Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:59

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Role of Multi-Institutional Partnerships in

Supply Chain Management Course Design and

Improvement

Suzanna Long , J. Chris Moos & Anne Bartel Radic

To cite this article: Suzanna Long , J. Chris Moos & Anne Bartel Radic (2012) The Role of Multi-Institutional Partnerships in Supply Chain Management Course Design and Improvement, Journal of Education for Business, 87:3, 129-135, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.582190

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.582190

Published online: 01 Feb 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 139

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.582190

The Role of Multi-Institutional Partnerships

in Supply Chain Management Course Design

and Improvement

Suzanna Long

Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, Missouri, USA

J. Chris Moos

Missouri Southern State University, Joplin, Missouri, USA

Anne Bartel Radic

Universit´e de Savoie, Chambery, France

The authors examined the skills achieved through a multicultural, virtual student project envi-ronment among 3 supply chain management courses. The partnership included 2 universities in the United States and 1 in France and created virtual teams of students across university lines and is presented as a case study. The case includes detailed descriptions of collaborative partners and identification of organizational readiness factors, curriculum design elements, a discussion of multi-institutional project design, and concludes with a framework for successful multi-institutional collaboration.

Keywords: case study, global learning, multicultural partnership, supply chain management curriculum design, virtual student teaming

Global strategies and skill sets are essential to meet the chal-lenges of modern business environments. Supply chain man-agement business professionals must be prepared to excel in a variety of social, political, and cultural settings. This preparation must begin in the classroom as an essential com-ponent of supply chain management programs. This is easier said than done as there is, as yet, no proven methodology for integrating global concepts into academic coursework.

In this case study we develop a supply chain management curriculum that emphasizes the role of multicultural, student-centered projects in preparing students for the global workforce. A framework for using multi-institutional partnerships is developed to provide students with real-world scenarios that explore collaboration across organizational cultures, time zones, and practice. This fosters experience-based learning and examines the value-added skills achieved

Correspondence should be addressed to Suzanna Long, Missouri Uni-versity of Science and Technology, Department of Engineering Management and Systems Engineering, 600 W. 14th Street, 215 EMGT Building, Rolla, MO 65401, USA. E-mail: longsuz@mst.edu

through the addition of a multicultural, virtual student project environment to three supply chain–logistics man-agement courses. The partnership includes two universities in the United States and one in France and creates virtual, interdisciplinary student teams across university lines and international borders. Lessons learned are used to create a framework for use by other universities interested in using this approach to global learning.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature presented as part of this study is divided into three main areas: the need for global content, the importance of communications skills, and administrative complexity in adding global content.

Global Content

Traditional supply chain courses provide students with lim-ited introductions to global processes and concepts. Only 2.9% of the students sampled in the 1980s and 1990s felt

130 S. LONG ET AL.

that they had sufficient knowledge of global marketing to compete in complex international distribution systems (Bess & Collison, 1987; Turley & Shannon, 1999). In 2003, Kedia and Daniel reported that among 111 U.S. Fortune 500 compa-nies, 70% reported insufficient globally competent personnel to fully exploit international business opportunities. These companies further reported difficulty finding U.S. nationals with international knowledge, expertise, or language skills (Kedia & Daniel). Recently, U.S. colleges and universities have begun to make attempts to address this issue, in part, due to pressure from national accreditation bodies that have embraced the importance of globalization (Hoffman, 2005). Globalization of students and programs should be infused through a united front from university governing bodies to the classroom (Jefferson, 2001) and include relevant instruc-tion in standard business terms and security issues (Pagliari, 2005). International trips, when properly structured as mobile classrooms, are excellent means for giving students a more global perspective (Loveland, Abraham, & Bunn, 1987). In-ternational trips are even more effective when preceded by a curriculum that includes cultural biases and idioms that demonstrate the relevance of culture as an influence on the business environment (Tuleja, 2008).

Participative case studies are useful tools for student learning. Rather than working only with prewritten cases, students should research and write cases for analysis, especially at the MBA level (Forman, 2006). but also for undergraduate students who, although they may not be ready to write a case, can research and discuss present topics as part of a facilitated discussion.

