Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:31

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Strategy Choices of Potential Entrepreneurs

Jeffrey W. Alstete

To cite this article: Jeffrey W. Alstete (2014) Strategy Choices of Potential Entrepreneurs, Journal of Education for Business, 89:2, 77-83, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.759094

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.759094

Published online: 17 Jan 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 424

View related articles

View Crossmark data

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.759094

Strategy Choices of Potential Entrepreneurs

Jeffrey W. Alstete

Iona College, New Rochelle, New York, USA

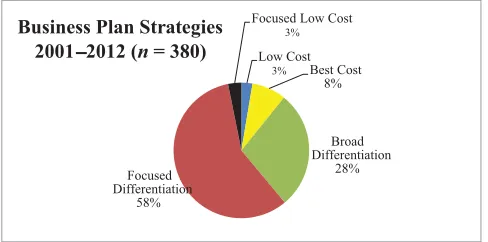

The author examined the written business plans of 380 students who completed courses in entrepreneurship and small business management over an 11-year period. An analysis categorized the plans into five generic competitive strategy types, and the results found that 58% chose a traditional, focused differentiation approach. A large portion (28%) used broad differentiation and a small number chose other generic strategies. When considering related literature on high failure rates of small businesses, the findings of this study suggest that potential entrepreneurs should be more informed about alternatives and consider combination strategies or flexible innovative approaches in new business endeavors.

Keywords: entrepreneurship, generic competitive strategy, Porter’s typology, small business plan, SME strategic planning

Many prospective future entrepreneurs and small business owners have ideas for potentially successful business ven-tures and a sincere passion for their ideas. Dreams of success, personal and monetary rewards, and freedom to make deci-sions and conduct themselves without traditional employer supervision are among the reasons people begin the process of planning a business. It has been stated that there are far more entrepreneurs than most people realize and the failure rate of new businesses is disappointingly high (Shane, 2010). This suggests that enthusiastic would-be entrepreneurs and others may often operate under a false set of assumptions. People seeking to start new ventures may also not realize the importance effective strategic planning, and how it can help new firms survive and grow (Kuratko, 2009). Reasons for lack of strategic planning have been identified, and in-clude time scarcity, lack of knowledge, lack of experience or skills, lack of trust or openness, and a perception of high cost (Porter, 1991). Today, there are many opportunities for peo-ple to find strategic planning information, including books, websites, talking with small business owners, small business development centers, or enrolling in college courses.

Courses on entrepreneurship and small business manage-ment are popular in higher education, and there are com-plete undergraduate and graduate degree programs available as well. Normally these courses and programs involve as-signments that require students to write a business plan that

Correspondence should be addressed to Jeffrey W. Alstete, Iona College, Hagan School of Business, 715 North Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801-1890, USA. E-mail: jalstete@iona.edu

enable potential entrepreneurs to specifically identify what needs to be done, and helps people move past the first ob-stacle of inaction (Katz & Green, 2011; Kuratko, 2009). The college and university faculty members who instruct students that are considering starting a small business need to be well informed regarding the sound ideas and starting points of small businesses, planning methodologies, marketing strate-gies, management and financial issues, and other important matters. In addition, private and publicly funded small busi-ness assistance agencies, investors, and others involved with new business ventures can benefit from further examination of strategic planning issues in small- and medium-sized en-terprises (SMEs). Therefore, the trends and results of recent small business planning proposals should be examined thor-oughly so that knowledgeable guidance can be offered to everyone involved in planning new business ventures.

A BRIEF REVIEW OF SELECTED RELATED LITERATURE

There are several established models or frameworks in the field of management that seek to identify different types of strategies that companies use or propose to use in competitive marketplaces. H. I. Ansoff (1965), Miles and Snow (1978), and Porter (1981) being among the most widely used by re-searchers, faculty, writers, consultants, and strategic planning practitioners. Igor Ansoff is known as the father of strategic management and developed a well-known product-market growth matrix tool to plot generic strategies for growing a business via existing or new products, in existing or new

