in the North and North West of England, Scotland and Wales (row 5).

Job market conditions

T he amount of training provided by an organisation is, in part, determined by the nature of the job market it faces (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1994). A growing business may train new recruits as they join the business (Johnson and Gubbins, 1992). Similarly, if a business is located in a labour market associated with skill shortages it may internally train existing members of staff (Elias and

Healey, 1994; Fulleret al., 1991)[11]. In addition, organisations which have

experienced rapid employment growth and/or recruitment difficulties may have participated on externally organised formal/structured training programmes to enable their employees to take on new functions associated with dealing with

larger, and perhaps more diversified, markets (Baldwin et al., 1995). It was,

therefore, hypothesised that organisations which have increased their absolute employment sizes over the past year will be more likely to have provided some type of training (row 6).

Employers generally participate on formal/structured g raduate placement schemes to gain new ideas and fresh insights into new business practices

(Holmes et al., 1994). By prov iding placements to g raduate students,

participating businesses may also increase their sales revenues after the placement period (Westhead, 1997). A fter a rewarding training experience, employers may have provided job-related formal training for new recruits as well as ex isting employees. Consequently, it w as hy pothesised that org anisations which employed a g raduate student on a formal/structured training scheme in 1994 were more likely to have subsequently provided formal training for some of their employees (row 7).

Future recruitment expectations

Similar arguments to those discussed above have been used to suggest that organisations which expect future recruitment difficulties are more likely to

train their existing employees (Elias and Healey, 1994; Fulleret al., 1991)[12]. It

was, therefore, hypothesised that organisations which perceived “over the next two years recruitment will present no difficulty ” were less likely to have provided formal training for some of their employees (row 8).

Data collected

Job-related

formal training

by employers

197

the identification of new skills (Kirby and Mullen, 1990). Further, the prog ramme encourages participating students to ex plo re future career opportunities in the small business sector (see Table II).

T his study explored the provision of job-related formal training within a new data set which contained a broad spectrum of employers located throughout the UK. Row 1 in Table II show s, during 1994, 909 “ host” ST EP b usinesses provided student projects (column 1). To ascertain the characteristics and aspirations of businesses participating on the Shell Technolog y Enterprise Programme a structured questionnaire was designed by the Centre for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises at the University of Warwick and Shell UK Limited. T his questionnaire w as posted by Shell UK Limited to all 909 participating ST EP businesses. In total, a sample of 527 ST EP businesses completed a structured questionnaire prior to the placement (column 2) (58 per cent response rate)[13]. From this sample, 353 ST EP “ host” businesses completed a structured questionnaire at the end of their placement (column 3). Twelve months after the 1994 ST EP placement, 244 out of this latter g roup of 353 businesses responded to a further structured questionnaire (69 per cent response rate) (column 4).

T he first ST EP b usiness questionnaire w as desig ned to collect basic

information on the organisation (Holmeset al., 1994). T he second questionnaire

was designed to see whether expectations surrounding the prog ramme had been realised. T he third questionnaire, 12 months after the placement, ascertained whether organisations, in 1995, had provided job-related formal training for some of their employees. Information was, in addition, gathered surrounding the employment performance of organisations over the past year as well as respondents’ perceptions surrounding future recruitment difficulties (Westhead, 1997).

It is acknowledged that participating ST EP businesses were self-selecting (A shenfelter and Card, 1985; Veum, 1995). For example, businesses pursuing growth strategies may be more likely to put themselves forward for the Shell

Number

of ST EP Pre-ST EP Eight weeks 12 months placements (1994) after ST EP after ST EP Type of business in 1994 interviews (1994) (1995)a,b

1 ST EP 909 527 353 244

2 Non-ST EP nil 160 nil 84

Total – 687 353 328

Notes: a ST EP businesses responding to the questionnaire eight weeks after the Shell Technology Enterprise Programme were sent a further questionnaire 12 months after ST EP

b Non-ST EP businesses responding to the questionnaire sent to them in 1994 were sent a further questionnaire 12 months later

Table II.

IJEBR

4,3

198

Technolog y Enterprise Prog ramme than, say, conservative firms pursuing survival strategies. In addition, students with high initial ability, motivation, career aspirations, attitudes and aptitude (Fredland and Little, 1980; Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1994) may be more likely to put themselves forward for the Shell Technology Enterprise Programme. Non-random participation on the programme can, therefore, come from two sources: businesses and students. To address the problem of non-random participation by businesses, the methodological approach utilised during the evaluation of the 1994 Shell

Technology Enterprise Programme was to identify a control group (Marshallet

al., 1993, 1995; Rosenthal, 1996) of businesses which had not participated in the

1994 prog ramme. T his matched sample methodology enabled the potential

additionality (Flemming, 1994; Marshall et al., 1995) prov ided by the

prog ramme to be identified. Further, the potentially disto rting effect on recorded outcomes by sample selection bias (Heckman, 1979) (i.e. only looking at the outcomes/performance of “host” businesses on the 1994 programme) was addressed by the matched sample methodology.

