The Erosion of the Glass–Steagall Act:

Winners and Losers in the Banking Industry

Ken B. Cyree

This paper studies stock price reaction to increased investment banking powers for commercial banks using Seemingly Unrelated Regressions. Market participants react favorably to the announcement of increased Section 20 powers to the Glass-Steagall Act both with and without a risk-shift variable. When the sample is split, abnormal returns are significantly higher for Money Center Banks, banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries, and Large Regional commercial banks as compared to Small Regional banks. Cross sectional analysis suggests that banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries have higher abnormal returns and Small Regional banks have lower abnormal returns than the average

bank in the sample. © 2000 Elsevier Science Inc.

Keywords: Glass-Steagall Act; Section 20 subsidiaries

I. Introduction

This paper studies the effects of increased investment banking powers in the commercial banking industry. Section 20 of the Glass–Steagall Act, as amended on December 20, 1996, allows commercial bank affiliates to underwrite up to 25% of revenue in previously ineligible securities of corporate equity or debt. Commercial banks are tested for overall and differential reaction across groups of banks to increased investment banking powers and share price reaction is compared in cross sectional models.

Bhargava and Fraser (1998) study the proposed increase in the Section 20 loophole, along with other prior Section 20 events, and find that the 1996 action had few wealth effects. However, Bhargava and Fraser only studied the market reaction to the initial proposal by the Federal Reserve to increase the loophole to 25% of subsidiary revenue. One of the contributions of this paper is that the interim events and subsequent adoption of the increase in the Section 20 revenue limits is explicitly studied along with the reaction of competing Small Regional banks.

Department of Economics and Finance, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS

Address correspondence to: Dr. Ken B. Cyree, Department of Economics and Finance, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406-5076, USA.

Results show that share prices react favorably to the adoption of increased Section 20 powers to the Glass–Steagall Act in models both with and without risk-shift variables. Abnormal returns are significantly higher for Money Center Banks, banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries, and Large Regional commercial banks as compared to Small Regional banks. Cross sectional analysis shows that banks with prior Section 20 subsid-iaries have higher abnormal returns and Small Regional banks have lower abnormal returns than the average bank in the sample.

II. Background on the Glass–Steagall Act

The Glass–Steagall Act was passed in 1933 to prohibit National and Federal Reserve member banks and bank holding companies (BHCs) from underwriting corporate equity and debt.1The Act was passed due to perceived conflicts of interest between banking and underwriting and actions related to the findings of the Pecora Committee.2Many advo-cates of the Glass–Steagall Act claim the potential conflicts of interest between commer-cial and investment banking are too severe and these enterprises should remain separate. Conflicts of interest arise if banks underwrite equity and bank customers use the proceeds to repay bank loans. Conflicts can also arise if banks make loans to customers who purchase other bank underwritten securities, or additionally if banks use proprietary customer lending information to direct underwriting. In addition, many claim the presence of deposit insurance negates the incentive for monitoring the investment activities in a combined entity.

Commercial banks can underwrite eligible securities, such as Treasury securities, general obligation municipal securities, and privately placed equities. Beginning in 1986, the Federal Reserve also allowed BHCs to underwrite previously ineligible debt and equity through related bank affiliates or subsidiaries under Section 20 of the Glass– Steagall Act. BHC subsidiaries could have up to 10% of total subsidiary revenues in “ineligible” corporate debt and equity. On December 20, 1996, the Federal Reserve modified Section 20 of Glass–Steagall, increasing the limit from 10% of subsidiary revenue to 25% and making the demise of Glass–Steagall more likely.

Banks desire the ability to underwrite corporate debt and equity for many reasons. Securities underwriting can offer corporate customers “one-stop shopping,” and allow for informational synergies between the commercial and investment banking subsidiaries. Because commercial customers are issuing commercial paper and foregoing short-term loans, the investment bank subsidiary could strengthen customer loyalty and secure more traditional bank activity. Mester (1997) reports that the average return on equity for investment banks was about 17.5% and 11% for commercial banks from 1990 to 1993. With narrowing commercial bank spreads and increased nonbank competition, higher performance is very lucrative for commercial bank stakeholders. If underwriting activities lower bank risk through diversification, the industry would experience a risk reduction and the deposit insurance fund would be safer. Other benefits include greater presence in global markets, technology and innovation among affiliates, and others.

The majority of research of the potential repeal of Glass–Steagall has focused on the conflict of interest inherent in commercial banking and investment banking or

perfor-1The term bank is used to denote bank holding company throughout the paper with all variables aggregated

at the holding company level where appropriate.

mance of banking firms around increased investment banking activity. This paper studies whether the commercial banking industry benefits from increased investment banking powers or not, and which commercial banks benefit from increased investment banking powers and which do not.

III. Literature

Most prior research has focused on whether the Glass–Steagall Act is necessary due to conflicts of interest, or performance and diversification issues related to Glass–Steagall. In this section, I discuss the conflicts of interest literature in three different areas: the theoretical papers that formalize the issue, papers examining long term performance of commercial bank versus investment bank underwritten issues, and ex-ante pricing of commercial bank versus investment bank underwritten issues. I also review the literature that studies performance of increased banking powers on commercial bank stock perfor-mance.

Theoretical Conflicts of Interest Literature

Several theoretical papers formalize the conflicts of interest inherent in commercial banks underwriting securities. Saunders (1985) identifies nine potential conflicts of interest such as promotional role versus advisor, economic tie-ins, director interlocks, and using security proceeds to repay bank loans. In general, Saunders argues that maximization of long-run profits implies preservation of reputation and, therefore, avoidance of exploita-tion of conflicts of interest by commercial banks engaged in investment banking activities. He suggests outside mechanisms such as the market for corporate control, competitive market for financial services, default ratings of ratings agencies, and penalty power of regulators provide a check on potentials for abuse.

Benston (1994) similarly reviews the potential for conflicts of interest by reviewing Germany’s example of universal banking. He discusses financial stability, economic development, political power, consumer choice, and conflicts of interest. Benston finds that universal banking has potential for considerable benefits and poses few problems for the economy. Benston suggests that Glass–Steagall should be repealed.

Kanatas and Qi (1998) present a theoretical model of firms seeking project funding with both combined and separate commercial and investment banking. They find that economies of scope could enable combined entities to capture the borrowers’ underwriting business, which can reduce the firm’s investment. When modeled with firm’s incentive to lower costly project development in anticipation of underwriting by lenders, the result is that combination of commercial and investment banking poses a social welfare cost. However, if the combined commercial and investment bank has incentive for reputation building, the social costs of combination are mitigated without the need for regulation.

Puri’s model also suggests that banks and investment banks can coexist in the market and explains the rationale for the coexistence in the U.K. and France.

Overall, the theoretical literature suggests that conflicts of interest and other social costs associated with combining commercial and investment banking can be mitigated through outside forces or reputation effects. Therefore, theory suggests that combining these activities is not likely to harm the industry or create a social cost as opponents suggest. One exception is Rajan (1998) who shows that unrestricted competition does not necessarily lead to efficient institutions if the markets in which institutions compete are not naturally competitive. Rajan suggests that for an integrated producer, ex-post rents are possible if an information advantage exists. Because commercial banks are intensive information gatherers, Rajan suggests the ex-post rents could be greater than the ineffi-ciencies due to integration.