78 J. W. ALSTETE

markets (I. Ansoff, 2008). The four elements of the Ansoff matrix are market penetration, market expansion, product expansion, and diversification. These four approaches can be used as labels for many business strategies in both small and large organizations. Miles and Snow’s theory of orga-nizational types holds that in order to perform excellently there must be a distinct connection between the mission and values of companies with their organizational strategy and functional strategies that involve their characteristics and be-havior (Kulzick, 2012). As a result of empirical research on the textbook industry, Miles and Snow developed their strate-gic framework of four classifications: defenders that focus on a narrow product-market segment, prospectors that continu-ally seek new market opportunities, analyzers that operate in a cost-efficient manner while sustaining an innovation focus, and reactors that stick to the current strategy and rarely make changes unless they are forced to do so by situational pres-sures. There have been research studies of businesses using and confirming the Miles and Snow typology, which found that prospectors are more common in firms employing under 100 people (O’Regan & Ghobadian, 2006). The Miles and Snow framework has been widely researched in other busi-ness studies to further validate the strategy types (Conant, Mokwa, & Varadarajan, 1990; McDaniel & Kolari, 1989; Snow & Hrebiniak, 1980; Zahra, 1987), and it should be noted that SME performance is likely to improve as they in-crease implementation of strategic planning and understand that innovative organizational cultures and strategies need to be aligned throughout the innovation process (Terziovski, 2010). In addition, combination strategies are also quite com-mon, have been found to be a viable choice for SMEs in the long run, and in at least one study outperform companies that follow a differentiation strategy (Leitner & Guldenberg, 2010).

Porter (1980) originally conceived a three-strategy ap-proach defined along two dimensions of narrow or broad market scope and strategic strength. Porter distilled his ideas into three best strategies: cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation. While the titles are generally self-explanatory, market segmentation has a narrow scope whereas cost leadership and differentiation have a primarily broad market spans. The Porter generic strategies have been researched widely in SMEs (Barth, 2003; D’Amboise, 1993; Leitner & Guldenberg, 2010; Pelham, 2000) and results vary and include many firms found to be using focused differentia-tion, broad differentiadifferentia-tion, and strategy types that are labeled as combined, hybrid, or mixed. Other research studies also have found “that SMEs commonly follow a focus strategy, with differentiation appearing to be the most popular com-petitive strategy used by SMEs in market niches” (Leitner & Guldenberg, 2010, p. 117; see also Gibcus & Kemp, 2003; Watkin, 1986; Weinstein, 1994). It was also noted in a pre-vious examination of the data from the companies analyzed that nearly all used a focus strategy and that approach was not seen as in need of further investigation. This statement

could support the need for further examination of the focused generic strategy type in SMEs to validate previous findings by researchers in the fields of entrepreneurship, strategic man-agement, and business education.

As mentioned, in recent years hybrid approaches have be-come popular concepts that combine strategy types, and some leading authors on strategic management have proposed an expanded version of the classic three-strategy proposed by Porter (1979, 2008) into a Five Generic Strategy Model that is widely taught in college business strategy capstone courses and explained in textbooks. It is important to understand what characterizes each of these expanded five generic strategies and why some may be more appealing to business leaders than others in different competitive markets (Thompson, Pe-teraf, Gamble, & Strickland, 2012):

1. A low-cost provider strategy: striving to achieve lower overall costs than rivals on products than rivals on products that attract a broad spectrum of buyers. 2. A broad differentiation strategy: seeking to

differenti-ate the company’s product offering from rivals’ with attributes that will appeal to a broad spectrum of buy-ers.

3. A focused (or market niche) low-cost strategy: concen-trating on a narrow buyer segment and outcompeting rivals on costs, this being in position to win buyer favor by means of a lower-priced product offering.

4. A focused (or market nice) differentiation strategy: concentrating on a narrow buyer segment and outcom-peting rivals with a product offering that meets the spe-cific tastes and requirements of niche members better than the product offerings of rivals.

5. A best-cost provider strategy: giving customers more value for the money by offering upscale product at-tributes at a lower cost than rivals.