Communications Skills

Students must receive adequate leadership training that builds their communication and interpersonal skills to be successful in the 21st century workplace (Hicks, Westbrook, & Utley, 1999). Global communication requires elements of strategic partnering to truly be effective (Lohmann, 2008; Long & Spurlock, 2008; Sheppard, Pellegrino, & Olds, 2008). Inter-cultural competence must include the skills to analyze, inter-pret, and relate information effectively as well as the ability to listen and observe. Cognitive skills, including comparative thinking skills and cognitive flexibility, are also essential for effective communication (Deardorff, 2006; Johnson, Lenar-towicz, & Apud, 2006). Curriculum redesign is necessary to ensure such important skills as these are demonstrated (Kelley & Bridges, 2005; Pate-Cornell, 2001).

Preparation for global learning must include study ele-ments on how cultural mores affects the local business en-vironment (Clarke & Flaherty, 2003; Johnson et al., 2006; Loveland et al., 1987). Units detailing cultural diversity and cross-cultural analysis provide context for understanding not only the fundamentals of economic policies, but also for demonstrating the need for market differentiation strategies in global markets (Mitry, 2008). Student goals and

goal-setting abilities can be strong predictors of success in the development of cross-cultural skills (Kitsantas, 2004). Re-ducing ethnocentricity in students can be accomplished by redesigning existing curriculum to include global compo-nents (Walton & Basciano, 2006). Programs that consider the role those goals play on student skills development are the most effective in providing global frameworks.

Supply chain courses should include opportunities to practice communication skills as well as discussions of present global issues (Tryggvason & Apelian, 2006). This must include skills development as part of virtual teams. Virtual teams are defined as groups of geographically and organizationally dispersed knowledge workers brought to-gether through information and communication technologies (i.e., e-mail, videoconferencing, or other computer-mediated communication systems) in response to specific needs or to complete unique projects (DeSanctis & Poole, 1997; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1998; Lipnack & Stamps, 1997, 2000).

Administrative Complexity

Although few programs are truly global in terms of their audience and scope, all can import an awareness of glob-alization to their students. Institutional resources can have a profound influence on the scope and nature of globaliza-tion curricula implementaglobaliza-tion. Large, top-tier universities are twice as likely as smaller institutions to approach global-ization through the creation of standalone international pro-grams due to the level of resources available and commitment by governing bodies (Rudell, 2002). Smaller programs can gain benefit from the use of global case studies and other enhancements (Lorange, 2003).

Regardless of size, it is important to engage faculty and administration to prevent resistance to traditional patterns of academic autonomy (Crosling, Edwards, & Schroder, 2008). An important first step is awareness that what works for one country may not guarantee success in another.

PROGRAM OVERVIEWS AND COLLABORATIVE DESCRIPTIONS

An international partnership of business and engineering sup-ply chain–logistics faculty was developed to link their ex-isting supply chain courses through common international projects. This collaborative grew from an existing exchange program between two of the partner universities, Missouri Southern State University (US1) and L’Institut de Manage-ment de Universit´e de Savoie (French1). A third univer-sity, Missouri University of Science and Technology (US2) joined the collaborative in the second year. The partners drew on combined strengths in supply chain–logistics education while supplementing educational pedagogy through unique program approaches. The Department of International Busi-ness at US1 explores supply chain management from a U.S.

business school perspective. The Department of Engineer-ing Management and Systems EngineerEngineer-ing at US2 brEngineer-ings engineering pedagogy to the partnership. French1 brings the French business school perspective to the partnership. French School and US2 offer graduate degrees.

At US1 students study the concept of supply chain positioning. Students are actively encouraged to select upper division electives that provide content in foreign language, culture, or other business areas to facilitate a greater appreciation of the modern business environment. At the US2 students explore concepts of technological innovation, supply chain optimization, and strategic partnering. The courses are open to upper division undergraduate and grad-uate students. The students participating in the international projects from French1 are second year master’s degree students in international logistics. The student cohorts are employees in a company as part of their studies. This continuous change between the company and the university helps students to put theory into practice.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS DESIGN

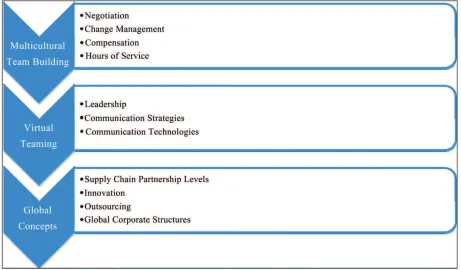

The collaborative projects approach was designed as the equivalent of a multi-institutional capstone course. Multicul-tural team building and virtual teaming were the key factors used to develop teaching modules on communications and global concepts. These modules provided the basic framework for the collaborative projects and were integrated

throughout the course to provide needed context for the project scenarios. Outlines of the learning modules are presented in Figure 1.