Commercial versus Investment Bank Underwritten Security Performance Literature

In general, long term performance studies of commercial versus investment bank under-written securities indicates no difference between the two underwriting groups, or that bank underwritten securities perform better. For example, Kroszner and Rajan (1994) find the ex-post default performance of Section 20 affiliate underwritten securities is better than comparable investment bank underwritten issues. The results were most evident for lower grade securities and more “information intensive” issues.

Ang and Richardson (1994) find no evidence that bonds underwritten by commercial banks underperformed those underwritten by investment banks. Bank affiliate issues had lower default rates, higher ex-post prices, and no difference in yield/price relationships when compared to investment bank issues. Ang and Richardson, as well as Puri (1994) find the two commercial banks that were the focus of the Pecora Committee had practically all categories of bonds fare worse than similar issues by other commercial bank affiliates. National City Corp. and Chase Securities, the two banks in question, had higher default rates, but the market was not fooled by these underwriters because their securities also had higher initial yields.

For the period from 1927 to 1929 before Glass–Steagall, Puri (1994) tests whether or not yields differ between securities underwritten by investment houses versus those underwritten by commercial banks. Puri finds that commercial bank underwritten issues have lower yields ex-ante (higher prices) and, therefore, the certification effect of bank inside information outweighs the conflicts of interest effect for corporate securities. Puri also finds that the certification effect is higher for bonds versus preferred stock, new versus seasoned issues, and for non-investment grade versus investment grade securities. These results imply that corporate customers would benefit from the repeal of the Glass–Steagall Act.

In related research conflicts of interest research, Hamao, Packer, and Ritter (1998) find that Japanese firms with venture capital backing from securities company subsidiaries perform significantly worse over a 3-year time horizon than other IPOs. Results suggest that conflicts of interest influence the pricing and long-run performance of initial public offerings in Japan. Gompers and Lerner (1999) review underwriting of IPOs by invest-ment banks that hold equity through a venture capital subsidiary. Gompers and Lerner find that affiliated issues perform as well or better than those where the investment bank did not hold an equity position. They suggest their findings offer no support for prohibitions on universal banking instituted by Glass–Steagall.

Ex-ante Pricing Literature

Ex-ante pricing of commercial versus investment bank underwritten securities is well studied. Ang and Richardson (1994) and Puri (1996) find that securities underwritten by commercial banks before Glass–Steagall had higher ex-ante prices than investment bank issues, and this effect is stronger for junior and information intensive issues. Gande, Puri, Saunders, and Walter (1997) also find bank underwritten issues higher priced than investment bank issues, particularly for small and non-investment grade securities. Gande, Puri, and Saunders (1999) find a reduction in underwriter spreads among lower rated and small size debt issues from 1985 to 1996 after the weakening of Glass–Steagall. Bank entry into the underwriting market reduced spreads initially, but did not persist through time as investment banks apparently matched spreads on an immediate basis.

Hamao and Hoshi (1997) study bond underwriting by bank subsidiary securities firms in Japan and find neither certification effects or conflicts of interest dominates the bank underwriting of corporate bonds. Japanese bank subsidiaries do, however, bring smaller issues to the market than do existing securities firms suggesting increased access to capital markets for smaller firms.

Bank Risk and Performance around increased Investment Banking Activity

Several studies review performance or changes in risk of the banking firm around increased underwriting powers. Kwast (1989) reviews the potential for diversification gains by banks expanding into underwriting securities. The return on assets and standard deviation for securities activities are higher than the return on assets and standard deviation for commercial banks. Boyd, Graham, and Hewitt (1993) use accounting values and market data to simulate mergers between commercial banks and financial service firms. The simulations using accounting data suggest that BHC’s that merge with firms in any of the four non-banking industries (securities, real-estate, real-estate development, and insurance agent/broker) increase the risk of failure at virtually any portfolio weight.

Saunders and Smirlock (1987) study performance around the initial increase in invest-ment banking powers for commercial banks. They found that banks expanding into discount brokerage insignificantly affected bank share price reaction and risk. However, Saunders and Smirlock find that securities firms experience a significant decline in market value.

investment banks were negative and insignificant. They also find that risk did not decline significantly for any of the groups around the initial increase in underwriting power for commercial banks.

Bhargava and Fraser (1998) use a multivariate regression model to study prior effects of four Federal Reserve Board decisions that allowed commercial banks to participate in investment banking through Section 20 subsidiaries. When the less expansive powers to underwrite mortgage securities and municipal revenue bonds were initially proposed in April 1987, banks that participated experienced positive and significant abnormal returns. When these powers were expanded in January 1989 to include corporate debt and equity, as well as the subsequent decision to double the amount allowed in September 1989, banks experienced negative abnormal returns and increases in risk. They also study the 1996 proposal by the Federal Reserve Board to increase the allowable Section 20 revenue to increase to 25% and find no wealth effects for commercial banks or investment banks. Bhargava and Fraser do not study the wealth effects of large banks expanding underwrit-ing power on smaller banks and only look at the initial proposal to increase the section 20 loophole.3

IV. Methodology and Data

Collectively, prior research indicates that commercial bank underwritten securities per-form better, or at least no worse than, investment bank underwritten securities. Thus, the role of informed monitor for banks, as well as the possible synergies with investment banks, apparently outweighs the potential conflicts of interest. Banks act as an “inside investor” because banks not only audit a firm but invest in the firm in the form of a loan, or as an equity underwriter. Other research based on simulations of mergers between investment and commercial banks indicates investment banking is more profitable, but higher risk and a lack of diversification offset the profitability.

This study is concerned with the market impact increased investment banking powers has on the banking industry, as well as groups of banks. That is, will banks benefit from the repeal of Glass–Steagall or from the widening of Section 20 loopholes? In addition, which group of commercial banks has potential competitive gains from increased invest-ment banking powers? This paper differs from other research in that the most recent approval of the increase in the loophole in 1996 is studied and includes interim announce-ments, and results are compared across groups of commercial banks.

The first hypothesis to test is whether or not the banking industry overall will benefit from investment banking activity. If commercial banks expand into investment banking via takeovers of existing investment banks, the takeover premium could be high, perhaps due to hubris as in Roll (1986) or an overestimation of scale and scope economies as in Trifts and Scanlon (1987).4If takeover premiums are sufficiently high on average, the market could have a negative reaction to the increased investment banking takeover or merger announcements. On the other hand, if private information, diversification, synergy, economies of scale, and other benefits outweigh the takeover and merger costs, stock price reaction should be positive on average to the announcement of increased investment banking powers. The results could also be insignificant if these effects offset.

3Bhargava and Fraser also study the wealth effect on investment banks. In this study, there are no significant

effects for any of the events for investment banks, thus the results are omitted in this paper.