Being that this model includes the traditional three generic strategies by Porter and adds the updated concept that de-velops the model further by separating differentiation ap-proaches into broad, focused, and focused low cost, as well as adding a hybrid best-cost strategy, it is an appropriate choice for research in regard to potential application by en-trepreneurs and has been used by other researchers in regard to SME performance mentioned previously. It should also be noted that in addition to providing the theoretical basis for the five generic strategy types explored in this paper, Porter also outlines unintentional errors that can occur when en-trepreneurs apply specific strategies (Kuratko, 2009; Porter, 1991) and that these fatal visions include misunderstanding industry attractiveness, having no real competitive advantage, pursuing unattainable competitive position, compromising strategy for growth, and failure to explicitly communicate the venture’s strategy to employees. Strategic decisions are important for both large and small firms to decide the cor-rect course of action, and can mean the difference between

success and failure (Brouthers, Andriessen, & Nicoloes, 1998). A research investigation such as the one conducted in this study could add informative findings to scholarly discus-sions in fields of entrepreneurship and strategic management regarding different frameworks for envisioning, planning, and implementing new business ventures.

METHODOLOGY

There have been ongoing conversations in the public arena and academe regarding the value of academic research (Mexal, 2011) as well as debates regarding rigor and rel-evance. Critics often question the usefulness of published research and state that findings are often based on methods that are unsuitable to the applied nature of professional disci-plines (Benbasat & Zmud, 1999; Davenport & Markus, 1999; Klein & Rowe, 2008; Mohrman, Gibson, & Mohrman, 2001; Moisander & Stenfors, 2009; Nicolai & Seidl, 2010). It has also been recommended that practitioners should be the focus of developing theories and concepts (Putnam, 1995; Rorty, 1998) and that the scholarship of teaching and learning is im-portant (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness [AACSB], 2012; Boyer, 1990). Opportunities for social science research in areas such as business education have developed in recent decades, allowing researchers and schol-ars to utilize the perspectives of students in higher education who will soon be working in business. Scholars can leverage their access to these individuals for use in research activities in ways that allow examinations of learning projects and stu-dent activities to expand the knowledge base in many fields of study (Loyd, Kern, & Thompson, 2005). By examining student learning assignments, this research methodology can help to reduce the supposed separation of student learning practices and controlled academic research. This approach is becoming more widely used and published together with traditional primary and secondary research, including labo-ratory and field-based investigations. In addition, it should be noted that the use of student assignments in college courses for qualitative research studies have been published in pre-vious peer-reviewed research articles in scholarly academic journals. As in other methodologies, readers should be aware that this type research has limitations, including but not lim-ited to, the nature of the research participants who are self-selected by choosing to enroll in these online undergraduate and graduate business courses offered at this particular col-lege, the limited knowledge and practical experience of the participants in small business and entrepreneurial endeavors, the possible preferences of successful small businesses due to the demographic and geographic location of the study lo-cation, and the size of the study population. Nevertheless, written business plan assignment instructions are explained by instructors and emphasized in popular textbooks, which often contain completed business plan examples. Because a majority of the courses examined in this study include a com-bination of part- and full-time students, some of whom are

currently employed, and have recently completed business core courses as part of their educational programs, the selec-tion of students in these courses can be considered measures that meet conditions of criterion sampling. Established quali-tative research concepts state that criterion sampling can add valuable elements to academic research and aid in attaining more precise study results for analysis due to the selection of cases that are chosen to meet the predetermined condition (Patton, 1990).

During the period from the fall semester of 2001 to win-ter trimeswin-ter 2011–2012 there were 22 course sections of entrepreneurship and small business management courses offered at a medium sized private college in the New York Metropolitan area that is regionally accredited and also holds specialized accreditation by AACSB-International. Eleven of the courses were electives in the graduate level master of busi-ness administration program, and the remaining 10 courses were electives in the undergraduate baccalaureate degree pro-gram. The course requirements for during the 11-year period were the same and included a written business plan as an important project. Students are required to obtain instructor approval for the business plan topic on an asynchronous on-line discussion board prior writing the paper. This is to ensure that appropriate business ideas are chosen and that only legal, ethical and moral business ventures are planned. The expec-tations are somewhat higher for the graduate-level business students, and the graduate courses included additional as-signments including a group project that involves creating an online e-business to produce revenue during the term of the course. The written business plans were not required to be re-lated to the group project, but a very small number of students in the 11 graduate courses over the 11-year period did choose to write their individual plan for the e-business team assign-ment. Another potential influence on student business plans is that a small portion of the participants in the study decided to write plans for businesses that their family or friends were about to begin or were already in operation for a short-time. However, this number was also very small and the researcher believes it did not greatly influence the findings.

