www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Space use and agonistic behaviour in relation to sex

composition in large flocks of laying hens

K. Oden

a,), K.S. Vestergaard

b,†, B. Algers

a´

a

Department of Animal EnÕironment and Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Swedish UniÕersity of

Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 234, SE-532 23 Skara, Sweden

b

Department of Animal Science and Animal Health, Royal Veterinary and Agricultural UniÕersity,

8 Gro/nnegards˚ Õej, DK-1870 Frederiksberg C, Denmark

Accepted 30 November 1999

Abstract

Some authors have found indications of subgroup formation when domestic fowl are forced to live together in large flocks, while others have not. In this study experiments were carried out to test the hypothesis that hens in large flocks have home ranges in parts of the pen and that they

Ž

form subgroups. We also studied if this is influenced by males. In a tiered aviary system density

2 .

averaged 16 hensrm of floor area eight flocks of 568"59 ISA Brown laying hybrids were kept

Ž .

in pens. Half of the pens contained 1 male per on average 24 females mixed flocks . At peak

Ž .

production 36–53 weeks of age four females roosting closely together for about 14 days and four females roosting far apart from each other were taken out from each flock and put together in separate groups in small pens. Their agonistic behaviour was studied for 2 days before they were put back. This was repeated with new birds, resulting in 16 small sample groups being studied. At 70 weeks, three groups of 10 females per flock roosting closely together in different parts of the pen were dyed with different colours and their locations were observed for 2 nights and 2 days. The incidence of aggressive pecks during day 1 among birds that had been roosting close to

Ž .

each other tended to be lower Ps0.05 than among birds that had been roosting far apart. This effect was not significant among birds from all-female flocks, but among birds from mixed flocks

ŽP-0.05 . However, this indicates a recognition of roosting partners and possibly also a rebound.

effect of the males’ reduction of female aggressiveness towards strangers. Irrespective of sex

)Corresponding author. Present address: Nedre Bergsgatan 10, SE-553 38 Jonkoping, Sweden. Tel.:¨ ¨ q46-36-16-86-34; fax:q46-36-16-86-34.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] K. Oden .´

†

Deceased 16th November 1999.

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

composition in the flocks, birds marked while roosting at the ends of the pens were significantly more often observed within these areas than in other areas of the pen during daytime and came

Ž .

back to the same roosting sites at night P-0.05–P-0.001 . This was not the case for birds from the middle of the pens, where the distribution in the pen in most cases did not differ from random. These results show that laying hens in large groups are rather constant in their use of space, which indicate the presence of home ranges. However, environmental features that facilitate localisation may be important. In summary, we think that these findings indicate the existence of subgroup formation.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Chickens; Spatial utilization; Agonistic behaviour; Sex composition

1. Introduction

In a natural habitat, feral fowl and red jungle fowl form groups and stay within a

Ž . Ž

certain area, the home range or territory if defended , and a constant roosting site if

. Ž .

undisturbed . In red jungle fowl Collias and Collias, 1967 or feral domestic fowl ŽMcBride et al., 1969 , the home ranges become territories in the breeding season and. are actively defended by the dominant males, which is also a well-known behaviour in

Ž .

fowl that are housed and cared for by humans e.g., McBride and Foenander, 1962 . The Ž

dominance is connected to the ‘‘personal sphere’’ of the male which is a kind of .

portable territory , a behaviour that is also expressed by subordinate males without fixed

Ž .

territories McBride et al., 1969 . However, territorial behaviour or personal spheres are not a uniquely male phenomenon. Broody hens defend the area around their chicks and

Ž .

Craig and Guhl 1969 found territorial behaviour in all-female flocks of domestic fowl ŽRhode Island Reds . They also found that the tendency for individual birds to stay and. be dominant within a certain area seemed to be stronger in flocks of 400 than in flocks of 200 birds.

In a large flock, a hen cannot recognize all other individuals, and some authors have found that hens in this situation tend to keep together in subgroups of well known birds ŽMcBride, 1964; Bolter, 1987; Grigor et al., 1995 . However, according to other studies,

¨

.Ž

hens in large flocks move around without any sign of subgroup formation Hughes et al., .