4Note that many other studies find negative, insignificant, and positive CARs around bank takeover

As a corollary, it is hypothesized that banks have no changes in risk when entering underwriting activities. Kwast (1989) shows underwriting has higher returns and risk, and Gande, Puri, and Saunders (1999) indicate banks underwrite riskier lower rated and small debt as compared to investment banks. These prior results indicate a potential for a risk increase for commercial banks, which would be important for regulators and shareholders. However, if diversification benefits offset some of these risks, there could be insignificant or reductions in risk. Insignificant changes in risk were found by Apilado et al. (1993) around initial increased investment banking powers by commercial banks.

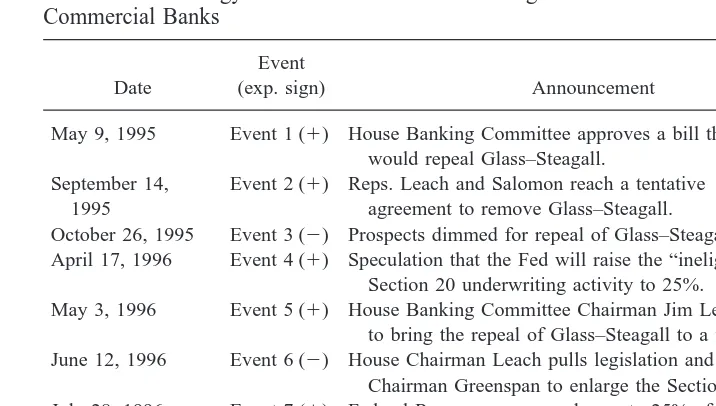

Table 1 shows relevant announcements concerning congressional discussion of the repeal of Glass–Steagall and of the subsequent Federal Reserve increase in Section 20 affiliate activity levels. If the repeal of Glass–Steagall is positive for commercial banks, then announcements favorable to the repeal of the Act or that indicate support for an increase in the Section 20 loophole will have positive stock price reactions on average.5 The expected signs are shown in Table 1, assuming that the ability of commercial banks to underwrite previously ineligible securities is valued by the market. The Goldman Sachs’ December 3, 1996 announcement on whether or not to buy a commercial bank has an uncertain stock price reaction. This event is included because it illustrates the com-petitive effects on commercial banks, absent any regulatory effects, of investment banks entering traditional banking activities. The announcement by Goldman Sachs’ is ambig-uous because it could mean more competition for traditional commercial banks (negative) or large takeover premiums for the target bank (positive). If either of these announcement effects offset, the result will be an insignificant stock price reaction.

The second hypothesis is that no group had a differential reaction to the increase in Section 20 activity. A differential reaction could indicate the market’s assessment of the

5The repeal of Glass–Steagall can be viewed as an increase in the Section 20 loophole to 100%.

Table 1. Chronology of Announcements Concerning Increased Investment Banking Powers for Commercial Banks

Date

Event

(exp. sign) Announcement Source

May 9, 1995 Event 1 (1) House Banking Committee approves a bill that would repeal Glass–Steagall.

NY Times

September 14, 1995

Event 2 (1) Reps. Leach and Salomon reach a tentative agreement to remove Glass–Steagall.

NY Times

October 26, 1995 Event 3 (2) Prospects dimmed for repeal of Glass–Steagall. NY Times

April 17, 1996 Event 4 (1) Speculation that the Fed will raise the “ineligible security” Section 20 underwriting activity to 25%.

WSJ

May 3, 1996 Event 5 (1) House Banking Committee Chairman Jim Leach tries to bring the repeal of Glass–Steagall to a floor vote.

WSJ

June 12, 1996 Event 6 (2) House Chairman Leach pulls legislation and asks Fed Chairman Greenspan to enlarge the Section 20 loophole.

WSJ

July 28, 1996 Event 7 (1) Federal Reserve proposes change to 25% of revenue for Section 20 affiliates.

WSJ

December 3, 1996 Event 8 (?) Goldman Sachs studies whether or not to buy a commercial bank.

WSJ

December 20, 1996 Event 9 (1) Rule change adopted to allow increase of affiliate ineligible revenue to 25%

WSJ

competitive effects of the ability to further expand investment banking activities. To test this hypothesis, the publicly traded commercial banks are split into four groups: (1) Money Center banks; (2) banks that already have Section 20 affiliates but are not Money Center banks; (3) Large Regional banks not in the prior groups; and (4) Small Regional banks not in the prior groups. Money center banks, with the exception of Wells Fargo, all have Section 20 subsidiaries before the time of study. However, Money Center banks perform currency trading, derivative trading, hedging activities, and other services at a much larger scale than most regional banks with Section 20 affiliates and would likely benefit more from scope economies in these areas. Apilado, Gallo, and Lockwood (1993) find that highly significant abnormal returns for Money Center banks for the 1987 Fed decision to allow Citicorp, J. P. Morgan, and Banker’s Trust to underwrite securities. The Money Center bank group is the same as Carow and Larsen (1997) with the Bank of New York replacing Chemical Bank after the Chase/Chemical merger. The Bank of New York is chosen because it is included in Salomon Brothers Money Center bank group and is often considered a Money Center bank [see Saunders (1994)]. Because of the differences in services and products, along with the more national scope of Money Center banks, banks with Section 20 subsidiaries that are not Money Centers are analyzed separately.6 Likewise, size is an important factor as indicated by Krosner and Rajan (1997) who found that prior to Glass–Steagall, banks actively engaged in underwriting through separate securities affiliates were larger than other commercial banks. The definitions of large and Small Regional banks are those banks with more or less than $10 billion in assets. Ten billion dollars is chosen because it is a relatively common demarcation point [e.g., see Carow and Larsen (1997)] and is used by the United States Banker. Also, it is likely that banks below $10 billion in asset size would not benefit from increasing investment banking.7

Money Center banks and those banks already with Section 20 subsidiaries are expected to have the highest probability of benefiting from increased investment banking powers because of prior access to the underwriting market. It is also hypothesized that Large Regional banks are most likely to benefit vis-a`-vis smaller regional banks because Large Regional banks can acquire larger investment banks and offer greater service to corporate customers.

To test the effects of the increase in investment banking powers for commercial banks, stock returns for all publicly traded banks on the Center for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP) tape for 1995 through 1996 are used. Returns are from 30 days before the first event to 10 days after the last event. Because the events surrounding the increasing of investment banking power are spread over 19 months, there are over 425 returns. Commercial banks with missing returns are deleted. Banks with contaminating events, such as becoming a takeover target, are removed from the sample. There are 98 publicly traded banks in the final sample. The appendix lists the banks, by group, as defined above.

6Banks with Section 20 subsidiaries are obtained from the Federal Reserve. My list differs from Gande, Puri,

and Saunders (1999) because many of the foreign bank ADRs have missing returns. I also include some banks with only Section 20 Tier I authority that cannot underwrite corporate equity since these banks are likely to be able to gain equity powers more easily. Results are virtually unchanged when Tier I banks are included or not as having Section 20 subsidiaries so I present the more general case here.