Each research team was designed to consist of students from all three cooperating institutions. Students were re-quired to collaborate on course projects utilizing various methods of communication and contact consistent with the creation of an international classroom (Leask, 2004). This approach provided the basis for an experience with global supply chain issues, and real-world intercultural communi-cations, time zones, time management, and virtual teaming. Although project descriptions were provided, deliberate am-biguity was created in terms of the establishment of mile-stones and project objectives to more naturally simulate vir-tual teaming in global organizations.

Projects compared supply chain management organi-zations and networks in France with the United States. This allowed each team to have some familiarity with part of the project, but also required that each team member study and learn from team members about an-other culture. Team project presentations were made in the United States and France. Examples of projects com-pleted as part of the collaborative partnership included the following:

1. Toyota systems: a comparison and contrast of Toyota by region (e.g., United States vs. France) that included a cross-cultural analysis of manufacturing methods

FIGURE 1 Learning modules with relevant content. (Color figure available online).

132 S. LONG ET AL.

TABLE 1

Evaluation Questions by Topical Area

Question Survey questions Topical area(s)

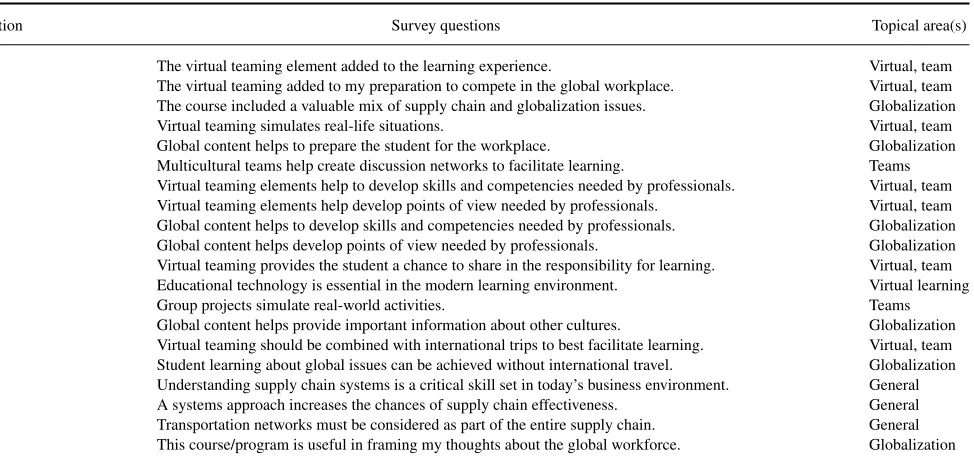

1 The virtual teaming element added to the learning experience. Virtual, team 2 The virtual teaming added to my preparation to compete in the global workplace. Virtual, team 3 The course included a valuable mix of supply chain and globalization issues. Globalization 4 Virtual teaming simulates real-life situations. Virtual, team 5 Global content helps to prepare the student for the workplace. Globalization 6 Multicultural teams help create discussion networks to facilitate learning. Teams 7 Virtual teaming elements help to develop skills and competencies needed by professionals. Virtual, team 8 Virtual teaming elements help develop points of view needed by professionals. Virtual, team 9 Global content helps to develop skills and competencies needed by professionals. Globalization 10 Global content helps develop points of view needed by professionals. Globalization 11 Virtual teaming provides the student a chance to share in the responsibility for learning. Virtual, team 12 Educational technology is essential in the modern learning environment. Virtual learning 13 Group projects simulate real-world activities. Teams 14 Global content helps provide important information about other cultures. Globalization 15 Virtual teaming should be combined with international trips to best facilitate learning. Virtual, team 16 Student learning about global issues can be achieved without international travel. Globalization 17 Understanding supply chain systems is a critical skill set in today’s business environment. General 18 A systems approach increases the chances of supply chain effectiveness. General 19 Transportation networks must be considered as part of the entire supply chain. General 20 This course/program is useful in framing my thoughts about the global workforce. Globalization

2. Road transportation: an exploration of how road sys-tems and networks impact logistics planning; the project considered congestion reduction

3. Distribution in city centers: a look at cross-cultural differences in the marketplace (United States vs. France) and how that impacts the supply chain in terms of business channels and distribution networks (e.g., warehousing)

4. Alternatives to fuel in transport: a look at issues of sustainability and energy management policies. How do alternative fuels impact the value chain of the supply chain? What alternative infrastructures are needed or in place (United States vs. France)?