Dun and Bradstreet provided the database for the sample of businesses which potentially had not participated in the 1994 Shell Technology Enterprise Prog ramme. A structured questionnaire fo r non-ST EP b usinesses w as desig ned by the Centre fo r Small and Medium Sized Enterprises at the University of Warwick and Shell UK Limited. T his questionnaire was posted by Shell UK Limited to the names and addresses of businesses supplied by Dun and Bradstreet. Row 2 (column 2) in Table II shows a sample of 160 businesses which had not participated in the programme (or any earlier Shell Technology Enterprise Programme) were also interviewed in 1994.

T his control group of non-ST EP businesses was selected on the grounds that they did not differ significantly from the 527 responding ST EP businesses. Choice of matching criteria was influenced by previous studies which have noted a significant relationship between business demographic characteristics and business performance (Birley and Westhead, 1990; Storey, 1994; Westhead and Birley, 1995). Five criteria were selected to match the two g roups of businesses: employment size, age, ownership status, main industrial activity and the location of the business. T he matching of the 527 ST EP and 160 non-ST EP businesses was successful with regard to employment size (means of 52.5 and 43.9 employees fo r responding ST EP and non-ST EP b usinesses respectively), age (means of 23.6 and 22.8 years for responding ST EP and non-ST EP businesses, respectively), ownership status (79 per cent of non-ST EP as well as non-ST EP businesses were independent businesses) and main industrial activity with regard to four broad industrial categories (for example, 48 per cent and 50 per cent of ST EP and non-ST EP businesses were principally engaged in

manufacturing activities) (Holmeset al., 1994). However, the matching was not

Job-related

formal training

by employers

199

samples were different in another major respect. ST EP businesses were significantly more likely to have employed in 1994 staff holding degrees than the non-ST EP businesses (74 per cent compared with 64 per cent).

Twelve months later, 84 out of the o rig inal 160 non-ST EP b usinesses responded to a further questionnaire (53 per cent response rate) (column 4). T his second questionnaire ascertained whether the businesses, in 1995, had provided job-related formal training for some of their employees.

Despite the problem of sample attrition, ST EP and non-ST EP business respondents to the follow-on questionnaire in 1995 were overall representative of the businesses surveyed in 1994 and were still matched with one another[14]. To compare this study’ findings with those presented by Elias and Healey (1994), this study explored the provision of job-related formal training in a combined sample of ST EP and non-ST EP businesses which had more than one employee at the time of the survey in 1995. T he combined database of ST EP and non-ST EP businesses included firms in a variety of industries, locations, ownership forms, ages and employment sizes.

Defining job-related formal training

Defining “training” is a conceptually difficult task (Campanelliet al., 1994). A s

intimated above, a variety of definitions have been presented and utilised, which makes comparative research in this area difficult. Further, training is a difficult concept to quantify because employees can receive training through a variety of methods (Lynch, 1991, 1992; OECD, 1991).

In the UK, public subsidies have been targeted towards job-related formal training schemes. Not surprisingly, policy-makers are interested in the factors which either encourage or impede the provision of job-related formal training. To contribute to this important debate, this exploratory study focused on the provision of job-related formal training provided by employers. T he factors associated with the provision of informal in-house training (which is regarded as the most frequently provided type of training by small firms) were not explored in this study. A detailed discussion surrounding the informal training

issue has been presented elsewhere (A bbott, 1993; Curran et al., 1996; Goss and

Jones, 1992; Hendry et al., 1991b; Johnson and Gubbins, 1992; Vickerstaff,

1992)[15].

Various types of job-related formal training were identified by Elias and Healey (1994) during their study of employers. Following Elias and Healey (1994, p. 581), owner-managers and/or senior managers of ST EP and non-ST EP businesses were asked to indicate on a self-completion postal questionnaire whether employees in their organisation had received any of the following types of training:

• guidance from colleagues when needed (only);

• planned on-the-job training by superiors;

IJEBR

4,3

200

• full-time courses lasting over one week;

• day release courses;

• other part-time courses;

• other (please specify);

• no response.

T he “no response” category suggested respondents did not provide any kind of formal training. Similarly, the “guidance from colleagues when needed (only)” category was not intended to represent a formal training category. Elias and Healey (1994, p. 581) asserted,

It exists to differentiate those employers who have no formal training programmes from those who do, at the same time allowing the respondent to make a positive response to the question.

T he following section explores the combination of factors associated with the provision of six types of job-related formal training. T he first training type – FORMA L – provided a crude indication of the extent and depth of job-related fo rmal training prov ided by employers. T his definition disting uished employers which had provided some type of formal training (for example, either planned on-the-job training by superiors, full-time courses lasting up to one week, full-time courses lasting over one week, day release courses and/or part-time courses) from those which had not provided any formal training (for example, a “no response” to the question or “guidance from colleagues when needed (only))”. A further five formal job-related training types covering the provision of planned on-the-job training by superiors (PLA NNED), full-time courses lasting up to one week (FT ONE), full-time courses lasting over one week (FT OVER), day release courses (DAY ) and other part-time courses (OT HERPT ) are defined in the Appendix.