7Results for all tables that use the size categorization are qualitatively the same when the definition is

Because regulatory events are clustered in time, the appropriate methodology to test for abnormal performance is Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) as shown in Schipper and Thompson (1994), Binder (1985), Saunders and Smirlock (1987), Allen and Wilhelm (1988), Millon–Cornett and Tehranian (1990), or more recently Madura and Bartunek (1994), Wagster (1996), or Bhargava and Fraser (1998). SUR allows for heteroskedas-ticity across equations and contemporaneous dependence of the disturbances. The model used is as in Saunders and Smirlock (1987) and Bhargava and Fraser (1998) to study increased investment banking powers whereas accounting for possible non-synchronous trading.

The reaction to announcements affecting the increase in investment banking activity is measured through a series of multi-variable equations. Each equally weighted portfolio responds to the announcements through share price:

Rp5ap1b1pRm1b2pRm~t21!1

O

t51 9

AptDt1ep (1)

where Rpis the return on the equally weighted portfolio of bank stocks in portfolio p, from

one to four, Rm is the return on the equally weighted CRSP index, and Dtis a dummy

variable that equals one on the event day and the day before (days21 and 0) to account for information leakage and zero otherwise. The lagged market term is to account for non-synchronous trading as in Saunders and Smirlock (1987) and Bhargava and Fraser (1998).

Binder (1985) shows that SUR is equivalent to ordinary least squares (OLS) in testing for abnormal returns across all firms using Equation 1, except the dependent variable is an equally weighted portfolio of all commercial banks in the sample. In this context, the equation is discussed as if it is SUR to be consistent with the other results.

An industry-wide event such as increased investment banking power for commercial banks will likely change the risk characteristics of the commercial banks in anticipation of acquiring investment banks. As shown by Wall (1987) and Kwast (1989), investment banking activities are riskier than commercial banking where risk is measured as the SD of return on equity. Further, it is likely that banks with the highest probability of increasing investment bank activity will have the largest change in risk. To capture the potential increase in risk, Eq. (1) is modified to include risk-shift variables in the intercept, market return parameter, and non-synchronous trading parameter:

Rp5ap1a9pD11b1pRm1b2pRm~t21!1b91pD1Rm1b92pD1Rm~t21!

1

O

t51 9

AptDt1ep (2)

where D1is a dummy variable that is one after the dimming of prospects for repeal of

Glass–Steagall in October 1995.8The other variables are the same as in Equation 1 and the prime denotes a shift in the intercept, systematic risk, and non-synchronous trading sensitivities. This equation follows Saunders and Smirlock (1987) and Bhargava and Fraser (1998).

8A risk-shift after the speculation of the Fed (Event 4) was also evaluated with similar results, thus the results

Abnormal share price reactions or risk shifts for the four portfolios individually around announcements on event period t is tested under the null hypothesis of no abnormal returns or risk shifts. Also, the abnormal returns and risk shifts are tested for different reactions between groups under the null hypothesis of no differences between groups. SUR is a more powerful test of the hypothesis of no significant share price reactions across groups of banks and for differences among groups. The reason for using SUR is that events are clustered in time and that the change in regulation impacts the whole industry.

V. Empirical Results

To test for abnormal performance around the Fed announcement of increased investment banking powers for all banks, the coefficient for each dummy variable indicates the share price reaction to particular announcements. Thus, under the null hypothesis of no abnor-mal performance or risk shifts around the announcement of increased investment banking power, each variable should have an insignificant coefficient.

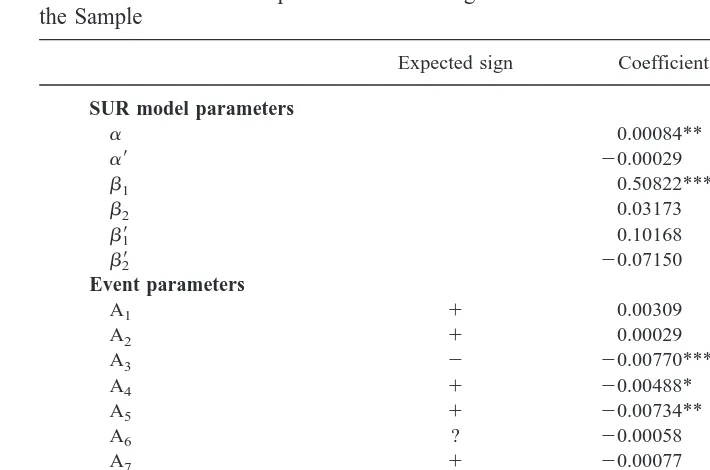

Table 2 contains results of the abnormal returns for all banks around the announce-ments of increased investment banking powers for commercial banks. As shown, the coefficient indicating prospects were reduced for passage of a repeal of Glass–Steagall (Event 3) is negative and significant as expected. Event 4 is negative and significant at the 10% level, counter to expectations. Because Event 4 is speculation of an increase in the Section 20 loophole, it is possible that market participants viewed this event as a sign that the bill would come to a vote more quickly and be defeated (e.g., a partial anticipation of Event 5). Event 5, the attempt by House Banking Committee Chairman Leach to bring the bill to repeal Glass–Steagall to a floor vote, is also negative, and significant at the 5% level. This is not the expected sign for this event, and could indicate that market participants were skeptical about the ability of the bill to pass Congress. Together, Events 4 and 5 indicate probable skepticism at repeal of Glass–Steagall.9The Section 20 loophole increase approval by the Federal Reserve (Event 9) is positive as expected and highly significant indicating all publicly traded banks are expected to gain from increased investment banking powers, on average. Bhargava and Fraser (1998) look only at the proposed increase in the section 20 loophole (Event 7); thus, one of the contributions of this study is to test all relevant announcements around this regulatory event. Note that these results for Event 7 confirm the findings of Bhargava and Fraser (1998) because there is an insignificant share price reaction, possibly due to skepticism about the Fed adopting the rule change.

As a corollary, the hypothesis of no risk change for all banks cannot be rejected as shown by the insignificant risk shift coefficients. This result supports the findings of Apilado et al. (1993) who also find no significant change in risk after prior increases in investment banking powers for commercial banks.

This paper also tests for abnormal returns for particular sub-groups of commercial banks around the announcements concerning the erosion of Glass–Steagall. Commercial

9Kroszner and Stratmann (1998) find Political Action Committee contributions to House Banking

banks that can benefit most from the advantages of underwriting issues should have higher stock returns upon announcement of increased investment banking activity. It is hypoth-esized that the banks most likely to benefit are Money Center banks and those previously with Section 20 affiliates. Super-regional banks are also likely to benefit if they can acquire investment banks, or start their own de novo affiliates. If being a Money Center bank or already holding a Section 20 subsidiary is more important than the possibility of initial entry into investment banking, there should be a significant difference between Money Center and Section 20 banks versus Large Regional banks as well. That is, if it is more valuable to increase current Section 20 underwriting business than start or acquire a subsidiary, stock price gains will be lower to banks that merely have an increased chance to enter the activity.