1974; Appleby et al., 1989 , although Appleby et al. mentioned that crowding strongly restricted the free movements of the hens.

Ž

Hens usually prefer the company of familiar birds Bradshaw, 1992; Appleby and

. Ž

Jenner, 1993; Dawkins, 1996 and show aggression towards unfamiliar birds Hughes, .

1977; Zayan, 1987a , which might lead them to form small groups of familiar birds

Ž .

within a large flock. Grigor et al. 1995 found that birds tended to avoid strangers more than both high-ranking and low-ranking familiar birds. They concluded that birds therefore might try to move within a restricted area to minimize the risk of meeting strangers. It is also very probable that social factors, like rank position, restrict the bird’s

Ž . Ž .

movements Craig and Guhl, 1969 . Gibson et al. 1986 for example, found that low-ranking individuals moved only over a restricted area as compared to high-ranking birds.

Ž

Female aggressiveness is reduced in the presence of males in small McBride, 1964;

. Ž

.

1999 groups of hens. Whether this effect is due only to their social dominance over the females or whether it can also be attributable to enhanced formation of subgroups or both, has so far not been clarified. For a cock, it is natural to gather hens and guard them

Ž .

against predators as well as other males McBride et al., 1969 . Therefore, it is likely that the presence of males in a flock would facilitate formation of subgroups. Widowski

Ž .

and Duncan 1995 reported clustering of female hens around the males in a flock of 50 females and 10 males. However, they could not identify any territorial subgroups.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether hens in large intensively housed flocks have home range areas, including a constant roosting site, that they tend to use more than other areas and whether roosting partners recognize each other as indicated by a lower incidence of aggressiveness than among birds that roost far apart. Based on the behaviour of free living hens, recognition of roosting partners and existence of home ranges are two important prerequisites for subgroup formation. Since males of feral fowl are very active in defending their territory, a further aim was to study whether or not

Ž .

males had any influence on these parameters. The hypotheses to test were: 1 that birds would not move over the available area at random but rather tend to stay more within

Ž .

certain parts of it than within others; 2 that they would constantly use a specific Ž .

roosting site at night; and 3 that birds using the same roosting site would be less aggressive towards each other as compared with birds roosting far away from each other in the pen. A fourth hypothesis was that hens from mixed flocks would show the above three behavioural indications to a higher degree than hens from single-sexed flocks.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and housing

Eight groups of ISA Brown laying hybrids were studied in two replicates of four, with each replicate having two all female and two mixed groups. The birds were housed in large pens in a tiered aviary system. Group sizes ranged from 505 to 634 birds per pen and density was 16"1 birdsrm2 of floor area. The mixed groups contained 1 male per 24"2 females. The study was carried out over 2 years, with a replicate per year. During the second year, the groups, due to a decision by the owner, also consisted of 50% Shaver 288 white females. To be comparable to the first year, only data from ISA Brown birds were collected. All animals came from the same breeder and were brought up together each year. All groups were kept in the same house on the production farm.

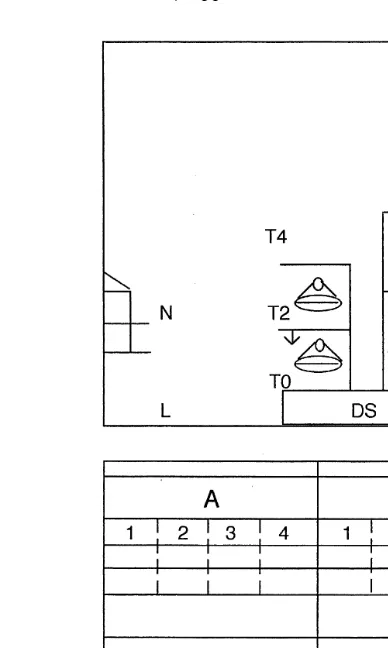

Ž .