The structure of the class projects was specifically de-signed to include goal-setting behavior for the projects and intercultural relations. Research has shown that goal-setting behavior significantly enhances a participant’s performance (Bartel-Radic, 2006; Schunk, 2000) and plays an instru-mental role in improving student self-efficacy and intrinsic interest in the task. In addition the course design allowed for the creation of specific tasks, roles, and learning goals. Specifically, each student was identified as either a project manager or researcher; tasks were divided up into smaller focused tasks with frequent reporting requirements, and specific questions directed toward the intercultural relations, communications, and learning were included. This specific task, role, and learning goal focus has been identified as a necessary component for a successful intercultural learning environment (Gabb, 2006).

DISCUSSION

Detailed surveys were completed to assess student learning and attitudes regarding virtual teaming in cross-cultural situations in the second year of the partnership. Student learning and satisfaction were further evaluated based on experiences with virtual, collaborative teaming among the three universities. Key factors examined included the following: a) the virtual teaming added to the learning experience, b) the multicultural teaming effort added to student preparation to compete in the global workplace, and c) the valuable level of global content included in the course. Student perceptions of the global competencies needed for a global workforce are useful in determining mechanisms for facilitating learning and correcting common misconceptions held by students. We have used student perceptions of these important facets of global business to best compile ancillary readings and other materials to supply context and cement understanding of the complexity of the global workplace. A summary of questions by topical area is presented in Table 1. Results were discussed as part of a larger lessons-learned meeting at the conclusion of the semester.

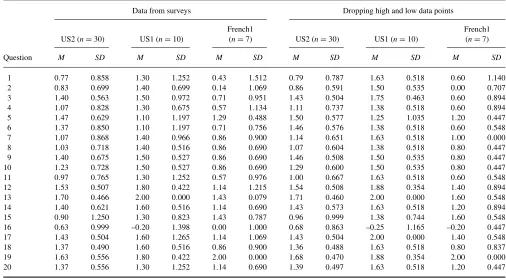

Evaluation data were collected at the end of the semester through an online survey mechanism. Students were asked to identify their university, but not asked to provide any addi-tional demographic information to help preserve anonymity. A standard 5-point Likert-type scale was used to measure level of agreement; however, we chose to shift the usual 1–5 scale to a scale of –2 to 2. This was done purely for aesthetics. As such, responses ranged from –2 (strongly disagree) to 2 (strongly agree).

TABLE 2

Evaluation Data Means and Standard Deviations

Data from surveys Dropping high and low data points

US2 (n=30) US1 (n=10)

Table 2 presents average values and standard deviations for all evaluation data. The left half of Table 2 shows averages and standard deviations for all data from the three partner schools. The right half of the table presents these results with high and low data points dropped (thereby removing the affect of a single outlier). There is no significant difference between the two halves.

Although the relatively small sample size did not allow any test for statistical significance, some trends were im-plied. Results were positive regarding the approach with satisfaction levels for all but one question in the slightly or strongly agree categories. Levels of satisfaction were higher for the senior undergraduate business students at US1 than at the other partner schools. French1 graduate business stu-dents showed a dropoff in satisfaction levels when questioned about the value of virtual elements as learning tools. The re-sponses were still positive, but at a much lower level. The senior undergraduate and graduate engineering students at US2 were less convinced of the value of global content or teams as a simulation of real-world experience. However, US2 students were strongly accepting of the value of supply chain content as vital for preparation in engineering.

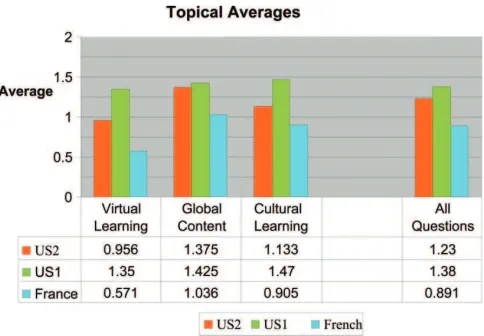

Figure 2 presents an evaluation of progress toward top-ical goals. U.S. student results were similar and combined for general comparison against the student results from the French school. Our results show a 45% higher level of sat-isfaction with virtual learning for U.S. students when com-pared with the French students. Similarly, a 25% difference

was seen in U.S. student satisfaction levels with global con-tent and cultural learning when compared with the French students. It is also interesting to look at trends from individ-ual questions. Students at US1 were part of an international business degree program that frequently offers coursework online. As a result of increased experience with online learn-ing, the US1 students had a higher appreciation for the three learning aims of this collaborative. Students at US2 were en-gineering majors in which the overwhelming majority of courses are in a traditional face-to-face environment. An overview of student characteristics common to engineering students frequently includes high quantitative skill levels, but less developed social skills, such as those that facilitate ef-fective team building (Hicks et al., 1999). US2 students were less comfortable with a team approach to learning, especially if that approach involved virtual learning.