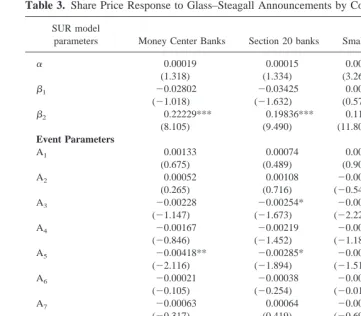

Table 3 shows the results from the SUR model by group from Eq. (1). This model accounts for the event-clustering and cross correlations among all publicly traded com-mercial banks. When prospects dimmed for Glass–Steagall (Event 3), all bank groups had negative CARs, but only the small bank group was significant at the 5% level with large banks and Section 20 banks significant at the 10% level. All groups, except the small bank Table 2. Share Price Response to Glass–Steagall Announcements for All Commercial Banks in the Sample

*5significant at the 10% level. **5significant at the 5% level. ***5significant at the 1% level.

The model is: Rp5ap1a9D11b1pRm1b2Rm(t21)1b91D1Rm1b92D1Rm(t21)1¥t51 9 A

ptDt1ep

where Rpis the return on the portfolio of all commercial banks, Rmis the return on the equally weighted CRSP index, the lagged

market return is included to account for nonsynchronous trading, D1is a risk-shift dummy, and Dtis the event dummy. The prime

group, have negative and significant abnormal returns around the attempt by Chairman Leach to bring the bill to repeal Glass–Steagall to a floor vote (Event 5), although Section 20 and Large Regionals are significant at only the 10% level. Thus, it seems that market participants viewed a lower probability of repeal for Glass–Steagall as negative only if the bank was of sufficient size. Similarly, small banks are the only group not to have a significantly negative reaction to the Goldman Sachs announcement of intent to purchase a commercial bank. Apparently market participants expect large investment houses to compete more directly with Money Center, bank affiliated underwriters, and Large Regional banks for commercial business. All groups of banks, except small banks, experience a positive and significant reaction to increased investment banking powers Table 3. Share Price Response to Glass–Steagall Announcements by Commercial Bank Group

SUR model

parameters Money Center Banks Section 20 banks Small banks Large banks

a 0.00019 0.00015 0.00017*** 0.00013

(1.318) (1.334) (3.264) (1.464)

b1 20.02802 20.03425 0.00551 20.00242

(21.018) (21.632) (0.571) (20.149)

b2 0.22229*** 0.19836*** 0.11357*** 0.17121***

(8.105) (9.490) (11.801) (10.602)

Event Parameters

A1 0.00133 0.00074 0.00063 0.00134

(0.675) (0.489) (0.902) (1.148)

A2 0.00052 0.00108 20.00038 0.00049

(0.265) (0.716) (20.545) (0.420) A3 20.00228 20.00254* 20.00155** 20.00195*

(21.147) (21.673) (22.224) (21.665) A4 20.00167 20.00219 20.00082 20.00150

(20.846) (21.452) (21.182) (21.289) A5 20.00418** 20.00285* 20.00105 20.00224*

(22.116) (21.894) (21.518) (21.920) A6 20.00021 20.00038 20.00001 20.00047

(20.105) (20.254) (20.015) (20.404)

A7 20.00063 0.00064 20.00048 20.00007

(20.317) (0.419) (20.691) (20.060) A8 20.00400** 20.00298** 0.00034 20.00216*

(22.025) (21.977) (0.494) (21.857)

A9 0.00453** 0.00498*** 0.00113 0.00381***

(2.287) (3.300) (1.632) (3.265)

Statistics

Number of banks 8 25 52 13

F-Value 8.009*** 11.120*** 15.838*** 13.788***

*5significant at the 10% level. **5significant at the 5% level. ***5significant at the 1% level.

The model is: Rp5ap1b1pRm1b2pRm(t21)1¥t51 9 A

ptDt1ep

where Rpis the return on the group portfolio, Rmis the return on the equally weighted CRSP index, the lagged market return

is included to account for nonsynchronous trading, and Dtis the event dummy. Event 1 is House approval of a bill to repeal

when the Federal Reserve increased the Section 20 loophole (Event 9), with Section 20 banks and large banks significant at the 1% level.

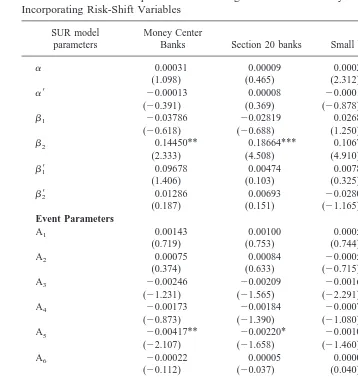

Table 4 shows the results from the SUR model by group from Eq. (2). The model from Eq. (2) captures a risk shift after Event 3, which is the first significant event for the entire group of banks (see Table 3). The risk shift coefficients are mostly insignificant and Table 4. Share Price Response to Glass–Steagall Announcements by Commercial Bank Group Incorporating Risk-Shift Variables

SUR model parameters

Money Center

Banks Section 20 banks Small banks Large banks

a 0.00031 0.00009 0.00023** 0.00011

(1.098) (0.465) (2.312) (0.664)

a9 20.00013 0.00008 20.00010 0.00001

(20.391) (0.369) (20.878) (0.067)

b1 20.03786 20.02819 0.02688 0.02308

(20.618) (20.688) (1.250) (0.639)

b2 0.14450** 0.18664*** 0.10671*** 0.15419***

(2.333) (4.508) (4.910) (4.226)

b91 0.09678 0.00474 0.00784 0.02107

(1.406) (0.103) (0.325) (0.520)

b92 0.01286 0.00693 20.02807 20.03211

(0.187) (0.151) (21.165) (20.794)

Event Parameters

A1 0.00143 0.00100 0.00052 0.00132

(0.719) (0.753) (0.744) (1.129)

A2 0.00075 0.00084 20.00050 0.00047

(0.374) (0.633) (20.715) (0.400) A3 20.00246 20.00209 20.00161** 20.00200*

(21.231) (21.565) (22.291) (21.697) A4 20.00173 20.00184 20.00075 20.00148

(20.873) (21.390) (21.080) (21.264) A5 20.00417** 20.00220* 20.00101 20.00223*

(22.107) (21.658) (21.460) (21.913)

A6 20.00022 0.00005 0.00003 20.00047

(20.112) (20.037) (0.040) (20.404)

A7 20.00070 0.00018 20.00038 0.00002

(20.352) (0.131) (20.546) (20.013) A8 20.00403** 20.00282** 0.00040 20.00215*

(22.032) (22.129) (0.572) (21.840)

A9 0.00445** 0.00437*** 0.00120* 0.00383***

(2.243) (3.297) (1.729) (3.275)

where Rpis the return on the group portfolio, Rmis the return on the equally weighted CRSP index, the lagged market return

is included to account for nonsynchronous trading, D1is a risk-shift dummy, and Dtis the event dummy. The prime denotes a

positive. Because all the risk variables are positive, this suggests that risk has slightly increased after the possibility of investment banking for commercial banks, perhaps due to greater risk of investment banks. Of course this result is tenuous at best given the insignifi-cance of this variable. The risk shift results support the findings of Apilado et al. (1993).