The identification of the strategy types was based on the researcher’s extensive experience in teaching a capstone col-lege course on business policy and strategy for many years that includes Porter’s five generic strategy types. The re-searcher also authored previous articles in peer-reviewed journals on competitive business strategy as well as en-trepreneurial typologies (Alstete, 2002; Alstete & Halpern, 2008; Alstete & Meyer, 2011). The written student business plans were read individually one at a time and classified based on the aforementioned classifications from the estab-lished literature in the field.

RESULTS

In reading the 380 written business plans, I was able to iden-tify which of the five generic strategies that the potential

80 J. W. ALSTETE

Low Cost 3% Best Cost

8%

Broad Differentiation

28% Focused

Differentiation 58%

Focused Low Cost 3%

Business Plan Strategies 2001--2012 (n = 380)

FIGURE 1 Business plan strategy types (color figure available online).

future entrepreneurs and small business owners are seek-ing to use in the plans. Many of the written business plans in this study include strategy terminology in the executive summary, vision statement, company description, or mar-keting section that made identification of the strategy clear. However, an identifiable strategy was not clear in some of the written plans, or could be more appropriately labeled or classified in one or more of the typology systems such as Miles and Snow (defenders, prospectors or reactors) or H. I. Ansoff (market penetration, market expansion, product ex-pansion, or diversification). Nevertheless, I made decisions on some of the less clear classifications based on which of the five expanded Porter generic strategy types the business plan idea more closely resembles. Even with this limitation, it was obvious that by far the most common strategy planned is focused (market niche) differentiation (58%). Whether the business idea is for a restaurant, service business, new prod-uct, retail store, technology company, or another venture, the plans most commonly seek to concentrate on a constricted buyer division and out perform competitor companies by offering niche customers specialized characteristics that sat-isfy their preferences better than rivals in the marketplace.

After this finding, it was not surprising to learn that the sec-ond most common generic competitive strategy planned for is broad differentiation (28%). These students and poten-tial small business owners seek to distinguish their business ventures in ways that they believe will appeal to a broad spec-trum of customers. Often with a large selection of products or range of services that competitors do not offer. The results of the analysis for all five generic types during the 11-year study period are shown in Figure 1.

Interestingly, in today’s competitive business environ-ment, high unemployenviron-ment, and lower consumer spending and confidence, very few business plans in this study sought to use a low-cost (3%) or focused low-cost (3%) generic busi-ness strategy. In general the ideas contained in the busibusi-ness plans seem to state that their owners will be able to pro-vide sufficient differentiation (either focused or broad using the expanded Porter typology) so that consumers will use that reason to spend money for the product or service pro-posed. Also somewhat surprising is the finding that only 8% of the business plans were classified as a best-cost strategy, where the approach is to offer customers more value for their purchases by combining good-to-excellent service or prod-uct features at a relatively lower cost than competitors offer. From a broad perspective in looking at the economy today, the idea of targeting lower or best costs and prices for busi-ness services or products with similar features also would seem to be appealing in marketplaces with dwindling discre-tionary spending and other negative factors in the economy. However the written business plans of the potential student entrepreneurs in this study clearly sought differentiation in their strategy, with focused differentiation being the most common throughout the 11-year period and broad differen-tiation the second most popular choice.

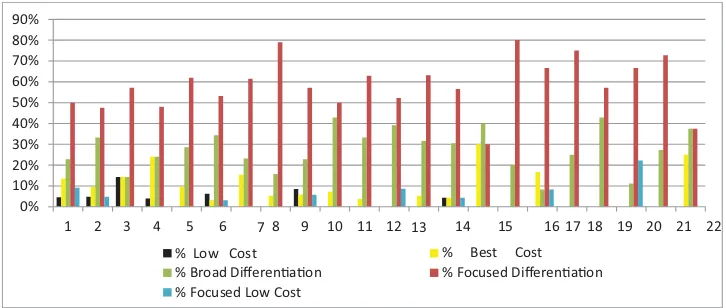

Figure 2 illustrates the comparison of strategies planned over the 11-year time period.