Ž

Fig. 1. Cross section and plan of the system. T0–T5 indicate the different tiers with feeding pans, nipple

.

drinkers and perches , Nsnests, Lslittered floor, DSsdung scrapers. A–D are the four pens used with the sections numbered.

was 16.5 cm. The temperature was 23"68C and the photoperiod was 14 L:10 D, with a light intensity ranging from 7 to 20 lx.

2.2. ObserÕations in the home pens

At 70 weeks of age in both years, three groups of 10 females sitting closely together Žshoulder by shoulder during their night roost, about 2 h after the beginning of the dark. period, were dyed with either green or blue or both colours, using crayons for sheep

Ž .

marking. In each pen, one group on the tiers T1 or T0 Fig. 1 near each end and one in the middle of the pen were coloured. The birds were observed during the 2 following days and nights. Number of coloured birds per section was recorded once per hour for 9

Ž .

2.3. Studies of small sample groups

Between week 36 and 53, which is at the peak of egg production, during year 2,

Ž .

about 10 ISA Brown females per pen roosting closely together shoulder by shoulder at night were marked with coloured leg-rings. Four of these marked birds still roosting together after 10–14 days were randomly picked out at night, individually marked by

Ž .

adding leg-rings and put together the ‘‘close’’ group in a littered pen of 1=1=1 m. Ž

At the same time, four birds that were roosting far apart from each other i.e., )2 tiers

. Ž

and 1 section away, one from each of the fourrfive sections were picked out the .

‘‘apart’’ group , marked with leg-rings and put in another pen. The pens contained four individual nests, 1-m perch space, two food cups, two water cups and wood-shavings as litter. They were placed next to each other in a room adjacent to the one that housed the larger pens. This anteroom was lighter, but the test pens were shielded off so that they

Ž .

had the same light intensity 7–20 lx as in the large pens. The groups in the two pens could hear, but not see each other.

This procedure with one ‘‘close’’ group and one ‘‘apart’’ group was repeated every fortnight with either birds from mixed flocks or with birds from single-sexed flocks Žbalanced . When all four large pens were done, a new round was started, with new. birds, resulting in a total of 16 small sample groups; eight from pens with all-female flocks and eight from pens with mixed flocks.

Ž

All agonistic behaviour in the group aggressive pecks — severe pecks at the anterior part of the body, threats — including stretching the neck, ruffling neck feathers and displaying the side, and avoidances — including turning away the head, withdrawing,

Ž ..

freezing, squatting, crouching and fleeing Oden et al., 1999

´

as well as gentle andŽ .

severe feather pecks Vestergaard, 1994 were recorded. The performer and recipient of

Ž .

each behaviour were identified. Each observation lasted for 2 days 2=9 h starting half an hour after the onset of the light period each day. Each group was watched for 20 min, then there was a 10-min break before the other group was studied and so on, resulting in eighteen 20-min observations periods per group. For ethical reasons, as high levels of aggression could be expected to occur, the animals in the small groups were supervised constantly during the light period and also when they were put back into the large flocks to ensure their well-being.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Ž

To determine if the location as defined by the section recorded and calculated as .

mean percentage of observations per day of the coloured birds differed from the Ž random distribution, we used chi-squared tests with 3 and 4 degrees of freedom df ; the

.

pens had 4 or 5 sections . Because of the number of tests performed and the risk for mass significance, the comparisons marked withU

andUU

cannot be considered strictly significant. However, those comparisons with a P-value less than 0.001 indicate that the location of the birds differ significantly from a random distribution. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Roosting site constancy over 2 nights and the tendency to stay during daytime within the same section as was

Ž . 2

used during the night roost ns16 end groups, 8 middle groups .x -values in brackets Penryear Composition Night roost constancy Daytime location

end gr I middle gr end gr II end gr I middle gr end gr II

Cr2 single-sexed 35.4 NS 31.0 40.8 11.0 NS

UU UUU U UU

NSsnot significant, Chi-square-analysis per group with 3 df for tests in pens A and D, and 4 df for tests in pens B and C. A small P-value indicates that the distribution differs significantly from a random distribution

Žsee also Section 2.4 ..