Results in Table 4 are very similar to the non-risk-shift results. Small banks have significantly negative abnormal returns when prospects dimmed for Glass–Steagall (Event 3), with large banks negative and significant at the 10% level. When Chairman Leach attempts to bring the bill to repeal Glass–Steagall to a floor vote (Event 5), all groups except small banks have negative announcement abnormal returns as is the case in the other model. Money Center and Section 20 banks have a significant at the 5% level and negative reaction to the Goldman Sachs announcement of intent to purchase a commercial bank (Event 8). Large banks also have a negative reaction to Event 8, except it is significant at only the 10% level. When the Federal Reserve increased the Section 20 loophole (Event 9), all groups have a significant and positive reaction, except Small Regional banks that have a positive reaction significant at only the 10% level.10

Because Small Regional banks have less significant reactions to increased investment banking powers, these findings suggest that asset size is important in the ability to capitalize on investment banking. A direct test of the corollary to hypothesis 2 for differences in the event period market reaction among the matched pairs of all groups was performed using an F-test (not shown here). The F-test indicates that Money Center, Section 20, and Large Regional banks have statistically significant differences in market reactions as compared to Small Regional banks to increased Section 20 investment banking powers (Event 9) using both models from Eqs. (1 and 2).11The difference for Event 9 CARs is over 26 basis points for all groups and as much as 32 basis points versus the Small Regional bank portfolio abnormal returns. This suggests the only difference among stock price reactions to announcements of increased investment banking powers by commercial banks is due to having large enough size to enter investment banking activity. This conjecture will be tested more directly in the cross sectional model below where other variables, such as capital, are explicitly considered.

VI. Cross Sectional Analysis

Given the findings of differential share price reaction among groups, a natural question is what makes these groups react differently? It is hypothesized that differential performance among banks around the announcements of increased investment banking is a function of being a Money Center bank, having prior Section 20 subsidiaries, and bank characteristics such as size, capital, and bank balance sheet composition. Banks with higher capital could also benefit because allowance of investment banking activity is contingent on regulatory approval and regulators consider capital very important. It is also likely that banks with the lowest performance stand to gain the most from investment banking activity. Of course if poor performance is indicative of poor management, low prior performance could indicate lower announcement abnormal returns.

10Results are very similar using value-weighted portfolios. The only exceptions are that small banks show

significance at the ten-percent level for event nine in Table 3; Section 20 banks show significance at the 10% level for Event 3, and Event 3 becomes highly significant for small banks in Table 4.

11Similar to the F-test in Tables 3 and 4, an alternate specification (not shown) is the SUR model on a

Cross sectional analysis of the abnormal returns from the event study is used to test for differential performance around announcements of investment banking powers for com-mercial banks. The cross sectional model is:

CARi,t5v 1 l1MONEYCTR1l2SEC20SUB1l3LARGE1l4SMALL

1l5CAPRATIO1l6LNRATIO1l7ROA1l8DEPRATIO1l9NONTOINT

1l10TRADASST1ji,t (3)

where MONEYCTR is a dummy variable that equals one if a Money Center bank and zero otherwise; SEC20SUB is a dummy variable if the commercial bank has a prior Section 20 subsidiary and is not a Money Center bank, and zero otherwise; LARGE is a dummy variable that equals one if the bank has average assets larger than $10 billion and is not in the other groups, SMALL is a dummy equal to one if the bank has average assets less than $10 billion and is not in the other groups and zero otherwise; CAPRATIO is the average capital to assets ratio; LNRATIO is the average loan to asset ratio; ROA is the average return on assets; DEPRATIO is the average deposit to asset ratio; NONTOINT is average non-interest income to total interest income, and TRADASST is the notional value of trading assets to total assets.12The dependent variable is the individual bank abnormal return from Eq. (1 or 2) for Event 9 because this event is the only one with consistently significant share price reactions.13

These cross sectional variables include capital, risk as proxied by loans to assets, performance as proxied by ROA, and proportion of banking activity as proxied by deposits to assets. The ratios of non-interest income to total income and notional trading value to total asset value are used as a proxy for off-balance sheet activity and derivative activity. All of the cross sectional variables come from the Call and Income reports and are a 5-year average (1992–1996) for each of these variables to eliminate excessive variation. Bank variables are aggregated at the holding company level where appropriate. Banks missing more than 1 year of cross sectional data are deleted from the cross sectional analysis. There are 70 banks that have sufficient data for cross sectional analysis.

Expectations are that Money Center banks and those with prior Section 20 subsidiaries have higher announcement period abnormal returns, ceteris paribus, thus the coefficients for MONEYCTR and SEC20SUB are expected to be positive and significant. Large and well-capitalized banks are expected to benefit more from increased investment banking powers, thus the expected signs for LARGE and CAPRATIO are expected to be positive. The loan to asset and deposit to asset ratios are used to proxy for traditional banking activities. For those banks that are in relatively unsaturated banking markets, the benefit from increased investment banking activity is expected to be less. Thus, the expectation for the coefficients on LNRATIO and DEPRATIO is positive indicating banks that have high percentages of traditional banking activities gain more from the erosion of Glass– Steagall. Prior performance, as indicated by return on assets, could have a positive effect if the market views the high performance as more likely to be allowed to enter investment

12A continuous size variable (log of assets) was also used, but had to be dropped from the regressions due

to severe multicollinearity with most of the other independent variables.

13I also use Event 8 abnormal returns and find similar results, but with the opposite sign since the

competition from Goldman Sachs is more likely to harm large commercial banks than small commercial banks. For both events 8 and 9 together, the adjusted R2is negative and the model is insignificant, so results are not

banking by regulators, or as an indication of good management. However, if banks with high ROA gain the least in performance terms from entering investment banking, the coefficient for

ROA will be negative. If there are economies of scale and scope with off-balance-sheet and

derivatives activities, the coefficients for NONTOINT and TRADASST will be positive. The intercept in the cross sectional regressions is constrained as in Suits (1984) and Kennedy (1986) where the group dummies are compared to the weighted-average bank in the sample. If all groups were included with an intercept, perfect multicollinearity would result. Because this paper is concerned with winners and losers across groups, this method is used to allow a comparison of all groups in a single model instead of omitting one group and have all other groups compared to that base. Thus, a positive and significant group dummy indicates that that particular group of banks had a higher stock price reaction than the average bank in this sample.

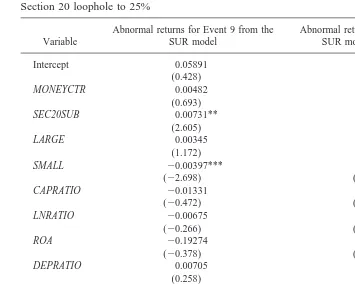

Table 5 shows the results of the cross sectional regression for Event 9 abnormal returns from both the models with and without a risk-shift variable. The indicator variable for Section 20 banks is positive and significant for both models. This indicates that banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries are expected to gain more than the average bank, at least in this sample of publicly traded banks. The Small Regional bank group has a negative and significant coefficient indicating a significantly lower stock price reaction than the average bank in the sample. The cross sectional regressions show that the abnormal returns are a function of prior Section 20 activity, and not being too small to participate in investment banking in a meaningful way and not other bank characteristics. It seems that market participants expect those banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries to gain from increased investment banking power vis-a´-vis Small Regional banks that lose as compared to the average bank. In addition, the results hold when explicitly considering capital, balance sheet characteristics, and prior performance, which are all insignificant in the cross sectional regressions. Likewise, the coefficients for derivative and off-balance-sheet activity are positive, but insignificant. The cross sectional findings support the results in Tables 3 and 4 and suggest that size is the most important factor in the ability to benefit from increased investment banking powers for commercial banks.14

VII. Summary and Conclusions

This paper studies the effects of increased investment banking powers in the commercial banking industry. Section 20 of the Glass–Steagall Act, as amended on December 20, 1996, allows commercial bank affiliates to underwrite up to 25% of revenue in previously ineligible securities of corporate equity or debt. Share price effects to announcements concerning the repeal of Glass–Steagall and the increase in the Section 20 loophole from 10% to 25% of affiliate activity are studied in a SUR model.