There was only one brief period when broad dif-ferentiation outnumbered focused difdif-ferentiation (winter

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

Broad Differentiation Focused Differentiation

FIGURE 2 Comparison of focused and broad differentiation strategies, 2001–2012 (color figure available online).

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

% Low Cost % Best Cost

% Broad Differenaon % Focused Differenaon

% Focused Low Cost

FIGURE 3 Summary of all five classifications 2001–2012 (color figure available online).

2007–2008), and this may have been a normal variation due to the nature of the entrepreneurship course which happens to be a graduate level course that is offered annually in a win-ter trimeswin-ter (12 weeks) format. Overall, the findings show that focused and broad differentiation was the most common theme, when combined (58% or 28%) add up to a very large 86% of the proposed generic strategy types. This could in-dicate that student understanding of concepts regarding the larger macroeconomic environment issues and other strategy types available may need to be improved in course materials and by faculty instruction. Also, when looking for business ideas or aspects of plans related to globalization or interna-tional business, nearly all of the 380 business plans examined did not specifically plan for current and future expansion be-yond local and regional markets. However a small number of business ideas that involved a product or service did men-tion the possibility of selling to internamen-tional markets, and large number of the plans had international concepts such as foreign culture restaurants or specialized services for local American customers. The customers targeted are often im-migrants who would want a food or product from their home culture, or American customers for an international focused differentiated business. In addition, it should be noted that the findings here may indicate that some potential future en-trepreneurs may not be making a wise choice in choosing a differentiation strategy because previous research of SME firm performance found that combination strategies with no generic attributes have higher profitability and growth than firms that use a differentiation strategy (Leitner & Gulden-berg, 2010).

The overall summary findings during the 11-year period are shown in Figure 3. This figure shows that the strategy types did not vary greatly, and largely maintained the pre-dominance of broad and focused differentiation approaches for new small business proposals.

The evidence collected in this 11-year study about the preponderance of the traditional five generic strategy types in small business planning could remind readers of the

pre-viously mentioned warning by Porter regarding the uninten-tional errors that can happen when entrepreneurs apply spe-cific strategies. Those aforementioned fatal visions” about industry appeal, gaining competitive advantage over rivals, chasing unfeasible competitive positions, and other nega-tive consequences highlight the need for further discussion and investigation of what small business owners and new business entrepreneurs are planning in today’s challenging marketplace.

DISCUSSION

Overall the findings in this study regarding the usage of Porter’s focus or niching strategies support what is com-monly written about and suggested in books concerning small business (Kao, 1981; Kotler, 1996; Paley, 1989; Waterworth, 1987) because it is a common belief that SMEs need to identify an appropriate market niche that is attractive. The collegiate textbooks even provide criteria for defining the at-tractiveness of potential niche markets for SMEs and seem to imply that niching strategies are the only competitive strat-egy option available to SMEs given their lack of resources (Brown, 1995; Lee, Lim, & Tan, 1999; Thompson et al., 2012). Therefore due to the high failure rate of new busi-nesses mentioned previously (Shane, 2010) and the options for other ways to craft strategies, faculty and textbook writers should inform potential entrepreneurs and new small busi-ness owners that there are alternatives to focused and broad differentiation strategies. Perhaps there should be additional emphasis (following the macroenvironmental and competi-tor analyses that are normally conducted when planning a new business) that business plan writers should consider a thoroughly reasoned strategic plan type that has a greater likelihood of success based on clear linkage to the analyses. Miles and Snow, H. I. Ansoff, or adaptive nontraditional types of strategies could be considered. If not just for the reasoned

82 J. W. ALSTETE

analyses, also for the examination of previous SME success-ful examples (albeit few percentage that they are) and that the selection of focused and broad differentiation approaches have, in various studies, generally been shown not to be suc-cessful for many endeavors. It has been proposed that some entrepreneurs may in fact spend too much time planning and should take small, rapid steps to get initiatives started. A recent depth study of 27 serial entrepreneurs found that in-stead of beginning with a predetermined goal, these success-ful entrepreneurs allow opportunities to emerge and focus on maximizing returns as an alternative to seeing a perfect solution (Schlesinger, Kiefer, & Brown, 2012). Therefore potential entrepreneurs may need to think in different ways than those that are taught in traditional entrepreneurship and strategic management frameworks. In fact, it has been known for quite a while that only a small portion of entrepreneurs get their ideas from systematic research (4%) and the majority (71%) replicated or modified an idea encountered from pre-vious employment or was discovered serendipitously (20%; Bhide, 1994). The results of the study in this article that potential future entrepreneurs are still following traditional focused and broad differentiation and that other studies have found the success rate of entrepreneurial endeavors to still be relatively low means that educators, investors, small business development centers, and others need to be better informed about alternatives and to think outside traditional strategy constructs.