U

P-0.05.UU

P-0.001.UUU

P-0.01.

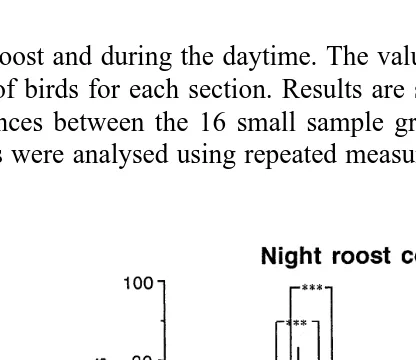

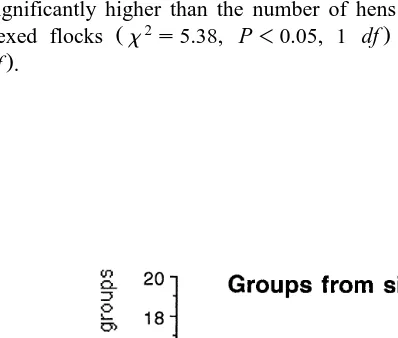

the night roost and during the daytime. The values were calculated as mean percentages per night of birds for each section. Results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Differences between the 16 small sample groups in the frequencies of the recorded behaviours were analysed using repeated measures ANOVA. The values for the nine 20

Ž .

Fig. 2. The percentage of birds observed roosting in the same section and tier as they were marked in,

Ž .

adjacent section and most distant section, respectively. Values are means "SEM for two end groups and one

Ž .

middle-group per flock four single-sexed and four mixed flocks observed at 2 nights. The mean percentage for each group was used in the chi-squared test. The test showed that the number of hens roosting in ‘‘same’’ section was significantly higher than the number of hens roosting in ‘‘adjacent’’ section both for end-groups

Ž 2 . Ž 2

from single-sexed flocks x s34.47, P-0.001, 1 df and end-groups from mixed flocks x s46.98,

.

Fig. 3. The percentage of observations of birds during daytime in the same section as they were marked in,

Ž .

adjacent section and most distant section, respectively. Values are means "SEM for two end groups and one

Ž .

middle group per flock four single-sexed and four mixed flocks observed for 2 days. The mean percentage for each group was used in the chi-square test. The test showed that the number of hens found in ‘‘same’’ section was significantly higher than the number of hens found in ‘‘adjacent’’ section both for end-groups

Ž 2 . Ž 2

from single-sexed flocks x s5.38, P-0.05, 1 df and end-groups from mixed flocks x s3.93,

.

P-0.05, 1 df .

Ž .

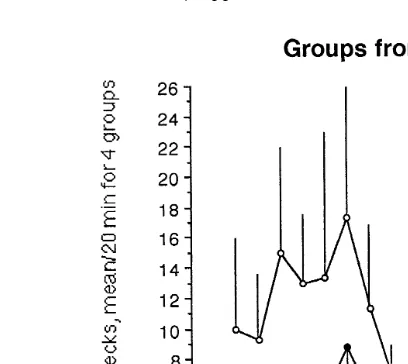

Fig. 4. The frequency of aggressive pecks over a 2-day period nine 20-min observations per day in small

Ž .

sample groups from all-female flocks. The values shown are the mean number "SEM of aggressive pecks

Ž .

per 20 min for four groups of birds picked out roosting closely together ‘‘close’’ and four groups of birds

Ž .

picked out roosting far apart from each other ‘‘apart’’ . The values from day 1 are used in a repeated measure

Ž .

Ž .

Fig. 5. The frequency of aggressive pecks over a 2-day period nine 20-min observations per day in small

Ž .

sample groups from mixed flocks. The values shown are the mean number "SEM of aggressive pecks per

Ž .