For all commercial banks collectively in the sample, the effect of reduced prospects for the repeal of Glass–Steagall is negative and significant. The share price reaction to speculation of an increase in the loophole and Chairman Leach trying to bring the bill to repeal Glass–Steagall to a floor vote is also negative and significant for all commercial banks. Abnormal returns for all commercial banks are positive and significant when the Federal Reserve approved the increase in the Section 20 loophole to 25%. These findings

14Note that when using the “traditional” method of omitting one group, the small bank group had negative

suggest that market participants value increased investment banking powers for commer-cial banks, but they were skeptical of passage of a bill to repeal Glass–Steagall in Congress.

The banks are then split into four groups: 1) Money Center banks, 2) banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries that are not Money Center banks, 3) Large Regional banks defined as those with assets larger than $10 billion, and 4) Small Regional banks defined as those with less than $10 billion in assets. The SUR results for each group show that only Small Regional banks had negative abnormal returns significant at the 5% level when prospects for passage of Glass–Steagall were reduced. All banks except Small Regional banks reacted negatively to the attempt of a floor vote for the repeal of Glass–Steagall, although Table 5. Cross sectional regressions of CARs from the enlargement of the Glass–Steagall Section 20 loophole to 25%

Variable

Abnormal returns for Event 9 from the SUR model

Abnormal returns for Event 9 from the SUR model with a risk-shift

**5significant at the 5% level. ***5significant at the 1% level. The model is:

CARi,t5v1l1MONEYCTR1l2SEC20SUB1l3LARGE1l4SMALL1l5CAPRATIO1l6LNRATIO1l7ROA1

l8DEPRATIO1l9NONTOINT1l10TRADASST1ji,t

where the dependent variable is the individual bank abnormal return for the enlargement of the Section 20 loophole to 25% as measured by the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) coefficient. For independent variables, MONEYCTR is an indicator variable that equals one for a Money Center bank and zero otherwise; SEC20SUB is a dummy variable that equals one if the bank has a Section 20 affiliate before the increased loophole and is not a Money Center bank and equals zero otherwise; LARGE is a dummy variable that equals one if the bank is larger than $10 billion in average assets and not a Money Center or Section 20 bank and zero otherwise; SMALL is a dummy variable that equals one if the bank is smaller than $10 billion in average assets and not in the other categories; ROA is the bank’s return on assets; DEPRATIO is the deposit to asset ratio for the bank; and

LNRATIO is the bank’s loan to asset ratio; NONTOINT is the banks non-interest income to total interest income ratio; TRADASST

Section 20 and Large Regionals were significant at only the 10% level. All banks except Small Regionals have a negative reaction to the Goldman Sachs announcement to buy a commercial bank, significant at least the 10% level. All banks except Small Regional banks have a positive and significant the reaction to increased Section 20 investment banking powers, although the Small Regional group is significant at the 10% level in the model that incorporates risk shifts. These results hold for a model that incorporates a risk-shift and nonsynchronous trading variable.

Because F-tests suggest significantly different reactions between Small Regional banks and all three other groups, a cross sectional analysis is performed for the reaction to the Federal Reserve increasing Section 20 powers on December 20, 1996. The abnormal returns are positive and highly significant for banks with prior Section 20 subsidiaries and negative and significantly lower for Small Regional banks as compared to the average bank in the sample. Money Center status, prior performance, loans to assets, deposits to assets, capital, off-balance sheet, and derivative trading variables are all found to be insignificant in the cross sectional models. The results hold in models that incorporate a risk-shift variable or not.

The cross sectional findings indicate that the ability to gain from investment banking activity is a function of large enough size to be able to adequately acquire an investment bank to augment the commercial banking product line, and more importantly prior Section 20 activity. Small Regional banks are not likely to be able to acquire underwriters that are large enough to service the commercial customers that require investment banking services. The gains in one-stop commercial and investment banking along with potential synergies and economies of scope are apparently outweighing the large merger premia and the potential conflicts of interest that are likely to be required to enter into the new era of financial services.

These results support the findings of Ang and Richardson (1996), Kroszner and Rajan (1994), and Puri (1996) that the potential conflicts of interest between commercial and investment banking are not too severe. The results confirm the findings of Bhargava and Fraser (1998) who find no reaction around the initial announcement by the Fed to increase the loophole. However, this paper studies the events before and after the Fed announce-ment to capture the full effect of increased investannounce-ment banking power as well as comparing the reaction of other publicly traded banks to study potential competitive effects. One of the main contributions of this paper is to show that the true event for increasing the Section 20 loophole was the final approval and not the initial proposal to increase the loophole as in Bhargava and Fraser (1998).

Although an argument can be made that large commercial banks are expected to gain vis-a`-vis small commercial banks, these findings suggest the demise of Glass–Steagall is positive overall for the commercial banking industry. Market participants indicate that the ability to increase corporate debt and equity underwriting is more valuable given large enough size to enter the activity. Smaller banks that are unable to capitalize on the increased investment banking activity could be at a competitive disadvantage in the long-run if market participants are correct in their assessment of the impact of increased investment activity by commercial banks.

Appendix I

Firms Used in the Study, by GroupMoney Center Banks

Bank New York Inc. Citicorp

BankAmerica Corp. Morgan J P & Co. Inc. Bankers Trust NY Corp. NationsBank Corp. Chase Manhattan Corp. New Wells Fargo & Co. New

Banks with Prior Section 20 Subsidiaries or Approval

Banc One Corp. Keycorp New

Banco Santander SA Mellon Bank Corp. Bank Of Boston Corp. National City Corp.

Bank of Montreal National Westminster Bank PLC Barclays Bank PLC Norwest Corp.

Barnett Banks Inc. P N C Bank Corp. Crestar Financial Corp. Republic New York Corp. Dauphin Deposit Corp. Royal Bank of Canada First Chicago N B D Corp. Southtrust Corp. First of America Bank Corp. Suntrust Banks Inc. First Union Corp. Synovous Financial Corp. Fleet Financial Group Inc. Toronto Dominion Bank Huntington Bancshares Inc.

Small Regional Banks (Average Assets Of Less Than $10 Billion)

1st Source Corp. Jefferson Bankshares Inc. Amcore Financial Inc. Keystone Financial Inc. Associated Banc Corp. Keystone Heritage Group Inc. Bancorp Hawaii Inc. Magna Group Inc.