Results

T he extent and nature of job-related formal training provision

Table III shows 76 per cent of respondents from this national survey had prov ided their employees w ith some kind of job-related fo rmal training (FORMA L). A total of 24 per cent of employers either gave “no response” to the question or indicated only “guidance from colleagues when needed”. T his reported level of formal training provision was virtually the same as that noted by Elias and Healey (1994) (75.3 per cent)[16]. Moreover, as found by Elias and Healey, “planned on-the-job training” by superiors (PLA NNED) was the most frequently cited type of fo rmal training provided by employers. A larger proportion of employers in the current study had, however, utilised “other part-time courses” (OT HERPT ).

Job-related

formal training

by employers

201

formal training for some of their employees (row 1). In marked contrast, only 63 per cent of the org anisations w ith between two and nine employees had provided job-related formal training for some of their employees.

Multivariate analysis

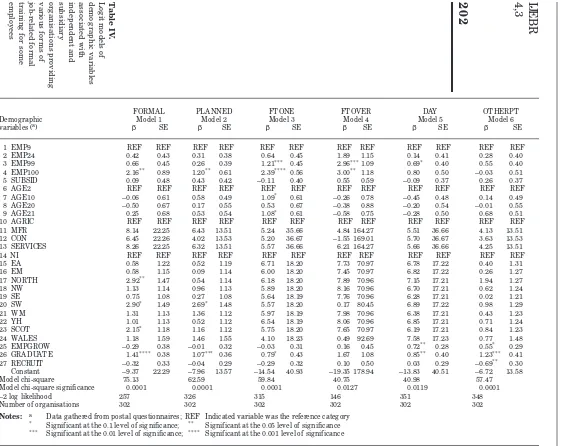

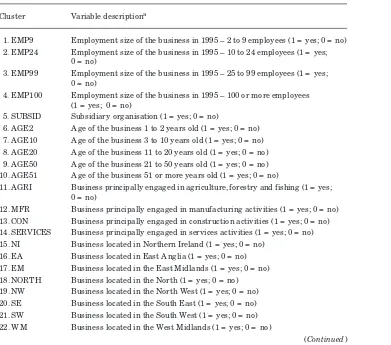

For each of the six job-related formal training definitions, a multivariate linear logistic reg ression model is detailed in Table IV. T his multivariate technique has frequently been utilised in training provision studies (Elias and Healey, 1994). T he parameters were estimated by a maximum likelihood method using the SPSS/PC+ V 4.0 prog ram (No rusis, 1990). Each model ex plo red the relationship between the dependent variable and selected ex planato ry variables[17]. A full description of all the explanatory variables is presented in the Appendix.

Model 1 included complete questionnaire returns from 238 organisations[18]. T he model was statistically significant at the 0.0001 level of significance. A s hypothesised, organisations with between 25 and 99 employees (EMP99) and those with 100 or more employees (EMP100) were significantly more likely to have provided some type of job-related training (FORMA L).

Young org anisations between one and two years old (AGE2) and those between three and ten years old (AGE10), as posited, had provided some type of job-related formal training. Established organisations between 21 and 50 years old (AGE50) were also significantly more likely to have provided some type of formal training. We can speculate, based on this evidence, that some established organisations responding to changing market and technological conditions (for

Total Total Elias and current study Healey (1994) study

(n= 312)a,b (n= 2,028)b,c Type of training provided to some employees No. % %

No response 73 23.4 9.3

Guidance from colleagues when needed (only) 2 0.6 15.4 Formal training (FORMA L) 237 76.0 75.3 Planned on-the-job training by superiors (PLA NNED) 203 65.1 58.9 Full-time courses lasting up to one week (FT ONE) 100 32.1 21.8 Full-time courses lasting over one week (FT OVER) 30 9.6 10.8 Day release courses (DAY) 112 35.9 35.6 Other part-time courses (OT HERPT ) 125 40.1 22.6

Other (please specify) 0 0.0 5.8

Notes: a Data provided by 235 organisations which had participated in the 1994 Shell Technology Enterprise Programme and a further 77 matched non-ST EP organisations which had not participated in the Shell Technology Enterprise Programme

bBusinesses which had more than one employee at the time of the survey in 1995 c Elias and Healey (1994), Table 3, p. 582

Table III.

Type of training employees provided in surveyed organisations in the current study and the Elias and Healey