20 min for four groups of birds picked out roosting closely together ‘‘close’’ and four groups of birds picked

Ž .

out roosting far apart from each other ‘‘apart’’ . The values from day 1 are used in a repeated measure ANOVA. The test showed a significant difference between the ‘‘close’’ and the ‘‘apart’’ groups from mixed

Ž .

flocks Fs6.13, dfs1 and 6, P-0.05 .

min-periods day 1 in the experiment were used to test the difference between the

Ž .

treatments ‘‘close’’ and ‘‘apart’’, using eight groups per treatment Altman, 1994 . The results are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Statistics in both experiments were performed using

Ž .

Statview for Macintosh, Version 1.0 .

3. Results

3.1. Space use and constancy of night roosting site

As shown in Table 1, groups from the ends of the pens used the same roosting site Žtier and section at night significantly more than random. Many end groups also stayed. significantly more within the sections that they were marked in during the daytime. However, groups from the middle of the pens generally did not. The pattern was about the same regardless of the sex composition in the pens: in seven of the pens nearly all end group birds used the same roosting site during the 2 consecutive nights. In seven of the eight pens, birds from either one or both end groups stayed significantly more often during daytime in the section they were marked at night than could be expected by chance.

Ž .

We also compared roosting both nights in the same roosting site with roosting in the

Ž .

adjacent section and most distant section Fig. 2 . Regardless of sex composition in the Ž

flocks, most birds from end-groups used the same roosting sites both nights single-sexed, .

much less consistent in their choice of roosting site. A similar analysis of the daytime locations showed that the sections of the night roost were used significantly more than

Ž

other sections during the daytime by end group birds single-sexed, P-0.05, mixed,

. Ž .

P-0.05 ; but again for mid-pen groups, this was not the case Fig. 3 .

3.2. Aggression in small sample groups

The results show that during the observations the first day, there were significantly Ž less aggressive pecks in ‘‘close’’ groups than in ‘‘apart’’ groups from mixed flocks Fig.

.

5, P-0.05 . But in groups from single-sexed flocks, there was no significant difference ŽFig 4, Ps0.43 . When the data was pooled ss. Ž qm , there was a tendency for higher.

Ž

values in groups of birds that had been roosting far apart from each other Fs4.42, .

dfs1 and 14, Ps0.05 . There were no significant differences between groups during the second day.

There were no significant differences between the treatments in the numbers of threats, avoidances, gentle and severe feather pecks in all small sample groups from mixed flocks as compared to groups from single-sexed flocks.

In the sample investigated in this report, there were more performers of aggressive Ž

pecks in day 1 as compared to day 2 mean number in ‘‘close’’ groups: 2 compared to .

1.5, and in ‘‘apart’’ groups 2.5 to 1.5 . The mean number of performers in ‘‘apart’’ groups from mixed flocks were 2 compared to 1, whereas in ‘‘apart’’ groups from single-sexed flocks, the means were 3 compared to 2. Retaliations of the dominance order were evenly spread between the groups and over the days. No hypothesis testing was performed because of the small number of registrations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Localisation

Ž .

by McBride and Foenander 1962 . Even for hens in a natural habitat, localisation may

Ž .

be difficult if they cannot rely on well-known environmental clues. Collias et al. 1966 found no signs of a homing ability in red jungle fowl transferred 300–400 m from their home territory.

4.2. Reduced aggression

During the first day together, one would expect a higher incidence and more performers of aggression in groups of unacquainted birds than in groups of birds that know each other. This was also the case in this study, though no hypothesis testing was performed on the number of performers. The difference in aggressiveness was signifi-cant in groups from mixed flocks but not in groups from all-female flocks, and the results therefore indicate that the males had an effect. The reducing effect of males on

Ž female aggression found in a previous study of laying hens in the large flocks Oden et

´

.

al., 1999 , however, seems to depend more on the fact that males dominate females socially by their immediate presence than an enhanced subgroup formation, as there was no overall lower level of aggressiveness in the small sample groups from mixed flocks. In fact, the higher aggressiveness among the unacquainted hens from mixed flocks when taken out and put together in small groups with restricted space might well be a rebound effect of the males’ influence.