CONCLUSION

The findings here reveal that a majority of the potential fu-ture entrepreneurs are seeking to strategically position their new businesses in the traditional focused or broad differentia-tion categories. Based on the high failure rate of new business ventures, and previous research of successful SME strategies, it can be concluded that a wider choice of strategy options should be made available to people and organizations in-volved in writing business plans. Courses and programs in en-trepreneurship should examine and explain alternatives to the traditional five generic strategy types, particularly those aside from focused differentiation and broad differentiation. Com-bination strategies and modern innovation-oriented strategies that seek to create new market space by using a systematic approach to creating value innovation, or more free-form cre-ative thinking, may be better able to assist new SMEs succeed against competition from their peers and larger competitors with more resources. It is recommended that additional re-search should be conducted that follows up on the findings presented in this article regarding what strategies planned by entrepreneurs and small business owners for actually ac-complish when implemented, if the strategies change, and what the effective approaches to managing strategic change should be emphasized for SMEs today. In this rapidly chang-ing global marketplace with new technology, increased

com-petition, new government regulations, changing employee and customer demographics, and other factors that challenge SME owners, a proper understanding of all strategic plan-ning options should be an expected part of developing and growing businesses.

REFERENCES

Alstete, J. W. (2002). On becoming and entrepreneur: An evolving typol-ogy.International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research,8, 222–234.

Alstete, J. W., & Halpern, D. (2008). Aligning knowledge management drivers with business strategy implications.Journal of Knowledge Man-agement Practice,9(3), 1–14.

Alstete, J. W., & Meyer, J. P. (2011). Expanding the model of competi-tive business strategy for knowledge-based organizations.International Journal of Knowledge and Management,9, 16–21.

Ansoff, H. I. (1965).Corporate strategy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Ansoff, I. (2008).Ingor Ansoff: The father of strategic management.

Re-trieved from http://www.easy-strategy.com/igor-ansoff.html

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2012).

Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accredita-tion. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/accreditation/standards-busn-jan2012.pdf

Barth, H. (2003). Fit among competitive strategy, administrative mecha-nisms, and performance: A comparative study of small firms mature and new industries.Journal of Small Business Management,41, 133–147. Benbasat, I., & Zmud, R. W. (1999). Empirical research in information

systems: The practice of relevance.MIS Quarterly,23, 3–16.

Bhide, A. (1994). How entrepreneurs craft strategies that work.Harvard Business Review,72, 150–161.

Boyer, E. L. (1990).Scholaship reconsidered: Priorities of the professo-riate. Princeton, NJ: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Brouthers, K. D., Andriessen, F., & Nicoloes, I. (1998). Driving blind: Strategic decision-making in small companies.Long Range Planning,

31, 130–138.

Brown, R. (1995).Marketing for small firms. London, England: Holt, Rein-hart & Winston.

Conant, J., Mokwa, M., & Varadarajan, P. (1990). Strategic types, distinctive competencies, and organizational performance.Strategic Management Journal,11, 365–383.

D’Amboise, G. (1993). Do small business manifest a certain strategic logic? An approach for identifying it.Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship,11, 8–17.

Davenport, T. H., & Markus, L. (1999). Rigor vs. relevance revisited: Re-sponse to Benbasat and Zmud.MIS Quarterly,23, 19–23.

Gibcus, P., & Kemp, R. G. M. (2003). Strategy and small firm per-formance (EIM SCALES research report H20028). Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/eim/papers/h200208.html

Kao, R. W. Y. (1981).Small business management: A strategic emphasis. Toronto, Canada: Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

Katz, J. A., & Green, R. P. (2011).Entrepreneurial small business. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Klein, H. K., & Rowe, F. (2008). Marshaling the professional experience of doctoral students: A contribution to the practical relevance debate.MIS Quarterly,32, 675–686.