IJ

FORMA L PLA NNED FT ONE FT OVER DAY OT HERPT

Demographic Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

variables (a) β SE β SE β SE β SE β SE β SE

1 EMP9 REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF

2 EMP24 0.42 0.43 0.31 0.38 0.64 0.45 1.89 1.15 0.14 0.41 0.28 0.40

3 EMP99 0.66 0.45 0.26 0.39 1.21*** 0.45 2.96***1.09 0.69* 0.40 0.55 0.40

4 EMP100 2.16** 0.89 1.20** 0.61 2.39**** 0.56 3.00** 1.18 0.80 0.50 –0.03 0.51

5 SUBSID 0.09 0.48 0.43 0.42 –0.11 0.40 0.55 0.59 –0.09 0.37 0.26 0.37

6 AGE2 REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF

7 AGE10 –0.06 0.61 0.58 0.49 1.09* 0.61 –0.26 0.78 –0.45 0.48 0.14 0.49

8 AGE20 –0.50 0.67 0.17 0.55 0.53 0.67 –0.38 0.88 –0.20 0.54 –0.01 0.55

9 AGE21 0.25 0.68 0.53 0.54 1.08* 0.61 –0.58 0.75 –0.28 0.50 0.68 0.51

10 AGRIC REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF

11 MFR 8.14 22.25 6.43 13.51 5.24 35.66 4.84 164.27 5.51 36.66 4.13 13.51

12 CON 6.45 22.26 4.02 13.53 5.20 36.67 –1.55 169.01 5.70 36.67 3.63 13.53

13 SERVICES 8.26 22.25 6.32 13.51 5.57 36.66 6.21 164.27 5.66 36.66 4.25 13.51

14 NI REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF REF

15 EA 0.58 1.22 0.52 1.19 6.71 18.20 7.73 70.97 6.78 17.22 0.40 1.31

16 EM 0.58 1.15 0.09 1.14 6.00 18.20 7.45 70.97 6.82 17.22 0.26 1.27

17 NORT H 2.92** 1.47 0.54 1.14 6.18 18.20 7.89 70.96 7.15 17.21 1.94 1.27

18 NW 1.13 1.14 0.96 1.13 5.89 18.20 8.16 70.96 6.70 17.21 0.62 1.24

19 SE 0.75 1.08 0.27 1.08 5.64 18.19 7.76 70.96 6.28 17.21 0.02 1.21

20 SW 2.90* 1.49 2.69* 1.48 5.57 18.20 0.17 80.45 6.89 17.22 0.98 1.29

21 WM 1.31 1.13 1.36 1.12 5.97 18.19 7.98 70.96 6.38 17.21 0.43 1.23

22 YH 1.01 1.13 0.52 1.12 6.54 18.19 8.06 70.96 6.85 17.21 0.71 1.24

23 SCOT 2.15* 1.18 1.16 1.12 5.75 18.20 7.65 70.97 6.19 17.21 0.84 1.23

24 WA LES 1.18 1.59 1.46 1.55 4.10 18.23 0.49 92.69 7.58 17.23 0.77 1.48

25 EMPGROW –0.29 0.38 –0.01 0.32 –0.03 0.31 0.16 0.45 0.72** 0.28 0.55* 0.29

26 GRA DUAT E 1.41**** 0.38 1.07*** 0.36 0.79* 0.43 1.67 1.08 0.85** 0.40 1.23*** 0.41

27 RECRUIT –0.32 0.33 –0.04 0.29 –0.29 0.32 0.10 0.50 0.03 0.29 –0.69** 0.30

Constant –9.37 22.29 –7.96 13.57 –14.54 40.93 –19.35 178.94 –13.83 40.51 –6.72 13.58

Model chi-square 75.13 62.59 59.84 40.75 40.98 57.47

Model chi-square significance 0.0001 0.0001 0.0001 0.0127 0.0119 0.0001

–2 log likelihood 257 326 315 146 351 348

Number of organisations 302 302 302 302 302 302

Notes: a Data gathered from postal questionnaires; REF Indicated variable was the reference category

* Significant at the 0.1 level of significance; ** Significant at the 0.05 level of significance

*** Significant at the 0.01 level of significance; **** Significant at the 0.001 level of significance

Job-related

formal training

by employers

203

example, after an ownership and/or a management transition) had provided training to enhance their competitive performance.

T he nature of the main product/serv ice prov ided by an employer was sig nificantly associated w ith the dependent variable. A s hy pothesised, organisations engaged in the construction sector (CON) were significantly less likely to have provided some type of job-related formal training.

A s posited, businesses located in the North of England (NORT H) were significantly more likely to have provided job-related training for some of their employees[19]. T he activities of local development agencies such as T ECs and the Rural Development Commission in the North of England may, in part, have directly as well as indirectly encouraged the provision of training by employers. Organisations located in South West England (SW ) were also significantly associated with the dependent variable[20]. Regional policy support as well as a signposting role played by T ECs and the Rural Development Commission may, therefore, have encouraged the provision of formal training by employers. A s hypothesised, organisations that had employed a graduate student on a formal/structured training scheme during the summer of 1994 (GRA DUAT E) were more likely to have provided some form of job-related formal training for some of their employees in 1995. T his graduate training experience may have encouraged some organisations to provide job-related formal training for their new recruits and/or established members of staff.

Model 2 was significant at the 0.0020 level and included five significant explanatory variables. A s found in Model 1, organisations which had employed a g raduate student on a formal/structured training scheme (GRA DUAT E), those with 100 or more employees (EMP100), those organisations between 21 and 50 years old (AGE50) and those located in South West England (SW) were more likely to have provided some planned on-the-job training (PLA NNED). A lso, as found in Model 1, organisations engaged in the construction sector (CON) were sig nificantly less likely to have prov ided planned on-the-job training for some of their employees.