During the second day, there were no significant differences between the groups,

Ž .

which is in accordance with the findings of Zayan 1987b that hierarchies in small groups of laying hens could be formed rather quickly. Zayan also discussed the idea that large groups are built up by subgroups and that information about aggressive encounters could be used transitively by the birds, which would explain the relative stability also in large groups.

Ž .

According to Lindberg and Nicol 1996b agonistic behaviour in semi-familiar and unfamiliar groups tends to be expressed by aggressive pecks, rather than by threats which are more commonly used in familiar groups. This means that birds that are acquainted to one another do not have to fight with each other for dominance. The present results are in accordance with this idea as there were no significant differences regarding threats but by aggressive pecks.

Ž .

Oden et al. 1999 found no significant difference in feather pecking between mixed

´

and single-sexed flocks, and also no less feather damage in mixed groups. This is in accordance with the results of the present study.

4.3. The method

Ž .

In the present study the different resources were unlike most situations in nature in close proximity to the hens in all parts of the pen, and consequently there was no need

Ž .

for them to move far about. McBride and Foenander 1962 found that the average area of movement of hens in a flock of 80 birds in captivity was about one third of the total

2 Ž .

available area, or 13 m . Furthermore, Collias and Collias 1967 found that jungle fowl in a semi-natural zoo habitat were more stable and persistent in their choice of night

Ž

roost site than wild ones. They also found that the zoo flocks of up to about 40 .

Ž .

of the territories Collias et al., 1966 . Therefore, the method of assigning birds to the small sample groups and to investigate their daytime area preferences based on their roosting pattern seems justified.

4.4. The concept of subgroup

Ž

Recent theories about the dynamics of aggression in large groups of hens Pagel and .

Dawkins, 1997 suggest that different strategies come into play at differing group sizes.

Ž .

A hen has to come quite close in order to identify another hen Dawkins, 1995 , and in

Ž .

small groups -8–10 birds this would result in dominance relationships based on individual recognition, whereas in larger groups of hens, a system depending on status signalling rather than recognition of individuals would appear. Pagel and Dawkins suggest that the limiting factor is the cost and pay off for the fights it takes to establish a peck order rather than the inability to recognize a large number of other birds individually. This theory would explain the aggression in large groups as being fights over resources with little or no individual recognition, but recognition of signals of dominance and subordination. According to the theory subgroup formation in large flocks is rather unlikely to occur as it is too costly. However, our results with flocks of about 500 birds suggest that subgroups might be formed at this flock size as we found clear indications of the existence of home ranges and there was less aggression among familiar than among unfamiliar birds. The limit where hierarchy formation based on individual recognition is no longer cost-effective has yet to be found. The contradicting results from the studies of large groups referred to in the introduction could have to do with the fact that it may be difficult to discover signs of smaller groups in a large flock in a crowded intensive system. Furthermore, lights are often quite dim under these conditions, which might cause difficulties for human observers in identifying individual

Ž .

animals as well as for the hens themselves D’Eath and Stone, 1999 .

At which group-size subgroup formation occurs is also still unknown, as is the hen’s

Ž .

preferred group-size. Lindberg and Nicol 1996a for example, found that hens had a clear preference for large groups of 70 birds over small groups of four birds. They also found that low-ranking individuals were more consistent in their choice of the larger group, suggesting that these hens could avoid persecutors more easily in large groups despite the fact that there were more birds to peck them. Lindberg and Nicol concluded that a hen’s group size preference probably is influenced by its position in the hiearchy, and also that space seems to play an important role. This may offer an explanation to the

Ž .

contradicting results from studies of smaller groups: McBride and Foenander 1962 found that groups of 80 birds did not mix, but had separate territories. Appleby and

Ž .

Jenner 1993 got much the same results when they used two groups of 40, whereas

Ž . Ž .

Widowski and Duncan 1995 and Keeling and Savenije 1995 could find no clear sign of subgroup formation as defined by local preference or preference for individual birds, within groups of 60 and 70 birds, respectively. It could be that in all these groups the birds could more or less recognize each other individually — as also suggested by

Ž .