French1 students were clearly the most uncomfortable with the virtual learning elements and saw less value in the team approach. Similar to the students at US2, French School students had not been previously exposed to virtual learn-ing. Postclass interviews with the French School students revealed that their dissatisfaction with the teaming element was rooted in cultural misunderstanding, despite efforts to introduce a module aimed at multicultural team building. Students experienced early communications issues due to e-mail system failures at the French partner university. Cul-tural misunderstandings grew in intensity once communica-tion was restored based on stereotypes, language difficulties,

134 S. LONG ET AL.

and approaches to resolving ambiguity. Moreover, graduate students at French School resented loss of authority to un-dergraduate students.

The differences in course timelines and schedules created complexities as well. French students enroll for the equivalent of two U.S. semesters and are not on campus full-time. The shortened window of collaboration required flexibility on the part of all student team members and created a real-world opportunity to experience asynchronous communication is-sues, along with cross-organizational planning. Moreover, the multiple bosses reality of the virtual teaming presented challenges for students and collaborating professors to main-tain consistent messages and project outcomes.

Planning efforts should develop learning goals and outcomes prior to the formation of student groups. Accept-able cases, study formats, and other project team elements should be developed that incorporate the learning styles and program strengths of each partner school. Each course should contribute a unique facet to the project structure and clear measurement systems should be in place. Common grading rubrics are useful means of communicating goals linked to teaming, subject matter expertise, and critical thinking elements.

If possible, group project reports should be evaluated as a faculty team rather than scored individually at each school. This adds a layer of complexity, but does convey the impor-tance of the projects to the students. Joint controls facilitate teaming efforts that focus on performance and the sustainable elements of relationship building rather than on individual results that may or may not be shared.

Partnerships of this type will be dependent on virtual com-munication and subject to time-zone and cultural differences. It is important to schedule regular conversations regarding the student teaming efforts. These conversations will be most productive if a mix of e-mail and voice communication is scheduled.

FIGURE 2 Student progress toward learning modules topical goals. (Color figure available online).

CONCLUSIONS

Our multi-institutional partnership experiences suggest that students gain global perspectives through the introduction of integrated project teams to supply chain curriculum. Overall, results indicate that progress was made toward mastery of our topical goals of virtual teaming, global content, and cultural learning. However, some differences did emerge. Our results (Figure 2) show a 45% higher level of satisfaction with virtual learning for U.S. students when compared with the French students. Similarly, a 25% difference was seen in U.S. student satisfaction levels with global content and cultural learning when compared with the French students.

It is also interesting to look at trends from individual ques-tions. Despite the increased use of technology by students for social networking, many lack experience in its application to the classroom; the same can be said of the faculty. Students who had prior experience with the online learning environ-ment had an easier time with virtual collaboration. Student attitudes show a clear bias for their own customs and learning traditions. The differences in course timelines and schedules create unresolved complexities. The short window of col-laboration requires flexibility on the part of all student team members. The multiple bosses reality continued to present challenges for students and collaborating professors through-out the project.

Despite the challenges, we feel that this approach provides students the opportunity to step outside of their traditional comfort zones and work with students of very different cul-tural and academic backgrounds. Furthermore, the students mentioned in exit interviews that they found value in the abil-ity to work with their counterparts from other universities.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Although globalization has been incorporated into the cur-riculum, the effectiveness of methods has not yet been fully analyzed. Difficulties with adaptability at the student and fac-ulty levels suggest the need for further analysis of root causes. Incorporating change management theory and best practices may prove useful. The full implications of what this means in terms of longitudinal success beyond the classroom ex-perience has yet to be determined. In future researchers we will examine the extent to which attitudes are changed and a more global perspective is achieved by tracking graduates of the program into the workforce and conduct periodic surveys to determine whether enthusiasm and perceived value for the instructional approach has waned over time.

REFERENCES

Bartel-Radic, A. (2006). Intercultural learning in global teams.Management International Review,46, 647–677.

Bess, H. D., & Collison, F. (1987). Transportation and logistics curricula: Still too domestic?Transportation Journal,26(3), 48–58.