T he provision of full-time courses lasting up to one week (FT ONE) was mainly determined by organisation size. Model 3 was significant at the 0.0003 level. Organisations with between 25 and 99 employees (EMP99) and those with 100 or more employees (EMP100) were significantly more likely to have allowed their employees to attend full-time courses lasting up to one week.

IJEBR

4,3

204

Model 5 was significant at the 0.0035 level and included four significant explanato ry variables. A s found in Models 1, 3 and 4 o rg anisations with between 25 and 99 employees (EMP99) and those with 100 or more employees (EMP100) were significantly more likely to have allowed their employees to attend off-the-job day release courses (DAY). T his type of training provision was also markedly more likely in young organisations between one and two years old (AGE2) and g row ing o rg anisations w hich had reco rded an absolute employment increase over the past year (EMPGROW).

T he explanatory variables associated with the provision of off-the-job other part-time courses (OT HERPT ) are summarised in Model 6. T his model was significant at the 0.0036 level and included three significant explanatory variables. T he provision of other part-time courses was significantly more likely in o rg anisations w hich had employed a g raduate student on a formal/structured training scheme (GRA DUAT E) and in those organisations which perceived over the next two years recruitment would present a difficulty (RECRUIT ). A lso, as found in Model 5, other part-time courses provision was more likely in growing organisations (EMPGROW).

Conclusions and implications

Over the last decade, there has been a considerable g rowth in the training industry in relation not only in the number but also the variety of training schemes on offer (Planning Exchange, 1995), much of it supported from the public purse. Responding to this increased supply of training schemes, 76 per cent of respondents from this national survey of employers suggested their employees had been provided with some type of job-related formal training (FORMA L). T his evidence confirms the earlier finding by Elias and Healey (1994) drawing on a survey of employers in a single locality.

T his study has made a contribution to the literature measuring the extent and combination of factors associated with the provision of various types of job-related formal training. It is an advance on previous research because this study explored extensive contextual data from individual SMEs located in many more localities than earlier studies. Most notably, this study has provided quantitative statistical evidence surrounding the combination of business demog raphic characteristics, job market conditions and future recruitment ex pectations facto rs associated with the prov ision of planned on-the-job training as well as various types of off-the-job formal training. Presented results have also supported certain views included in the ignorance and market forces theoretical frameworks.

Job-related

formal training

by employers

205

can infer that the provision of job-related formal training by employers reflected the operation of the market place in an entirely predictable manner. A variety of supply (for example, it is more expensive to supply customised training to small rather than large firms) and demand (for example, small firms do not have internal labour markets, small firms generally focus on short-term performance issues, owners/managers fear that the training on offer is irrelevant and not customised to their needs and their trained employees would be cherry-picked and poached away by larger employers) market forces factors explain the lower likelihood that a very small firm will provide formal training (Storey and Westhead, 1997). A case for public subsidies to encourage the provision of training in small firms which are already aware of the benefits of training, cannot, therefore, be justified.

A striking finding from this ex plo rato ry study w as the sig nificant relationship between w hether an o rg anisation had participated on an inex pensive and focused formal/structured g raduate student placement scheme (GRA DUAT E) and the prov ision of planned on-the-job training (PLA NNED) and off-the-job other part-time courses (OT HERPT ). We can speculate, based on the presented evidence, that the ignorance barrier to training provision can be removed if SMEs directly experience the benefits associated with training provision.

T his study identified a significant relationship between the location of an organisation and the provision of planned on-the-job training (PLA NNED) as well as the broad and all-inclusive FORMA L dependent variable. With regard to the latter dependent variable (Model 1), the prov ision of training by employers was found to be markedly more likely in the North and South West of England. In these environments, a variety of locally- and sectorally-based development agencies have provided subsidised job-related formal training to employers. Many locally-based development agencies, however, do not have the resources and skills to be direct training providers. Nevertheless, locally-based development agencies may have personally communicated to employers the benefits of a hig hly skilled and trained wo rkfo rce. Many locally -based development agencies are business advisory centres (Haughton, 1993) which signpost to owners/managers sources of professionally qualified business advice (Dunsby, 1996) and training assistance from a variety of public agencies

and private sector training providers (for a dissenting view see Curran et al.,

1996). Based on the aggregate statistical evidence presented in Table IV, we can speculate that public subsidies directed towards local development agencies may have directly as well as indirectly encouraged the provision of training (particularly, planned on-the-job training) by employers.

IJEBR

4,3

206

of their employees to attend day release courses (DAY) (Model 5). Further, more established organisations between 21 and 50 years old (AGE50) (for example, responding to an ownership and/or a management transition) had allowed some of their employees to attend planned on-the-job training courses (Model 2).

T he explanatory variables found to be associated with provision of planned on-the-job training were not exactly the same as those associated with the provision of various types of off-the-job training (for a similar conclusion see

Baldwinet al. (1995)). For example, growing organisations (EMPGROW) were

significantly more likely to have provided off-the-job training (Models 5 and 6). Growing organisations aware of the opportunity costs associated with training provision had, therefore, sought to rectify their immediate skills sho rtage problems by allowing some of their employees to attend day release courses and/or other part-time courses. Organisations which perceived skill shortages in the next two years (RECRUIT ) were also markedly more likely to have allowed some of their employees to attend other part-time courses.