McBride and Foenander 1962 — and that a further division into subgroups was therefore not to be expected. Maybe the group-size limit of recognition must be well

Ž .

Ž .

Furthermore, in single-sexed flocks of 400 laying hens, Craig and Guhl 1969 found a stronger tendency for individual birds to stay within a defended area as compared to

Ž .

flocks of 200 hens There were not sufficient data from flocks of 100 hens . In a flock of

Ž .

about 1200 hens, McLean et al. 1986 found that the birds did not move freely over the whole available area, but no thorough experiments were carried out to test the

hypothe-Ž .

sis of subgroup formation. In a more recent study, however, Hughes et al. 1997 concluded that in flocks of 300 birds, there was a lack of social structure, as birds seemed to react similarly to ‘‘familiar’’ and ‘‘unfamiliar’’ birds. The authors used a method rather similar to our own, with formation of sample groups. In assigning birds to ‘‘familiar’’ and ‘‘unfamiliar’’ groups, however, they caught the birds during the daytime without, as it seems, any previous monitoring and they did not record the development of agonistic behaviour continuously over time. According to our study, birds mingle more during the day than when choosing night-roost and therefore, selecting birds on the basis of night roosting site seems to give a better assessment of location constancy as well as assignment of birds to the different categories.

There is certainly a need to further examine ‘‘subgroups’’ in large flocks of laying hens. Perhaps they vary with the situation and the time of day. In large flocks in crowded environments, like those in the present study, the ‘‘subgroup’’ might perhaps be best defined as a group of acquainted birds in which the individual bird feels reassured at night or when resting at any time, while during most of the daytime the birds, independent of their ‘‘subgroup’’, use more of the total available area. Males might both strengthen the ‘‘reassurance’’ effects while resting by gathering and watch-ing over a group of females as well as durwatch-ing the day act more like ‘‘highway patrolers’’ that are spotting trouble and reacting quickly to it. In fact, in a crowded environment, as in the present study, the task of gathering and guarding is likely to be very hard. There are simply too many hens. Therefore, the direct control of aggressiveness by mere presence seems to be the most probable way the ‘‘male effect’’ works.

5. Conclusions

The results show that laying hens in large groups are rather constant in their use of space, which indicate the presence of home ranges. However, environmental features that facilitate localisation seem to be important. The results also show that hens tend to be more aggressive towards unacquainted hens than towards the hens they share the roosting site with. These findings indicate together that there existed a subgroup formation in the studied flocks. Furthermore, the high levels of aggressiveness in groups of unacquainted hens from mixed flocks when separated from the males, might be a rebound effect of the males’ reducing effect on female aggressiveness.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tina Westin, Claes-Goran Claesson and the others in the staff

¨

Edinburgh for valuable comments on an early version of the manuscript, and to Eva Andersson, University of Gothenburg, for reviewing the statistical analyses. The Swedish National Board of Agriculture and the Swedish Farmers Foundation for Agricultural Research financially supported the study.

References

Altman, D.G., 1994. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman and Hall, London.

Appleby, M.C., Hughes, B.O., Hogarth, G.S., 1989. Behaviour of laying hens in a deep litter house. British Poultry Science 30, 545–553.

Appleby, M.C., Jenner, T.D., 1993. How animals perceive group size: aggression among hens in partitioned pens. In: Proceedings of the International Congress on Applied Ethology, Berlin.

Bradshaw, R.H., 1992. Conspecific discrimination and social preference in the laying hen. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 33, 69–75.

Bolter, U., 1987. Felduntersuchungen zum Sozialverhalten von Huhnern in der Auslauf-und Volierenhaltung.¨

Eidg. Techn. Hochschule., Zurich¨ rJustus-Liebig-Univ. Giessen, Dissertation.

Ž .

Bshary, R., Lamprecht, J., 1994. Reduction of aggression among domestic hens Gallus domesticus in the

Ž .

presence of a dominant third party. Behaviour 128 3–4 , 311–324.

Collias, N.E., Collias, E.C., 1967. A field-study of the Red Junglefowl in North-Central India. The Condor 69, 360–386.