Clarke, I. III, & Flaherty, T. B. (2003). Challenges and solutions for market-ing educators teachmarket-ing in newly emergmarket-ing markets.Journal of Marketing Education,25, 118–128.

Crosling, G., Edwards, R., & Schroder, B. (2008). Internationalizing the curriculum: The Implementation experience in a faculty of business and economics.Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,30, 107–121.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural com-petence as a student outcome of internationalization.Journal of Studies in International Education,10, 241–266.

DeSanctis, G., & Poole, M S. (1997). Transitions in teamwork in new organizational forms.Advances in Group Processes,14, 157–176. Forman, H. (2006). Participative case studies: Integrating case writing and

a traditional case study approach in a marketing context.Journal of Mar-keting Education,28, 106–114.

Gabb, D. (2006). Transcultural dynamics in the classroom.Journal of Studies in International Education,10, 357–368.

Hicks, P. C., Westbrook, J. D., & Utley, D. R. (1999). What are we teach-ing our engineerteach-ing managers?Engineering Management Journal,11(1), 29–34.

Hoffman, W. (2005, January 10). Logistics’ evolving curriculum.Traffic World, 19–21.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1998). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Journal of Computer Mediated Communica-tion, 3(4). Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ jcmc.1998.3.issue-4/issuetoc. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1998.tb00080.x Jefferson, R. W. (2001). Preparing for globalization—do we need structural

change for our academic programs?Journal of Education for Business,

76, 160–166.

Johnson, J. P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural compe-tence in international business: Toward a definition and a model.Journal of International Business Studies,37, 525–543

Kedia, B. L., & Daniel, S. (2003, January).U.S. business needs for employees with international expertise. Paper presented at the Needs for Global Challenges Conference Proceedings, Duke University, Durham, NC. Kelley, C. A., & Bridges, C. (2005). Introducing professional and career

development skills in the marketing curriculum.Journal of Marketing Education,27, 212–219.

Kitsantas, A. (2004). Studying abroad: The role of college students’ goals on the development of cross-cultural skills and global understanding.College Student Journal,38, 441–452.

Leask, B. (2004). Internationalisation outcomes for all students using in-formation and communication technologies (ICTs).Journal of Studies in International Education,8, 336–351.

Lipnack, J., & Stamps, J. (1997).Virtual teams: Reaching across space, time, and organizations with technology. New York, NY: Wiley. Lipnack, J., & Stamps, J. (2000).Virtual teams: People working across

boundaries with technology(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Lohmann, J. (2008). A rising global discipline.Journal of Engineering Education,97, 227–230.

Long, S., & Spurlock, D. (2008). Motivation and stakeholder acceptance in technology-driven change management: Implications for the engineering manager.Engineering Management Journal,20(2), 30–36.

Lorange, P. (2003). Global responsibility—Business education and busi-ness schools—Roles in promoting a global perspective.Corporate Gov-ernance,3, 126–135.

Loveland, T. L., Abraham, Y. T., & Bunn, R. G. (1987). International busi-ness study tours: Practices and trends.Journal of Education for Business,

62, 253–256.

Mitry, D. (2008). Using cultural diversity in teaching economics: Global business implications.Journal of Education for Business,84, 84–89. Pagliari, L. (2005). Developing a global logistics course.Journal of

Com-merce,6, 14–36.

Pate-Cornell, M. E. (2001). Management of post-industrial systems: Aca-demic challenges and the Stanford experience.International Journal of Technology Policy and Management,1, 151–159.

Rudell, M. F. (2002). Internationalizing the business program—A perspec-tive of a small school.Journal of Education for Business,78, 103– 110.

Sheppard, S., Pellegrino, J., & Olds, B. (2008). On becoming a 21st century engineer.Journal of Engineering Education,97, 231–235.

Schunk, D. H. (2000).Learning theories: An educational perspective(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Tryggvason, G., & Apelian, D. (2006). Re-engineering engineering edu-cation for the challenges of the 21st century.Journal of Management,

58(10), 14–17.

Tuleja, E. A. (2008). Aspects of intercultural awareness through an MBA study abroad program: Going backstage.Business Communication Quar-terly,71, 314–337.

Turley, L.W., & Shannon, J. R. (1999). The international marketing curricu-lum: Views from students.Journal of Marketing Education,21, 175–181. Walton, J., & Basciano, P. (2006). The internationalization of American business education: Are U.S. business students less ethnocentric?The Business Review,5, 282–286.