We can infer from the presented evidence that broad-brush policy initiatives to a diverse g roup of all small firms may not be the most effective way to encourage mo re small firms to prov ide job-related training schemes. Development agencies and locally and sectorally-based training providers must appreciate that very small businesses require customised on-the-job and/or off-the-job training. Training providers must not only appreciate the characteristics of the employees potentially in receipt of training, but also the status of the business along its growth trajectory (Storey and Westhead, 1997).

Not surprisingly, locally- and sectorally-based agencies which have not been allocated sufficient resources to contact and assist all employers generally do not favour a broad-brush policy approach to encourage job-related training in all organisations. In response to resource scarcity, agencies may prefer to target economic resources, such as training support, to the relatively small proportion of firms which not only have the desire to grow but also the ability with some assistance to be significant employers (Storey, 1993). To maximise the benefits associated with their resource allocation decisions, agencies may decide, for example, to target training resources to larger employers and those that have already shown a willingness to participate on a formal/structured g raduate student work experience prog ramme. T his targeted policy stance inevitably has its critics. Nevertheless, a proactive and targeted policy stance towards the provision of training to potential high-flyers may be the only practicable option open to agencies with limited budgets which need to provide quick solutions to deep structural problems in their communities.

Training providers (such as local development agencies, T ECs, LECs, etc.) which decide to encourage the provision of job-related training in SMEs must:

Job-related

formal training

by employers

207

To encourage more SMEs to provide job-related formal training for some of their employees, training providers must emphasise to owners/managers the immediate operational benefits associated with a skilled and trained workforce. For example, job-related training may remove a competitive constraint such as a skills gap created by technological change. Training providers must provide info rmation surrounding the costs and benefits associated with training provision. Only by showing employers the expected returns associated with training provision can training providers convince employers that training is an investment rather than a cost.

A number of caveats to the presented results must be noted. Most notably, the data collected during this study did not allow the ignorance and market forces explanations for the uneven provision of job-related formal training to be explicitly tested. Further, the cross-sectional nature of the data analysed in this study made inferring causation problematic (Hage and Meeker, 1988; Huselid and Becker, 1996). For example, it is equally plausible that org anisations actively involved in providing training for some of their employees may be more likely to offer graduate student placements. T he direction of causality between the provision of training and participation on a formal/structured g raduate student wo rk ex perience prog ramme (GRA DUAT E), therefo re, warrants additional research attention.

T his study explored the provision of training by employers with regard to a variety of explanatory variables. However, a number of potentially important explanatory variables related to the composition of the workforce (for example, race, gender, marital status, level of educational attainment and membership of a union) (Booth, 1991; Miller, 1994), the career aspirations of employees (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1994), the occupational composition (A bbott, 1993), the org anisational structure of a business (Goss and Jones, 1992) and the characteristics, attributes, education and ambitions of owners/managers (Gibb, 1996)) were omitted from this ex plo rato ry study. Mo re refined models explaining the provision of formal training should therefore be developed which include a wider range of explanatory variables. T his exploratory study has also highlighted the need for cross-national research surrounding the factors associated with the provision of job-related training by employers. By replicating this study in a variety of national env ironments the w ider applicability (or generalisability) of this exploratory study’ main findings can be assessed.

A t a coarse industrial level of analysis, this exploratory study has confirmed

the assertion (Curranet al., 1993), that the nature and content of the goods and

IJEBR

4,3

208

to have provided planned on-the-job training (Model 2). It is, nevertheless, acknowledged that the industrial categories utilised in this study (and those frequently utilised elsewhere) were too broad to capture fine-level industry differences in the provision of formal training. A dditional research focusing on large and representative samples of firms engaged in a variety of industrial activities is still required to conclusively detect whether fine-level industry differences are important influencing the provision of various types of job-related formal training.

To develop more appropriate policies which encourage the provision of on-the-job and off-on-the-job formal training by employers further theoretical work needs to be conducted surrounding the triggers and the processes leading to the provision of general, transferable and specific training in SMEs as well as the barriers to training provision. A gg regate macro-level as well as micro-level research is required to ex plicitly to test the ig no rance o r market fo rces ex planations fo r the uneven prov ision of job-related fo rmal training by employers. Researchers should, in addition, explore the extent and factors associated with the provision of training provided by employers which has been taken up in the employees’ rather the employers’ time. T he extent and factors

associated with the take-up of informal training, induction training (Curranet

al., 1996), instrumental training (for example, training of a directly vocational or

technical nature) and sophisticated training (for example, the provision of programmes of a more developmental and innovative nature) (Goss and Jones, 1992) should receive additional research attention. Similarly, the extent and factors associated with the take-up of formal vocational training by employees at their own expense needs to be explored (Lynch, 1991; Stevens, 1994b). T he factors associated with the provision of training which results in a formal

qualification (Blundell et al., 1996; Curran et al., 1996) for the recipient also

warrants additional research attention. Further, the relationship between various types of formal training provision and/or the intensity of training provision (for example, the number of training schemes provided and/or the total hours spent on training prog rammes per hours worked) (Booth, 1991; Veum, 1996) and business performance need to be explored within a qualitative as well as a quantitative multivariate statistical framewo rk. A dditional research evidence will provide policy-makers with more accurate assessments of the direct and indirect benefits as well as the costs of a policy decision to encourage more SMEs to provide formal training for some of their employees. Finally, a key question which needs to be addressed is whether employers continue to provide job-related formal training for some of their employees once public subsidies have been removed.