Collias, N.E., Collias, E.C., Hunsaker, D., Minning, L., 1966. Locality fixation, mobility and social organization within an unconfined population of red jungle fowl. Animal Behaviour 14, 550–559. Craig, J.V., Bhagwat, A.L., 1974. Agonistic and mating behaviour of adult chickens modified by social and

physical environments. Applied Animal Ethology 1, 57–65.

Craig, J.V., Guhl, A.M., 1969. Territorial behaviour and social interactions of pullets kept in large flocks. Poultry Science 48, 1622–1628.

Dawkins, M.S., 1995. How do hens view other hens? The use of lateral and binocular visual fields in social recognition. Behaviour 132, 591–606.

Dawkins, M.S., 1996. Distance and social recognition in hens: Implications for the use of photographs as social stimuli. Behaviour 133, 663–680.

D’Eath, R.B., Stone, R.J., 1999. Chickens use visual cues in social discrimination: an experiment with coloured lighting. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 62, 233–242.

Gibson, S.W., Dun, P., Hughes, B.O.,1986. The performance and behaviour of laying fowls in a covered straw-yard system 1983–1986. Scottish. Agr. Colleges Research and Development, Note. 35.

Grigor, P.N., Hughes, B.O., Appleby, M.C., 1995. Social inhibition of movement in domestic hens. Animal Behaviour 49, 1381–1388.

Guhl, A.M., 1953. Social behaviour of the domestic fowl. Technical Bulletin of the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station 73, 1–48.

Hughes, B.O., 1977. Selection of group size by individual laying hens. British Poultry Science 18, 9–18. Hughes, B.O., Carmichael, N.L., Walker, A.W., Grigor, P.N., 1997. Low incidence of aggression in large

flocks of laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviours Science 54, 215–234.

Hughes, B.O., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Morley Jones, R., 1974. Spatial organization in flocks of domestic fowls. Animal Behaviour 22, 438–445.

Keeling, L.J., Savenije, B., 1995. Flocks of commercial laying hens: organised groups or collections of individuals. In: Proc. 29th International Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology, Exeter, U.K. p. 187.

Lindberg, A.C., Nicol, C.J., 1996a. Space and density effects on group size prefences in laying hens. British Poultry Science 37, 709–721.

Lindberg, A.C., Nicol, C.J., 1996b. Effects of social and environmental familiarity on group preferences and spacing behaviour in laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 49, 109–123.

McBride, G., Foenander, F., 1962. Territorial behaviour in flocks of domestic fowls. Nature 194, 102. McBride, G., Parer, J., Foenander, F., 1969. The social organization and behaviour of the feral domestic fowl.

Animal Behaviour Monograph 2, 127–181.

McLean, K.A., Baxter, M.R., Michie, W., 1986. A comparison of the welfare of laying hens in battery cages

Ž .

and in a perchery. Research and Development in Agriculture 3 2 , 93–98.

Oden, K., Vestergaard, K.S., Algers, B.O., 1999. Agonistic behaviour and feather pecking in single-sexed and´

mixed flocks of laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 62, 219–231.

Pagel, M., Dawkins, M.S., 1997. Peck orders and group size in laying hens: ‘‘future contracts’’ for non-aggression. Behavioural Processes 40, 13–25.

Vestergaard, K.S., 1994. Dustbathing and its relation to feather pecking in the foul: motivational and developmental aspects. Dissertation. The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen. Widowski, T.M., Duncan, I.J.H., 1995. Do domestic fowl form groups when resources are unlimited? In:

Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of the ISAE, 3–6 August 1994, in Foulum, Denmark. p. 140.

Zayan, R., 1987a. Recognition between individuals indicated by aggression and dominance in pairs of

Ž .

domestic fowl. In: Zayan, R., Duncan, I.J.H. Eds. , Cognitive Aspects of Social Behaviour in the Domestic Fowl. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 321–438.

Zayan, R., 1987b. An analysis of dominance and subordination experiences in sequences of paired encounters

Ž .