Central Fidelity Banks Inc. Mercantile Bankshares Corp. Chittenden Corp. National Bancorp AK Citizens Banking Corp. MI National City Bancorporation Colonial Bancgroup Inc. National Penn Bancshares Commerce Bancshares Inc. North Fork BanCorp NY Inc. Compass Bancshares Inc. One Valley Bancorp Inc. Cullen Frost Bankers Inc. Peoples Heritage Finl. Group Deposit Guaranty Corp. Provident Bancorp Inc.

F N B Corp. PA Republic Bancorp

F N B Rochester Corp. Riggs National Corp. Wash. First Bank System Inc. Simmons 1st National Corp. First Banks America Inc. Southern National Corp. NC First Commerce Corp. New Orleans Sterling Bancorp

First Hawaiian Inc. Summit Bancorp

First Midwest Bancorp DE Susquehanna Bancshares Inc. First Virginia Banks Inc. U M B Financial Corp. FirstMerit Corp. United Bankshares Inc. Fulton Financial Corp. PA United States Bancorp

H U B C O Inc. Usbancorp Inc. PA

Imperial Bancorp WestAmerica Bancorporation Irwin Financial Corp. Zions Bancorp

Large Regional Banks (Average Assets Of Greater Than $10 Billion)

Amsouth Bancorporation Marshall & Ilsley Corp. Comerica Inc. Mercantile Bancorporation Corestates Financial Corp. Northern Trust Corp. Fifth Third Bancorp Old Kent Financial Corp. First Empire State Corp. Regions Financial Corp. First Tennessee National Corp. Union Planters Corp.

References

Allen, P. R., and Wilhelm, W. J. 1988. The impact of the 1980 Depository Deregulation and Monetary Control Act on market value and risk: Evidence from the capital markets. Journal of

Money, Credit, and Banking 20:364–380.

Ang, J., and Richardson, T. 1994. The underwriting experiences of commercial bank affiliates prior to the Glass–Steagall Act: A re-examination of evidence for passage of the Act. Journal of

Banking and Finance 18:351–395.

Apilado, V. P., Gallo, J. G., and Lockwood, L. J. 1993. Expanded securities underwriting: Implications for bank risk and return. Journal of Economics and Business 45:143–158. Benston, G. J. 1994. Universal banking. Journal of Economic Perspectives 8:121–143.

Bhargava, R. and Fraser, D. R. 1998. On the wealth and risk effects of commercial bank expansion into securities underwriting: An analysis of Section 20 subsidiaries. Journal of Banking and

Finance 22:447–465.

Binder, J. J. 1985. On the use of multivariate regression model in event studies. Journal of

Accounting Research 23:370–383.

Boyd, J. H., Graham, S. L., and Hewitt, R. S. 1993. Bank holding company mergers with nonbank financial firms: Effects on the risk of failure. Journal of Banking and Finance 17:43–63. Carow, K. A., and Larsen, G. A. Jr. 1997. The effect of FDICIA regulation on bank holding

companies. The Journal of Financial Research 20:159–174.

Gande, A., Puri, M., Saunders, A., and Walter, I. 1997. Bank underwriting of debt securities: Modern evidence. Review of Financial Studies 10:1175–1202.

Gande, A., Puri, M., and Saunders, A. 1999. Bank entry, competition and the market for corporate securities underwriting. Journal of Financial Economics, In press.

Gompers, P., and Lerner, J. 1999. Conflict of interest in the issuance of public securities: Evidence from venture capital. Journal of Law and Economics 42:1–28.

Hamoa, Y. and Hoshi, T. 1997. Banks underwriting of corporate bonds: Evidence from Japan after 1994. Working Paper University of Southern California.

Hamoa, Y., Packer, P. and Ritter, J. 1998. Institutional affiliation and the role of venture capital: Evidence from initial public offerings in Japan. Working Paper University of Florida. Kanatas, G., and Qi, J. 1998. Underwriting by commercial banks: Incentive conflicts, scope

economies, and project quality. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 30:119–133.

Kennedy, P. E. 1986. Interpreting dummy variables. The Review of Economics and Statistics 68:174–175.

Kroszner, R., and Rajan, R. 1994. Is the Glass–Steagall Act justified? A study of the U.S. experience with universal banking before 1933. American Economic Review 84:810–832.

Kroszner, R., and Rajan, R. 1997. Organization structure and credibility: Evidence from commercial bank securities activities before the Glass–Steagall Act, Journal of Monetary Economics 39: 475–516.

Kroszner, R., and Stratmann, T. 1998. Interest-group competition and the organization of congress: Theory and evidence from the financial services’ political action committees. American

Eco-nomic Review 88:1163–1187.

Kwast, M. L. 1989. The impact of underwriting and dealing on bank returns and risks. Journal of

Banking and Finance 13:101–126.

Madura, J., and Bartunek, K. 1994. Contagion effects of the bank of New England’s failure. Review

of Financial Economics 4:25–37.

Mester, L. 1997. Repealing Glass–Steagall: The past points the way to the future. Federal Reserve

Business Review 1:1–10.

Millon–Cornett, M., and Tehranian, H. 1990. An examination of the impact of the Garn–St Germain Depository Institutions Act on 1982 on commercial banks and savings and loans. The Journal of

Puri, M. 1994. The long-term default performance of bank underwritten security issues. Journal of

Banking and Finance 18:397–418.

Puri, M. 1996. Commercial banks in investment banking conflict of interest or certification role?,

Journal of Financial Economics 40:373–401.

Puri, M. 1999. Commercial banks as underwriters: Implications for the going public process.

Journal of Financial Economics 54:133–163.

Rajan, R. G. 1998. An investigation into the economics of extending bank power. Working Paper

University of Chicago.

Rhoades, S. A. 1994. A summary of merger performance studies in banking 1980–93, and an assessment of the ‘operating performance’ and ‘event study’ methodologies. Federal Reserve

Board of Governors Staff Study 169.

Roll, R. 1986. The Hubris hypothesis of corporate takeovers. Journal of Business 59:197–216. Saunders, A. 1985. Conflicts of interest: An economic view. In Deregulating Wall Street. (I. Walter,

Ed.). New York: John Riley and Sons, 207–230.

Saunders, A. 1994. Financial institutions management: A modern perspective (Richard D. Irwin, Burr Ridge, IL).

Saunders, A., and Smirlock, M. 1987. Intra- and interindustry effects of bank securities market activities: The case of discount brokerage. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 22:467–482.

Schipper, K., and Thompson, R. 1983. The impact of merger-related regulations on the shareholders of acquiring firms. Journal of Accounting Research 21:184–221.

Suits, D. B. 1984. Dummy variables: Mechanics v. interpretation. The Review of Economics and

Statistics 66:143–145.

Trifts, J. W., and Scanlon, K. P. 1987. Interstate bank mergers: The early evidence. Journal of

Financial Research 10:305–312.

Wagster, J. D. 1996. Impact of the 1988 Basle accord on international banks. The Journal of Finance 51:1321–1346.

Wall, L. D. 1987. Has bank holding companies’ diversification affected their risk of failure?.