Kotler, P. (1996).Marketing management: Analysis, planning, implementa-tion, and control(9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hail. Kulzick. (2012). Miles and Snow organizational types. Retrieved from

http://www.kulzick.com/milesot.htm

Kuratko, D. F. (2009).Entrepreneurship: Theory, process, practice(8th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Lee, K. S., Lim, G. H., & Tan, S. J. (1999). Dealing with resource dis-advantage: Generic strategies for SMEs.Small Business Economics,12, 299–311.

Leitner, H.-H., & Guldenberg, S. (2010). Generic strategies and firm per-formance SMEs: A longitudinal study of Austrian SMEs.Small Business Economics: An Entrepreneurship Journal,35, 169–189.

Loyd, D. L., Kern, M. C., & Thompson, L. (2005). Classroom research: Bridging the ivory divide.Academy of Management Learning & Educa-tion,4, 8–21.

McDaniel, S., & Kolari, W. (1989). Marketing implications of Miles and Snow’s strategic typology.Journal of Marketing,51, 19–30.

Mexal, S. J. (2011, May 22). The quality and quantity in aca-demic research. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/The-Quality-of-Quantity-in/127572/ Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978).Organizational strategy, structure, and

process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Mohrman, S. A., Gibson, C. B., & Mohrman, A. M. (2001). Doing research that is useful to practice: a model of empircal exploration.Academy of Management Journal,44, 357–375.

Moisander, J., & Stenfors, S. (2009). Exploring the edges of theory-practice gap: Epistemic cultures in strategy-tool development and use. Organisa-tion,16, 227–247.

Nicolai, A., & Seidl, D. (2010). That’s relevant! Different forms of practical relevance in management science.Organisation Studies,31, 1257–1285. O’Regan, N., & Ghobadian, A. (2006). Perceptions of generic strategies of small and medium sized engineering adn electronics manufacturers in the UK: The applicability of the Miles and Snow typology.Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management,17, 603–620.

Paley, N. (1989).The manager’s guide to competitive marketing strategies. New York, NY: Free Press.

Patton, M. Q. (1990).Qualitative evaluation and research methods(2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pelham, A. M. (2000). Market orientation and other potential influences on performance in small and medium-sized manufacturing firms.Journal of Small Business Management,38, 48–67.

Porter, M. E. (1979). How competitive forces shape strategy. Harvard Busi-ness Review,57, 137–145.

Porter, M. E. (1980).Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing indus-tries and competitors. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (1981).Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining su-perior performance. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (1991, September). Knowing your place: How to assess the attractiveness of your industry and your company’s position in it.Inc., 90–94.

Porter, M. E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Har-vard Business Review,86, 78–93.

Putnam, H. (1995).Pragmatism: An open question. Oxford: Blackwell. Rorty, R. M. (1998).Truth and progress. New York, NY: Cambridge

Uni-versity Press.

Schlesinger, L. A., Kiefer, C. F., & Brown, P. B. (2012). New project? Don’t analyze—Act.Harvard Business Review,82, 154–158.

Shane, S. A. (2010).The illusions of entrepreneurship: The costly myths that entrepreneurs and policy makers live by. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Snow, C., & Hrebiniak, L. (1980). Strategy, distinctive competence, and organizational performance.Administrative Science Quarterly,25, 317–336.

Terziovski, M. (2010). Innovation practice and its performance implications in small and medium enteprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector: A resource-based view.Strategic Managemetn Journal,31, 892–902. Thompson, A. A., Peteraf, M. A., Gamble, J. E., & Strickland, A. J., III.

(2012).Crafting and executing strategy: The quest for competitive ad-vantage. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Waterworth, D. (1987).Marketing for small business. Basinstoke, England: Macmillian.

Watkin, D. G. (1986). Toward a competitive advantage: A focus strat-egy for mail retailers. Journal of Small Business Management, 24, 9–16.

Weinstein, A. (1994).Market segmentation: Using demographics, pscycho-graphics, and other niche marketing techniques to product and model customer behavior. Chicago, IL: Probus.

Zahra, S. (1987). Corporate strategic types, environmental perceptions, man-agerial philosophies, and goals: An empirical study.Akron Business & Economic Review,18, 64–77.