Notes

Job-related

formal training

by employers

209

2. Determinants of formal training from the perspective of firms have been explored by A lba-Ramirez (1994) and Elias and Healey (1994). T he former study, however, only focused on firms with 200 or more employees, despite the fact that the majority of firms in Spain have less than 200 employees.

3. T his issue has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Marshallet al., 1995; Sto rey and Westhead, 1994; Westhead and Storey, 1996).

4. A notable exception to this trend is the Cambridge Small Business Research Centre (1992) study which explored the provision of training throughout the UK.

5. “From an exchange theory perspective, training may be viewed as an investment in the relationship between a company and a person and can contribute to an employee’s organizational commitment...Employees may view an effective training experience as an indication that the company is willing to invest in them and cares about them; thus, training may enhance their commitment to the organization” (Tannenbaumet al., 1991, p. 760).

6. For example, drawing on the work conducted by Noe (1986), Facteauet al. (1995, p. 3) identified three incentives for attending a training course: “...intrinsic incentives (the extent to which training meets internal needs or provides employees with growth opportunities), extrinsic incentives (the extent to which training results in tangible external rewards such as promotions, pay rises, and higher performance evaluations) and compliance (the extent to which training is taken because it is mandated by the organization)”.

7. Employers are less likely to provide “general” transferable skills training because of the difficulty of capturing the returns to training in the absence of deferred compensation sc hemes. A s a result, employers w ill be mo re likely to prov ide firm-specific non-transferable skills training (Elias, 1994). Further, employers are more likely to provide firm-specific training rather than general training (Hyman, 1992; OECD, 1991) without the need for government subsidies because the expenditure on firm-specific training accrues directly to the firm (Baldwinet al., 1995).

8. Greenhalgh and Mavrotas (1996) noted males working in small firms were more likely to move between workplaces than those employed in large firms.

9. A theoretical discussion surrounding the poaching externalities has been presented (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas, 1996; Stevens, 1994a, 1994b). Most notably, Stevens (1994a, p. 418) concluded, “W hen training is transferable, but the skilled labour market is not perfectly competitive, the private return to the training investment may be less than the social return. Furthermore, information asymmetry between employers and skilled workers may lead to inefficient matching of workers to firms....[T ]he nature of this second inefficiency is to increase the probability of the worker leaving the training firm and to exacerbate the difference between the private and social returns”.

10. Supporting A bbott (1993), Curranet al. (1993) have suggested that the nature and content of the goods and services provided by a firm can have an impact on the decision to provide training. In some knowledge-based sectors (A bbott, 1993; Curran et al., 1993), in part, due to resource constraints and/o r to max imise a firms immediate g row th potential (Wynarczyk et al., 1993) firms have recruited trained staff who had received their training in a higher education institute and/or received training during an apprenticeship which enabled them to respond to rapid rates of technological change (Steedmanet al. 1991). 11. In small firms w here the recruitment needs are very specific and focused,

owners/managers may prefer to recruit rather than to train existing employees (Hendryet al., 1991b).

12. Begg (1990, p. 359) noted skill shortages were more acute in prosperous regions and as a result “… it is difficult to argue a case for regionally differentiated training provision which is biased towards weaker regions”.

IJEBR

4,3

210

demographic characteristics of responding and non-responding ST EP businesses could not be statistically explored to detect any response bias.

14. Samples of non-responding and responding businesses to the follow-on questionnaire twelve months after the Shell Technology Enterprise Programme were compared for response bias (Westhead, 1997). For ST EP businesses, only one statistically significant difference emerged between respondents and non-respondents. Significantly more independent rather than subsidiary ST EP b usinesses responded to the follow -on questionnaire. However, no statistically significant differences emerged between non-responding and responding ST EP businesses with regard to the other “matching” criteria. Similarly, for non-ST EP businesses only one statistically sig nificant difference emerged between respondents and non-respondents. Responding non-ST EP businesses were significantly more likely to have been engaged at an industrial level in “other” activities (such as agriculture, forestry and fishing or construction) than non-responding non-ST EP businesses.

15. Johnson and Gubbins (1992, pp. 32-3) identified the following three reasons for the dominance of informal, firm-specific and on-the-job approaches to training in small businesses: “(i) in most cases this is the most appropriate means of introducing new recruits to the job. “Learning by doing” is seen as far more valuable than the theoretical approach which is thought to pervade college courses; (ii) small businesses do not have the resources to develop formalised, general training courses for internal provision. T he relatively small number of people involved make it an uneconomical proposition to move towards formal schemes; (iii) external courses are seen as too costly (in cash and time) and/or too general. Given that most b usinesses have their ow n “ idiosy ncrasies” , college courses are unlikely to prov ide appropriate training”.

16. Elias and Healey (1994) explored the extent, nature and determinants of job-related formal training in the City of Coventry in the West Midlands of England. T hey identified 6,080 establishments in this locality from British Telecom’s Connections in Business database. Out of this population, 2,993 establishments responded to a self completion questionnaire. T hree methods were used to g ather responses: 189 responses were obtained from face-to-face interv iew s (89 per cent response rate), 2,594 responses were obtained from a postal questionnaire (46 per cent response rate) and a further 210 responses were obtained from a telephone survey (77 per cent response rate). Overall, a 49 per cent response rate was achieved. Response rates, however, varied from 45 per cent of employers in the distribution sector to 70 per cent in the mineral extraction and metals sector.

17. A multinomial logit model was not utilised due to the independence of irrelevant alternatives proposition. T his technique assumes that a choice between two alternatives is independent of alternative dependent variable categories (Kmenta, 1986, p. 558).

18. Organisations which filed missing information returns to any of the explanatory variables listed in Table I were excluded from Models 1 to 6. For example, the 62 organisations which failed to state the absolute employ ment change in their businesses over the past year (EMPGROW) were excluded from the presented models.

19. Bannock (1991) asserted that the higher take-up of Business Growth Training (BGT ) option 3 (provided by the Training A gency) by firms in Scotland and the North, North West and West Midlands of England was primarily due to differences in the local delivery of BGT. He concluded, credible organisations with superior local networks with the local and regional business community not only raised awareness among SMEs of the prog ramme but also encouraged more firms to actively participate on the scheme.

Job-related

formal training

by employers

211

References

A bbott, B. (1993). “Training strategies in small service sector firms: employer and employee perspectives”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 4, pp. 70-87.

A ddison, J.T., and Siebert, W.S. (1994), “Vocational training and the European Community”,

Oxford Economic Papers,Vol. 46, pp. 696-723.

A lba-Ramirez, A . (1994), “Formal training, temporary contracts, productivity and wages in Spain”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 56, pp. 151-70.

A ltonji, J.G., and Spletzer, J.R. (1991), “Worker characteristics, job characteristics, and the receipt of on-the-job training”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review,Vol. 45, pp. 58-79.

A shenfelter, O. and Card, D. (1985), “Using the longitudinal structure of earnings to estimate the effect of training programs”, Review of Economics and Statistics,Vol. 67, pp. 648-60. Baldwin, J., Gray, T. and Johnson, J. (1995), Technology Use, T raining and Plant-Specific

Knowledge in Manufacturing Establishments, Statistics Canada, Ottawa.

Bannock, G. (1991), Change and continuity in small firm policy since Bolton, in Stanworth, J. and Gray, C. (Eds), Bolton 20 Years On: T he Small Firm in the 1990s, Paul Chapman, London, pp. 16-39.

Barron, J.M., Black, D.A . and Loewenstein, M.A . (1987), “Employer size: the implications for search, training, capital investment, starting wages, and wage g rowth”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 5, pp. 76-89.

Begg, I. (1990), “Training as an instrument of regional policy: the new panacea”, Regional Studies, Vol. 24, pp. 357-63.

Birley, S. and Westhead, P. (1990), “Growth and performance contrasts between ‘types’ of small firms”, Strategic Management Journal,Vol. 11, pp. 535-57.

Birley, S. and Westhead, P. (1992), “A comparison of new firms in ‘assisted’ and ‘non-assisted’ areas in Great Britain”,Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, Vol. 4, pp. 299-338. Bishop, J.H. (1994), “T he impact of previous training on productivity and wages, in Lynch, L.M.

(Ed.), Training and the Private Sector: International Comparisons, T he University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp. 161-99

Blundell, R., Dearden, L. and Meghir, C. (1996), T he Determinants and Effects of Work Related Training in Britain, T he Institute for Fiscal Studies, London.

Booth, A .L. (1991), “Job-related formal training: who received it and what is it worth?”, Oxford Bulletin of Economic Statistics, Vol. 53, pp. 281-94.

Buechtemann, C.F. and Soloff, D.J. (1994), “Education, training and the economy”, Industrial Relations Journal,Vol. 25, pp. 234-46.

Cambridge Small Business Research Centre (1992), T he State of British Enterprise: Growth, Innovation and Competitive A dvantage in Small and Medium-Sized Firms, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Campanelli, P., Channele, J., McCauley, L., Renout, A . and T homas, R. (1994), Training: A n Explanation of the Word and Concept with an A nalysis of the Implications for Survey Design, Research Report Series No. 30, Employment Department, London.

Campbell, M. and Baldwin, S. (1993), “Recruitment difficulties and skill shortages: an analysis of labour market info rmation in Yo rkshire and Humberside” , Regio nal Studies, Vol. 27, pp. 271-80.

Curran, J., Blackburn, R.A ., and Woods, A . (1991), Profiles of the Small Enterprise in the Service Sector, Kingston University, Small Business Research Centre, Kingston-upon-T hames. Curran, J., Blackburn, R.A ., Kitching, J. and North, J. (1996), “Small firms and workforce training”,